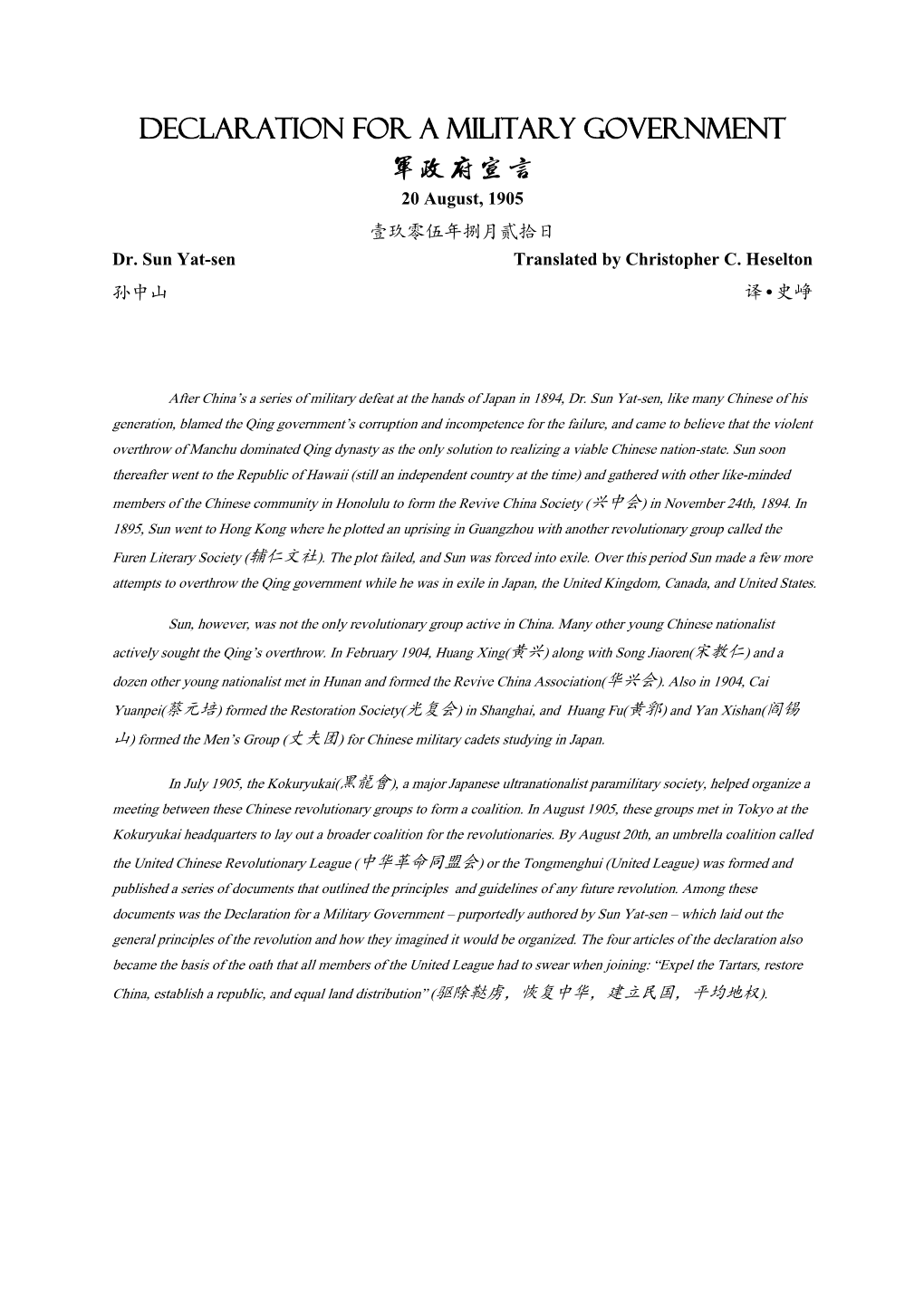

Declaration for a Military Government 军政府宣言 20 August, 1905 壹玖零伍年捌月贰拾日 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Appraisal

Serial No.: N24 Historic Building Appraisal Pak Tsz Lane, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong Located in the bustling Central district, Pak (Tsz Lane 百子里) can Historical arguably be considered to be a cradle for the 1911 Chinese Revolution under Interest th the leadership of Dr. Sun Yat-sen (Sun Yixian, 孫逸仙). During the late 19 and early 20th centuries, it was a meeting place for the Chinese revolutionaries notably Tse Tsan-tai (Xie Zantai, 謝纘泰) and Yeung Ku-wan (Yang Quyun, 楊衢雲 ) for discussion of political affairs and plotting rebellions that eventually led to the downfall of the Qing dynasty. Yeung Ku-wan (楊衢雲) founded Foo Yan Man Ser (Furen wenshe, 輔仁 文社, “Literary Society for the Promotion of Benevolence”) (the Society) in the premises of No. 1 Pak Tsz Lane on 13 March 1892, and the Society’s motto was “Ducit Amor Patriae” (in English: “Love of country leads [me]”). The sixteen members of the Society , who always held meetings in private to discuss political issues and the future of China, had all been educated in Hong Kong and most of them were employed as teachers or clerks in government offices or shipping companies. Several of these men joined Hsing Chung Hui (Xingzhonghui, 興中會, “Revive China Society ”) when it was founded in 1895, and Yeung was the President of the Hong Kong bra nch of Hsing Chung Hui. Yeung Ku-wan was shot dead in his residence in No. 52 Gage Street, at the end of Pak Tsz Lane. The murder took place in the evening of 10 January 1901, when he was holding his English class for boys. -

The Chinese Civil War (1927–37 and 1946–49)

13 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 2: THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR (1927–37 AND 1946–49) As you read this chapter you need to focus on the following essay questions: • Analyze the causes of the Chinese Civil War. • To what extent was the communist victory in China due to the use of guerrilla warfare? • In what ways was the Chinese Civil War a revolutionary war? For the first half of the 20th century, China faced political chaos. Following a revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Manchu dynasty, the new Republic failed to take hold and China continued to be exploited by foreign powers, lacking any strong central government. The Chinese Civil War was an attempt by two ideologically opposed forces – the nationalists and the communists – to see who would ultimately be able to restore order and regain central control over China. The struggle between these two forces, which officially started in 1927, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, but started again in 1946 once the war with Japan was over. The results of this war were to have a major effect not just on China itself, but also on the international stage. Mao Zedong, the communist Timeline of events – 1911–27 victor of the Chinese Civil War. 1911 Double Tenth Revolution and establishment of the Chinese Republic 1912 Dr Sun Yixian becomes Provisional President of the Republic. Guomindang (GMD) formed and wins majority in parliament. Sun resigns and Yuan Shikai declared provisional president 1915 Japan’s Twenty-One Demands. Yuan attempts to become Emperor 1916 Yuan dies/warlord era begins 1917 Sun attempts to set up republic in Guangzhou. -

Notes and References

Notes and References Front and Introduction 1. Hu Yaobang's interview with Selig Harrison, Far Eastern Economic Review, 26 July 1986. 2. Ma Ying-cheou's interview with the author, Taipei, June 1989. 1 Geography and Early History On Taiwan's topography, see Anon. (1960) and Hseih (1964). On pre-history, see Chai (1967), Davidson (1988) and God dard (1966). Early contacts with the mainland Davidson (1988), Goddard (1966) and Reischauer and Fair bank (1958). Early foreign contacts Davidson (1988), Goddard (1966), Hsu (1970) and Reischauer and Fairbank (1958). Taiwan under the Dutch Campbell (1903), Davidson (1988) and Goddard (1966). The Koxinga interregnum Croizier (1977), Hsu (1970) and Kessler (1976). The 'Wild East' Davidson (1988), Goddard (1966) and Gold (1986). Taiwan joins international politics Broomhall (1982), Davidson (1988), Hibbert (1970), Hsu (1970), Wang and Hao (1980) and Yen (1965). Early modernisation Goddard (1966), Gold (1986) and Kerr (1974). 246 Notes 247 The Japanese annexation Davidson (1988), Hsu (1970), Jansen (1980), Kerr (1974), Li (1956), Reischauer and Fairbank (1958), Smith and Liu (1980) and Wang and Hao (1980). Taiwan under the Japanese Behr (1989), Davidson (1988), Gold (1986), Ho (1978), Kerr (1974) and Mendel (1970). REFERENCES l. The 'Dragon Myth' is cited in Davidson (1988). 2. Quoted in Campbell (1903). 3. Quoted in Hsu (1970). 4. Quoted in Gold (1986). 5. Quoted in Davidson (1988). 6. Fairbank (1972). 2 The Kuomintang The Kuomintang in 1945 Belden (1973), Bianco (1971), China White Paper (1967), Harrison (1976), Kerr (1974), Loh (1965), Seagrave (1985) and Tuchman (1972). Sun Yat-sen and the origins of the KMT Bianco (1971), Chan (1976), Creel (1953), Fairbank (1987), Gold (1986), Harrison (1976), Hsu (1970), Isaacs (1951), Schiffrin (1968), Spence (1982) and Tan (1971). -

Beyond Life and Death Images of Exceptional Women and Chinese Modernity Wei Hu University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Beyond Life And Death Images Of Exceptional Women And Chinese Modernity Wei Hu University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hu, W.(2017). Beyond Life And Death Images Of Exceptional Women And Chinese Modernity. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4370 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND LIFE AND DEATH IMAGES OF EXCEPTIONAL WOMEN AND CHINESE MODERNITY by Wei Hu Bachelor of Arts Beijing Language and Culture University, 2002 Master of Laws Beijing Language and Culture University, 2005 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Michael Gibbs Hill, Major Professor Alexander Jamieson Beecroft, Committee Member Krista Jane Van Fleit, Committee Member Amanda S. Wangwright, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Wei Hu, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To My parents, Hu Quanlin and Liu Meilian iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During my graduate studies at the University of South Carolina and the preparation of my dissertation, I have received enormous help from many people. The list below is far from being complete. First of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my academic advisor, Dr. -

Role of Min Bao in Creating Public Opinion for the Revolution of 1911

2018 3rd International Social Sciences and Education Conference (ISSEC 2018) Role of Min Bao in Creating Public Opinion for the Revolution of 1911 Zhang Yongxia School of Arts and Law, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 430070 Keywords: Min Bao; The Revolution of 1911; creation of public opinion Abstract: As an official organ of Tongmenghui, Min Bao played an important role in creating public opinion for the revolution of 1911. This paper expounds the historical background at that time and how Min Bao created public opinion, and then clarifies why this magazine has had such a wide influence. Through introducing revolution situations and social ideological trends in foreign countries and infusing revolutionary thoughts into the readers, Min Bao inspired revolutionaries to fight for the revolutionary ambitions with the spirit of sacrifice and striving, thus helping them to shape their life value outlooks, form their revolutionary convictions and develop their revolutionary behavior patterns. 1. Introduction The Revolution of 1911 was a milestone in China's history. In reviewing the course of the Revolution of 1911, Sun Yat-sen spoke highly of the role of bourgeois revolutionary newspapers and magazines in promoting the revolutionary cause [1]. The bourgeois revolutionist Feng Ziyou once said, "The foundation of Republic of China should be attributed to the military actions and the propaganda by the Chinese Revolutionary Party, between which the propaganda was more powerful and widely-influenced." Among various bourgeois revolutionary newspapers and magazines, Min Bao played a great role in promoting the dissemination of bourgeois democratic revolutionary thoughts, eliminating the reformers' pernicious influence, of the reformists, facilitating the formation of the revolutionary spirit, and improving the revolutionary situation. -

China's 1911 Revolution

www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview Volume 23, Number 1, September 2020 Revision China’s 1911 Revolution Nicholas Fellows Test your knowledge of the 1911 Revolution in China and the events preceding it with these multiple-choice questions. Answers on the final page Questions 1 When did the First Opium War start? 1837 1838 1839 1840 2 What term was used to describe the agreements China was forced to sign with the West following its defeat? Unfair Treaties Unequal Treaties Concession Treaties Compromise Treaties 3 Which dynasty ruled china at the time of the Opium Wars? Ming Qing Yuan Song 4 When did the Second Opium War start? 1856 1857 1858 1859 5 What event started the war? Macartney incident Beijing affair Dagu Fort clash Arrow Incident 6 Which country destroyed a Chinese fleet in Fuzhou in 1884? Britain Germany France Spain 7 Which country took Korea from China in 1894? France Japan Britain Russia 8 Which country occupied much of Manchuria? Russia Japan Britain France 9 Which country took the port of Weihaiwei? Russia Japan Britain France 10 When did the Boxer rising start? 1899 1900 1901 1902 11 What provoked the start of the Boxer Rising? Loss of land Increase in the opium trade Western missionaries Development of railways Hodder & Stoughton © 2019 www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview www.hoddereducation.co.uk/historyreview 12 Whose ambassador was shot at the start of the rising? German French British Russian 13 Who wrote 'The Revolutionary Army' in 1903 Sun Yat-sen Zou Rong Li Hongzhang Lu Xun 14 Who organised the Revolutionary -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Hobsbawm 1990, 66. 2. Diamond 1998, 322–33. 3. Fairbank 1992, 44–45. 4. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1–2. 5. Diamond 1998, 323, original emphasis. 6. Crossley 1999; Di Cosmo 1998; Purdue 2005a; Lavely and Wong 1998, 717. 7. Richards 2003, 112–47; Lattimore 1937; Pan Chia-lin and Taeuber 1952. 8. My usage of the term “geo-body” follows Thongchai 1994. 9. B. Anderson 1991, 86. 10. Purdue 2001, 304. 11. Dreyer 2006, 279–80; Fei Xiaotong 1981, 23–25. 12. Jiang Ping 1994, 16. 13. Morris-Suzuki 1998, 4; Duara 2003; Handler 1988, 6–9. 14. Duara 1995; Duara 2003. 15. Turner 1962, 3. 16. Adelman and Aron 1999, 816. 17. M. Anderson 1996, 4, Anderson’s italics. 18. Fitzgerald 1996a: 136. 19. Ibid., 107. 20. Tsu Jing 2005. 21. R. Wong 2006, 95. 22. Chatterjee (1986) was the first to theorize colonial nationalism as a “derivative discourse” of Western Orientalism. 23. Gladney 1994, 92–95; Harrell 1995a; Schein 2000. 24. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1. 25. Cohen 1991, 114–25; Schwarcz 1986; Tu Wei-ming 1994. 26. Harrison 2000, 240–43, 83–85; Harrison 2001. 27. Harrison 2000, 83–85; Cohen 1991, 126. 186 • Notes 28. Duara 2003, 9–40. 29. See, for example, Lattimore 1940 and 1962; Forbes 1986; Goldstein 1989; Benson 1990; Lipman 1998; Millward 1998; Purdue 2005a; Mitter 2000; Atwood 2002; Tighe 2005; Reardon-Anderson 2005; Giersch 2006; Crossley, Siu, and Sutton 2006; Gladney 1991, 1994, and 1996; Harrell 1995a and 2001; Brown 1996 and 2004; Cheung Siu-woo 1995 and 2003; Schein 2000; Kulp 2000; Bulag 2002 and 2006; Rossabi 2004. -

Also by Jung Chang

Also by Jung Chang Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China Mao: The Unknown Story (with Jon Halliday) Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF Copyright © 2019 by Globalflair Ltd. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2019. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019943880 ISBN 9780451493507 (hardcover) ISBN 9780451493514 (ebook) ISBN 9780525657828 (open market) Ebook ISBN 9780451493514 Cover images: (The Soong sisters) Historic Collection / Alamy; (fabric) Chakkrit Wannapong / Alamy Cover design by Chip Kidd v5.4 a To my mother Contents Cover Also by Jung Chang Title Page Copyright Dedication List of Illustrations Map of China Introduction Part I: The Road to the Republic (1866–1911) 1 The Rise of the Father of China 2 Soong Charlie: A Methodist Preacher and a Secret Revolutionary Part II: The Sisters and Sun Yat-sen (1912–1925) 3 Ei-ling: A ‘Mighty Smart’ Young Lady 4 China Embarks on Democracy 5 The Marriages of Ei-ling and Ching-ling 6 To Become Mme Sun 7 ‘I wish to follow the example of my friend Lenin’ Part III: The Sisters and Chiang Kai-shek (1926–1936) 8 Shanghai Ladies 9 May-ling Meets the Generalissimo 10 Married to a Beleaguered -

Chinese Modernisation

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Path of Chinese institutional modernization Sahoo, Ganeswar 15 November 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/24825/ MPRA Paper No. 24825, posted 08 Sep 2010 07:32 UTC PATH OF CHINESE INSTITUTIONAL MODERNIZATION GANESWAR SAHOO Master in Development, Innovation & Change INTRODUCTION: The term ‘Modernization’1 is sort of competition for making modern in appearance or behavior. But in more concisely we can describe ‘Modernization’ is sort of modernity in many ways specially economical, social, scientific, technological, industrial, cultural and even more we can say political progress. As we are discussing the institutional modernization that cover all the above modernity, can be rural development , rationalization and even urbanization to add few. In my opinion, ‘Institutional Modernization’ is a process of development and a progress of various degrees of institutions in a society. If we see the progress today that China has developed a treasure of modernity in terms of its World figure both in economic development and its strong military power with countless path of ups and downs in the past. We are more concerned with the historical study of its institutional modernization than a mere philosophical debate over its development and can discuss its various levels of struggle for ‘Substitute Modernity’2 since mid-19th century(the two opium wars) to till date. FIRST MODERNIZATION: China’s Historical Background After the two opium war from 1840-1860, all high ranking mandarins Zeng Guofan, Zuo Zongtang, Zhang Zhidong and Li Hongzhang during the late Qing Dynasty actively predicated in country’s development what was known as self-strengthening movement. -

A RE-EVALUATION of CHIANG KAISHEK's BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930S

A RE-EVALUATION OF CHIANG KAISHEK’S BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930s A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy DOOEUM CHUNG ProQuest Number: 11015717 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015717 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract Abstract This thesis considers the Chinese Blueshirts organisation from 1932 to 1938 in the context of Chiang Kaishek's attempts to unify and modernise China. It sets out the terms of comparison between the Blueshirts and Fascist organisations in Europe and Japan, indicating where there were similarities and differences of ideology and practice, as well as establishing links between them. It then analyses the reasons for the appeal of Fascist organisations and methods to Chiang Kaishek. Following an examination of global factors, the emergence of the Blueshirts from an internal point of view is considered. As well as assuming many of the characteristics of a Fascist organisation, especially according to the Japanese model and to some extent to the European model, the Blueshirts were in many ways typical of the power-cliques which were already an integral part of Chinese politics. -

Threading on Thin Ice: Resistance and Conciliation in the Jade Marshal’S Nationalism, 1919-1939

THREADING ON THIN ICE: RESISTANCE AND CONCILIATION IN THE JADE MARSHAL’S NATIONALISM, 1919-1939 Mengchuan Lin A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History (Modern China). Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Michael Tsin Miles Fletcher Klaus Larres ©2013 Mengchuan Lin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Mengchuan Lin: Threading On Thin Ice: Resistance and Conciliation in the Jade Marshal’s Nationalism, 1919-1939 (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) The 1920s marked a decade in the history of modern China which is typically referred to as the period of warlords. This period was characterised by political chaos, internal division and internecine warfare between various cliques of military strongmen who controlled China’s numerous provinces. These de facto military dictators of China, known as warlords in historical literature, were customarily construed to be avaricious and self-serving despots who ruled their large territories with little regard for the welfare of their subjects or that of the Chinese nation. My thesis aims to revise these previously held assumptions concerning the historical agency of Chinese warlords by investigating the unusual conduct of a particularly influential warlord: Wu Peifu. Wu’s display of deeply seated nationalistic tendencies throughout his political career, I argue, complicates our understanding of the impact that Chinese warlords exerted on the rise of Chinese national