Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Good and Evil—1

Nietzsche & Asian Philosophy Beyond Good and Evil—1 Beyond good and Evil Preface supposing truth is a woman philosophers like love-sick suitors who don’t understand the woman-truth central problem of philosophy is Plato’s error: denying perspective, the basic condition of all life On the Prejudices of Philosophers 1) questioning the will to truth who is it that really wants truth? What in us wants truth? Why not untruth? 2) origin of the will to truth out of the will to untruth, deception can anything arise out of its opposite? A dangerous questioning? Nietzsche sees new philosophers coming up who have the strength for the dangerous “maybe.” Note in general Nietzsche’s preference for the conditional tense, his penchant for beginning his questioning with “perhaps” or “suppose” or “maybe.” In many of the passages throughout this book Nietzsche takes up a perspective which perhaps none had dared take up before, a perspective to question what had seemed previously to be unquestionable. He seems to constantly be tempting the reader with a dangerous thought experiment. This begins with the questioning of the will to truth and the supposition that, perhaps, the will to truth may have arisen out of its opposite, the will to untruth, ignorance, deception. 3) the supposition that the greater part of conscious thinking must be included among instinctive activities Nietzsche emphasizes that consciousness is a surface phenomenon conscious thinking is directed by what goes on beneath the surface contrary to Plato’s notion of pure reason, the conscious -

Nietzsche's Revaluation of All Values Joseph Anthony Kranak Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Nietzsche's Revaluation of All Values Joseph Anthony Kranak Marquette University Recommended Citation Kranak, Joseph Anthony, "Nietzsche's Revaluation of All Values" (2014). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 415. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/415 NIETZSCHE’S REVALUATION OF ALL VALUES by Joseph Kranak A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2014 ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE’S REVALUTION OF ALL VALUES Joseph Kranak Marquette University, 2014 This dissertation looks at the details of Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the revaluation of all values. The dissertation will look at the idea in several ways to elucidate the depth and complexity of the idea. First, it will be looked at through its evolution, as it began as an idea early in Nietzsche’s career and reached its full complexity at the end of his career with the planned publication of his Revaluation of All Values, just before the onset of his madness. Several questions will be explored: What is the nature of the revaluator who is supposed to be instrumental in the process of revaluation? What will the values after the revaluation be like (a rebirth of ancient values or creation of entirely new values)? What will be the scope of the revaluation? And what is the relation of other major ideas of Nietzsche’s (will to power, eternal return, overman, and amor fati) to the revaluation? Different answers to these questions will be explored. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

REVIEW Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject (New York: Continuum, 2009)

Tomas Marttila 2010 ISSN: 1832-5203 Foucault Studies, No. 10, pp. 173-177, November 2010 REVIEW Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject (New York: Continuum, 2009), ISBN: 978-0826496737 (1) Badiou’s Post-Political Ontology of the Subject Alongside Jacques Ranciere, Jean-Luc Nancy, Gilles Deleuze and Claude Lefort, Alain Badiou is one of the most influential and productive French philosophers of our times. Contemporary French post-foundational philosophy is split into a Lacanian and a Heideggerian stream. The Lacanian stream is more relevant than ever today, as it has been predominant in the works of, amongst others, Ernesto Laclau, Slavoj Žižek and, more recently, Jason Glynos and Yannis Stavrakakis. Marchart has observed the ‘Heideggerian’ influence above all in the works of Alain Badiou, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault.1 Alain Badiou’s Theory of the Subject (French: Théorie du Sujet), published for the first time in 1982, combines both La- canian and Heideggerian philosophy and, in this regard, reflects some of the most central philosophical ideas in recent French post-foundational philosophy. In today’s globalized post-cold-war neo-liberal world, the developments in communist China and the Soviet Union described in Theory of the Subject appear out of time. This anachronism does not, however, account for Badiou’s thought as such. Based on the works of Hegel, Hei- degger and Lacan, Theory of the Subject provides a universal ontology of the political subject. Despite its slightly misleading title, Theory of the Subject is a book about politics as a particular truth event, which makes the political subject appear as the promise of the truth to come. -

Badiou Beyond Formalization? on the Ethics of the Subject

FILOZOFIA ___________________________________________________________________________Roč. 72, 2017, č. 9 BADIOU BEYOND FORMALIZATION? ON THE ETHICS OF THE SUBJECT JAN-JASPER PERSIJN, Centre for the History of Philosophy and Continental Philosophy (HICO), Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Ghent University, Belgium PERSIJN, J.-J.: Badiou beyond Formalization? On the Ethics of the Subject FILOZOFIA 72, 2017, No. 9, pp. 724-735 The paper addresses the tension between Badiou’s claim that his theory of the sub- ject must be considered first of all as a ‘formal’ theory, and a certain genealogical history of his notion of the subject. In the latter case, it seems that a very specific political experience has played a crucial role (at least) for Badiou in his early con- ception of the subject. More particularly, the paper addresses this tension from an ethical perspective. As for the claim repeatedly made in his work (that the subject poses in the first place a formal problem), one can identify an implicitly ethical disposition in the formalization itself. At the same time, there are several formula- tions in his writings that seem to exceed the formal level. The paper examines four concepts or formulations appearing in his three main books (Theory of the Subject, Being and Event, Logics of Worlds) that seem to express a more or less explicit ethical dimension, namely his theory of affects, the principle ‘to decide the unde- cidable’, the contrast between ‘fidelity’ and ‘confidence’ and Badiou’s answer to the question What is it to live? The paper’s aim is to pinpoint the difference be- tween the ethical stance implied in the formal description of Badiou’s theory of the subject and an explicit ‘ethics of the subject’. -

Extrait Ma Junwu

Avertissement : Ce texte n’est pas définitivement achevé. Il s’agit d’un fragment de ma thèse en cours de rédaction sur le darwinisme en Chine. Néanmoins, il m’a paru utile pour la poursuite de mon travail de le publier en l’état pour permettre à un lectorat intéressé par le sujet et/ou aux universitaires d’en prendre connaissance, devant la difficulté d’avoir un retour sur mon travail, notamment chez les sinologues. Ma Junwu, premier traducteur de Darwin Ingénieur, éducateur, poète et homme politique, Ma Junwu (son vrai prénom est Daoning) est le premier et le plus influent traducteur de Darwin en chinois de la première moitié du XXe siècle. Par l’impact incontestable et durable de ses traductions d’œuvres occidentales (à part Darwin, il faut citer notamment Rousseau, J. S. Mill, Spencer et Haeckel), c’est certainement la personnalité la plus typique de la philosophie évolutionniste chinoise, bien que son rôle soit encore sous-estimé par les commentateurs contemporains dans ce domaine1. Il est né le 17 juillet 1881 à Gongcheng, aujourd’hui un district de la région de Guilin (province de Guangxi), d’un parent fonctionnaire2. Durant son enfance, Ma suit une éducation classique privée mais dès l’âge de 16 ans (en 1897), il s’intéresse au programme de réformes constitutionnelles de Kang Youwei. Il suit de près les événements des 100 jours de réformes, l’année suivante. En 1899, il entre à l’école Tiyong (Tiyong daxue) à Guilin, l’une des nouvelles écoles qui s’ouvrent au « savoir occidental ». Dans le cadre de ses études secondaires, Ma y étudie notamment les mathématiques (sa spécialité de l’époque), l’anglais et l’histoire3. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 159 2nd International Conference on Judicial, Administrative and Humanitarian Problems of State Structures and Economical Subjects (JAHP 2017) Modern Chinese Students Studying in Japan and Xiangshan Society Peng Jiao College of Humanities Jinan University Zhuhai, China Abstract—The defeat of the Sino-Japanese war in 1894 country. China signed Treaty of Shimonoseki. We ceded greatly changed the Chinese people's ideas and thoughts. territory and paid indemnities to Japan. It greatly shocked Chinese people realize that Japan has developed because of Chinese and aroused our reflection. This kind of reflection is sending students abroad. Domestic media called on the based on the re-examination of Japan, which greatly changed government to send students abroad. In 1902, the Qing our people's ideas and thoughts. Chinese have come to realize government implemented a new policy requiring all localities to that the development of Japan in just a few decades was due send students to Japan. The number of students going to Japan to sending students to study abroad. Therefore, domestic had soared. In this trend, a large number of Xiangshan media called on the government to send students to study in students followed it and also went to Japan. After the students Japan. Governors including Zhang Zhidong advocated returned to their hometown, they ran a newspaper and sending students to study abroad. He vigorously advocated organized societies for revolutionary propaganda, and also managed education business in hometown to expand Esperanto; sending students to study abroad in his Encourage to Study these activities have affected the changes of modern Xiangshan Abroad published in April 1898. -

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution Was Also a Radical Educational Institution Modeled After Socialist 1991 36 for This Information, See Ibid., 58

only by rephrasing earlier problems in a new discourse that is unmistakably modern in its premises and sensibilities; even where the answers are old, the questions that produced them have been phrased in the problematic of a new historical situation. The problem was especially acute for the first generation of intellec- Anarchism in the Chinese tuals to become conscious of this new historical situation, who, Revolution as products of a received ethos, had to remake themselves in the very process of reconstituting the problematic of Chinese thought. Anarchism, as we shall see, was a product of this situation. The answers it offered to this new problematic were not just social Arif Dirlik and political but sought to confront in novel ways its demands in their existential totality. At the same time, especially in the case of the first generation of anarchists, these answers were couched in a moral language that rephrased received ethical concepts in a new discourse of modernity. Although this new intellectual problematique is not to be reduced to the problem of national consciousness, that problem was important in its formulation, in two ways. First, essential to the new problematic is the question of China’s place in the world and its relationship to the past, which found expression most concretely in problems created by the new national consciousness. Second, national consciousness raised questions about social relationships, ultimately at the level of the relationship between the individual and society, which were to provide the framework for, and in some ways also contained, the redefinition of even existential questions. -

The Towers of Yue Olivia Rovsing Milburn Abstract This Paper

Acta Orientalia 2010: 71, 159–186. Copyright © 2010 Printed in Norway – all rights reserved ACTA ORIENTALIA ISSN 0001-6438 The Towers of Yue Olivia Rovsing Milburn Seoul National University Abstract This paper concerns the architectural history of eastern and southern China, in particular the towers constructed within the borders of the ancient non-Chinese Bai Yue kingdoms found in present-day southern Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong provinces. The skills required to build such structures were first developed by Huaxia people, and hence the presence of these imposing buildings might be seen as a sign of assimilation. In fact however these towers seem to have acquired distinct meanings for the ancient Bai Yue peoples, particularly in marking a strong division between those groups whose ruling houses claimed descent from King Goujian of Yue and those that did not. These towers thus formed an important marker of identity in many ancient independent southern kingdoms. Keywords: Bai Yue, towers, architectural history, identity, King Goujian of Yue Introduction This paper concerns the architectural history of eastern and southern China, in particular the relics of the ancient non-Chinese kingdoms found in present-day southern Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian and 160 OLIVIA ROVSING MILBURN Guangdong provinces. In the late Spring and Autumn period, Warring States era, and early Han dynasty these lands formed the kingdoms of Wu 吳, Yue 越, Minyue 閩越, Donghai 東海 and Nanyue 南越, in addition to the much less well recorded Ximin 西閩, Xiyue 西越 and Ouluo 甌駱.1 The peoples of these different kingdoms were all non- Chinese, though in the case of Nanyue (and possibly also Wu) the royal house was of Chinese origin.2 This paper focuses on one single aspect of the architecture of these kingdoms: the construction of towers. -

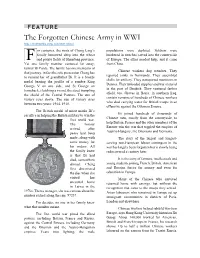

FEATURE the Forgotten Chinese Army in WWI Or Centuries, the Roots of Cheng Ling’S Populations Were Depleted

FEATURE The Forgotten Chinese Army in WWI http://multimedia.scmp.com/ww1-china/ or centuries, the roots of Cheng Ling’s populations were depleted. Soldiers were family burrowed deep into the wheat hunkered in trenches carved into the countryside F and potato fields of Shandong province. of Europe. The allies needed help, and it came Yet one family member ventured far away, from China. farmer Bi Cuide. The family has one memento of Chinese workers dug trenches. They that journey, in fact the sole possession Cheng has repaired tanks in Normandy. They assembled to remind her of grandfather Bi. It is a bronze shells for artillery. They transported munitions in medal bearing the profile of a sombre King Dannes. They unloaded supplies and war material George V on one side, and St George on in the port of Dunkirk. They ventured farther horseback, clutching a sword, the steed trampling afield, too. Graves in Basra, in southern Iraq, the shield of the Central Powers. The sun of contain remains of hundreds of Chinese workers victory rises above. The sun of victory rises who died carrying water for British troops in an between two years: 1914, 1918. offensive against the Ottoman Empire. The British medal of merit marks Bi’s Bi joined hundreds of thousands of sacrifice in helping the British military to win the Chinese men, mostly from the countryside, to first world war. help Britain, France and the other members of the The honour Entente win the war that toppled the empires of arrived after Austria-Hungary, the Ottomans and Germany. -

Science and Technology in Modern China, 1880S-1940S

Science and Technology in Modern China, 1880s-1940s Edited by Jing Tsu and Benjamin A. Elman LEIDEN | BOSTON This is a digital offprint for restricted use only | © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents List of Figures vii Notes on Contributors ix Introduction 1 Jing Tsu and Benjamin A. Elman Toward a History of Modern Science in Republican China 15 Benjamin A. Elman Historiography of Science and Technology in China The First Phase 39 Iwo Amelung Disciplining the National Essence Liu Shipei and the Reinvention of Ancient China’s Intellectual History 67 Joachim Kurtz Science in Translation Yan Fu’s Role 93 Shen Guowei Chinese Scripts, Codes, and Typewriting Machines 115 Jing Tsu Semiotic Sovereignty The 1871 Chinese Telegraph Code in Historical Perspective 153 Thomas S. Mullaney Proofreading Science Editing and Experimentation in Manuals by a 1930s Industrialist 185 Eugenia Lean The Controversy over Spontaneous Generation in Republican China Science, Authority, and the Public 209 Fa-ti Fan Bridging East and West through Physics William Band at Yenching University 245 Danian Hu Periodical Space Language and the Creation of Scientific Community in Republican China 269 Grace Shen This is a digital offprint for restricted use only | © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents Operatic Escapes Performing Madness in Neuropsychiatric Beijing 297 Hugh Shapiro Index 327 Contents Notes on Contributors ix Introduction 1 Jing Tsu and Benjamin A. Elman Introduction 1 Toward a History of Modern Science in Republican China 15 Benjamin A. Elman 15 Historiography of Science and Technology in China 39 The First Phase 39 Iwo Amelung 39 Disciplining the National Essence 67 Liu Shipei and the Reinvention of Ancient China’s Intellectual History 67 Joachim Kurtz 67 Science in Translation 93 Yan Fu’s Role 93 Shen Guowei 93 Chinese Scripts, Codes, and Typewriting Machines 115 Jing Tsu 115 Semiotic Sovereignty 153 The 1871 Chinese Telegraph Code in Historical Perspective 153 Thomas S. -

Black Flag White Masks: Anti-Racism and Anarchist Historiography

Black Flag White Masks: Anti-Racism and Anarchist Historiography Süreyyya Evren1 Abstract Dominant histories of anarchism rely on a historical framework that ill fits anarchism. Mainstream anarchist historiography is not only blind to non-Western elements of historical anarchism, it also misses the very nature of fin de siècle world radicalism and the contexts in which activists and movements flourished. Instead of being interested in the network of (anarchist) radicalism (worldwide), political historiography has built a linear narrative which begins from a particular geographical and cultural framework, driven by the great ideas of a few father figures and marked by decisive moments that subsequently frame the historical compart- mentalization of the past. Today, colonialism/anti-colonialism and imperialism/anti-imperialism both hold a secondary place in contemporary anarchist studies. This is strange considering the importance of these issues in world political history. And the neglect allows us to speculate on the ways in which the priorities might change if Eurocentric anarchist histories were challenged. This piece aims to discuss Eurocentrism imposed upon the anarchist past in the form of histories of anarchism. What would be the consequences of one such attempt, and how can we reimagine the anarchist past after such a critique? Introduction Black Flag White Masks refers to the famous Frantz Fanon book, Black Skin White Masks, a classic in anti-colonial studies, and it also refers to hidden racial issues in the history of the black flag (i.e., anarchism). Could there be hidden ethnic hierarchies in the main logic of anarchism's histories? The huge difference between the anarchist past and the histories of anarchism creates the gap here.