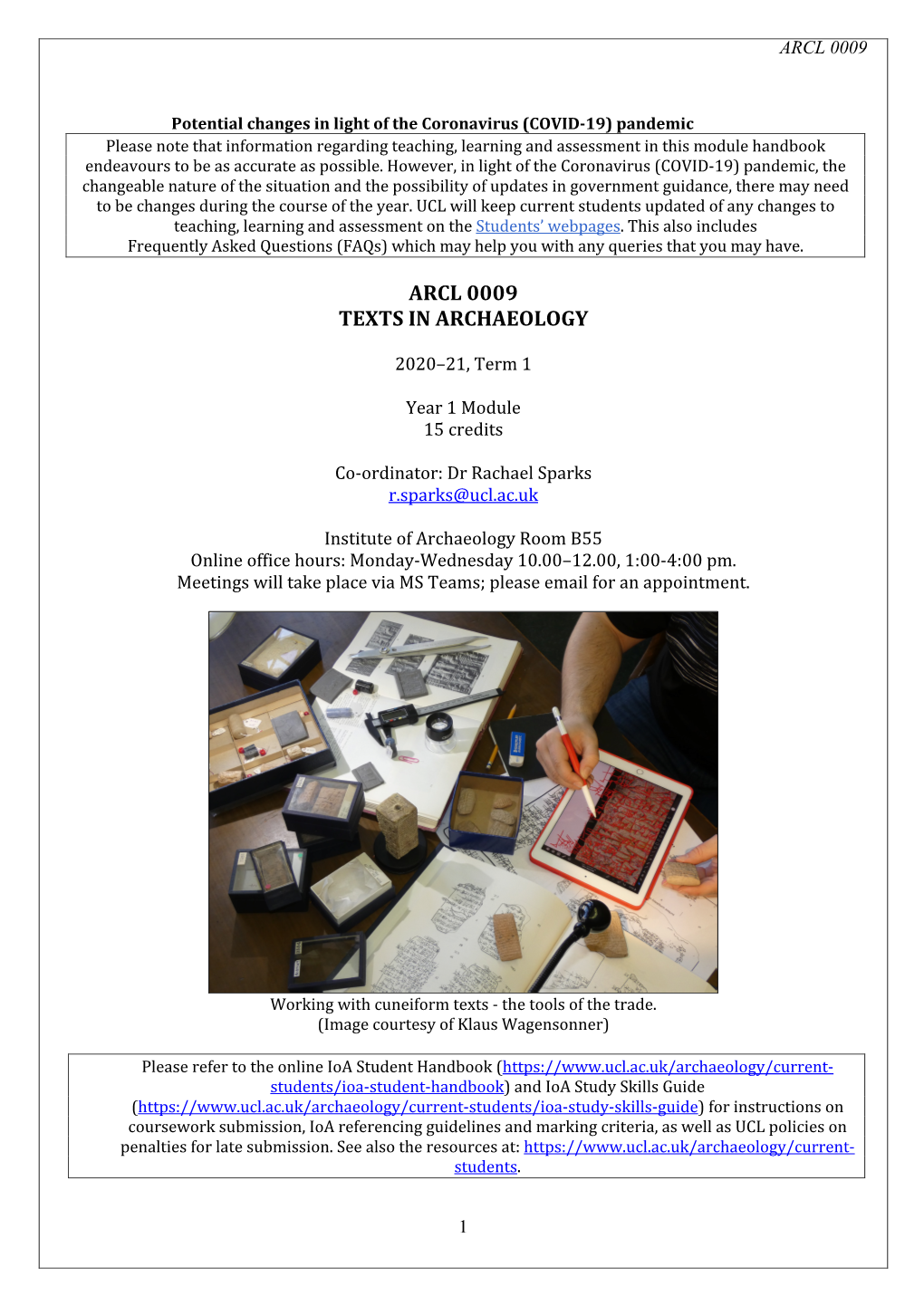

Arcl 0009 Texts in Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tayinat's Building XVI: the Religious Dimensions and Significance of A

Tayinat’s Building XVI: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua by Douglas Neal Petrovich A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Douglas Neal Petrovich, 2016 Building XVI at Tell Tayinat: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua Douglas N. Petrovich Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2016 Abstract After the collapse of the Hittite Empire and most of the power structures in the Levant at the end of the Late Bronze Age, new kingdoms and powerful city-states arose to fill the vacuum over the course of the Iron Age. One new player that surfaced on the regional scene was the Kingdom of Palistin, which was centered at Kunulua, the ancient capital that has been identified positively with the site of Tell Tayinat in the Amuq Valley. The archaeological and epigraphical evidence that has surfaced in recent years has revealed that Palistin was a formidable kingdom, with numerous cities and territories having been enveloped within its orb. Kunulua and its kingdom eventually fell prey to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which decimated the capital in 738 BC under Tiglath-pileser III. After Kunulua was rebuilt under Neo- Assyrian control, the city served as a provincial capital under Neo-Assyrian administration. Excavations of the 1930s uncovered a palatial district atop the tell, including a temple (Building II) that was adjacent to the main bit hilani palace of the king (Building I). -

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

January-February 2020

january-february 2020 Burying the Truth Could Egypt Fall to Iran? JERUSALEM’S ORIGINS JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2020 | VOL. 2, NO. 1 | circulation: 1,193 FROM THE EDITOR The Incredible Origins of Ancient Jerusalem 1 Burying the Truth 6 Iran to Shift Focus to Africa? 11 Could Egypt Fall to Iran? 12 INFOGRAPHIC Top 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2019 16 Archaeology Reveals Jerusalem’s Origins 22 julia goddard (cover) gary dorning (inside spread)/Watch Jerusalem Artist'sii watch rendition jerusalem of the Garden of Eden from the editor | By Gerald Flurry The Incredible Origins of Ancient Jerusalem An inspiring overview of the world’s most important and famous city he history of Jerusalem is the history of the world.” That is the opening line of “TJerusalem, an illuminating book chronicling the history of this city, written by British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore. In the introduction, Montefiore describes how absolutely central Jerusalem is in the history of human civilization, especially in the history and theology of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Using examples and anecdotes, he shows that Jerusalem has been a focal point for humanity from the beginning. He then asks this crucial question: “Of all the places in the world, why Jerusalem?” This question gets to the essence of understanding Jerusalem. Montefiore writes, “The site was remote from the trade routes of the Mediterranean coast; it was short of water, baked in the summer sun, chilled by winter winds, its jagged rocks blistered and inhospitable.” Despite these disadvantages, Jerusalem became the “center of the Earth.” Why? Anyone who is even the slightest bit familiar with the Bible knows that Jerusalem is at the heart of the biblical narrative. -

A Time to Gather Stones

A Time to Gather Stones A look at the archaeological evidences of peoples and places in the scriptures This book was put together using a number of sources, none of which I own or lay claim to. All references are available as a bibliography in the back of the book. Anything written by the author will be in Italics and used mainly to provide information not stated in the sources used. This book is not to be sold Introduction Eccl 3:1-5 ; To all there is an appointed time, even time for every purpose under the heavens, a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pull up what is planted; a time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to tear down, and a time to build up; a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to throw away stones, and a time to gather stones… Throughout the centuries since the final pages of the bible were written, civilizations have gone to ruin, libraries have been buried by sand and the foot- steps of the greatest figures of the bible seem to have been erased. Although there has always been a historical trace of biblical events left to us from early historians, it’s only been in the past 150 years with the modern science of archaeology, where a renewed interest has fueled a search and cata- log of biblical remains. Because of this, hundreds of archaeological sites and artifacts have been uncovered and although the science is new, many finds have already faded into obscurity, not known to be still existent even to the average believer. -

The Bible in Its World: the Bible & Archaeology Today

Kenneth A. Kitchen, The Bible in its World: The Bible and Archaeology Today. Exeter: The Paternoster Press, 1977. Pbk. pp.168. The Bible in its World: The Bible & Archaeology Today Kenneth A. Kitchen Contents Preface 7 Chapter 1 Archaeology―a Key to the Past 9 2 The Most Ancient World 19 3 Ebla―Queen of Ancient Syria 37 4 Founding Fathers in Canaan and Egypt 56 5 Birth of a Nation 75 6 Kings and Poets 92 7 Wars and Rumours of Wars 108 8 Exile and Return 120 9 In the Fullness of Time 127 Outline Table of Dates 135 Notes [now moved to chapter footnotes] 138 Select Bibliography 154 Maps: Ancient Near East; Ebla; Palestine 159-161 Index 162 [p.7] Preface Archaeology and the Bible remains a theme of unending fascination. The ancient Near East teemed with the life of rich and complex civilizations that show both change and continuity in how people lived in that part of our planet across a span of several thousand years. The study of the physical remains and of the innumerable inscriptions from the ancient Near-Eastern world is itself a complex and many-sided task. Yet, as that world is the Bible’s world, the attempt is a necessary venture in order to see the books of the Bible in their ancient context. The enduring central themes of the Bible stand out clearly enough of themselves; but a more detailed understanding of the biblical writings can be gained by viewing them in relation to their ancient context. Biblical studies have long been hindered by the persistence of long-outdated philosophical and literary theories (especially of 19th-century stamp), and by wholly inadequate use of first-hand sources in appreciating the earlier periods of the Old Testament story in particular. -

357773-Sample.Pdf

Sample file THE BOOK OF RANDOM TABLES STEAMPUNKSample file CREDITS Written by Matt Davids Layout & Design by Matt Davids Cover & Interior Art by Albert Robida WWW.DICEGEEKS.COMSample file Contents copyright © 2021 dicegeeks. All rights reserved. All images in the public domain. GET MORE FREE RANDOM TABLES AT WWW.DICEGEEKS.COM/FREE Sample file TABLE OF CONTENTS How to Use this Book...................................................................................5 ITEMS & THINGS Airship Cargo................................................................................................7 Artifacts #1..............................................................................................8-9 Artifacts #2...........................................................................................10-11 Drugs and Medicines..................................................................................12 Items in a Desk...........................................................................................13 Items in a Scientist’s Lab.............................................................................14 Items in a Study..........................................................................................15 Steam Engine and Boiler Parts...................................................................16 Victorian Era Books #1...............................................................................18 Victorian Era Books #2..............................................................................19 FAMOUS VICTORIANS -

CUP Liverani P1-3

Studies in Egyptology and the Ancient Near East This interdisciplinary series publishes works on the ancient Near East in antiquity, including the Graeco-Roman period, and is open to specialized studies as well as to works of synthesis or comparison. Series Editor John Baines, Oriental Institute, University of Oxford Editorial Board Jeremy Black (University of Oxford) Alan Bowman (University of Oxford) Erik Hornung (University of Basel) Anthony Leahy (University of Birmingham) Peter Machinist (Harvard University) Piotr Michalowski (University of Michigan) David O'Connor (Institute of Fine Arts, New York University) D.T. Potts (University of Sydney) Dorothy Thompson (University of Cambridge) Pascal Vernus (Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris) Norman Yoffee (University of Michigan) Also Forthcoming in this Series Local Power in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia Andrea Seri Statue of Idri-Mi Courtesy of the British Museum Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography MARIO LIVERANI Edited and Introduced by Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop LONDON Published by Equinox Publishing Ltd Unit 6 The Village 101 Amies St. London SW11 2JW www.equinoxpub.com First published in the UK 2004 © Mario Liverani 2004 Introduction and editorial apparatus © Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in -

Umma4n-Manda and Its Significance in the First Millennium B.C

Umma 4n-manda and its Significance in the First Millennium B.C. Selim F. Adalı Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts Department of Classics and Ancient History University of Sydney 2009 Dedicated to the memory of my grandparents Ferruh Adalı, Melek Adalı, Handan Özker CONTENTS TABLES………………………………………………………………………………………vi ABBREVIATIONS…………………………………………………………………………..vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………………...xiv ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………..xv INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………...xvi 1 SOURCES AND WRITTEN FORM………………………………………………………...1 1.1 An Overview 1.2 The Written Forms in the Old Babylonian Omens 1.3 The Written Form in the Statue of Idrimi 2 ETYMOLOGY: PREVIOUS STUDIES…………………………………………………...20 2.1 The Proposed ma du4 Etymology 2.1.1 The Interchange of ma du4 and manda /mandu (m) 2.2 The Proposed Hurrian Origin 2.3 The Proposed Indo-European Etymologies 2.3.1 Arah ab} the ‘Man of the Land’ 2.3.2 The Semitic Names from Mari and Choga Gavaneh 2.4 The Proposed man ıde4 Etymology 2.5 The Proposed mada Etymology 3 ETYMOLOGY: MANDUM IN ‘LUGALBANDA – ENMERKAR’……………………44 3.1 Orthography and Semantics of mandum 3.1.1 Sumerian or Akkadian? 3.1.2 The Relationship between mandum, ma tum4 and mada 3.1.3 Lexical Lists 3.1.3.1 The Relationship between mandum and ki 3.1.4 An inscription of Warad-Sın= of Larsa 3.2 Lugalbanda II 342-344: Previous Interpretations and mandum 3.3 Lugalbanda II 342-344: mandum and its Locative/Terminative Suffix 4 ETYMOLOGY: PROPOSING MANDUM………………………………………………68 4.1 The Inhabited World and mandum 4.1.1 Umma -

The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality

THE AURA IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL MATERIALITY RETHINKING PRESERVATION IN THE SHADOW OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE The project is part of the exhibition LA RISCOPERTA DI UN CAPOLAVORO 12 March – 28 June 2020 Palazzo Fava, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Bologna A project of: Under the patronage of: A collection of essays assembled by Factum Foundation All projects carried out by the Factum Foundation are collaborative to accompany the exhibition and there are many people to thank. This is not the place to name everyone but some people have done a great deal to make all this The Materiality of the Aura: work possible including: Charlotte Skene Catling, Otto Lowe, New Technologies for Preservation Tarek Waly, Simon Schaffer, Pasquale Gagliardi, Fondazione Giorgio Cini and everyone in ARCHiVe, Bruno Latour, Hartwig Fischer, Palazzo Fava, Bologna Jerry Brotton, Roberto Terra, Cat Warsi, John Tchalenko, Manuela 12 March – 28 June 2020 Mena, Peter Glidewell, The Griffi th Institute, Emma Duncan, Lord Pontificio Consiglio della Cultura Rothschild, Fabia Bromofsky, Ana Botín, Paloma Botín, Lady Helen Hamlyn, Ziyavudin and Olga Magomedov, Rachid Koraïchi, Andrew ‘Factum Arte’ can be translated from the Latin as ‘made with Edmunds, Colin Franklin, Ed Maggs, the Hereford Mappa Mundi skill’. Factum’s practice lies in mediating and transforming material. Trust, Rosemary Firman, Philip Hewat-Jaboor, Helen Dorey, Peter In collaboration with: Its approach has emerged from an ability to record and respond to Glidewell, Purdy Rubin, Fernando Caruncho, Susanne Bickel, the subtle visual information manifest in the physical world around Markus Leitner and everyone at the Swiss Embassy in Cairo, Jim us. -

In Remembrance of Me

oi.uchicago.edu IN REMEMBRANCE OF ME 1 oi.uchicago.edu Digital reconstruction of the Katumuwa Stele chamber (Travis Saul) oi.uchicago.edu IN REMEMBRANCE OF ME FEASTING WITH THE DEAD IN THE ANCIENT MIDDLE EAST edited by Virginia Rimmer Herrmann and J. David Schloen with new photography by Anna R. Ressman oRiental instiTuTe muSeum publicATionS 37 THe oRiental instiTuTe of THe uniVeRSiTy of cHicAgo oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2014932919 ISBN-10:1614910170 ISBN-13: 978-1-61491-017-6 © 2014 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition In Remembrance of Me: Feasting with the Dead in the Ancient Middle East April 8, 2014–January 4, 2015 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 37 Series Editors: Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois, 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu Illustration Credits Front cover: Katumuwa Stele Cast (OIM C5677). Cat. Nos. 1–2. Digitally rendered by Travis Saul. Cover designed by Keeley Marie Stitt Photography by Anna R. Ressman: Catalog Nos. 1, 3, 5, 7–12, 14–15, 18–25, 27–52; Figures 11.1 and C7 Photography by K. Bryce Lowry: Catalog Nos. 53–54, 56–57 Printed by Corporate Graphics, North Mankato, Minnesota, through Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky, USA The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Late Bronze Age Tell Atchana (Alalakh): Stratigraphy, Chronology, History

Late Bronze Age Tell Atchana (Alalakh): Stratigraphy, Chronology, History AMIR SUMAKAI FINK To Joe and Jeanette Neubauer Synopsis The following work is a re-structuring of my doctoral thesis, which re-visits the Late Bronze Age stratigraphy, chronology and history of Tell Atchana as recorded by Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1930s and 1940s. I offer both a detailed analysis of the material culture of Late Bronze Age Alalakh and a political history of the region following the destruction of the Level IVW palace. My first step in this study was to understand the way in which the plans of Tell Atchana that Woolley published should be interpreted, and the implications thereof. The next was to establish the correct location, absolute and relative, of the Level IW temples. Then followed an analysis of the stratigraphy of the Levels IV–0W temples, which brought me to advance two major proposals: 1) that the Level IVAF temple had an annexe and 2) that the walls and finds attributed to the annexe to the Level IBW temple should be associated with the Paluwa Shrine, which postdates the Level IW temples. Based on the finds in each of the later temples, I corrected their dates and reassigned them to Tell Atchana levels, different from those to which they were originally assigned. This resulted, among other things, in a detailed study of the find-spot of the statue of Idrimi, now newly attributed to Level IVBF, the first half of the fourteenth century B.C.E., probably not more than a few decades after the death of Idrimi, king of Alalakh. -

Ancient Israelite and Early Jewish Literature

Ancient Israelite and Early Jewish Literature Ancient Israelite and Early Jewish Literature Translated by Brian Doyle by T.C. Vriezen A.S. van der Woude BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 Translated with financial support from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Vriezen, T.C. (Theodoor Christiaan), 1899–1981. [Oudisraëlitische en vroegjoodse literatuur. English] Ancient Israelite and early Jewish literature / translated by Brian Doyle ; by T.C. Vriezen, A.S. van der Woude. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-14181-2 (alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T.—Introductions. 2. Bible. O.T. Apocrypha—Introductions. 3. Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Introductions. 4. Dead Sea scrolls. I. Woude, A.S. van der. II. Title. BS1140.3.V7513 2004 296.1—dc22 2004057552 ISBN 90 04 14181 2 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright ©1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used with permission. All rights reserved. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 09123, USA.