In Remembrance of Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Innovative Model to Predict Earthquakes in Indian Peninsula Y

British Journal of Earth Sciences Research Vol.3, No.1, pp.42-62, September 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) AN INNOVATIVE MODEL TO PREDICT EARTHQUAKES IN INDIAN PENINSULA Y. V. Subba Rao Visiting Professor, Department of Jyotish Rashtriya Sanskrit University, Tirupati, A.P., India ABSTRACT: Can earthquakes be predicted? So far, the answer is no. Scientists are unlikely to be ever able to predict earthquakes with any amount of certainty, according to the United States Geological Survey Apr 25, 2013. An Innovative Model for Earthquake Prediction (IMEP) proposed in this paper is a combination of Vedic Astrology (Vedānga), Varāha Mihira’s Brihat Samhita and scientific data of magnetic variations, structural geology such as fault zones, tectonic plates’ directions, loose soil areas of all the earthquakes occurred in Indian Peninsula shield over a period of 200 years. In the course of preparation of this paper, it is observed that the earthquakes occured at regular intervals of about 11 years and mostly during bright fortnight due to extraordinary astronomical phenomena occurring in the planets and special movements of the heavenly bodies. Vedānga and Brihat Samhita state that earthquakes are caused by eclipses of the luminaries. It is, therefore, plausible to predict earthquakes in a specific locality within a specific time limit utilising this model. However, as an initial step, the present model has been designed for application for India. The next earthquake in Indian peninsula is predicted to occur on Wednesday, the 16th March, 2016 on the basis of the proposed hypothesis model. -

R262a4 1922.Pdf

-AMERICAN ROAD MAP SUCTCESS First Steps in Psychology . BY FRED S. RAWSON SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Nineteen-Twenty-Two CITY PRINTING CO, 722 Market street, San Diego, California 1 ‘i,, - -t, J , . , SPECIAL NOTICE. For psychological reasons, never loan this book. Keep it for a ready reference for yourself or members of your family. Tell your friends where to get one. But, hold on to your own copy. It is your own private Key to the Temple of Success. Use it daily. It will grow brighter with use. Become familiar with every one of the Thirty-three Elements of Success. Mail orders filled the same day they are received. $1.00, Cloth Bound. THE FREDERICK S. RAWSON PUBLISHING CO. 724 BROADWAY, SAN DIEGO. CALIF. A. K. Aberg, Manager Mail Order Dept. PREFACE. THE ROAD MAP TO SUCCESS, THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CHAIN OF LIFE. All nature grows in silence. All growth is in silence. When you want any new ideas, go where it is quiet; get into the silence, absolute silence. Listen into your own head. When you have adopted this method as a means of getting inspiration, you will never have any trouble getting new ideas. They will come faster than you can write them. I am as positive as I can be, that no person can create anything of any consequence, under fear, excitement, or noise, where constructive thought is required. Have you not heard it said, “For God’s sake, keep still and let me think !“? The idea of the Psychological Chain of Life was received early one morning while lying in bed. -

Dr Matthew Rimmer Professor of Intellectual Property and Innovation Law Faculty of Law Queensland University of Technology

MARCH 2016 THE TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, PUBLIC HEALTH, AND ACCESS TO ESSENTIAL MEDICINES Zahara Heckscher Protests against the TPP DR MATTHEW RIMMER PROFESSOR OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND INNOVATION LAW FACULTY OF LAW QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Queensland University of Technology 2 George Street GPO Box 2434 Brisbane Queensland 4001 Australia Work Telephone Number: (07) 31381599 1 Executive Summary This submission provides a critical analysis of a number of Chapters in the Trans-Pacific Partnership addressing intellectual property, public health, and access to essential medicines – including Chapter 18 on Intellectual Property, Chapter 9 on Investment, and Annex 26 on ‘Healthcare Transparency.’ The United States Trade Representative has argued: ‘The Intellectual Property chapter also includes commitments to promote not only the development of innovative, life-saving drugs and treatments, but also robust generic medicine markets.’ The United States maintained: ‘Drawing on the principles underlying the “May 10, 2007” Congressional-Executive Agreement, included in agreements with Peru, Colombia, Panama, and Korea, the chapter includes transitions for certain pharmaceutical IP provisions, taking into account a Party’s level of development and capacity as well as its existing laws and international obligations.’ The United States Trade Representative also argued that the agreement protected public health: ‘The chapter incorporates the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, and confirms -

HPSC0011 STS Perspectives on Big Problems Course Syllabus

HPSC0011 STS Perspectives on Big Problems Course Syllabus 2020-21 session | STS Staff, course coordinator Dr Cristiano Turbil | [email protected] Course Information This module introduces students to the uses of STS in solving big problems in the contemporary world. Each year staff from across the spectrum of STS disciplines – History, Philosophy, Sociology and Politics of Science – will come together to teach students how different perspectives can shed light on issues ranging from climate change to nuclear war, private healthcare to plastic pollution. Students have the opportunity to develop research and writing skills, and assessment will consist of a formative and a final essay. Students also keep a research notebook across the course of the module This year’s topic is Artificial Intelligence. Basic course information Moodle Web https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=7420 site: Assessment: Formative assessment and essay Timetable: See online timetable Prerequisites: None Required texts: Readings listed below Course tutor(s): STS Staff, course coordinator Dr Cristiano Turbil Contact: [email protected] | Web: https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=7420 Office location: Online for TERM 1 Schedule UCL Date Topic Activity Wk 1 & 2 20 7 Oct Introduction and discussion of AI See Moodle for details as ‘Big Problem’ (Turbil) 3 21 14 Oct Mindful Hands (Werret) See Moodle for details 4 21 14 Oct Engineering Difference: the Birth See Moodle for details of A.I. and the Abolition Lie (Bulstrode) 5 22 21 Oct Measuring ‘Intelligence’ (Cain & See Moodle for details Turbil) 6 22 21 Oct Artificial consciousness and the See Moodle for details ‘race for supremacy’ in Erewhon’s ‘The Book of the Machines’ (1872) (Cain & Turbil) 7 & 8 23 28 Oct History of machine intelligence in See Moodle for details the twentieth century. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

The British Museum Report and Accounts for the Year

The British Museum REPOrt AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 HC 400 £14.75 The British Museum REPOrt AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Museums and Galleries Act 1992 (c.44) S.9(8) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 12 July 2012 HC 400 London: The Stationery Office £14.75 The British Museum Account 2011-2012 © The British Museum (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as The British Museum copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk ISBN: 9780102976199 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2481871 07/12 21557 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum The British Museum Account 2011-2012 Contents Page Trustees’ and Accounting Officer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 5 Constitution and operating environment 5 Governance statement 5 Subsidiaries 10 Friends’ organisations 10 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 10 To manage and research the collection more effectively 10 Collection 10 Conservation -

Tayinat's Building XVI: the Religious Dimensions and Significance of A

Tayinat’s Building XVI: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua by Douglas Neal Petrovich A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Douglas Neal Petrovich, 2016 Building XVI at Tell Tayinat: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua Douglas N. Petrovich Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2016 Abstract After the collapse of the Hittite Empire and most of the power structures in the Levant at the end of the Late Bronze Age, new kingdoms and powerful city-states arose to fill the vacuum over the course of the Iron Age. One new player that surfaced on the regional scene was the Kingdom of Palistin, which was centered at Kunulua, the ancient capital that has been identified positively with the site of Tell Tayinat in the Amuq Valley. The archaeological and epigraphical evidence that has surfaced in recent years has revealed that Palistin was a formidable kingdom, with numerous cities and territories having been enveloped within its orb. Kunulua and its kingdom eventually fell prey to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which decimated the capital in 738 BC under Tiglath-pileser III. After Kunulua was rebuilt under Neo- Assyrian control, the city served as a provincial capital under Neo-Assyrian administration. Excavations of the 1930s uncovered a palatial district atop the tell, including a temple (Building II) that was adjacent to the main bit hilani palace of the king (Building I). -

The Christian Remains of the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse

1974, 3) THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST 69 The Christian Remains of the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse OTTO F. A. MEINARDU S Athens, Greece Some months ago, I revisited the island of Patmos and the sites of the seven churches to which letters are addressed in the second and third chap- ters of the book of Revelation. What follows is a report on such Christian remains as have survived and an indication of the various traditions which have grown up at the eight locations, where, as at so many other places in the Orthodox and Latin world, piety has sought tangible localization. I set out from Piraeus and sailed to the island of Patmos, off the Turkish coast, which had gained its significance because of the enforced exile of God's servant John (Rev. 1:1, 9) and from the acceptance of the Revelation in the NT canon. From the tiny port of Skala, financial and tourist center of Patmos, the road ascends to the 11th century Greek Orthodox monastery of St. John the Theologian. Half way to this mighty fortress monastery, I stopped at the Monastery of the Apocalypse, which enshrines the "Grotto of the Revelation." Throughout the centuries pilgrims have come to this site to receive blessings. When Pitton de Tournefort visited Patmos in 1702, the grotto was a poor hermitage administered by the bishop of Samos. The abbot presented de Tournefort with pieces of rock from the grotto, assuring him that they could expel evil spirits and cure diseases. Nowadays, hundreds of western tourists visit the grotto daily, especially during the summer, and are shown those traditional features which are related in one way or another with the vision of John. -

Calendar 2020

AUGUST 2020 Sravana - Bhadrapada 2077 Shukla Paksha Dwadashi Friendship Day Krishna Paksha Sashthi Krishna Paksha Dwadashi Rishi Panchami Festivals, Vrats & Holidays Shravana Bhadra Bhadra 1 Pradosh Vrat, Shani Trayodashi ३० २ ९ १६ २३ Sun 30 27 2 29 9 6 16 12 23 20 2 Friendship Day Uttara Ashadha Purva Ashadha Revati Ardra Chitra 3 Shravana Purnima रव. Makara Simha Dhanu Karka Meena Karka Mithuna Karka Kanya Simha Raksha Bandhan Trayodashi Onam Raksha Bandhan Krishna Paksha Sashthi Krishna Paksha Trayodashi Shukla Paksha Sashthi Narali Purnima,Sanskrit Diwas Bhadra Bhadra Bhadra Bhadra Gayatri Jayanti ३१ ३ १० १७ २४ MON 31 28 3 10 6 17 13 24 21 6 Kajari Teej, Hiroshima Day Shravana Uttara Ashadha Ashwini Punarvasu Swati 7 Heramba Sankashti Chaturthi सोम. Makara Simha Makara Karka Mesha Karka Karka Simha Tula Simha 8 Naga Panchami Subh Muhurat Krishna Paksha Pratipada Krishna Janmashtami Krishna Paksha Chaturdashi Shukla Paksha Saptami Raksha Panchami Chaitra Bhadra Bhadra 9 Balarama Jayanti, Hal Shasti Marriage: No Muhurat ४ ११ १८ २५ TUE 4 1 11 18 14 25 22 11 Krishna Janmashtami Shravana Bharani Ashlesha Vishakha Kalashtami, Kali Jayanti मंगल. Griha Pravesh: No muhurat Makara Karka Mesha Karka Karka Simha Tula Simha 13 Rohini Vrat, Gopa Navami Vehicle Purchase: 3, Krishna Paksha Dwitiya Krishna Paksha Ashtami Amavasya Radha Ashtami 15 Independence Day 6, 9, 13, 14, 16, 17, Bhadra Bhadra Bhadra Bhadra Aja Ekadashi 23, 24, 26, 30 ५ १२ १९ २६ WED 5 2 12 8 19 15 26 23 16 Pradosh Vrat, Simha Sankranti Dhanishtha Krittika Magha Anuradha 17 Masik Shivaratri बुध. -

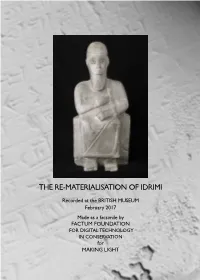

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

The Parthenon Sculptures Sarah Pepin

BRIEFING PAPER Number 02075, 9 June 2017 By John Woodhouse and Sarah Pepin The Parthenon Sculptures Contents: 1. What are the Parthenon Sculptures? 2. How did the British Museum acquire them? 3. Ongoing controversy 4. Further reading www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Parthenon Sculptures Contents Summary 3 1. What are the Parthenon Sculptures? 5 1.1 Early history 5 2. How did the British Museum acquire them? 6 3. Ongoing controversy 7 3.1 Campaign groups in the UK 9 3.2 UK Government position 10 3.3 British Museum position 11 3.4 Greek Government action 14 3.5 UNESCO mediation 14 3.6 Parliamentary interest 15 4. Further reading 20 Contributing Authors: Diana Perks Attribution: Parthenon Sculptures, British Museum by Carole Radatto. Licenced under CC BY-SA 2.0 / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 9 June 2017 Summary This paper gives an outline of the more recent history of the Parthenon sculptures, their acquisition by the British Museum and the long-running debate about suggestions they be removed from the British Museum and returned to Athens. The Parthenon sculptures consist of marble, architecture and architectural sculpture from the Parthenon in Athens, acquired by Lord Elgin between 1799 and 1810. Often referred to as both the Elgin Marbles and the Parthenon marbles, “Parthenon sculptures” is the British Museum’s preferred term.1 Lord Elgin’s authority to obtain the sculptures was the subject of a Select Committee inquiry in 1816. It found they were legitimately acquired, and Parliament then voted the funds needed for the British Museum to acquire them later that year. -

NAVRATRI 2018 ITA Invites You for Garba and Raas at Navratri

NAVRATRI 2018 ITA invites you for Garba and Raas at Navratri 2018! Dates and Venues Oct 10, 11, 15, 16, 17 & 18 : 7.30 pm - 11 pm @ICC of South Jersey Oct 14 : 7.30 pm - 11 pm @Regal Banquet Hall, 1444 Rt. 73, Pennsauken Oct 12, 20 : 7.30 pm - 12 am @Eastern H.S, 1401 Laurel Oak Rd, Voorhees Oct 13, 7.30 pm-11 pm @Moorestown H.S, 350 Bridgeboro Rd. Moorestown October 20 as Shard Purnima Garaba Celebration Pricing Free Admission for all on Monday October 15 Children 6 & under - Free College Student Special on October 20th - $5 (w/ID) Pricing at door All ages (7 & above) : Sun to Thur: $5, Fri / Sat: $10 Season Pass Adults (18-64) : $45 At Door , $40 Online (Until Oct 5) Children (7-17) / Seniors (65+): $40 At Door , $35 Online (Until Oct 5) Online season pass can be purchased until October 5th at https://www.indiatemple.org/navratri-ticket.php ********************************************************************************************* Ravan Dahan ITA Dussehra Festival on Friday October 19th 2018 from 6—10pm at ICC ITA celebrates Dussehra on Friday October 19th at 6 pm at the ICC. There will be a Musical Ramayana Play presented by Hindi USA students. Raavan Dahan Bigger and better. Food Fun for the whole family. For information contact Sangeeta Rashatwar 609-685-2755, Jagdeep Talwar 856-308-7870 Rashmi Julka 856- 873-6447 ********************************************************************************************* Spiritual Celebration Importance of Pitri-Paksha Shradha-Tarpan - Every year, an important period of 15 days (Pitru Paksha or Shraadh) is dedicated to the ancestors and forefathers. Pitru Paksha is considered perfect for performing Tarpan rituals.