Abraham and Idrimi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tayinat's Building XVI: the Religious Dimensions and Significance of A

Tayinat’s Building XVI: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua by Douglas Neal Petrovich A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Douglas Neal Petrovich, 2016 Building XVI at Tell Tayinat: The Religious Dimensions and Significance of a Tripartite Temple at Neo-Assyrian Kunulua Douglas N. Petrovich Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2016 Abstract After the collapse of the Hittite Empire and most of the power structures in the Levant at the end of the Late Bronze Age, new kingdoms and powerful city-states arose to fill the vacuum over the course of the Iron Age. One new player that surfaced on the regional scene was the Kingdom of Palistin, which was centered at Kunulua, the ancient capital that has been identified positively with the site of Tell Tayinat in the Amuq Valley. The archaeological and epigraphical evidence that has surfaced in recent years has revealed that Palistin was a formidable kingdom, with numerous cities and territories having been enveloped within its orb. Kunulua and its kingdom eventually fell prey to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which decimated the capital in 738 BC under Tiglath-pileser III. After Kunulua was rebuilt under Neo- Assyrian control, the city served as a provincial capital under Neo-Assyrian administration. Excavations of the 1930s uncovered a palatial district atop the tell, including a temple (Building II) that was adjacent to the main bit hilani palace of the king (Building I). -

Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Arnhem (nl) 2015 – 3 Anatolia in the bronze age. © Joost Blasweiler student Leiden University - [email protected] Hanigal9bat and the land Hana. From the annals of Hattusili I we know that in his 3rd year the Hurrian enemy attacked his kingdom. Thanks to the text of Hattusili I (“ruler of Kussara and (who) reign the city of Hattusa”) we can be certain that c. 60 years after the abandonment of the city of Kanesh, Hurrian armies extensively entered the kingdom of Hatti. Remarkable is that Hattusili mentioned that it was not a king or a kingdom who had attacked, but had used an expression “the Hurrian enemy”. Which might point that formerly attacks, raids or wars with Hurrians armies were known by Hattusili king of Kussara. And therefore the threatening expression had arisen in Hittite: “the Hurrian enemy”. Translation of Gary Beckman 2008, The Ancient Near East, editor Mark W. Chavalas, 220. The cuneiform texts of the annal are bilingual: Babylonian and Nesili (Hittite). Note: 16. Babylonian text: ‘the enemy from Ḫanikalbat entered my land’. The Babylonian text of the bilingual is more specific: “the enemy of Ḫanigal9 bat”. Therefore the scholar N.B. Jankowska1 thought that apparently the Hurrian kingdom Hanigalbat had existed probably from an earlier date before the reign of Hattusili i.e. before c. 1650 BC. Normally with the term Mittani one is pointing to the mighty Hurrian kingdom of the 15th century BC 2. Ignace J. Gelb reported 3 on “the dragomans of the Habigalbatian soldiers/workers” in an Old Babylonian tablet of Amisaduqa, who was a contemporary with Hattusili I. -

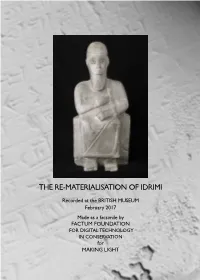

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

New Horizons in the Study of Ancient Syria

OFFPRINT FROM Volume Twenty-five NEW HORIZONS IN THE STUDY OF ANCIENT SYRIA Mark W. Chavalas John L. Hayes editors ml"ITfE ADMINISTRATION IN SYRIA IN THE LIGHT OF THE TEXTS FROM UATTUSA, UGARIT AND EMAR Gary M. Beckman Although the Hittite state of the Late Bronze Age always had its roots in central Anatolia,1 it continually sought to expand its hegemony toward the southeast into Syria, where military campaigns would bring it booty in precious metals and other goods available at home only in limited quantities, and where domination would assure the constant flow of such wealth in the fonn of tribute and imposts on the active trade of this crossroads between Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Aegean. Already in the 'seventeenth century, the Hittite kings ~attu§ili I and his adopted son and successor Mur§ili I conquered much of this area, breaking the power of the "Great Kingdom" of ~alab and even reaching distant Babylon, where the dynasty of ~ammurapi was brought to an end by Hittite attack. However, the Hittites were unable to consolidate their dominion over northern Syria and were soon forced back to the north by Hurrian princes, who were active even in eastern Anatolia.2 Practically nothing can be said concerning Hittite administration of Syria in this period, known to Hittitologists as the Old Kingdom. During the following Middle Kingdom (late sixteenth-early fourteenth centuries), Hittite power was largely confined to Anatolia, while northern Syria came under the sway 1 During the past quarter century research in Hittite studies bas proceeded at such a pace that there currently exists no adequate monographic account ofAnatolian history and culture of the second millennium. -

The Hittites United

The Major Assyrian Campaigns of 9C BCE (B S Curnock.) The Hittites United By P J Crowe Introducing a new historical framework for the Hittites - the fruits of two centuries of Anatolian archaeology A work in progress 121212 Successive generations of Near Eastern archaeologists have often had to admit that they could not reconcile their findings with the prevailing view of Hittite history. This paper is a summary version of an interim report for discussion of a new study initiated by B S Curnock. It demonstrates that the histories of the Empire and Neo-Hittites can be merged into a single integrated history of the Hatti Lands dating from the ninth to the mid-sixth centuries BCE. Interlocking supporting evidence is drawn from widespread and diverse sources including the ancient records of Assyria, Babylonia, Mitanni, Urartu, Syria, Egypt and the Old Testament. If this revision is followed, an alternative historical framework becomes available to the archaeologist within which many present difficulties of interpretation may find a more credible solution. Quote: "Few archaeologists have had the courage, or the time, or the overall knowledge to question the bases of the chronology they were taught and are using. For many, the chronological scale is only of peripheral interest...The tombstones of those rash souls who have questioned the fundamentals lie scattered along the dusty by-ways of history, forgotten and unlamented." John Dayton, 'Minerals, Metals, Glazing, and Man' (1978). Contact: Email: [email protected] Web site: www.thetroydeception.com (This version for private circulation; feedback invited.) 20 1 The Hittites United 121212 that the Hatti capital probably fell to Croesus in the time of Suppiluliumas II long before Ramesses III (perhaps the king Nectanebos whose wars are described by Diodorus Siculus) became king of Egypt. -

David J.A. Clines, "Regnal Year Reckoning in the Last Years of The

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGY REGNAL YEAR RECKONING IN THE LAST YEARS OF THE KINGDOM OF JUDAH D. J. A. CLINES Department of Biblical Studies, The University of Sheffield A long debated question in studies of the Israelite calendar and of pre-exilic chronology is: was the calendar year in Israel and Judah reckoned from the spring or the autumn? The majority verdict has come to be that throughout most of the monarchical period an autumnal calendar was employed for civil, religious, and royal purposes. Several variations on this view have been advanced. Some have thought that the spring reckoning which we find attested in the post-exilic period came into operation only during the exile, 1 but many have maintained that the usual autumnal calendar gave way in pre-exilic Judah to a spring calendar as used by Assyrians and Babylonians.2 Some have 1. So e.g. J. Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel (ET, Edinburgh, 1885, r.p. Cleveland, 1957), 108f.; K. Marti, 'Year', Encyclopaedia Biblica, iv (London, 1907), col. 5365; S. Mowinckel, 'Die Chronologie der israelitischen und jiidischen Konige', Acta Orien talia 10 (1932), 161-277 174ff.). 2. (i) In the 8th century according to E. Kutsch, Das Herbst/est ill Israel (Diss. Mainz, 1955), 68; id., RGG,3 i (1957), col. 1812; followed by H.-J. Kraus, Worship in Israel (ET, Richmond, Va., 1966), 45; similarly W. F. Albright, Bib 37 (1956), 489; A. Jepsen, Zllr Chronologie der Konige von Israel lInd Judo, in A. Jepsen and R. Hanhart, Ullter sllchllngen zur israelitisch-jiidischen Chrollologie (BZAW, 88) (Berlin, 1964), 28, 37. -

Conference Abstracts

The Object Habit conference abstracts Images and indigenous voices from the "field": museum representations of the world of Benin city and its Palace in contemporary displays of royal objects taken by British military forces in 1897 Felicity Bodenstein, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz//Max-Planck-Institut In this paper I will present some elements from a comparative study on how museums are engaging with issues surrounding restitution/repatriations demands by reformulating aspects of their narrative in the display of contested objects. I focus on Twenty-first century reinstallations of objects taken from Benin City during the British « punitive expedition » of 1897 and I examine the specific potential of the media of display in dealing with difficult aspects of a colonial legacy and its relationship to the aesthetic and cultural appreciation of these objects. In looking at these displays in a selection of the over eighty museums that hold parts of the three thousand objects dispersed in 1897, one point of interest is to consider the formulation of new narratives that essentially represent the « return » to the field that has characterised anthropological research on the Benin bronzes since the 1950s but which for a long time was not present in most museum narratives. In this presentation I will focus on how the city itself and the royal palace from which the objects were taken are represented and how this context is tied to moral questions concerning the violent appropriation processes that lead to dissemination of the brass and ivory objects from the Edo Kingdom’s Treasure. Indeed, the initial representation of Benin City as the « City of Blood » by the press and the military accounts of the Nineteenth century for a long time quite simply co-existed with the museum’s account of the artistic mastery of the Bini culture. -

January-February 2020

january-february 2020 Burying the Truth Could Egypt Fall to Iran? JERUSALEM’S ORIGINS JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2020 | VOL. 2, NO. 1 | circulation: 1,193 FROM THE EDITOR The Incredible Origins of Ancient Jerusalem 1 Burying the Truth 6 Iran to Shift Focus to Africa? 11 Could Egypt Fall to Iran? 12 INFOGRAPHIC Top 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2019 16 Archaeology Reveals Jerusalem’s Origins 22 julia goddard (cover) gary dorning (inside spread)/Watch Jerusalem Artist'sii watch rendition jerusalem of the Garden of Eden from the editor | By Gerald Flurry The Incredible Origins of Ancient Jerusalem An inspiring overview of the world’s most important and famous city he history of Jerusalem is the history of the world.” That is the opening line of “TJerusalem, an illuminating book chronicling the history of this city, written by British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore. In the introduction, Montefiore describes how absolutely central Jerusalem is in the history of human civilization, especially in the history and theology of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Using examples and anecdotes, he shows that Jerusalem has been a focal point for humanity from the beginning. He then asks this crucial question: “Of all the places in the world, why Jerusalem?” This question gets to the essence of understanding Jerusalem. Montefiore writes, “The site was remote from the trade routes of the Mediterranean coast; it was short of water, baked in the summer sun, chilled by winter winds, its jagged rocks blistered and inhospitable.” Despite these disadvantages, Jerusalem became the “center of the Earth.” Why? Anyone who is even the slightest bit familiar with the Bible knows that Jerusalem is at the heart of the biblical narrative. -

A Time to Gather Stones

A Time to Gather Stones A look at the archaeological evidences of peoples and places in the scriptures This book was put together using a number of sources, none of which I own or lay claim to. All references are available as a bibliography in the back of the book. Anything written by the author will be in Italics and used mainly to provide information not stated in the sources used. This book is not to be sold Introduction Eccl 3:1-5 ; To all there is an appointed time, even time for every purpose under the heavens, a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pull up what is planted; a time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to tear down, and a time to build up; a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to throw away stones, and a time to gather stones… Throughout the centuries since the final pages of the bible were written, civilizations have gone to ruin, libraries have been buried by sand and the foot- steps of the greatest figures of the bible seem to have been erased. Although there has always been a historical trace of biblical events left to us from early historians, it’s only been in the past 150 years with the modern science of archaeology, where a renewed interest has fueled a search and cata- log of biblical remains. Because of this, hundreds of archaeological sites and artifacts have been uncovered and although the science is new, many finds have already faded into obscurity, not known to be still existent even to the average believer. -

Egyptian Myths and Tales . JOHN A. WILSON Myths and Epics From

List of Illustrations xi Foreword • DANIEL E. FLEMING xxiii Preface to the 1975 Edition xxvii Preface to the 1958 Edition xxix Egyptian Myths and Tales . JOHN A. WILSON The Memphite Theology of Creation 1 Deliverance of Mankind from Destruction 3 The Story of Si-nuhe 5 The Story of Two Brothers 11 The Journey of Wen-Amon to Phoenicia 14 The Tradition of Seven Lean Years in Egypt 21 Myths and Epics from Mesopotamia A Sumerian Myth • S. N. KRAMER The Deluge 25 Akkadian Myths and Epics The Creation Epic (Enuma elish) • E. A. SPEISER 28 Additions to Tablet V • A, K. GRAYSON 36 The Epic of Gilgamesh • E. A. SPEISER 39 A Cosmological Incantation: The Worm and the Toothache • E. A. SPEISER 72 Adapa • E. A. SPEISER 73 Descent of Ishtar to the Nether World • E. A. SPEISER The Legend of Sargon • E. A. SPEISER 82 Nergal and Ereshkigal • A. K. GRAYSON 83 The Myth of Zu (Anzu) • A. K. GRAYSON 92 A Babylonian Theogony • A. K. GRAYSON 99 Hittite Myths • ALBRECHT GOETZE The Telepinus Myth 101 El, Ashertu, and the Storm-god (Elkunirsha andAshertu) 105 Ugaritic Myths and Epics • H. L. GINSBERG Poems about Baal and Anath (The Baal Cycle) 107 The Tale of Aqhat 134 Legal Texts Collections of Laws from Mesopotamia The Laws of Eshnunna • ALBRECHT GOETZE 150 The Code of Hammurabi • THÉOPHILE J. MEEK 155 The Laws of Ur-Nammu • J. J. FINKELSTEIN 179 Sumerian Laws • J. J. FINKELSTEIN 182 The Edict of Ammisaduqa • J. J. FINKELSTEIN 183 Documents from the Practice of Law Mesopotamian Legal Documents • THÉOPHILE J. -

Yamhad Kiralliği1

YAMHAD KIRALLIĞI1 Prof. Dr. Füruzan KINAL M.Ö. II. Binyıl eski Önasya tarihi denilebilir ki, münhasıran kuzey Suriye etrafında dolanır. Bu da pek tabiidir, zira eski Önasya memleket- lerini teşkil eden Mısır, Mezopotamya ve Anadolu toprakları arasındaki irtibat ancak ve yalnız kuzey Suriye aracılığı ile mümkün olabiliyordu. Esasen M.Ö. II. Binyılm ilk yarısında bütün münakalat kara yollarıyle yapılıyordu. Bu yolların başlıcası İskenderun körfezini (O zamanlar bu rolü Ugarit şehri yapıyordu) Basra körfezine bağlıyan Fırat nehri mecra- sının meydana getirdiği tabii yoldu, bu yol eski Meskene (Emar) ye ulaştıktan sonra kuzey, güney ve batı istikametinde ayrılıyordu. Güney yolu üzerindeki ilk mühim ticaret merkezi Halep şehri idi. Ha- lepten sonra bu yol Filistin-Suriye sahil şeridi ile Mısıra kadar uzanı- yordu. Böylece Anadolu ile Mısır arasında işliyen kervan yolu gibi, Mezopotamya-Mısır arasındaki yol da mutlaka Halep şehrine uğramak zorunda idi. Kuzey Suriyenin M.Ö. II. Binyıl tarihindeki öneminin ikinci bir sebebi de Mezopotamya ve Mısır gibi o zamanların ileri medeniyet merkezlerinin, Lübnan dağlarında yetişen kıymetli ağaçların tomruk- larına olan şiddetli ihtiyaçları idi. Mısır Firavunları muhteşem saray- larını, mabedlerini ve ehramlarını yaptırabilmek için, kuzey Suriye memleketlerinden sedr, servi v.s. tomrukları getirttikleri gibi, Babil ve Asur kıralları da taştan ve ormandan mahrum olan Mezopotamya- da Lübnanların "Sedr ormanlarına" mühtaç idiler. Bu yüzdendir ki Agadeli Sargon zamanından beri Lübnanlar üzerindeki Sedr orman- larından (Amanoslardan) ve Gümüş dağlarından (Toroslardan) bah- sedilmektedir 2. Bu coğrafi şartların doğurduğu ekonomik amiller sebebile M.Ö. II. Binyıl boyunca kuzey Suriye toprakları Mısır, Mezopotamya ve 1 ,G. Dossiıı, in "Le royaume d'Alep au XVIII e siecle avant nötre ere d'apres Ies Archives royales de Mari" adlı makalesini malesef elde edemedik.