Military at Emar-VII Inglés

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Hittite “Royal Guard” During the Old Kingdom: Observations on Elite Military Units and Their Possible Warfare Applications

Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies - Volume 7, Issue 3, July 2021 – Pages 171-186 The “Protocols” for the Hittite “Royal Guard” during the Old Kingdom: Observations on Elite Military Units and their Possible Warfare Applications By Eduardo Ferreira* In this article, we intend to analyse the importance and modus operandi of a military unit (generally known as “Royal Guard”) whose function was, among other things, the protection of the Hattuša-based Hittite kings. For this essay, we will be mainly using two Hittite textual sources known as “instructions” or “protocols”. We aim to find a connection between these guards and their function regarding the protection of the royal palace as well as their military enlistment in that elite unit. The period to be covered in this analysis comes directly from the choice of sources: the Hittite Old Kingdom, confined between the chronological beacons of the 17th, 16th and 15th centuries BC. With this analysis, we intend to provide some relevant data that may contribute to a better understanding of these elite military units, particularly in regards to their probable warfare functions. Were they used in battle? How were they armed? What was their tactical importance in combat? How was the recruitment done? How were the units formed? These will be some questions that we will try to answer throughout this article. Keywords: guard, palace, command, warfare, infantry Introduction The Hittites were an Indo-European people that arrived in Anatolia through the Caucasus from Eurasia between 2000 and 1900 BC (Haywood 2005, Bryce 2005). On their Indo-European journey to the west, they also brought horses (Raulwing 2000, Renfrew 1990, Joseph and Fritz 2017/2018). -

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

Fighting with and Against Napoleon: the Memoirs of Jan Willem Van Wetering

The Napoleon Series Fighting with and against Napoleon: The Memoirs of Jan Willem van Wetering Translated and edited by: Marc Schaftenaar JAN WILLEM VAN WETERING (born in Zwolle, 15 September 1789 – died in Zwolle, 1 February 1859) was only 14 years old when he joined the army of the Batavian Republic. He retired from the army in 1848, after a long and distinguished career. Even at 14 he was quite tall, being immediately made a soldier instead of a drummer; he is soon transferred to the grenadier company, and he remains a grenadier during his active service. Throughout the memoir, one finds that Van Wetering was a fine soldier, who not only did his duty, but also took good care of those he commanded, though he never boasts about his actions. Company commanders offer him a place in their companies, and one even goes as far as to trick him into a bar fight, in order to tarnish his reputation and prevent him from being transferred to the Guard Grenadiers, -although he later is still invited to join the Guard. His memoirs are however still full of details such as descriptions of the routes, with distances (in hours) and dates of the marches. He added more information, like an order of battle for the Netherlands army at Waterloo, or a list of names of the Dutch soldiers who returned with the Russo-German Legion. The hardships he suffers during the campaign in Russia and life as a prisoner of war are the greatest part of this memoir, and it is only too bad he only give as minimal account of his service in the Russo-German Legion. -

Battle of the Mincio River

Battle of the Mincio River Age of Eagles Scenario by GRW, 2008 SETTING Date: 8 February 1814, 10:00 AM Location: 10 miles south of Lake Garda, Italy Combatants: French Empire & Kingdom of Italy vs. Austria History: As Napoleon retreated behind the Rhine River following a crushing defeat at Leipzig, the Sixth Coalition pressed their advance on other fronts. In northern Italy, a veteran Austrian army of 35,000 men under Field Marshal Heinrich von Bellegarde sought to reestablish Austrian dominance over Italy. A major victory would enable the Austrians to link up with the recent defector and King of Naples, Joachim Murat. Standing between these two forces was a conscript army of 34,000 men commanded by Napoleon’s stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais. Eugene sought to attack and destroy the Austrian field army before dealing with Murat’s Neapolitans, and toward this end, he intended to quickly concrete his scattered divisions on the east bank of the Mincio River, near the town of Villafranca. Unbeknownst to the French, the Austrian army was not concentrated near Villafranca. Field Marshal Bellegarde mistakenly believed the French were retreating to the west, and had begun to send his divisions across the Mincio River in pursuit. When February 8, 1814 dawned, both armies straddled the river at different points, and neither commander realized the intentions of the other. Eugene de Beauharnais Heinrich von Bellegarde French Orders: Trap and Austrian Orders: Locate destroy the Austrian army and engage the French along the banks of the rearguard. Control all Mincio River. Keep control roads leading east to of the vital bridge at Goito. -

New Horizons in the Study of Ancient Syria

OFFPRINT FROM Volume Twenty-five NEW HORIZONS IN THE STUDY OF ANCIENT SYRIA Mark W. Chavalas John L. Hayes editors ml"ITfE ADMINISTRATION IN SYRIA IN THE LIGHT OF THE TEXTS FROM UATTUSA, UGARIT AND EMAR Gary M. Beckman Although the Hittite state of the Late Bronze Age always had its roots in central Anatolia,1 it continually sought to expand its hegemony toward the southeast into Syria, where military campaigns would bring it booty in precious metals and other goods available at home only in limited quantities, and where domination would assure the constant flow of such wealth in the fonn of tribute and imposts on the active trade of this crossroads between Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Aegean. Already in the 'seventeenth century, the Hittite kings ~attu§ili I and his adopted son and successor Mur§ili I conquered much of this area, breaking the power of the "Great Kingdom" of ~alab and even reaching distant Babylon, where the dynasty of ~ammurapi was brought to an end by Hittite attack. However, the Hittites were unable to consolidate their dominion over northern Syria and were soon forced back to the north by Hurrian princes, who were active even in eastern Anatolia.2 Practically nothing can be said concerning Hittite administration of Syria in this period, known to Hittitologists as the Old Kingdom. During the following Middle Kingdom (late sixteenth-early fourteenth centuries), Hittite power was largely confined to Anatolia, while northern Syria came under the sway 1 During the past quarter century research in Hittite studies bas proceeded at such a pace that there currently exists no adequate monographic account ofAnatolian history and culture of the second millennium. -

David J.A. Clines, "Regnal Year Reckoning in the Last Years of The

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGY REGNAL YEAR RECKONING IN THE LAST YEARS OF THE KINGDOM OF JUDAH D. J. A. CLINES Department of Biblical Studies, The University of Sheffield A long debated question in studies of the Israelite calendar and of pre-exilic chronology is: was the calendar year in Israel and Judah reckoned from the spring or the autumn? The majority verdict has come to be that throughout most of the monarchical period an autumnal calendar was employed for civil, religious, and royal purposes. Several variations on this view have been advanced. Some have thought that the spring reckoning which we find attested in the post-exilic period came into operation only during the exile, 1 but many have maintained that the usual autumnal calendar gave way in pre-exilic Judah to a spring calendar as used by Assyrians and Babylonians.2 Some have 1. So e.g. J. Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel (ET, Edinburgh, 1885, r.p. Cleveland, 1957), 108f.; K. Marti, 'Year', Encyclopaedia Biblica, iv (London, 1907), col. 5365; S. Mowinckel, 'Die Chronologie der israelitischen und jiidischen Konige', Acta Orien talia 10 (1932), 161-277 174ff.). 2. (i) In the 8th century according to E. Kutsch, Das Herbst/est ill Israel (Diss. Mainz, 1955), 68; id., RGG,3 i (1957), col. 1812; followed by H.-J. Kraus, Worship in Israel (ET, Richmond, Va., 1966), 45; similarly W. F. Albright, Bib 37 (1956), 489; A. Jepsen, Zllr Chronologie der Konige von Israel lInd Judo, in A. Jepsen and R. Hanhart, Ullter sllchllngen zur israelitisch-jiidischen Chrollologie (BZAW, 88) (Berlin, 1964), 28, 37. -

Dutch Military Power at the Time of the Early Bakufu Army, 1861-1864

Title Dutch Military Power at the Time of the Early Bakufu Army, 1861-1864 Author(s) Bara, Xavier Citation 国際公共政策研究. 16(1) P.295-P.307 Issue Date 2011-09 Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/11094/23027 DOI rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University 295 Dutch Military Power at the Time of the Early Bakufu Army, 1861-1864 BARA Xavier * Abstract During the Bunkyū Era (1861-1864), the Tokugawa Bakufu created its fi rst regular army, while the Kingdom of the Netherlands was its main provider of Western military science. Consequently, the bakufu army was formed according to a new model that introduced regulations and equipment of Dutch origins. However, what was the real military power of the Netherlands behind this Dutch primacy in Japan? The article presents an overview of the Dutch defences and army in the early 1860s, in order to evaluate the gap between the Dutch military infl uence in Japan and the Dutch military power in Europe. Keywords: Royal Dutch Army, Belgian secession, middle power, fortifi cations, Prussian-Dutch entente * Belgian Doctoral Student (University of Liège), Research Student (Osaka University), and Reserve Second Lieutenant (Belgian Army, Horse-Jagers), the author is a military historian and experimental archaeologist specialized in the armies of the Austro-Prussian rivalry be- tween 1848 and 1866, and in their infl uence in some other armies of the same period, including the Dutch army. 296 国際公共政策研究 第16巻第1号 Introduction In 1862, the bakufu army was established by the Bunkyū Reforms, in order to revive the shogunal power of the Tokugawa. -

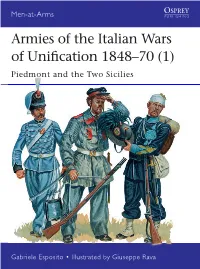

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

“The Sherden in His Majesty's Captivity”: a Comparative Look At

1 “The Sherden in His Majesty’s Captivity”: A Comparative Look at the Mercenaries of New Kingdom Egypt Jordan Snowden Rhodes College Honors History Word Count (including citations and bibliography): 38098 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 Chapter 1: How They Were Recruited---------------------------------------------------------------------6 Chapter 2: How They Fought------------------------------------------------------------------------------36 Chapter 3: How They Were Paid and Settled------------------------------------------------------------80 Conclusion: How They Were Integrated----------------------------------------------------------------103 Bibliography------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------125 2 Introduction Mercenary troops have been used by numerous states throughout history to supplement their native armies with skilled foreign soldiers – Nepali Gurkhas have served with distinction in the armies of India and the United Kingdom for well over a century, Hessians fought for Great Britain during the American Revolution, and even the Roman Empire supplemented its legions with foreign “auxiliary” units. Perhaps the oldest known use of mercenaries dates to the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt (1550-1069 BCE). New Kingdom Egypt was a powerful military empire that had conquered large parts of Syria, all of Palestine, and most of Nubia (today northern Sudan). Egyptian pharaohs of this period were truly -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process. -

A Political History of the Arameans

A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE ARAMEANS Press SBL ARCHAEOLOGY AND BIBLICAL STUDIES Brian B. Schmidt, General Editor Editorial Board: Aaron Brody Annie Caubet Billie Jean Collins Israel Finkelstein André Lemaire Amihai Mazar Herbert Niehr Christoph Uehlinger Number 13 Press SBL A POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE ARAMEANS From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities K. Lawson Younger Jr. Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2016 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and record- ing, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Younger, K. Lawson. A political history of the Arameans : from their origins to the end of their polities / K. Lawson Younger, Jr. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical literature archaeology and Biblical studies ; number 13) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-128-5 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837- 080-5 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837-084-3 (electronic format) 1. Arameans—History. 2. Arameans—Politics and government. 3. Middle East—Politics and government. I. Title. DS59.A7Y68 2015 939.4'3402—dc23 2015004298 Press Printed on acid-free paper. SBL To Alan Millard, ֲאַרִּמֹי אֵבד a pursuer of a knowledge and understanding of Press SBL Press SBL CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... -

The Secret Serbian-Bulgarian Treaty of Alliance of 1904 and the Russian Policy in the Balkans Before the Bosnian Crisis

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2007 The Secret Serbian-Bulgarian Treaty of Alliance of 1904 and the Russian Policy in the Balkans Before the Bosnian Crisis Kiril Valtchev Merjanski Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Merjanski, Kiril Valtchev, "The Secret Serbian-Bulgarian Treaty of Alliance of 1904 and the Russian Policy in the Balkans Before the Bosnian Crisis" (2007). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 96. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/96 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SECRET SERBIAN-BULGARIAN TREATY OF ALLIANCE OF 1904 AND THE RUSSIAN POLICY IN THE BALKANS BEFORE THE BOSNIAN CRISIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KIRIL VALTCHEV MERJANSKI M.A., Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Bulgaria 2007 Wright State University COPYRIGHT BY KIRIL VALTCHEV MERJANSKI 2006 WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES Winter Quarter 2007 I hereby recommend that the thesis prepared under my supervision by KIRIL VALTCHEV MERJANSKI entitled THE SECRET SERBIAN-BULGARIAN TREATY OF ALLIANCE OF 1904 AND THE RUSSIAN POLICY IN THE BALKANS BEFORE THE BOSNIAN CRISIS be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS.