Fighting with and Against Napoleon: the Memoirs of Jan Willem Van Wetering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Hittite “Royal Guard” During the Old Kingdom: Observations on Elite Military Units and Their Possible Warfare Applications

Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies - Volume 7, Issue 3, July 2021 – Pages 171-186 The “Protocols” for the Hittite “Royal Guard” during the Old Kingdom: Observations on Elite Military Units and their Possible Warfare Applications By Eduardo Ferreira* In this article, we intend to analyse the importance and modus operandi of a military unit (generally known as “Royal Guard”) whose function was, among other things, the protection of the Hattuša-based Hittite kings. For this essay, we will be mainly using two Hittite textual sources known as “instructions” or “protocols”. We aim to find a connection between these guards and their function regarding the protection of the royal palace as well as their military enlistment in that elite unit. The period to be covered in this analysis comes directly from the choice of sources: the Hittite Old Kingdom, confined between the chronological beacons of the 17th, 16th and 15th centuries BC. With this analysis, we intend to provide some relevant data that may contribute to a better understanding of these elite military units, particularly in regards to their probable warfare functions. Were they used in battle? How were they armed? What was their tactical importance in combat? How was the recruitment done? How were the units formed? These will be some questions that we will try to answer throughout this article. Keywords: guard, palace, command, warfare, infantry Introduction The Hittites were an Indo-European people that arrived in Anatolia through the Caucasus from Eurasia between 2000 and 1900 BC (Haywood 2005, Bryce 2005). On their Indo-European journey to the west, they also brought horses (Raulwing 2000, Renfrew 1990, Joseph and Fritz 2017/2018). -

Military Tribunal, Indictments

MILITARY TRIBUNALS Case No. 12 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -against- WILHELM' VON LEEB, HUGO SPERRLE, GEORG KARL FRIEDRICH-WILHELM VON KUECHLER, JOHANNES BLASKOWITZ, HERMANN HOTH, HANS REINHARDT. HANS VON SALMUTH, KARL HOL LIDT, .OTTO SCHNmWIND,. KARL VON ROQUES, HERMANN REINECKE., WALTERWARLIMONT, OTTO WOEHLER;. and RUDOLF LEHMANN. Defendants OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (US) NORNBERG 1947 • PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ TABLE OF CONTENTS - Page INTRODUCTORY 1 COUNT ONE-CRIMES AGAINST PEACE 6 A Austria 'and Czechoslovakia 7 B. Poland, France and The United Kingdom 9 C. Denmark and Norway 10 D. Belgium, The Netherland.; and Luxembourg 11 E. Yugoslavia and Greece 14 F. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 17 G. The United states of America 20 . , COUNT TWO-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST ENEMY BELLIGERENTS AND PRISONERS OF WAR 21 A: The "Commissar" Order , 22 B. The "Commando" Order . 23 C, Prohibited Labor of Prisoners of Wal 24 D. Murder and III Treatment of Prisoners of War 25 . COUNT THREE-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST CIVILIANS 27 A Deportation and Enslavement of Civilians . 29 B. Plunder of Public and Private Property, Wanton Destruc tion, and Devastation not Justified by Military Necessity. 31 C. Murder, III Treatment and Persecution 'of Civilian Popu- lations . 32 COUNT FOUR-COMMON PLAN OR CONSPIRACY 39 APPENDIX A-STATEMENT OF MILITARY POSITIONS HELD BY THE DEFENDANTS AND CO-PARTICIPANTS 40 2 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ INDICTMENT -

Republic of Violence: the German Army and Politics, 1918-1923

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-09-11 Republic of Violence: The German Army and Politics, 1918-1923 Bucholtz, Matthew N Bucholtz, M. N. (2015). Republic of Violence: The German Army and Politics, 1918-1923 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27638 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2451 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Republic of Violence: The German Army and Politics, 1918-1923 By Matthew N. Bucholtz A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2015 © Matthew Bucholtz 2015 Abstract November 1918 did not bring peace to Germany. Although the First World War was over, Germany began a new and violent chapter as an outbreak of civil war threatened to tear the country apart. The birth of the Weimar Republic, Germany’s first democratic government, did not begin smoothly as republican institutions failed to re-establish centralized political and military authority in the wake of the collapse of the imperial regime. Coupled with painful aftershocks from defeat in the Great War, the immediate postwar era had only one consistent force shaping and guiding political and cultural life: violence. -

Battle of the Mincio River

Battle of the Mincio River Age of Eagles Scenario by GRW, 2008 SETTING Date: 8 February 1814, 10:00 AM Location: 10 miles south of Lake Garda, Italy Combatants: French Empire & Kingdom of Italy vs. Austria History: As Napoleon retreated behind the Rhine River following a crushing defeat at Leipzig, the Sixth Coalition pressed their advance on other fronts. In northern Italy, a veteran Austrian army of 35,000 men under Field Marshal Heinrich von Bellegarde sought to reestablish Austrian dominance over Italy. A major victory would enable the Austrians to link up with the recent defector and King of Naples, Joachim Murat. Standing between these two forces was a conscript army of 34,000 men commanded by Napoleon’s stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais. Eugene sought to attack and destroy the Austrian field army before dealing with Murat’s Neapolitans, and toward this end, he intended to quickly concrete his scattered divisions on the east bank of the Mincio River, near the town of Villafranca. Unbeknownst to the French, the Austrian army was not concentrated near Villafranca. Field Marshal Bellegarde mistakenly believed the French were retreating to the west, and had begun to send his divisions across the Mincio River in pursuit. When February 8, 1814 dawned, both armies straddled the river at different points, and neither commander realized the intentions of the other. Eugene de Beauharnais Heinrich von Bellegarde French Orders: Trap and Austrian Orders: Locate destroy the Austrian army and engage the French along the banks of the rearguard. Control all Mincio River. Keep control roads leading east to of the vital bridge at Goito. -

US and NATO Military Planning on Mission of V Corps/US Army During Crises and in Wartime,' (Excerpt)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified December 16, 1982 East German Ministry of State Security, 'US and NATO Military Planning on Mission of V Corps/US Army During Crises and in Wartime,' (excerpt) Citation: “East German Ministry of State Security, 'US and NATO Military Planning on Mission of V Corps/US Army During Crises and in Wartime,' (excerpt),” December 16, 1982, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, BStU, Berlin, ZA, HVA, 19, pp. 126-359. Translated from German by Bernd Schaefer; available in original language at the Parallel History Project. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112680 Summary: The Stasi's own preface to the V Corps/U.S. Army 1981 war plan (which recognizes that NATO's concept was defensive in nature in contrast to Warsaw Pact plans, which until 1987 indeed envisioned the mentioned "breakthrough towards the Rhine") Original Language: German Contents: English Translation MINISTRY FOR STATE SECURITY Top Secret! Berlin, 16. Dec 1982 Only for personal use! Nr. 626/82 Return is requested! Expl. 5. Bl. MY Information about Military planning of the USA and NATO for the operation of the V. Army Corps/USA in times of tension and in war Part 1 Preliminary Remarks Through reliable intelligence we received portions of the US and NATO military crisis and wartime planning for the deployment of the V Corps/USA stationed in the FRG. This intelligence concerns the secret Operations Plan 33001 (GDP – General Defense Plan) for the V Corps/USA in Europe. The plan is endorsed by the US Department of the Army and, after consultation with NATO, became part of NATO planning. -

Polish Battles and Campaigns in 13Th–19Th Centuries

POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 Scientific editors: Ph. D. Grzegorz Jasiński, Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Reviewers: Ph. D. hab. Marek Dutkiewicz, Ph. D. hab. Halina Łach Scientific Council: Prof. Piotr Matusak – chairman Prof. Tadeusz Panecki – vice-chairman Prof. Adam Dobroński Ph. D. Janusz Gmitruk Prof. Danuta Kisielewicz Prof. Antoni Komorowski Col. Prof. Dariusz S. Kozerawski Prof. Mirosław Nagielski Prof. Zbigniew Pilarczyk Ph. D. hab. Dariusz Radziwiłłowicz Prof. Waldemar Rezmer Ph. D. hab. Aleksandra Skrabacz Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Prof. Lech Wyszczelski Sketch maps: Jan Rutkowski Design and layout: Janusz Świnarski Front cover: Battle against Theutonic Knights, XVI century drawing from Marcin Bielski’s Kronika Polski Translation: Summalinguæ © Copyright by Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, 2016 © Copyright by Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości, 2016 ISBN 978-83-65409-12-6 Publisher: Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości Contents 7 Introduction Karol Olejnik 9 The Mongol Invasion of Poland in 1241 and the battle of Legnica Karol Olejnik 17 ‘The Great War’ of 1409–1410 and the Battle of Grunwald Zbigniew Grabowski 29 The Battle of Ukmergė, the 1st of September 1435 Marek Plewczyński 41 The -

Dutch Military Power at the Time of the Early Bakufu Army, 1861-1864

Title Dutch Military Power at the Time of the Early Bakufu Army, 1861-1864 Author(s) Bara, Xavier Citation 国際公共政策研究. 16(1) P.295-P.307 Issue Date 2011-09 Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/11094/23027 DOI rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University 295 Dutch Military Power at the Time of the Early Bakufu Army, 1861-1864 BARA Xavier * Abstract During the Bunkyū Era (1861-1864), the Tokugawa Bakufu created its fi rst regular army, while the Kingdom of the Netherlands was its main provider of Western military science. Consequently, the bakufu army was formed according to a new model that introduced regulations and equipment of Dutch origins. However, what was the real military power of the Netherlands behind this Dutch primacy in Japan? The article presents an overview of the Dutch defences and army in the early 1860s, in order to evaluate the gap between the Dutch military infl uence in Japan and the Dutch military power in Europe. Keywords: Royal Dutch Army, Belgian secession, middle power, fortifi cations, Prussian-Dutch entente * Belgian Doctoral Student (University of Liège), Research Student (Osaka University), and Reserve Second Lieutenant (Belgian Army, Horse-Jagers), the author is a military historian and experimental archaeologist specialized in the armies of the Austro-Prussian rivalry be- tween 1848 and 1866, and in their infl uence in some other armies of the same period, including the Dutch army. 296 国際公共政策研究 第16巻第1号 Introduction In 1862, the bakufu army was established by the Bunkyū Reforms, in order to revive the shogunal power of the Tokugawa. -

The German Military Mission to Romania, 1940-1941 by Richard L. Dinardo

The German Military Mission to Romania, 1940–1941 By RICHARD L. Di NARDO hen one thinks of security assistance and the train- ing of foreign troops, W Adolf Hitler’s Germany is not a country that typically comes to mind. Yet there were two instances in World War II when Germany did indeed deploy troops to other countries that were in noncombat cir- cumstances. The countries in question were Finland and Romania, and the German mili- tary mission to Romania is the subject of this article. The activities of the German mission to Romania are discussed and analyzed, and some conclusions and hopefully a few take- aways are offered that could be relevant for military professionals today. Creation of the Mission The matter of how the German military mission to Romania came into being can be covered relatively quickly. In late June 1940, the Soviet Union demanded from Romania the cession of both Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. The only advice Germany could give to the Romanian government was to agree to surrender the territory.1 Fearful of further Soviet encroachments, the Roma- nian government made a series of pleas to Germany including a personal appeal from Wikimedia Commons King Carol II to Hitler for German military assistance in the summer of 1940. Hitler, Finnish Volunteer Battalion of German Waffen-SS return home from front in 1943 however, was not yet willing to undertake such a step. Thus, all Romanian requests were rebuffed with Hitler telling Carol that Romania brought its own problems upon itself by its prior pro-Allied policy. -

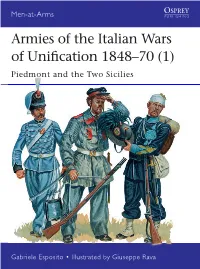

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

“The Sherden in His Majesty's Captivity”: a Comparative Look At

1 “The Sherden in His Majesty’s Captivity”: A Comparative Look at the Mercenaries of New Kingdom Egypt Jordan Snowden Rhodes College Honors History Word Count (including citations and bibliography): 38098 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 Chapter 1: How They Were Recruited---------------------------------------------------------------------6 Chapter 2: How They Fought------------------------------------------------------------------------------36 Chapter 3: How They Were Paid and Settled------------------------------------------------------------80 Conclusion: How They Were Integrated----------------------------------------------------------------103 Bibliography------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------125 2 Introduction Mercenary troops have been used by numerous states throughout history to supplement their native armies with skilled foreign soldiers – Nepali Gurkhas have served with distinction in the armies of India and the United Kingdom for well over a century, Hessians fought for Great Britain during the American Revolution, and even the Roman Empire supplemented its legions with foreign “auxiliary” units. Perhaps the oldest known use of mercenaries dates to the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt (1550-1069 BCE). New Kingdom Egypt was a powerful military empire that had conquered large parts of Syria, all of Palestine, and most of Nubia (today northern Sudan). Egyptian pharaohs of this period were truly -

The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815

Men-at-Arms The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815 1FUFS)PGTDISÕFSr*MMVTUSBUFECZ(FSSZ&NCMFUPO © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Men-at-Arms . 496 The Prussian Army of the Lower Rhine 1815 Peter Hofschröer . Illustrated by Gerry Embleton Series editor Martin Windrow © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com THE PRUSSIAN ARMY OF THE LOWER RHINE 1815 INTRODUCTION n the aftermath of Napoleon’s first abdication in April 1814, the European nations that sent delegations to the Congress of Vienna in INovember were exhausted after a generation of almost incessant warfare, but still determined to pursue their own interests. The unity they had achieved to depose their common enemy now threatened to dissolve amid old rivalries as they argued stubbornly over the division of the territorial spoils of victory. Britain, the paymaster of so many alliances against France, saw to it that the Low Countries were united, albeit uncomfortably (and fairly briefly), into a single Kingdom of the Netherlands, but otherwise remained largely aloof from this bickering. Having defeated its main rival for a colonial empire, it could now rule A suitably classical portrait the waves unhindered; its only interest in mainland Europe was to ensure drawing of Napoleon’s nemesis: a stable balance of power, and peace in the markets that it supplied with General Field Marshal Gebhard, Prince Blücher von Wahlstatt both the fruits of global trading and its manufactured goods. (1742–1819), the nominal C-in-C At Vienna a new fault-line opened up between other former allies. of the Army of the Lower Rhine. The German War of Liberation in 1813, led by Prussia, had been made Infantry Gen Friedrich, Count possible by Prussia’s persuading of Russia to continue its advance into Kleist von Nollendorf was the Central Europe after driving the wreckage of Napoleon’s Grande Armée original commander, but was replaced with the 72-year-old back into Poland. -

Patton and Logistics of the Third Army

Document created: 20 March 03 Logistics and Patton’s Third Army Lessons for Today’s Logisticians Maj Jeffrey W. Decker Preface When conducting serious study of any operational campaign during World War II, the military student quickly realizes the central role logistics played in the overall war effort. Studying the operations of General George S. Patton and his Third United States Army during 1944-45 provides all members of the profession of arms—especially the joint logistician—valuable lessons in the art and science of logistics during hostilities. Future conflicts will not provide a two or three year "trial and error" logistics learning curve; rather, the existing sustainment infrastructure and its accompanying logisticians are what America’s armed forces will depend on when the fighting begins. My sincere thanks to Dr. Richard R. Muller for his guiding assistance completing this project. I also want to thank the United States Army Center of Military History for providing copies of the United States Army in World War II official histories and Lt Col (S) Clete Knaub for his editing advice and counsel. Finally, thanks go to my wife Misty for her support writing this paper; her grandfather, Mark Novick for his wisdom and guidance during the preparation of this project; and to his brother David, a veteran of the Third United States Army. I dedicate this project to him. Abstract George S. Patton and his Third Army waged a significant combined arms campaign on the Western Front during 1944-45. Both his military leadership and logistics acumen proved decisive against enemy forces from North Africa to the Rhine River.