CANAAN Son of Ham, Grandson of Noah, Who Laid a Curse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 BC

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 81, 2015, pp. 361–392 © The Prehistoric Society doi:10.1017/ppr.2015.17 Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 BC By KRISTIAN KRISTIANSEN1 and PAULINA SUCHOWSKA-DUCKE2 The Bronze Age was the first epoch in which societies became irreversibly linked in their co-dependence on ores and metallurgical skills that were unevenly distributed in geographical space. Access to these critical resources was secured not only via long-distance physical trade routes, making use of landscape features such as river networks, as well as built roads, but also by creating immaterial social networks, consisting of interpersonal relations and diplomatic alliances, established and maintained through the exchange of extraordinary objects (gifts). In this article, we reason about Bronze Age communication networks and apply the results of use-wear analysis to create robust indicators of the rise and fall of political and commercial networks. In conclusion, we discuss some of the historical forces behind the phenomena and processes observable in the archaeological record of the Bronze Age in Europe and beyond. Keywords: Bronze Age communication networks, agents, temperate Europe, Mediterranean Basin THE EUROPEAN BRONZE AGE AS A COMMUNICATION by small variations in ornaments and weapons NETWORK: HISTORICAL & THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK (Kristiansen 2014). Among the characteristics that might compel archaeo- Initially driven by the necessity to gain access to logists to label the Bronze Age a ‘formative epoch’ in remote resources and technological skills, Bronze Age European history, the density and extent of the era’s societies established communication links that ranged exchange and communication networks should per- from the Baltic to the Mediterranean and from haps be regarded as the most significant. -

Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Arnhem (nl) 2015 – 3 Anatolia in the bronze age. © Joost Blasweiler student Leiden University - [email protected] Hanigal9bat and the land Hana. From the annals of Hattusili I we know that in his 3rd year the Hurrian enemy attacked his kingdom. Thanks to the text of Hattusili I (“ruler of Kussara and (who) reign the city of Hattusa”) we can be certain that c. 60 years after the abandonment of the city of Kanesh, Hurrian armies extensively entered the kingdom of Hatti. Remarkable is that Hattusili mentioned that it was not a king or a kingdom who had attacked, but had used an expression “the Hurrian enemy”. Which might point that formerly attacks, raids or wars with Hurrians armies were known by Hattusili king of Kussara. And therefore the threatening expression had arisen in Hittite: “the Hurrian enemy”. Translation of Gary Beckman 2008, The Ancient Near East, editor Mark W. Chavalas, 220. The cuneiform texts of the annal are bilingual: Babylonian and Nesili (Hittite). Note: 16. Babylonian text: ‘the enemy from Ḫanikalbat entered my land’. The Babylonian text of the bilingual is more specific: “the enemy of Ḫanigal9 bat”. Therefore the scholar N.B. Jankowska1 thought that apparently the Hurrian kingdom Hanigalbat had existed probably from an earlier date before the reign of Hattusili i.e. before c. 1650 BC. Normally with the term Mittani one is pointing to the mighty Hurrian kingdom of the 15th century BC 2. Ignace J. Gelb reported 3 on “the dragomans of the Habigalbatian soldiers/workers” in an Old Babylonian tablet of Amisaduqa, who was a contemporary with Hattusili I. -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

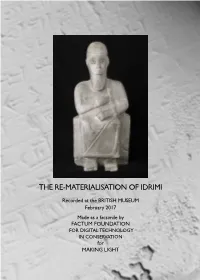

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

PLATE I . Jug of the 15Th Century B.C. from Kourion UNIVERSITY MUSEUM BULLETIN VOL

• PLATE I . Jug of the 15th Century B.C. from Kourion UNIVERSITY MUSEUM BULLETIN VOL . 8 JANUARY. 1940 N o. l THE ACHAEANS AT KOURION T HE University Museum has played a distinguished part in the redis- covery of the pre-Hellenic civilization of Greece. The Heroic Age de- scribed by Homer was first shown to have a basis in fact by Schliemann's excavations at Troy in 1871, and somewhat later at Mycenae and Tiryns, and by Evans' discovery of the palace of King Minos at Knossos in Crete. When the first wild enthusiasm blew itself out it became apparent that many problems raised by this newly discovered civilization were not solved by the first spectacular finds. In the period of careful excavation and sober consideration of evidence which followed, the University Mu- seum had an important part. Its expeditions to various East Cretan sites did much lo put Cretan archaeology on the firm foundation it now enjoys. Alter the excavations at Vrokastro in East Crete in 1912 the efforts of the Museum were directed to other lands. It was only in 1931, when an e xpedition under the direction of Dr. B. H. Hill excavated at Lapithos in Cyprus, that the University Museum re-entered the early Greek field. The Cyprus expedition was recompcsed in 1934, still under the direc- tion of Dr. Hill, with the assistance of Mr. George H. McFadden and the writer, and began work at its present site, ancient Kourion. Kourion was 3 in classical times lhe capital of cne of the independent kingdoms of Cyprus, and was traditionally Greek. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

"A Collaborative Study of Early Glassmaking in Egypt C. 1500 BC." Annales Du 13E Congrès De L’Association Internationale Pour L’Histoire Du Verre

Lilyquist, C.; Brill, R. H. "A Collaborative Study of Early Glassmaking in Egypt c. 1500 BC." Annales du 13e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre. Lochem, the Netherlands: AIHV, 1996, pp. 1-9. © 1996, Lochem AIHV. Used with permission. A collaborative study of early glassmaking in Egypt c. 1500 BC C. Lilyquist and R. H. Brill Our study of early glass was begun when we discovered that Metropolitan Museum objects from the tomb of three foreign wives of Tuthmosis I11 in the Wadi Qirud at Luxor had many more vitreous items than had been thought during the last 60 years. Not only was there a glass lotiform vessel (fig. 34)', but two glassy vessels (fig. lo), and many beads and a great amount of inlay of glass (figs. 36-40). As it became apparent that half of the inlays had been colored by cobalt (that rare metal whose provenance in the 2nd millennium BC is still a mystery), and when the primary author realized that most of the Egyptian glass studies published up to then had used 14th113th century BC or poorly dated samples, rather than 15th cen- tury BC or earlier glass, a collaborative project was begun at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Corning Museum of Glass. The first goal was to build a corpus of early dated glasses, compositionally analyzed. As we proceeded, we therefore-decided to explore glassy materials contempo- rary with, or earlier than, our "pre-Malkata Palace" glasses as we called them (i.e., pre-1400 BC; figs. 1, 3-5,7-9). -

About Earthly, Water and Underwater Meetings of the Phoenicians and the Greeks

ISSN: 2148-9173 Vol: Issue:2 June 20 ,QWHUQDWLRQDO-RXUQDORI(QYLURQPHQWDQG*HRLQIRUPDWLFV ,-(*(2 LVDQLQWHUQDWLRQDO PXOWLGLVFLSOLQDU\SHHUUHYLHZHGRSHQDFFHVVMRXUQDO About Earthly, Water and Underwater Meetings of The Phoenicians and the Greeks. Mythological and Religious Ways of Transmission in The Eastern Mediterranean Krzysztof ULANOWSKI &KLHILQ(GLWRU 3URI'U&HP*D]LR÷OX &R(GLWRUV 3URI'U'XUVXQ=DIHUùHNHU3URI'UùLQDVL.D\D 3URI'U$\úHJO7DQÕNDQG$VVLVW3URI'U9RONDQ'HPLU (GLWRULDO&RPPLWWHH June $VVRF3URI'U$EGXOODK$NVX 75 $VVLW3URI'U8÷XU$OJDQFÕ 75 3URI'U%HGUL$OSDU 75 $VVRF3URI 'U$VOÕ$VODQ 86 3URI'U/HYHQW%DW 75 3URI'U3DXO%DWHV 8. øUúDG%D\ÕUKDQ 75 3URI'U%OHQW %D\UDP 75 3URI'U/XLV0%RWDQD (6 3URI'U1XUD\dD÷ODU 75 3URI'U6XNDQWD'DVK ,1 'U6RRILD7 (OLDV 8. 3URI'U$(YUHQ(UJLQDO 75 $VVRF3URI'U&QH\W(UHQR÷OX 75 'U'LHWHU)ULWVFK '( 3URI 'UdL÷GHP*|NVHO 75 3URI'U/HQD+DORXQRYD &= 3URI'U0DQLN.DOXEDUPH ,1 'U+DNDQ.D\D 75 $VVLVW3URI'U6HUNDQ.NUHU 75 $VVRF3URI'U0DJHG0DUJKDQ\ 0< 3URI'U0LFKDHO0HDGRZV =$ 3URI 'U 1HEL\H 0XVDR÷OX 75 3URI 'U 0DVDIXPL 1DNDJDZD -3 3URI 'U +DVDQ g]GHPLU 75 3URI 'U &KU\VV\3RWVLRX *5 3URI'U(URO6DUÕ 75 3URI'U0DULD3DUDGLVR ,7 3URI'U3HWURV3DWLDV *5 3URI'U (OLI6HUWHO 75 3URI'U1NHW6LYUL 75 3URI'U)VXQ%DOÕNùDQOÕ 75 3URI'U8÷XUùDQOÕ 75 'X\JXhONHU 75 3URI'U6H\IHWWLQ7Dú 75 $VVRF3URI'UgPHU6XDW7DúNÕQ 75 $VVLVW3URI'U7XEDhQVDO 75 'U 0DQRXVRV9DO\UDNLV 8. 'UøQHVH9DUQD /9 'U3HWUD9LVVHU 1/ 3URI'U6HOPDhQO 75 $VVRF3URI'U 2UDO<D÷FÕ 75 3URI'U0XUDW<DNDU 75 $VVRF3URI'Uø1R\DQ<ÕOPD] $8 $VVLW3URI'U6LEHO=HNL 75 $EVWUDFWLQJ DQG ,QGH[LQJ 75 ',=,1 '2$- ,QGH[ &RSHUQLFXV 2$-, 6FLHQWLILF ,QGH[LQJ 6HUYLFHV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO 6FLHQWLILF ,QGH[LQJ-RXUQDO)DFWRU*RRJOH6FKRODU8OULFK V3HULRGLFDOV'LUHFWRU\:RUOG&DW'5-,5HVHDUFK%LE62%,$' International Journal of Environment and Geoinformatics 8(2):210-217 (2021) Review Article About Earthly, Water and Underwater Meetings of The Phoenicians and the Greeks. -

Pre-Publication Proof

Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Preface xi List of Contributors xiii proof Introduction: Long-Distance Communication and the Cohesion of Early Empires 1 K a r e n R a d n e r 1 Egyptian State Correspondence of the New Kingdom: T e Letters of the Levantine Client Kings in the Amarna Correspondence and Contemporary Evidence 10 Jana Myná r ̌ová Pre-publication 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World 3 2 Mark Weeden 3 An Imperial Communication Network: T e State Correspondence of the Neo-Assyrian Empire 64 K a r e n R a d n e r 4 T e Lost State Correspondence of the Babylonian Empire as Ref ected in Contemporary Administrative Letters 94 Michael Jursa 5 State Communications in the Persian Empire 112 Amé lie Kuhrt Book 1.indb v 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM vi Contents 6 T e King’s Words: Hellenistic Royal Letters in Inscriptions 141 Alice Bencivenni 7 State Correspondence in the Roman Empire: Imperial Communication from Augustus to Justinian 172 Simon Corcoran Notes 211 Bibliography 257 Index 299 proof Pre-publication Book 1.indb vi 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM Chapter 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World M a r k W e e d e n T HIS chapter describes and discusses the evidence 1 for the internal correspondence of the Hittite state during its so-called imperial period (c. 1450– 1200 BC). Af er a brief sketch of the geographical and historical background, we will survey the available corpus and the generally well-documented archaeologi- cal contexts—a rarity among the corpora discussed in this volume. -

Paleoclimatic Reconstructions Based on the Study of Structures of Large

EGU21-6170 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-6170 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Paleoclimatic reconstructions based on the study of structures of large kurgans of the Bronze Age and soils buried under different structures for the steppe zone of Russia Alena Sverchkova and Olga Khokhlova Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems of Soil Science, Russian Academy of Sciences, Group of genesis and evolution of soils, Moscow, Russian Federation ([email protected]) Geoarchaeological studies of soils buried under burial mounds (kurgans) and materials of kurgan structures make it possible to solve a wide range of scientific problems. In the steppe zone of Russia, such studies are carried out in order to determine and compare the composition of buried soils and materials of kurgan structures, as well as to study the structure of earth monuments and to obtain data on the technology used by ancient people for their building. We carried out geoarchaeological studies in two key areas: in Krasnodar (kurgan Beisuzhek 9) and Stavropol (kurgan Essentuksky 1) regions. For each object, the particle-size distribution and physicochemical properties of the earthen materials of the kurgans and buried soils were investigated. Kurgan Essentuksky 1 was built in the second quarter of the 4th millennium BC (Maykop culture) according to a single plan in a short time (several decades). The kurgan with a height of 5.5-6.0 m and a diameter of 60 m consisted of four earthen and three stone structures. The earthen structures consisted of alternating layers of dark, slightly compacted humified and light dense carbonate-rich material that were taken from buried soils, i.e. -

Interactive Timeline of Bible History

Interactive Timeline Home China India Published in 2007 by Shawn Handran. Released in 2012 under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Uported License. Oceana-New World Greco-Roman Egypt Mesopotamia-Assyria Patriarchs Period Abraham to Joseph Interactive Timeline of Events in the Bible Exodus Period in Perspective of World History Judges Period Using Bible Chronologies Described in Halley’s Bible Handbook, The Ryrie Study Bible Kings Period and The Mystery of History with Comparative World Chronologies from Wikipedia Exile & Restoration Jesus the Messiah The Old Testament Or click here to begin Prehistory to 2100 bc China Period of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors ca. 2850 Start of Indus Valley civilization ca. 3000 India Published in 2007 by Shawn Handran. Released in 2012 under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Uported License. Caral civilization (Peru) ca. 2700 Oceana-New World Helladic (Greece) & Minoan civilization (Crete) ca. 2800 Greco-Roman Ancient Egyptian civilization ca. 3100 Egypt Old Kingdom Rise of Mesopotamian civilization ca. 3400 Akkadian Empire Mesopotamia-Assyria Tower of Babel (uncertain) The Age of the Patriarchs – Click Here to View Genealogy Abraham Adam Noah’s Flood born in Ur 4176 Click here to view how dates shown here were calculated 2520 2166 4000 bc Genesis 1-11 2500 bc 2100 bc The Old Testament Dates on this page are approximate and difficult to verify Xia Dynasty 2070 2100 to 1700 bc China Xia Dynasty Late Harappan 1700 India Published in 2007 by Shawn