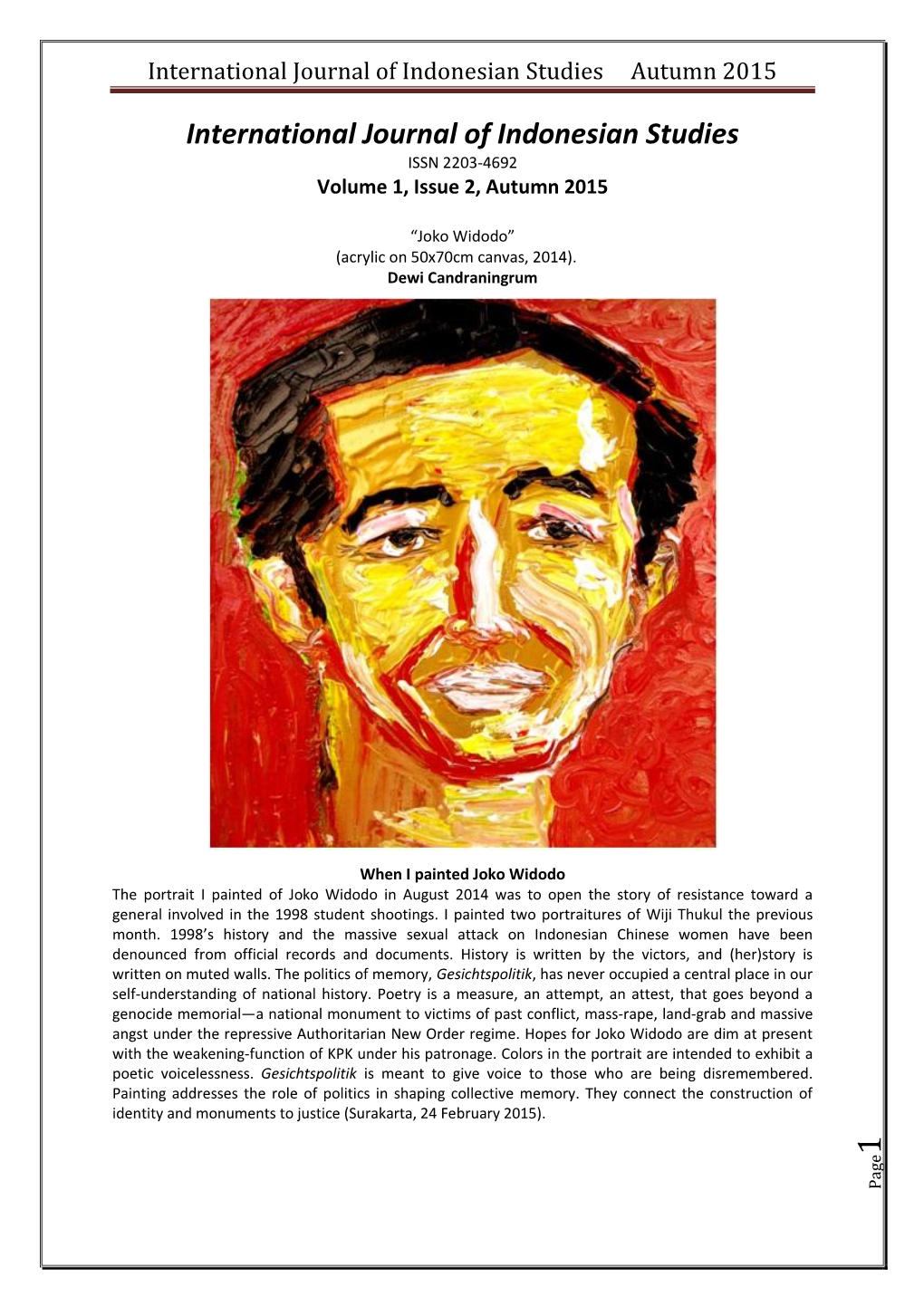

International Journal of Indonesian Studies Autumn 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythology and the Belief System of Sunda Wiwitan: a Theological Review in Cisolok of Sukabumi Regency of West Java, Indonesia

International Journal of Research and Review Vol.7; Issue: 4; April 2020 Website: www.ijrrjournal.com Research Paper E-ISSN: 2349-9788; P-ISSN: 2454-2237 Mythology and the Belief System of Sunda Wiwitan: A Theological Review in Cisolok of Sukabumi Regency of West Java, Indonesia Tita Rostitawati Department of Philosophy, State Islamic University of Sultan Amai Gorontalo, Indonesia ABSTRACT beliefs that are based on ideas in the teachings of ancestors or spirits. There are This study examined the mythology and belief several villages in West Java, which are systems adopted by the Sunda Wiwitan manifestations of the existence of community that were factually related to the indigenous peoples in Indonesia. credo system that was considered sacred in a The existence of traditional villages belief. Researcher in collecting data using interviews, observation, and literature review is a special attraction for the community methods. The process of data analysis was done because there is a unique culture and is with qualitative data analysis techniques. In the different from the others, such as the process of analyzing research data, the Sundanese people in the Cisolok village of researcher organized data, grouped data, and Sukabumi Regency. Human life requires a analyzed narratively. The results showed that belief in which the belief is in the form of the Sunda Wiwitan belief system worshiped religious teachings or views that, according ancestral spirits as an elevated entity. Aside to the community, are considered good and from worshiping ancestors, Sunda Wiwitan also true. In Cisolok of Sukabumi Regency, there had a God who was often called Sang Hyang are cultural and traditional elements that are Kersa. -

Reconceptualising Ethnic Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia

Reconceptualising Ethnic Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia Chang-Yau Hoon BA (Hons), BCom This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social and Cultural Studies Discipline of Asian Studies 2006 DECLARATION FOR THESES CONTAINING PUBLISHED WORK AND/OR WORK PREPARED FOR PUBLICATION This thesis contains sole-authored published work and/or work prepared for publication. The bibliographic details of the work and where it appears in the thesis is outlined below: Hoon, Chang-Yau. 2004, “Multiculturalism and Hybridity in Accommodating ‘Chineseness’ in Post-Soeharto Indonesia”, in Alchemies: Community exChanges, Glenn Pass and Denise Woods (eds), Black Swan Press, Perth, pp. 17-37. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter One of the thesis). ---. 2006, “Assimilation, Multiculturalism, Hybridity: The Dilemma of the Ethnic Chinese in Post-Suharto Indonesia”, Asian Ethnicity, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 149-166. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter One of the thesis). ---. 2006, “Defining (Multiple) Selves: Reflections on Fieldwork in Jakarta”, Life Writing, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 79-100. (A revised version of this paper appears in a few sections of Chapter Two of the thesis). ---. 2006, “‘A Hundred Flowers Bloom’: The Re-emergence of the Chinese Press in post-Suharto Indonesia”, in Media and the Chinese Diaspora: Community, Communications and Commerce, Wanning Sun (ed.), Routledge, London and New York, pp. 91-118. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter Six of the thesis). This thesis is the original work of the author except where otherwise acknowledged. -

Translating Modern Ideas Into Postcolonial Mosque Architecture in Indonesia

International Journal of Built Environment and Scientific Research Volume 02 Number 01 | June 2018 p-issn: 2581-1347 | e-issn: 2580-2607 | Pg. 39-46 Translating Modern Ideas into Postcolonial Mosque Architecture in Indonesia Mushab Abdu Asy Syahid1 1 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper tries to narrate the story of translation practices on the ideas and forms of modernity in the history of mosque architecture design development in Indonesia. The allow interactions to produce various approaches wider beyond religious context. The translation theory in postcolonialism field offers an alternate history on how postcolonial subjects define and take a significant role for their own culture in compromising the overcoming globalism and modernities. This attitude will question our historical narratives socio-political postcolonial subjects engage through such essential elements. In that way, a previous common image of mosque design thus ought to be reinvestigated, as well as a notion of “modern” in Indonesia history would be redeveloped while layering mosque architecture periodization. The mosque architecture types which were inspired from both Western—Eastern styles inevitably involved colonial-postcolonial contextuality in how dynamism of interchanges since Independence period interlinked to Dutch-Indies colonial times, Old and New Order regimes, to the Post-reform era interwoven present. Understanding this modernity translation transformation on each period following the spirit of the age may conclude that modern mosque architecture in Indonesia is not in a stagnant or linear but rather a complex flow periodization of its development. This also indicates the notion of “modern” has multiple intentions to culture and socio-political factors that always never solidify to any single universal definition. -

Pandangan Politik Soekarno Dalam Membangun Masjid Istiqlal

PANDANGAN POLITIK SOEKARNO DALAM MEMBANGUN MASJID ISTIQLAL SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Humaniora (S. Hum) Oleh: Achmad Rizki Nugraha NIM: 106022000894 PROGRAM STUDI SEJARAH PERADABAN ISLAM FAKULTAS ADAB DAN HUMANIORA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 1432 H./ 2011 M. PANDANGAN POLITIK SOEKARNO DALAM MEMBANGUN MASJID ISTIQLAL SKRIPSI Diajukan kepada Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora Untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Humaniora (S. Hum.) Oleh : Achmad Rizki Nugraha NIM : 106022000894 Pembimbing : Prof. Dr. H. Budi Sulistiono, M.Hum. NIP : 19541010 198803 1 001 PROGRAM STUDI SEJARAH PERADABAN ISLAM FAKULTAS ADAB DAN HUMANIORA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA TAHUN 2011 M/1432 H PENGESAHAN PANITIA UJIAN Skripsi berjudul PANDANGAN POLITIK SOEKARNO DALAM MEMBANGUN MASJID ISTIQLAL telah diujikan dalam sidang munaqasyah Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta pada 4 Januari 2011. skripsi ini telah diterima sebagai salah satu syarat memperoleh gelar Sarjana Humaniora (S.Hum) pada Program Studi Sejarah Peradaban Islam. Jakarta, 4 Januari 2011 SIDANG MUNAQASYAH Ketua Merangkap Anggota Sekertaris Merangkap Anggota Drs. H. M. Ma’ruf Misbah, MA. Sholikatus sa’diyah, M.Pd NIP: 19591222 199103 1 003 NIP: 19750417 200501 2 007 Anggota, Penguji Pembimbing Drs. Tarmizy Idris, MA. Prof. Dr. H. Budi Sulistiono, M.Hum. NIP : 19601212 199003 1 003 NIP : 19541010 198803 1 001 LEMBAR PERNYATAAN Dengan saya menyatakan bahwa: 1. Skripsi/tesis/disertasi merupakan hasil karya saya yang telah diajukan untuk memenuhi salah satu persyaratan memperoleh gelar strata1 /strata 2/ strata 3 di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 2. Semua sumber yang saya gunakan dalam penulisan ini telah saya cantumkan sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. -

Konflik Organisasi Nahdlatul Wathan Di Lombok Timur

KONFLIK ORGANISASI NAHDLATUL WATHAN DI LOMBOK TIMUR (Studi Pada Pengurus Dan Jama’ah Nahdlatul Wathan) SKRIPSI Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang Sebagai Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana (S-1) Sosiologi Oleh : ROSMALI HARUN 201210310311007 JURUSAN SOSIOLOGI FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS MUHAMMADIYAH MALANG 2016 LEMBAR PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini : Nama : Rosmali Harun Tempat, Tanggal Lahir : Kelayu Jorong, 30 Januuari 1993 NIN : 201210310311007 Jurusan : Sosiologi Fakultas : Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Menyatakan bahwa Karya Ilmiah/Skripsi saya yang berjudul Pandangan Masyarakat Lombok Timur Terhadap Dampak Dari Konflik Organisasi Nahdlatul Wathan (Studi Pada Pengurus dan Jama’ah Nahdlatul Wathan) bukan merupakan karya tulis orang lain, baik sebagian maupun keseluruhan kecuali dalam bentuk kutipan yang telah disebutkan sumbernya. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenar-benarnya. Apabila pernyataan ini tidak benar, saya bersedia mendapatkan sanksi akademis sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku. Malang, 30 Oktober 2016 Yang Menyatakan, Rosmali Harun vi LEMBAR PERSEMBAHAN Skripsi ini saya persembahkan untuk orang tua tercinta Ayahanda Muhammad Syukur dan Ibunda Hawariah untuk kedua adikku tersayang Susi Ratnasari dan Muhammad Fitra Vanani Mubarraq vii MOTTO HIDUP “setelah kesulitan akan datang kemudahan” viii KATA PENGANTAR Segala Puji dan syukur alhamdulillah kehadirat Allah SWT, atas segala kebesaran dan kemurahan-Nya yang telah melimpahkan segala rahmat serta hidayahnya sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan tugas skripsi yang berjudul “Pandangan Masyarakat Lombok Timur Terhadap Dampak Dari Konflik Organisasi Nahdlatul Wathan (Studi Pada Pengurus dan Jama’ah Nahdlatul Wathan)” sebagai salah satu persyaratan untuk menempuh gelar Sarjana (SI) Sosiologi. Skripsi ini merupakan program akademik di Jurusan Sosiologi Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang. -

Tri Tangtu on Sunda Wiwitan Doctrine in the XIV-XVII Century

TAWARIKH: Journal of Historical Studies, Volume 10(1), October 2018 Journal of Historical Studies ETTY SARINGENDYANTI, NINA HERLINA & MUMUH MUHSIN ZAKARIA Tri Tangtu on Sunda Wiwitan Doctrine in the XIV-XVII Century ABSTRACT: This article aims to reconstruct the concept of “Tri Tangtu” in the “Sunda Wiwitan” doctrine in the XIV-XVII century, when the Sunda kingdom in West Java, Indonesia was under the reign of Niskala Wastu (-kancana) at Surawisesa Palace in Kawali, Ciamis, until its collapse in 1579 AD (Anno Domini). “Tri Tangtu” absorbs the three to unite, one for three, essentially three things in fact one, the things and paradoxical attributes fused into and expanded outward. The outside looks calm, firm, one, but inside is continuously active in its entirety in various activities. This concept is still also continues on indigenous of Kanekes (Baduy) in Banten, Western Java. In achieving that goal, historical methods are used, consisting of heuristics, criticism, interpretation, and historiography. In the context of explanation used social sciences theory, namely socio-anthropology through the theory of religion proposed by Clifford Geertz (1973), namely religion as a cultural system that coherently explains the involvement between religion and culture. The results of this study show that the concept of “Tri Tangtu” consists of “Tri Tangtu dina Raga (Salira)”; “Tri Tangtu dina Nagara”; and “Tri Tangtu dina Buana”. About “Tri Tangtu dina Raga” is a system of human reciprocal relationship to the transcendent with “lampah, tekad, ucap (bayu-sabda- hedap)” or deed, strong will, and word. “Tri Tangtu dina Nagara” is a unity of “Rsi-Ratu-Rama” or Cleric, Ruler, and a Wise Oldmen. -

![IIAS Logo [Converted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2769/iias-logo-converted-562769.webp)

IIAS Logo [Converted]

Women from Traditional Islamic Educational Institutions in Indonesia Educational Institutions Indonesia in Educational Negotiating Public Spaces Women from Traditional Islamic from Traditional Islamic Women Eka Srimulyani › Eka SrimulyaniEka amsterdam university press Women from Traditional Islamic Educational Institutions in Indonesia Publications Series General Editor Paul van der Velde Publications Officer Martina van den Haak Editorial Board Prasenjit Duara (Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore) / Carol Gluck (Columbia University) / Christophe Jaffrelot (Centre d’Études et de Recherches Internationales-Sciences-po) / Victor T. King (University of Leeds) / Yuri Sadoi (Meijo University) / A.B. Shamsul (Institute of Occidental Studies / Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) / Henk Schulte Nordholt (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) / Wim Boot (Leiden University) The IIAS Publications Series consists of Monographs and Edited Volumes. The Series publishes results of research projects conducted at the International Institute for Asian Studies. Furthermore, the aim of the Series is to promote interdisciplinary studies on Asia and comparative research on Asia and Europe. The International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) is a postdoctoral research centre based in Leiden and Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Its objective is to encourage the interdisciplinary and comparative study of Asia and to promote national and international cooperation. The institute focuses on the humanities and social -

Tuan Guru and Ahmadiyah in the Redrawing of Post-1998 Sasak-Muslim Boundary Lines in Lombok

CONTESTED IDENTITIES: TUAN GURU AND AHMADIYAH IN THE REDRAWING OF POST-1998 SASAK-MUSLIM BOUNDARY LINES IN LOMBOK BY SITTI SANI NURHAYATI A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2020 i Abstract This study examines what drives the increasing hostility towards Ahmadiyah in post- Suharto Lombok. Fieldwork was undertaken in three villages – Pemongkong, Pancor and Ketapang – where Ahmadiyah communities lived and experienced violent attacks from 1998 to 2010. The stories from these villages are analysed within the context of a revival of local religious authority and the redefinition of the paradigm of ethno-religious identity. Furthermore, this thesis contends that the redrawing of identity in Lombok generates a new interdependency of different religious authorities, as well as novel political possibilities following the regime change. Finally, the thesis concludes there is a need to understand intercommunal religious violence by reference to specific local realities. Concomitantly, there is a need for greater caution in offering sweeping universal Indonesia-wide explanations that need to be qualified in terms of local contexts. ii iii Acknowledgements Alhamdulillah. I would especially like to express my sincere gratitude and heartfelt appreciation to my primary supervisor, Professor Paul Morris. As my supervisor and mentor, Paul has taught me more than I could ever give him credit for here. My immense gratitude also goes to my secondary supervisors, Drs Geoff Troughton and Eva Nisa, for their thoughtful guidance and endless support, which enabled me, from the initial to the final stages of my doctoral study, to meaningfully engage in the whole thesis writing process. -

Ulumuna Journal of Islamic Studies Publish by State Islamic Institute Mataram Vol

Ulumuna Journal of Islamic Studies publish by State Islamic Institute Mataram Vol. 19, No. 2, 2015, p. 251-278 Print ISSN: 1411-3457, Online ISSN: 2355-7648 Available online at http://ejurnal.iainmataram.ac.id/index.php/ulumuna SOCIAL RESILIENCE OF MINORITY GROUP: STUDY ON SHIA REFUGEES IN SIDOARJO AND AHMADIYYA REFUGEES IN MATARAM1 Cahyo Pamungkas Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia Email:[email protected] Abstract:This research conceptually aims to find out the strategy the Shia community in Sidoarjo, East Java, and Ahmadiyya community in Mataram, West Nusa Tenggara, have employed to defend themselves from the pressure of the state and Sunni Muslim as majority group due to the differences in textual interpretation toward Islamic Holy Scriptures (The Qur‟an). The theoretical implication from this study is to evaluate and criticize social resilience concept which refers to developmentalistic perspectives such as the use of social capital. In this article, social resilience is closely related to strategy of minorities to establish a tolerant multi religious community. This study argues that social resilience of religious minority groups, i.e. Shia in Sidoarjo and Ahmadiyya in Mataram, is formed by various aspects, such as the government policies on religious life, history of group formation, social relations and network, understanding towards religious values and spirituality, and cultural bonds in the community. Key words: religion, social resilience, refugees, religious minority, and community strategy. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20414/ujis.v19i2.418 1This article is a revised version of the author‟s LIPI research monograph (2015) entitled “Social Resilience of Religious Minority Group: A Study on Shia refugees in Sidoarjo and Ahmadiyya refugees in Mataram. -

Bugis Settlers in East Kalimantan's Kutai National Park

Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 1 BUGIS SETTLERS IN EAST KALIMANTANÕS KUTAI NATIONAL PARK THEIR PAST AND PRESENT AND SOME POSSIBILITIES FOR THEIR FUTURE Andrew P. Vayda and Ahmad Sahur CIFOR CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FORESTRY RESEARCH CIFOR Special Publication Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 2 © 1996 Center for International Forestry Research Published by Center for International Forestry Research mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia tel.: +62-251-622622 fax: +62-251-622100 e-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://www.cgiar.org/cifor with support from UNDP/UNESCO/Government of Indonesia Project INS/93/004 on Management Support to Kutai National Park Jl. M.H. Thamrin 14 Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia ISBN 979-8764-12-9 Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 3 CONTENTS Preface v Introduction 1 Some Teluk Pandan Findings Amenability to Relocation 7 The Pull of Industry and the Pull of the Forest 8 Compensation for Land 11 Patrons and Clients 15 Willingness to Move in Return only for Compensation 18 Effects of Compensation Expectations on Buying and Using Land 24 Comparisons Selimpus 27 Sangkimah 33 Bugis Settlers Relocated to Km 24 40 Bugis Settlers Relocated from Bukit Soeharto 43 Concluding Remarks 49 References Cited 52 Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 5 PREFACE This report presents detailed results of human ecology-anthropological research in a very specific place, with a specific ethnic group, and deals with a context which a particular national government sees as a specific ÒproblemÓ. This would seem to make it an unlikely candi- date for publication by CIFOR, an institution mandated and dedicated to research which is of widespread public benefit. -

Pemikiran Abdurrahman Wahid Tentang Islam Dan Pluralitas

PEMIKIRAN ABDURRAHMAN WAHID TENTANG ISLAM DAN PLURALITAS Zainal Abidin Jurusan Psikologi, Faculty of Humanities, BINUS University Jln. Kemanggisan Ilir III No. 45, Kemanggisan - Palmerah, Jakarta Barat 11480 ABSTRACT This article clarifies a research that concerned with Wahid’s thoughts and actions that saw Islam from its basic value, not merely as a symbol. Therefore, Wahid presented Islam from democratic and cultural sides. To present the phylosophical analysis of Wahid’s thoughts, the research applies hermeneutics approach and library research, especially reading Wahid’s books as the primary sources, and others’ books related to Wahid’s thoughts as the secondary sources. It can be concluded that Islam presented by Wahid is the Islam that relates to softness, adoring loves, defending the weakness and minority, sustaining to lead the justice, having faith and honesty, tolerance, inclusive, and showing plualities. Keywords: Islam, Islam basic value, plurality ABSTRAK Artikel ini menjelaskan penelitian tentang pemikiran dan tindakan Wahid yang lebih menekankan keislaman pada nilai dasar Islam, bukan pada simbol belaka. Karena itu, Wahid menampilkan Islam pada wajah demokrasi dan kebudayaan. Sebagai suatu analisis filosofis terhadap pemikiran Wahid, secara metodologis, penelitian ini menggunakan pendekatan hermeneutik (hermeneutics approach) dan dalam pencarian data menggunakan penelitian kepustakaan (library research) dengan cara membaca buku karya Wahid sebagai data primer, dan buku karya pengarang lain yang berhubungan dengan telaah ini sebagai data sekunder. Disimpulkan bahwa Islam yang ditampilkan oleh Wahid adalah Islam yang penuh dengan kelembutan, Islam yang diliputi oleh cinta-kasih, Islam yang membela kaum yang lemah dan minoritas, Islam yang senantiasa menegakan keadilan, Islam yang setia pada kejujuran, dan Islam yang toleran, inklusif dan pluralis. -

28 Tohari's Women the Depiction of Banyumas

Proceedings TOHARI'S WOMEN THE DEPICTION OF BANYUMAS WOMEN IN AHMAD TOHARI'S LITERARY WORKS Dhenok Praptiningrum Institut Teknologi Telkom Purwokerto, Purwokerto [email protected] Abstract: As part of Javanese culture, Banyumas actually has its particular Javanese social and cultural characteristics. The social structure and culture, especially related to the position and the definition of women, are reflected in Ahmad Tohari's literary works. In some of his literary works such as Ronggeng Dukuh Paruk (The Dancer) and Bekisar Merah (The Red Bekisar) Tohari even portraits Banyumas women as the main characters of the novel. Both in Ronggeng Dukuh Paruk and Bekisar Merah, the women characthers depicted in figure of strong and powerful women. Meanwhile, Lingkar Tanah Air and Kubah portrait women characters almost in the opposite figure of piety and submissive women. Thus, this paper would analyze the depiction of Banyumas women in Tohari's four novels to provide specific descriptions of Banyumas women archetype from the perspectives of religious life, the role in a family, and the role as a woman in a society. Keywords: Banyumas women, Ahmad Tohari, women depiction, women archetype, Indonesian literature INTRODUCTION There have been various kind of studies about Javanese culture and Indonesian literary works. However, the studies mainly focus on the idea of Javanese in general that build the idea of Javanese culture, especially women archetype, as particular one kind of Javanese idea. As part of Javanese culture, Banyumas is geographically located in Central Java, in fact has its own specific Javanese culture, value, even accents. Thus, this study focuses on the idea of Banyumas culture reflected in three novels written by Ahmad Tohari, Ronggeng Dukuh Paruk – The Dancer (1982), Bekisar Merah – The Red Bekisar (1993), and Kubah – The Dome (1980).