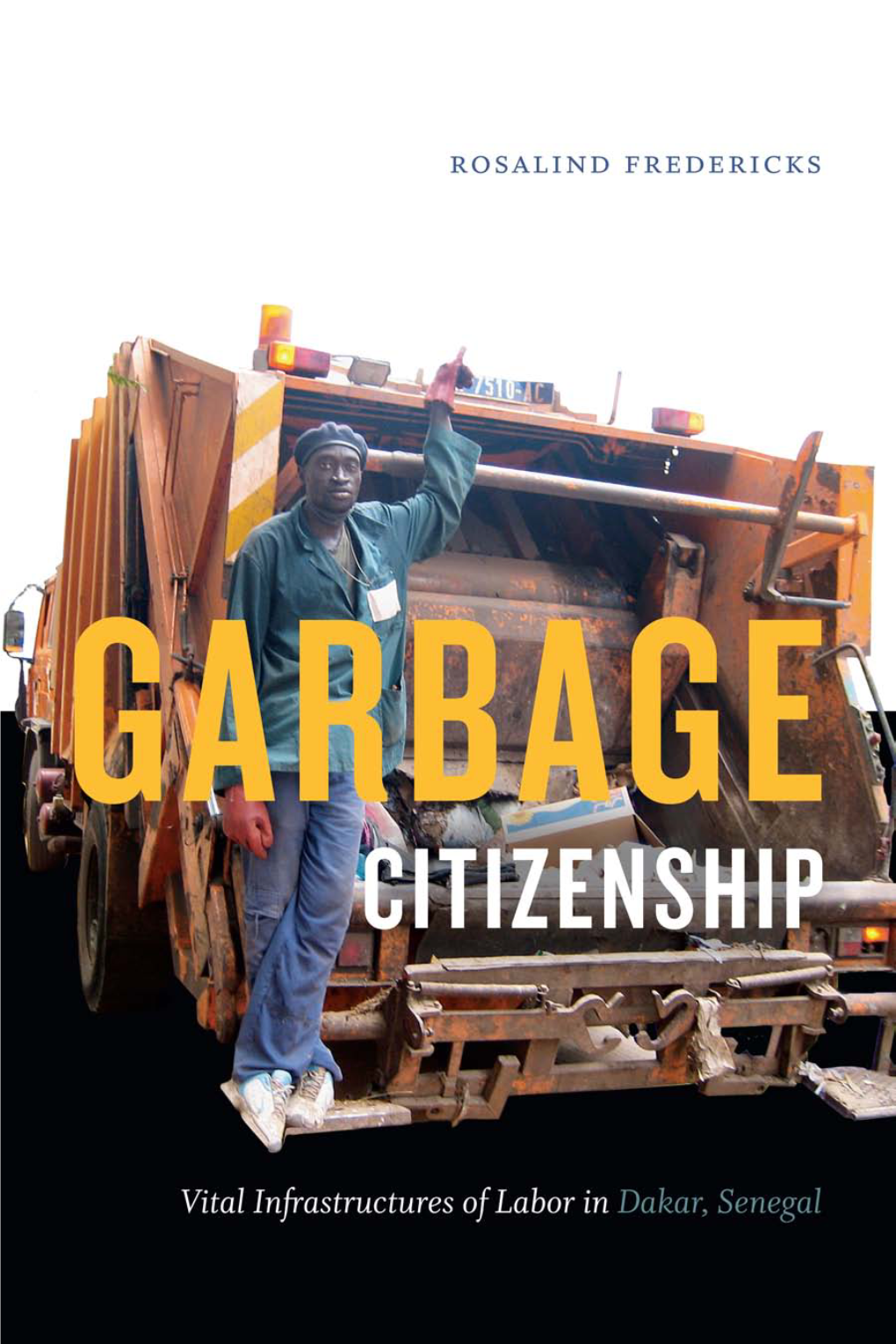

Garbage Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

BANK of AFRICA SENEGAL Prie Les Personnes Dont Les Noms Figurent

COMMUNIQUE COMPTES INACTIFS BANK OF AFRICA SENEGAL prie les personnes dont les noms figurent sur la liste ci- dessous de bien vouloir se présenter à son siège (sis aux Almadies, Immeuble Elan, Rte de Ngor) ou dans l’une de ses agences pour affaire les concernant AGENCE DE NOM NATIONALITE CLIENT DOMICILIATION KOUASSI KOUAME CELESTIN COTE D'IVOIRE ZI PARTICULIER 250383 MME SECK NDEYE MARAME SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100748 TOLOME CARLOS ADONIS BENIN INDEPENDANCE 102568 BA MAMADOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101705 SEREME PACO BURKINA FASO INDEPENDANCE 250535 FALL IBRA MBACKE SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100117 NDIAYE IBRAHIMA DIAGO SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 251041 KEITA FANTA GOGO SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101860 SADIO MAMADOU SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 250314 MANE MARIAMA SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 103715 BOLHO OUSMANE ROGER NIGER INDEPENDANCE 103628 TALL IBRAHIMA SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100812 NOUCHET FANNY J CATHERINE SENEGAL MERMOZ 104154 DIOP MAMADOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100893 NUNEZ EVELYNE SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101193 KODJO AHIA V ELEONORE COTE D'IVOIRE PARCELLES ASSAINIES 270003 FOUNE EL HADJI MALICK SENEGAL MERMOZ 105345 AMON ASSOUAN GNIMA EMMA J SENEGAL HLM 104728 KOUAKOU ABISSA CHRISTIAN SENEGAL PARCELLES ASSAINIES 270932 GBEDO MATHIEU BENIN INDEPENDANCE 200067 SAMBA ALASSANE SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 251359 DIOUF LOUIS CHEIKH SENEGAL TAMBACOUNDA 960262 BASSE PAPE SEYDOU SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 253433 OSENI SHERIFDEEN AKINDELE SENEGAL THIES 941039 SAKERA BOUBACAR FRANCE DIASPORA 230789 NDIAYE AISSATOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 111336 NDIAYE AIDA EP MBAYE SENEGAL LAMINE GUEYE -

Liste Des Sous Agents Rapid Transfer

LISTE DES SOUS AGENTS RAPID TRANSFER DAKAR N° SOUS AGENTS VILLE ADRESSE 1 ETS GORA DIOP DAKAR 104 AV LAMINE GUEYE DAKAR 2 CPS CITÉ BCEAO DAKAR 111 RTE DE L'AÉROPORT CITE BCEAO2 COTE BOA 113 AVENUE BLAISE DIAGNE NON LOIN DE LA DIBITERIE ALLA SECK DU COTÉ 3 BBAS DAKAR OPPOSÉ 123 RUE MOUSSE DIOP (EX BLANCHOT) X FELIX FAURE PRES MOSQUEE 4 FOF BOUTIK DAKAR RAWANE MBAYE DAKAR PLATEAU 5 PAMECAS FASS PAILLOTTES DAKAR 2 VOIES FASS PARALLELE SN HLM, 200 M AVANT LE CASINO MEDINA 6 MAREGA VOYAGES DAKAR 32, RUE DE REIMS X MALICK SY 7 CPS OUEST FOIRE DAKAR 4 OUEST FOIRE RTE AÉROPORT FACE PHILIP MAGUILENE 8 CPS PIKINE SYNDICAT DAKAR 4449 TALY BOUBESS MARCHÉ SYNDICAT A COTE DU STADE ALASSANE DJIGO 9 TIMERA CHEIKHNA DAKAR 473 ARAFAT GRAND YOFF EN FACE COMMISSARIAT GRAND YOFF 5436 LIBERTÈ 5 NON LOIN DU ROND POINT JVC AVANT LA PHARMACIE MADIBA EN PARTANT DU ROND POINT JVC DIRECTION TOTAL LIBERTÉ 6 SUR 10 ERIC TCHALEU DAKAR LES 2 VOIES 5507 LIBERTÉ 5 EN FACE DERKLÉ ENTRE L'ECOLE KALIMA ET LA BOUTIQUE 11 SY JEAN CLEMENT DAKAR COSMETIKA 12 ETS SOW MOUHAMADOU SIRADJ DAKAR 7 RUE DE THIONG EN FACE DE L'ECOLE ADJA MAMA YACINE DIAGNE 13 TOPSA TRADE DAKAR 71 SOTRAC ANCIENNE PISTE EN FACE URGENCE CARDIO MERMOZ 14 DAFFA VOYAGE DAKAR 73 X 68 GUEULE TAPEE EN FACE DU LYCEE DELAFOSSE 15 ETS IDRISSA DIAGNE DAKAR 7765 BIS MERMOZ SICAP 16 MABOULA SERVICE DAKAR 7765 SICAP MERMOZ EN FACE AMBASSADE GABON 17 EST MAMADOU MAODO SOW DAKAR ALMADIE LOT°12 VILLA 084 DAKAR 18 DIEYE AISSATOU DAKAR ALMADIES 19 PAMECAS GRAND YOFF 1 DAKAR ARAFAT GRAND YOFF AVANT LA POLICE 2 20 CPS GUEDIAWAYE -

Market-Oriented Urban Agricultural Production in Dakar

CITY CASE STUDY DAKAR MARKET-ORIENTED URBAN AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN DAKAR Alain Mbaye and Paule Moustier 1. Introduction Occupying the Sahelian area of the tropical zone in a wide coastal strip (500 km along the Atlantic Ocean), Senegal covers some 196,192 km2 of gently undulating land. The climate is subtropical, with two seasons: the dry season lasting 9 months, from September to July, and the wet season from July to September. The Senegalese GNP (Gross National Product) of $570 per capita is above average for sub-Saharan Africa ($490). However, the economy is fragile and natural resources are limited. Services represent 60% of the GNP, and the rest is divided among agriculture and industry (World Bank 1996). In 1995, the total population of Senegal rose above 8,300,000 inhabitants. The urbanisation rate stands at 40%. Dakar represents half of the urban population of the region, and more than 20% of the total population. The other main cities are much smaller (Thiès: pop. 231,000; Kaolack: pop. 200000; St. Louis: pop. 160,000). Table 1: Basic facts about Senegal and Dakar Senegal Dakar (Urban Community) Area 196,192 km2 550 km2 Population (1995) 8,300,000 1,940,000 Growth rate 2,9% 4% Source: DPS 1995. The choice of Dakar as Senegal’s capital was due to its strategic location for marine shipping and its vicinity to a fertile agricultural region, the Niayes, so called for its stretches of fertile soil (Niayes), between parallel sand dunes. Since colonial times, the development of infrastructure and economic activity has been concentrated in Dakar and its surroundings. -

Dakar's Municipal Bond Issue: a Tale of Two Cities

Briefing Note 1603 May 2016 | Edward Paice Dakar’s municipal bond issue: A tale of two cities THE 19 MUNICIPALITIES OF THE CITY OF DAKAR Central and municipal governments are being overwhelmed by the rapid growth Cambérène Parcelles Assainies of Africa’s cities. Strategic planning has been insufficient and the provision of basic services to residents is worsening. Since the 1990s, widespread devolution has substantially shifted responsibility for coping with urbanisation to local Ngor Yoff Patte d’Oie authorities, yet municipal governments across Africa receive a paltry share of Grand-Yoff national income with which to discharge their responsibilities.1 Responsible and SICAP Dieuppeul-Derklé proactive city authorities are examining how to improve revenue generation and Liberté Ouakam HLM diversify their sources of finance. Municipal bonds may be a financing option for Mermoz Biscuiterie Sacré-Cœur Grand-Dakar some capital cities, depending on the legal and regulatory environment, investor appetite, and the creditworthiness of the borrower and proposed investment Fann-Point Hann-Bel-Air E-Amitié projects. This Briefing Note describes an attempt by the city of Dakar, the capital of Senegal, to launch the first municipal bond in the West African Economic and Gueule Tapée Fass-Colobane Monetary Union (WAEMU) area, and considers the ramifications of the central Médina Dakar-Plateau government blocking the initiative. Contested capital Sall also pressed for the adoption of an African Charter on Local Government and the establishment of an During the 2000s President Abdoulaye Wade sought African Union High Council on Local Authorities. For Sall, to establish Dakar as a major investment destination those closest to the people – local government – must and transform it into a “world-class” city. -

Senegal: Transport & Urban Mobility Project (P101415)

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results Report SENEGAL: TRANSPORT & URBAN MOBILITY PROJECT (P101415) SENEGAL: TRANSPORT & URBAN MOBILITY PROJECT (P101415) AFRICA | Senegal | Transport Global Practice | IBRD/IDA | Investment Project Financing | FY 2010 | Seq No: 17 | ARCHIVED on 23-Dec-2019 | ISR39922 | Public Disclosure Authorized Implementing Agencies: Agence des Travaux et de Gestion des Routes (AGEROUTE Senegal), Agence des Travaux et de Gestion des Routes (AGEROUTE Sénégal), Conseil Exécutif des Transports Urbains de Dakar (CETUD), Coordination du PATMUR, Ministere de l'Economie, des Finances et du PLan, Agence Autonome de Gestion des Routes (AGEROUTE ), Conseil Exécutif des Transports Urbains de Dakar (CETUD) Key Dates Key Project Dates Bank Approval Date: 01-Jun-2010 Effectiveness Date: 29-Dec-2010 Planned Mid Term Review Date: 01-Oct-2013 Actual Mid-Term Review Date: 31-Oct-2013 Original Closing Date: 30-Sep-2014 Revised Closing Date: 31-Dec-2019 Public Disclosure Authorized pdoTable Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The development objectives of this project are: (i) to improve effective road management and maintenance, both at national level and in urban areas; and (ii) to improve public urban transport in the Greater Dakar Area (GDA). Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project Objective? Yes Board Approved Revised Project Development Objective (If project is formally restructured) - Public Disclosure Authorized Components -

The Challenges of Urban Growth in West Africa: the Case of Dakar, Senegal

University of Mumbai The Challenges of Urban Growth in West Africa: The Case of Dakar, Senegal Working Paper: No. 8 Dolores Koenig Center for African Studies Area Studies Building Behind Marathi Bhasha Bhavan University of Mumbai Vidyanagari, Santacruz (E) Mumbai: 400 098. Tel Off: 022 2652 00 00 Ext. 417. E mail: [email protected] [email protected] February 2009 1 Contents Resume Introduction 3 Dakar: The Challenges of Urban Growth 5 Key Problems Facing Dakar 7 Dakar’s Environmental Challenges 8 Furnishing Housing and Essential Services 11 Planning Procedures 19 Socio-cultural Issues 24 Conclusion: Outstanding Questions 29 Bibliography 31 Figure 1: Map of Senegal 32 Figure 2: Proposed Route of the Dakar to Diamnadio Toll road 33 End Notes 33 2 Introduction Sub-Saharan Africa is becoming increasingly urbanized. If Southern African is the most urbanized region on the continent, West Africa ranks second. In 2000, 53.9% of southern Africa’s population was urban, while 39.3% of West Africans lived in urban areas. By 2030, it is estimated that Africa as a whole will be an “urban” continent, having reached the threshold of 50% urban residents. Estimates are that southern Africa will then be 68.6% urban and West Africa 57.4% urban. In contrast, East Africa will be less than 33.7% urban (UN Habitat 2007:337). Although most African cities remain small by world standards, their rates of growth are expected to be greater than areas that already include large cities. For example, the urban population of Senegal, the focus of this paper is expected grow by 2.89%/year from 2000-2010 and by 2.93% from 2010 to 2020. -

Facts and Figures

Facts and figures Land area: 197,000 sq km Population (1993 estimate): 8 million Annual population growth (1990-2000 estimate): 2.8% Life expectancy at birth: 48 years Main urban centres: Dakar region (pop. 2 million), Thies (319,000), Kaolack (181,000), St Louis (179,000) Principal ethnic groups: Wolof, Serer, Peulh, Toucouleur, Diola Languages: Wolof, Pulaar, and other national languages. Official language (understood by approximately 20%): French Adult literacy: 38% GDP per capita (1992): £440 (equivalent to approximately £250 at 1994 exchange rates) Annual growth of GNP (average for 1980- 90): 0% Nutrition: Daily calorie supply per person, as percentage of requirements: 84% Health: Percentage of population with access to safe water: urban 79%, rural 38% Currency: 1 Franc CFA = 1 centime (under m mi* a fixed exchange rate, 100 FCFA = 1 • - _r /' • .:,:._-•: ^. ; French franc) .r- •. ''>.:• r. •; Main agricultural production: peanuts, millet, sorghum, manioc, rice, cotton, livestock Principal exports: fish and fish products, peanut products, phosphates, chemicals Foreign debt (1992): US$3.6 billion Baobab tree 60 Dates and events llth century AD: Arrival of Islam with 1876: Resistance leader Lat-Dyor is killed. the conquering Almoravids from North The coastal region is annexed by the Africa. French. Dakar-St Louis railway con- 12th century: Founding of the Kingdom of structed. Djoloff. 1871-80: Policy of 'assimilation' grants 15th century: Arrival of the first French citizenship to inhabitants of St Portuguese explorers. Louis, Dakar, Goree, and Rufisque, 1588-1677: The Dutch establish fortified with the right to elect Deputies to the trading posts along the Senegal coast. French National Assembly. -

Discussion Papers on Ncds and Development Cooperation Agendas

WHO Open call for interest: Discussion papers on NCDs and development cooperation agendas Introduction: • According to Dr Ala Alwan – Assistant Director General of WHO, noncommunicable diseases will have their greatest increase in the African Region (27%) in the next ten years. • Noncommunicable diseases have an impact on all societies. They undermine social and economic development throughout the world. In Senegal, a lower middle-income country, they currently represent 34% of total deaths. • A WHO comparative study country by country 1 shows that around 30% of the Senegalese population is suffering from cardio-vascular diseases. The main risk factors are bad nutrition, a lack of physical exercise, and the use of tobacco and alcohol. • According to Professor Abdoul Kane, Head of the Cardiology Department at the Grand Yoff Teaching Hospital in Senegal, a survey conducted in 2010 on one sample representative of the population of Saint-Louis shows prevalence of the risk factors which get closer to that of the developed countries which register 46 % of arterial high blood pressure, 10.5 % of diabetes, 18.4 % of smoking among the men and 23 % of obesity. According to the published results of the survey the representative sample of Senegal shows a prevalence of 46% of arterial high blood pressure, 10,4 % of diabetes, 5,8% of smokers, 23% of obesity and 44% of physical inactivity.2 • According to the National Health Development Plan of Senegal 2009-2018, one of the sectorial objectives is the prevention and the fight against illnesses. The eleven strategies under this objective include health promotion. Regarding noncommunicable diseases the report mentions: ”Today, Senegal faces the double load of morbidity due to communicable and the non communicable diseases. -

Senegal Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Senegal Country Report Status Index 1-10 6.00 # 51 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 7.12 # 36 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.89 # 82 of 129 Management Index 1-10 6.25 # 24 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Senegal Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Senegal 2 Key Indicators Population M 13.7 HDI 0.470 GDP p.c. $ 1944.0 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.9 HDI rank of 187 154 Gini Index 40.3 Life expectancy years 63.0 UN Education Index 0.402 Poverty3 % 55.2 Urban population % 42.9 Gender inequality2 0.540 Aid per capita $ 52.5 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The most important element of democratic and economic transformation from 2011 to 2013 has been the peaceful change of government in March/April 2012 after Macky Sall won the presidential elections. Between 2009 and President Sall’s election, Senegal underwent a period of political disputes that distracted attention away from the real problems of the country, stalling development. -

Et S O C I a L E 2 0

République du Sénégal Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES -------------o------------- DIRECTION DE LA PREVISION ET DE LA STATISTIQUE -------------o------------- SERVICE REGIONAL DE LA PREVISION ET DE LA STATISTIQUE – DAKAR S I T U A T I O N E C O N O M I Q U E et S O C I A L E 2 0 0 4 SRPS/Dakar © Octobre 2005 SERVICE REGIONAL DE LA PREVISION ET DE LA STATISTIQUE DE DAKAR Chef de Service Ama Ndaw KAMBE Adjoint Mamadou NGOM Secrétaire Madame Awa CISSOKHO SOUMARE Chauffeur Pape Macoumba THIOUNE AGENTS D’APPUI Agent de saisie : Madame Fatou DIARISSO DIOUF Vaguemestre : Madi CAMARA Gardien : Ibrahima DIARRA SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE DE LA REGION DE DAKAR – 2004 Service Régional de la Prévision et de la Statistique de Dakar. Liberté VI – villa 7944 – Terminus P9 – Téléphone 646 95 20 PRESENTATION La région de Dakar est située dans la presqu’île du Cap Vert et s’étend sur une superficie de 550 km², soit 0,28% du territoire national. Elle est comprise entre les 17° 10 et 17° 32 longitude Ouest et les 14°53 et 14°35 latitude Nord. Elle est limitée à l’Est par la région de Thiès et par l’Océan Atlantique dans ses parties Nord, Ouest et Sud. Dakar, ancienne capitale de l’AOF, avait connu un rayonnement politique et économique international resplendissant. Sur le plan administratif, la région est subdivisée en 4 départements : - Dakar, - Pikine, - Guédiawaye, - Rufisque). Quatre (4) villes : - Dakar, - Pikine, - Guédiawaye, - Rufisque. Trois (3) communes : - Bargny, - Diamniadio, - Sébikotane. -

Carte Administrative De La Région De Dakar

Carte administrative de la région de Dakar Extrait du Au Senegal http://www.au-senegal.com Dakar Carte administrative de la région de Dakar - Français - Découvrir le Sénégal, pays de la teranga - Sénégal administratif - Date de mise en ligne : vendredi 24 aot 2007 Description : Le Sénégal géographique • Gorée Un quart dheure seulement en chaloupe suffit pour relier Gorée au reste du continent. (...) • Toubab Diallao Entre plages de sable fin, falaises dargile et collines de pierres, Toubab Dialaw est (...) • Dakar Copyright © Au Senegal Page 1/5 Carte administrative de la région de Dakar Ancien village de pêcheurs Lebou et Wolof, Dacar ou Dahar qui signifie « tamarinier » (...) • Cap-vert La presquîle du Cap-Vert, qui abrite Dakar, la capitale du pays, constitue le point le (...) • Petite Côte La Petite Côte sétend sur près de 70 km au sud-est de Dakar, entre Rufisque et Joal (...) • Région centre Le Centre-Ouest du Sénégal, doté dune très forte population, présente un paysage sahélien (...) • Sine Saloum Dune grande richesse historique et culturelle, la région naturelle du Sine Saloum, au (...) • Casamance La région naturelle de la Casamance a des limites qui tiennent à la fois de la nature (...) • Saint-Louis et le delta du fleuve La zone du delta du fleuve comprend plusieurs sites naturels remarquables. Grâce à la (...) • Vallée du fleuve Le fleuve Sénégal sécoule paisiblement en marquant la frontière avec le Mali à lEst et (...) • Sénégal Oriental La région orientale du Sénégal est certainement la plus riche en surprises et en (...)