Trends in First Amendment Protection of Commercial Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

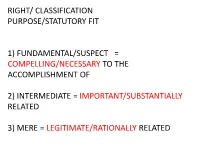

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: the Gentile V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 43 1993 The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision Suzanne F. Day Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Suzanne F. Day, The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision, 43 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1347 (1993) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol43/iss4/43 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE SUPREME COURT'S AITACK ON ATTORNEYS' FREEDOM OF ExPRESSION: THE GENTILE v. STATE BAR OF NEVADA DECISION TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............. ............ 1349 A. The Dilemma of the Defense Attorney ....... 1349 B. State Court Rules Restricting Attorney Communication with the Media ............. 1350 11. CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS RAISED BY RESTRICTING PRETRIAL PUBLICITY THROUGH CURBING THE SCOPE OF ATrORNEY SPEECH: THE FAIR TRIAL - FREE PRESS DEBATE ...... ........................ 1351 A. The Sheppard v. Maxwell Decision: The United States Supreme Court's Directive to Trial Court Judges ............................ 1352 B. The Conflicting First Amendment Rights of Attorneys, Sixth Amendment Rights of the Defendant, and the State and Public Interest in the Impartial Administration of Justice ........... 1355 1. What the Amendments Guarantee ......... 1355 2. -

Attorney Solicitation: the Scope of State Regulation After <Em>Primus</Em> and <Em>Ohralik</Em>

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 12 1978 Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik David A. Rabin University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Profession Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Rabin, Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik, 12 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 144 (1978). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol12/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTORNEY SOLICITATION: THE SCOPE OF STATE REGULATION AFTER PRIMUS AND OHRALIK Within the past few years, there has been a growing concern both within and without the legal profession-over increasing the layman's access to legal services. Two of the principal means of increasing this access, advertising and solicitation, 1 have long been prohibited by the organized bar, although a few minor exceptions have been allowed. In lff77, the question of the constitutionality of prohibitions against legal advertising was presented to the United States Supreme Court in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona. 2 The Court ruled in a landmark decision that certain types of advertising could not be prohibited, but expressly reserved the question of the con stitutionality of prohibitions against in-person solicitation.3 Eleven months after Bates, the Court decided two attorney solicitation cases, In re Primus4 and Ohra/ik v. -

Exceptions to the First Amendment

Order Code 95-815 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Updated July 29, 2004 Henry Cohen Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Summary The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press....” This language restricts government both more and less than it would if it were applied literally. It restricts government more in that it applies not only to Congress, but to all branches of the federal government, and to all branches of state and local government. It restricts government less in that it provides no protection to some types of speech and only limited protection to others. This report provides an overview of the major exceptions to the First Amendment — of the ways that the Supreme Court has interpreted the guarantee of freedom of speech and press to provide no protection or only limited protection for some types of speech. For example, the Court has decided that the First Amendment provides no protection to obscenity, child pornography, or speech that constitutes “advocacy of the use of force or of law violation ... where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Court has also decided that the First Amendment provides less than full protection to commercial speech, defamation (libel and slander), speech that may be harmful to children, speech broadcast on radio and television, and public employees’ speech. -

Admission to the Bar: a Constitutional Analysis

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Issue 3 - April 1981 Article 4 4-1981 Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis Ben C. Adams Edward H. Benton David A. Beyer Harrison L. Marshall, Jr. Carter R. Todd See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Ben C. Adams; Edward H. Benton; David A. Beyer; Harrison L. Marshall, Jr.; Carter R. Todd; and Jane G. Allen Special Projects Editor, Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis, 34 Vanderbilt Law Review 655 (1981) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol34/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis Authors Ben C. Adams; Edward H. Benton; David A. Beyer; Harrison L. Marshall, Jr.; Carter R. Todd; and Jane G. Allen Special Projects Editor This note is available in Vanderbilt Law Review: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol34/iss3/4 SPECIAL PROJECT Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 657 II. PERMANENT ADMISSION TO THE BAR ................. 661 A. Good Moral Character ....................... 664 1. Due Process--The Analytical Framework... 666 (a) Patterns of Conduct Resulting in a Finding of Bad Moral Character:Due Process Review of Individual Deter- minations ........................ -

First Amendment

FIRST AMENDMENT RELIGION AND FREE EXPRESSION CONTENTS Page Religion ....................................................................................................................................... 1063 An Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1063 Scholarly Commentary ................................................................................................ 1064 Court Tests Applied to Legislation Affecting Religion ............................................. 1066 Government Neutrality in Religious Disputes ......................................................... 1070 Establishment of Religion .................................................................................................. 1072 Financial Assistance to Church-Related Institutions ............................................... 1073 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Released Time ...... 1093 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Prayers and Bible Reading ..................................................................................................................... 1094 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Curriculum Restriction ................................................................................................................ 1098 Access of Religious Groups to Public Property ......................................................... 1098 Tax Exemptions of Religious Property ..................................................................... -

BOROUGH of DURYEA V. GUARNIERI

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2010 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BOROUGH OF DURYEA, PENNSYLVANIA, ET AL. v. GUARNIERI CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT No. 09–1476. Argued March 22, 2011—Decided June 20, 2011 After petitioner borough fired respondent Guarnieri as its police chief, he filed a union grievance that led to his reinstatement. When the borough council later issued directives instructing Guarnieri how to perform his duties, he filed a second grievance, and an arbitrator or- dered that some of the directives be modified or withdrawn. Guarni- eri then filed this suit under 42 U. S. C. §1983, alleging that the di- rectives were issued in retaliation for the filing of his first grievance, thereby violating his First Amendment “right . to petition the Gov- ernment for a redress of grievances”; he later amended his complaint to allege that the council also violated the Petition Clause by denying his request for overtime pay in retaliation for his having filed the §1983 suit. The District Court instructed the jury, inter alia, that the suit and the grievances were constitutionally protected activity, and the jury found for Guarnieri. -

First Amendment

FIRST AMENDMENT RELIGION AND EXPRESSION CONTENTS Page Religion ....................................................................................................................................... 1013 An Overview ........................................................................................................................ 1013 Scholarly Commentary ................................................................................................ 1014 Court Tests Applied to Legislation Affecting Religion ............................................. 1016 Government Neutrality in Religious Disputes .......................................................... 1020 Establishment of Religion .................................................................................................. 1022 Financial Assistance to Church-Related Institutions ............................................... 1022 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Released Time ....... 1043 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Prayers and Bible Reading ..................................................................................................................... 1044 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Curriculum Re- striction ..................................................................................................................... 1048 Access of Religious Groups to School Property ......................................................... 1048 Tax Exemptions of Religious Property ..................................................................... -

Foreword: Evaluating the Work of the New Libertarian Supreme Court John E

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 7 Article 1 Number 2 Winter 1980 1-1-1980 Foreword: Evaluating the Work of the New Libertarian Supreme Court John E. Nowak Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation John E. Nowak, Foreword: Evaluating the Work of the New Libertarian Supreme Court, 7 Hastings Const. L.Q. 263 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol7/iss2/1 This Constitutional Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foreword: Evaluating the Work of the New Libertarian Supreme Court By JOHN E. NOWAK* Introduction Another Term of the Supreme Court has come and gone, leaving few surprises in its wake. As with most recent Terms, one could have guessed in advance the topics, outcomes, and voting divisions for most of the cases: racial minority groups will win, but not very much;' aliens, illegitimates, and women will win only when laws are shock- ingly open in their discrimination against them;2 some procedural pro- tection will be given to those who have a clearly defined liberty or property interest at stake in a government proceeding 3 (but not to others);4 fundamental rights such as voting or privacy will not be ex- tended,5 except for a woman's right to an abortion;6 poor people will * Professor of Law, University of Illinois College of Law. -

Annotated Wisconsin Constitution

ANNOTATED WISCONSIN CONSTITUTION ANNOTATED WISCONSIN CONSTITUTION LAST AMENDED AT THE APRIL 2015 ELECTION. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 14, 2016. PREAMBLE 12. Ineligibility of legislators to office. 13. Ineligibility of federal officers. ARTICLE I. 14. Filling vacancies. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS. 15. Exemption from arrest and civil process. Section 16. Privilege in debate. 1. Equality; inherent rights. 17. Enactment of laws. 2. Slavery prohibited. 18. Title of private bills. 3. Free speech; libel. 19. Origin of bills. 4. Right to assemble and petition. 20. Yeas and nays. 5. Trial by jury; verdict in civil cases. 21. Repealed. 6. Excessive bail; cruel punishments. 22. Powers of county boards. 7. Rights of accused. 23. Town and county government. 8. Prosecutions; double jeopardy; self−incrimination; bail; habeas 23a. Chief executive officer to approve or veto resolutions or ordinances; corpus. proceedings on veto. 9. Remedy for wrongs. 24. Gambling. 9m. Victims of crime. 25. Stationery and printing. 10. Treason. 26. Extra compensation; salary change. 11. Searches and seizures. 27. Suits against state. 12. Attainder; ex post facto; contracts. 28. Oath of office. 13. Private property for public use. 29. Militia. 14. Feudal tenures; leases; alienation. 30. Elections by legislature. 15. Equal property rights for aliens and citizens. 31. Special and private laws prohibited. 16. Imprisonment for debt. 32. General laws on enumerated subjects. 17. Exemption of property of debtors. 33. Auditing of state accounts. 18. Freedom of worship; liberty of conscience; state religion; public funds. 34. Continuity of civil government. 19. Religious tests prohibited. 20. Military subordinate to civil power. ARTICLE V. 21. Rights of suitors. EXECUTIVE. 22.