The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: the Gentile V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

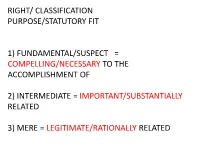

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

Attorney Solicitation: the Scope of State Regulation After <Em>Primus</Em> and <Em>Ohralik</Em>

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 12 1978 Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik David A. Rabin University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Profession Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Rabin, Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik, 12 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 144 (1978). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol12/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTORNEY SOLICITATION: THE SCOPE OF STATE REGULATION AFTER PRIMUS AND OHRALIK Within the past few years, there has been a growing concern both within and without the legal profession-over increasing the layman's access to legal services. Two of the principal means of increasing this access, advertising and solicitation, 1 have long been prohibited by the organized bar, although a few minor exceptions have been allowed. In lff77, the question of the constitutionality of prohibitions against legal advertising was presented to the United States Supreme Court in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona. 2 The Court ruled in a landmark decision that certain types of advertising could not be prohibited, but expressly reserved the question of the con stitutionality of prohibitions against in-person solicitation.3 Eleven months after Bates, the Court decided two attorney solicitation cases, In re Primus4 and Ohra/ik v. -

Exceptions to the First Amendment

Order Code 95-815 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Updated July 29, 2004 Henry Cohen Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Summary The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press....” This language restricts government both more and less than it would if it were applied literally. It restricts government more in that it applies not only to Congress, but to all branches of the federal government, and to all branches of state and local government. It restricts government less in that it provides no protection to some types of speech and only limited protection to others. This report provides an overview of the major exceptions to the First Amendment — of the ways that the Supreme Court has interpreted the guarantee of freedom of speech and press to provide no protection or only limited protection for some types of speech. For example, the Court has decided that the First Amendment provides no protection to obscenity, child pornography, or speech that constitutes “advocacy of the use of force or of law violation ... where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Court has also decided that the First Amendment provides less than full protection to commercial speech, defamation (libel and slander), speech that may be harmful to children, speech broadcast on radio and television, and public employees’ speech. -

Professional Licensure General Disclosure Juris Doctor

Last Updated: 8/17/2020 Professional Licensure General Disclosure Juris Doctor In accordance with 34 C.F.R. §668.43, and in compliance with the requirements outlined in the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (SARA) Manual, DePaul University provides the following disclosure related to the educational requirements for professional licensure and certification1. This disclosure is strictly limited to the University’s determination of whether its educational program, Juris Doctor, if successfully completed, would be sufficient to meet the educational licensure or certification requirements in a State for a licensed attorney.2 DePaul cannot provide verification of an individual’s ability to meet licensure or certification requirements unrelated to its educational programming. This disclosure does not provide any guarantee that any particular state licensure or certification entity will approve or deny your application. Furthermore, this disclosure does not account for changes in state law or regulation that may affect your application for licensure and occur after this disclosure has been made. Enrolled students and prospective students are strongly encouraged to contact their State’s licensure entity using the links provided to review all licensure and certification requirements imposed by their state(s) of choice. DePaul University has designed an educational program curriculum for a Juris Doctor, that if successfully completed is sufficient to meet the licensure and certification requirements for a licensed attorney in the following -

Message from the President

NEVADA LAWYER EDITORIAL BOARD Patricia D. Cafferata, Chair Scott McKenna Message from Michael T. Saunders, Chair-Elect Gregory R. Shannon Richard D. Williamson, Vice Chair Stephen F. Smith Mark A. Hinueber, Immediate Past Chair Beau Sterling Erin Barnett Kristen E. Simmons Hon. Robert J. Johnston Scott G. Wasserman the President Lisa Wong Lackland John Zimmerman Frank Flaherty, Esq., State Bar of Nevada President BOARD OF GOVERNORS President: Frank Flaherty, Carson City President Elect: Alan Lefebvre, Las Vegas DUES TALK Vice President: Elana Graham “I will not make any broad promises to you on Immediate Past President: Constance Akridge, Las Vegas behalf of the board, beyond stating that we do not anticipate a dues increase within the Paola Armeni, Las Vegas Mason Simons, Elko Elizabeth Brickfield, Las Vegas Hon. David Wall (Ret.), next few years and that the board and staff Laurence Digesti, Reno Las Vegas Eric Dobberstein, Las Vegas Ex-Officio will continue to work diligently to control costs Vernon (Gene) Leverty, Reno Interim Dean and to be smart with your dues dollars.” Paul Matteoni, Reno Nancy Rapoport, Ann Morgan, Reno UNLV Boyd School of Law Richard Pocker, Las Vegas Richard Trachok, Chair October always seems to be a good time to talk about money. At the last Bryan Scott, Las Vegas Board of Bar Examiners Richard Scotti, Las Vegas meeting of the Board of Governors (BOG), we spent some time discussing your licensing fees, typically referred to as “dues.” I am happy to report that STATE BAR STAFF the State Bar of Nevada is in good shape, fiscally and otherwise. -

Legal Job Board Network - Network Members

Legal Job Board Network - Network Members • ACBA Job Board • Albuquerque Bar Association • American Health Law Association • Arizona Attorney Magazine Career Center • Association for Conflict Resolution • Atlanta Bar Association • Bar Association of Lehigh County • Bar Association of Montgomery County Maryland • BASF Career Center • Boston Bar Association • BPLA Career Center • California Alliance of Paralegal Associations • CBA Career Center • Clearwater Bar Association • Cleveland Metropolitan Bar Association • DBA Career Center • DeKalb Bar Association • District of Columbia Bar Career Center • DuPage County Bar Association • Fayette County Bar Association • Grand Rapids Bar Association • Hennepin County Bar Association • Hillsborough County Bar Association • Illinois Chapter of National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys • Illinois Defense Counsel Career Center • Illinois State Bar Association Career Center • ISBA Career Center • Jacksonville Bar Association • Johnson County Bar Association • Kansas Bar Association • KBA Career Center • King County Bar Association • LA Legal Jobs • LAPA Career Center • Lawyers Without Borders (LWOB) • Macomb County Bar Association • Maine State Bar Association • Maricopa County Bar Association • Maryland Association of Paralegals • Milwaukee Bar Association • Minnesota Paralegal Association • Mississippi Bar Job Board • MSBA Career Center • NALS Career Center • Nashville Bar Association • National Capital Area Paralegal Association (NCAPA) • National Creditors Bar Association • NCBA Career Center • NCBA -

Admission to the Bar: a Constitutional Analysis

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Issue 3 - April 1981 Article 4 4-1981 Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis Ben C. Adams Edward H. Benton David A. Beyer Harrison L. Marshall, Jr. Carter R. Todd See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Ben C. Adams; Edward H. Benton; David A. Beyer; Harrison L. Marshall, Jr.; Carter R. Todd; and Jane G. Allen Special Projects Editor, Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis, 34 Vanderbilt Law Review 655 (1981) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol34/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis Authors Ben C. Adams; Edward H. Benton; David A. Beyer; Harrison L. Marshall, Jr.; Carter R. Todd; and Jane G. Allen Special Projects Editor This note is available in Vanderbilt Law Review: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol34/iss3/4 SPECIAL PROJECT Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 657 II. PERMANENT ADMISSION TO THE BAR ................. 661 A. Good Moral Character ....................... 664 1. Due Process--The Analytical Framework... 666 (a) Patterns of Conduct Resulting in a Finding of Bad Moral Character:Due Process Review of Individual Deter- minations ........................ -

First Amendment

FIRST AMENDMENT RELIGION AND FREE EXPRESSION CONTENTS Page Religion ....................................................................................................................................... 1063 An Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1063 Scholarly Commentary ................................................................................................ 1064 Court Tests Applied to Legislation Affecting Religion ............................................. 1066 Government Neutrality in Religious Disputes ......................................................... 1070 Establishment of Religion .................................................................................................. 1072 Financial Assistance to Church-Related Institutions ............................................... 1073 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Released Time ...... 1093 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Prayers and Bible Reading ..................................................................................................................... 1094 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Curriculum Restriction ................................................................................................................ 1098 Access of Religious Groups to Public Property ......................................................... 1098 Tax Exemptions of Religious Property ..................................................................... -

PABLE Certificate of Good Standing Repository List

CERTIFICATE OF GOOD STANDING CONTACT LIST Current as of May, 2019 This list is being provided only to assist you in your search It is your obligation to confirm the requirements with the jurisdiction issuing the Certificate of Good Standing ALABAMA COLORADO GEORGIA INDIANA Supreme Court of Alabama Ralph L. Carr Judicial Center Supreme Court of Georgia Clerk of the Supreme Court Office Supreme Court Clerk Colorado Supreme Court 244 Washington Street, SW Roll of Attorneys Administrator COGS Request Office of Attorney Registration Rm. 572 402 West Washington Street 300 Dexter Avenue 1300 Broadway, Suite 510 Atlanta, GA 30334 Room W062 Montgomery, AL 36104 Denver, CO 80203 (404) 656-3470 Indianapolis, IN 46204 (334) 229-0700 (303) 928-7800 (404) 656-2253 Fax (317) 232-5861, ext. 4 Fee: $15 Fee: $10, CC or MO payable to Fee: $10 Fee: $2, payable to the Clerk of http://judicial.alabama.gov/appellate Clerk of Supreme Court, Written request include SASE Courts w/ SASE call or send a /cogs send written request include SASE. https://www.gasupreme.us/court- written request http://coloradosupremecourt.com/C %20information/purchase/ https://courts- ALASKA urrent%20Lawyers/DocumentRequ ingov.zendesk.com/hc/en- Clerk of Appellate Courts ests.asp GUAM us/articles/115005248968-How-do- 303 K Street Supreme Court of Guam I-obtain-an-attorney-Certificate-of- Anchorage, AK 99501 Board of Law Examiners Good-Standing- CONNECTICUT (907) 264-0608 / 0612 Suite 300, Guam Judicial Center Clerk of the Superior Court Fee: no charge, written request for 120 W. O'Brien Drive Hartford Judicial District IOWA Supreme Court issued certificate Hagåtña, GU 96910 95 Washington Street Clerk of Supreme Court https://alaskabar.org/for- (671) 475-3120 / 3180 Hartford, CT 06106 1111 E. -

Crowe V. Oregon State Bar

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DANIEL Z. CROWE; LAWRENCE K. No. 19-35463 PETERSON I; OREGON CIVIL LIBERTIES ATTORNEYS, an Oregon D.C. No. nonprofit corporation, 3:18-cv-02139- Plaintiffs-Appellants, JR v. OREGON STATE BAR, a Public Corporation; OREGON STATE BAR BOARD OF GOVERNORS; VANESSA A. NORDYKE, President of the Oregon State Bar Board of Governors; CHRISTINE CONSTANTINO, President- elect of the Oregon State Bar Board of Governors; HELEN MARIE HIERSCHBIEL, Chief Executive Officer of the Oregon State Bar; KEITH PALEVSKY, Director of Finance and Operations of the Oregon State Bar; AMBER HOLLISTER, General Counsel for the Oregon State Bar, Defendants-Appellees. 2 CROWE V. OREGON STATE BAR DIANE L. GRUBER; MARK RUNNELS, No. 19-35470 Plaintiffs-Appellants, D.C. No. v. 3:18-cv-01591- JR OREGON STATE BAR; CHRISTINE CONSTANTINO; HELEN MARIE HIERSCHBIEL, OPINION Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Oregon Michael H. Simon, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted May 12, 2020 Portland, Oregon Filed February 26, 2021 Before: Jay S. Bybee and Lawrence VanDyke, Circuit Judges, and Kathleen Cardone,* District Judge. Per Curiam Opinion; Partial Concurrence and Partial Dissent by Judge VanDyke * The Honorable Kathleen Cardone, United States District Judge for the Western District of Texas, sitting by designation. CROWE V. OREGON STATE BAR 3 SUMMARY** Civil Rights The panel affirmed in part and reversed in part the district court’s dismissal of plaintiffs’ claims, and remanded, in actions alleging First Amendment violations arising from the Oregon State Bar’s requirement that lawyers must join and pay annual membership fees in order to practice in Oregon.