First Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VAGUENESS PRINCIPLES Carissa Byrne Hessick*

VAGUENESS PRINCIPLES Carissa Byrne Hessick ABSTRACT Courts have construed the right to due process to prohibit vague criminal statutes. Vague statutes fail to give sufficient notice, lead to arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement, and represent an unwarranted delegation to law enforcement. But these concerns are hardly limited to prosecutions under vague statutes. The modern expansion of criminal codes and broad deference to prosecutorial discretion imperil the same principles that the vagueness doctrine was designed to protect. As this Essay explains, there is no reason to limit the protection of these principles to vague statutes. Courts should instead revisit current doctrines which regularly permit insufficient notice, arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement, and unwarranted delegations in the enforcement of non-vague criminal laws. I. INTRODUCTION Last term, in Johnson v. United States, the Supreme Court held that a portion of the Armed Career Criminal Act was unconstitutionally vague.1 This is the second time in five years that the Court has used the vagueness doctrine to strike down or significantly limit a criminal statute.2 The void-for- vagueness doctrine is hardly a new invention. Since 1914,3 the Court has Anne Shea Ransdell and William Garland "Buck" Ransdell, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Law, University of North Carolina School of Law. J.D., Yale Law School; B.A., Columbia University. I would like to thank Shima Baradaran Baughman, Rick Bierschbach, Jack Chin, Beth Colgan, Paul Crane, Dan Epps, Andy Hessick, Ben Levin, Richard Meyers, Ion Meyn, Eric Miller, Larry Rosenthal, Meghan Ryan, John Stinneford, and Mark Weidemaier for their helpful comments on this project. -

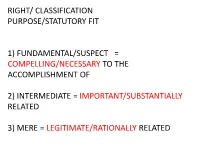

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

Petitioner, V

No. 19-___ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________ MARK JANUS, Petitioner, v. AMERICAN FEDERATION OF STATE, COUNTY, AND MUNICIPAL EMPLOYEES, COUNCIL 31, ET AL., Respondents. _________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit _________ PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI _________ JEFFREY M. SCHWAB WILLIAM L. MESSENGER LIBERTY JUSTICE CENTER Counsel of Record 190 South LaSalle Street AARON B. SOLEM Suite 1500 c/o NATIONAL RIGHT TO Chicago, IL 60603 WORK LEGAL DEFENSE (312) 263-7668 FOUNDATION, INC. 8001 Braddock Road Suite 600 Springfield, VA 22160 (703) 321-8510 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner QUESTION PRESENTED Is there a “good faith defense” to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 that shields a defendant from damages liability for de- priving citizens of their constitutional rights if the de- fendant acted under color of a law before it was held unconstitutional? (i) ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS AND RULE 29.6 STATEMENT Petitioner, a Plaintiff-Appellant in the court below, is Mark Janus. Respondents, Defendants-Appellees in the court be- low, are American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31; Simone McNeil, in her official capacity as the Acting Director of the Illi- nois Department of Central Management Services; and Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul. Other parties to the original proceedings below who are not Petitioners or Respondents include plaintiffs Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner, Brian Trygg, and Ma- rie Quigley, and defendant General Teamsters/Profes- sional & Technical Employees Local Union No. 916. Because no Petitioner is a corporation, a corporate disclosure statement is not required under Supreme Court Rule 29.6. -

Federal Courts, Overbreadth, and Vagueness: Guiding Principles for Constitution Challenges to Uninterpreted State Statutes

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2002 Federal Courts, Overbreadth, and Vagueness: Guiding Principles for Constitution Challenges to Uninterpreted State Statutes Mark L. Rienzi The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Stuart Buck Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Mark L. Rienzi & Stuart Buck, Federal Courts, Overbreadth, and Vagueness: Guiding Principles for Constitution Challenges to Uninterpreted State Statutes, 2002 Utah L. Rev. 381. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Courts, Overbreadth, and Vagueness: Guiding Principles for Constitutional Challenges to Uninterpreted State Statutes Stuart Buck* and Mark L. Rienzi** I. INTRODUCTION When a state statute is challenged in federal court as unconstitutionally overbroad or vague, the federal court is caught between two fundamental principles of constitutional law. On the one hand, federal courts have been instructed numerous times that they should invalidate a state statute only when there is no other choice. The Supreme Court has noted that it is a "cardinal principle" of statutory interpretation that a federal court must accept any plausible interpretation such that a state statute need not be invalidated. Moreover, the doctrines of abstention, certification, and severance all exist in order to show deference to a state's power to interpret its own laws and to allow as much of a state law to survive as possible. -

Reopening the Public Forum--From Sidewalks to Cyberspace

01O STATE LAW JOURNAL Volume 58, Number 5, 1998 Reopening the Public Forum-From Sidewalks to Cyberspace STEVEN G. GEY* The publicforum doctrine has been afxture offree speech law since the beginning of the modem era of First Amendment jurisprudence. The doctrine serves several functions. It is a metaphorical reference point for the strong protection offree speech everywhere, and it provides specific rules protecting free speech in public places. In this Article, Professor Gey reviews the development of the public forum doctrine. Professor Gey argues that serious problems have developed within the doctrine in recent times due to the Supreme Court's refusal to extend the fidl protection of the doctrine to new forwms that do not resemble the parks and sidewalks of the traditionalpublic forum cases. Professor Gey then reviews Justice Kennedy's recent contributions to the debate over the public forum doctrine, in which Justice Kennedy advocates erpanding the protective scope of the doctrine. Professor Gey draws on Kennedy's suggestions to propose a reinterpretationof public forum doctrine. Under this reinterpretation, the First Amendment would protect speech in a public space unless the speech would significantly interfere with the government's noncommunicative activities in that space. Professor Gey also argues that the reinterpreteddoctrine should extend beyond physical spaces to cover "metaphysical"forums, including any government property that provides an instrunentalty of communication. In the final sections of the Article, Professor Gey considers the application of his theory to two new, "metaphysical"forums: government subsidy programs and government access to the Internet. In many respects, the story of the First Amendment is the story of the public forum doctrine. -

AAUP Annual Legal Update August, 2020

AAUP Annual Legal Update August, 2020 Aaron Nisenson, Senior Counsel American Association of University Professors I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 II. First Amendment and Speech Rights ...................................................................................... 5 A. Garcetti / Citizen Speech ......................................................................................................... 5 Lane v. Franks, 134 S. Ct. 2369 (2014) .................................................................................. 5 B. Faculty Speech ......................................................................................................................... 5 Demers v. Austin, 746 F.3d 402 (9th Cir. 2014) .................................................................... 5 Wetherbe v. Tex. Tech Univ. Sys., 699 F. Appx 297 (5th Cir. 2017); Wetherbe v. Goebel, No. 07-16-00179-CV, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 1676 (Mar. 6, 2018) ................................... 5 Buchanan v. Alexander, 919 F.3d 847 (5th Cir. March 22, 2019) ......................................... 6 EXECUTIVE ORDER, Improving Free Inquiry, Transparency, and Accountability at Colleges and Universities (D. Trump March 21, 2019) ........................................................ 8 C. Union Speech............................................................................................................................ 9 Meade v. Moraine Valley Cmty. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

19-267 Our Lady of Guadalupe School V. Morrissey-Berru (07/08/2020)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2019 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL v. MORRISSEY- BERRU CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–267. Argued May 11, 2020—Decided July 8, 2020* The First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions “to de- cide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.” Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral of Russian Orthodox Church in North America, 344 U. S. 94, 116. Applying this principle, this Court held in Hosanna- Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, 565 U. S. 171, that the First Amendment barred a court from entertaining an employment discrimination claim brought by an elementary school teacher, Cheryl Perich, against the religious school where she taught. Adopting the so-called “ministerial exception” to laws governing the employment relationship between a religious institution and certain key employees, the Court found relevant Perich’s title as a “Minister of Religion, Commissioned,” her educational training, and her respon- sibility to teach religion and participate with students in religious ac- tivities. Id., at 190–191. -

The First Amendment in Its Forgotten Years

The First Amendment in Its Forgotten Years David M. Rabbant TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Free Speech Before the Courts 522 A. Supreme Court Cases 524 I. Avoiding First Amendment Issues 525 Resisting Incorporation into the Fourteenth Amendment 525 Excluding Publications from the Mails 526 Neglecting First Amendment Issues 529 Limiting the Meaning of Speech 531 2. Addressing First Amendment Issues 533 Justice Holmes and the Bad Tendency of Speech 533 Review of Statutes Penalizing Speech 536 The First Amendment as the Embodiment of English Common Law 539 3. Hints of Protection 540 4. Summary 542 B. Decisions Based on State Law 543 1. The Bad Tendency Doctrine 543 Speech by Radicals 543 Obscenity and Public Morals 548 2. Libel 550 3. Political Speech 551 4. Labor Injunctions 553 5. Speech in Public Places 555 C. The Judicial Tradition 557 t Counsel, American Association of University Professors. 514 Prewar Free Speech II. Legal Scholarship 559 A. The Social Interest in Free Speech 563 B. The Distinction Between Public and Private Speech 564 1. Schofield's Formulation of the Distinction 564 2. Other Scholarly Support for the Distinction 566 C. The Expanding Conception of Free Speech 568 D. The Rejection of Blackstone 570 E. The Limits of Protected Speech 572 1. The Direct Incitement Test 572 2. Pound's Balancing Test 575 3. Schroeder's Test of Actual Injury 576 4. The Benefits of LibertarianStandards 578 F. The Heritage of Prewar Scholarship 579 III. The Role of the Prewar Tradition in the Early Develop- ment of Modern First Amendment Doctrine 579 A. -

Court Order Enjoining Local DBE Program

Case 1:07-cv-00019-BAE-WLB Document 19 Filed 03/14/07 Page 1 of 10 FILED E ,!"T COURT UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 0 V. SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA AUGUSTA DIVISIO N 7 !T 1 4 P}1 3: 32 THOMPSON BUILDING WRECKING COMPANY, INC., PAULETTE TUCKER ENTERPRISES, INC., ;~J; C L d/b/a TUCKER GRADING AND HAULING, S0. D S) -. OF GA . RICHARD CALDWELL, d/b/a CLASSIC ROCK HAULING, SIDNEY CULLARS, d/b/a SIDNEY CULLARS TRUCKING, The plaintiffs allege that prime contract bids Plaintiffs , containing DBE participation at the subcontract level are treated more favorably than bids V. 107CV019 without DBE participation at the subcontract ; in other words, the DBE Program AUGUSTA, GEORGIA, level encourages prime contractors to discriminate Defendant. against subcontractors on the basis of race, gender, and relative economic advantage . Doc. ORDER # 1 at 14-15 ; see doc. # 5, exh. C at 1-66 (AUGUSTA CODE § 1-10-62(b)(9)) ; see also doc. 1. INTRODUCTIO N # 13 at 1 (the parties have stipulated that the City currently adds up to "20 points" to a In this civil rights action, various plaintiffs proposal or bid that utilizes DBEs) . According challenge the City of Augusta, Georgia's Disadvantaged Business Enterprises ("DBE") Program as unconstitutionally discriminatory. Doc. # 1 . They claim that the Program violates for a project to demolish the Candy Factory Buildings in Augusta . See doc. # 1 at 5-8 (describing facts surrounding the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth the bidding for the Candy Factory Buildings demolition Amendment to the United States Constitution, as contract) . -

Judicial Acquiescence in the Forfeiture of Constitutional Rights Through Expansion of the Conditioned Privilege Doctrine

Indiana Law Journal Volume 28 Issue 4 Article 4 Summer 1953 Judicial Acquiescence in the Forfeiture of Constitutional Rights through Expansion of the Conditioned Privilege Doctrine Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation (1953) "Judicial Acquiescence in the Forfeiture of Constitutional Rights through Expansion of the Conditioned Privilege Doctrine," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 28 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol28/iss4/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA LAW JOURNAL from detruction by Communism, there is vital need to salvage consti- tutionally guaranteed rights from annihilation by these same efforts. Both courts and legislatures should re-examine the Communist threat and should then determine whether recent laws do themselves present more of a threat to our freedom than does subversion. JUDICIAL ACQUIESCENCE IN THE FORFEITURE OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS THROUGH EXPANSION OF THE CONDITIONED PRIVILEGE DOCTRINE Mr. Justice Douglas, dissenting in Adler v. Board of Education of the City of New York, declared: "I have not been able to accept the recent doctrine that a citizen who enters the public service can be forced to sacrifice his civil rights. I cannot for example find in our constitutional scheme the power of the state to place its employees in the category of second class citizens by denying them freedom of thought and expres- sion."' It is both surprising and noteworthy that Mr.