Free Speech for Lawyers W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

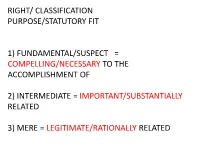

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

The Citizen Lawyer: a Brief Informal History of a Myth with Some Basis

THE CITIZEN LAWYER-A BRIEF INFORMAL HISTORY OF A MYTH WITH SOME BASIS IN REALITY ROBERT W. GORDON* The term "citizen lawyer" seems to be shorthand for a complex assortment of social types, but the core meaning is plain enough. The citizen lawyer is a lawyer who acts in a significant part of his or her professional life with some plausible vision of the public good and the general welfare in mind. Of course, citizen lawyers, like most lawyers, may seek wealth, power, fame, and reputation for themselves. They may also represent and further the ends of clients with distinctly selfish or antisocial interests. What makes them citizen lawyers, then, is that they also devote time and effort to public ends and values: the service of the Republic, their communi- ties, the ideal of the rule of law, and reforms to enhance the law's efficiency, fairness, and accessibility.' So general and bland a definition would, I expect, command agreement from most lawyers. But it covers up deep divisions among the views that lawyers have traditionally held on the proper scope of their public or civic obligations. American lawyers' starting point for conventional reasoning about these roles, more or less a constant throughout its history, is like that of professions of advocates elsewhere: that lawyers effectively produce the public goods of justice and the rule of law by just doing their regular day jobs, zealously serving their clients.2 * Chancellor Kent Professor of Law and Legal History, Yale University. 1. See W. Taylor Reveley III, The Citizen Lawyer, 50 WM. -

Vue Musicale NME

Sziget 2009: Une sélection très subjective… Par JFB le lun 10/08/2009 - 12:32 10 août Tankcsapda (lire l'article ci-dessus) 11 août Soirée RAR (Rock Against Racism) alias biZARE (Zene a Rasszizmus Ellen) En 1976, après certaines déclarations provocatrices de David Bowie et Eric Clapton, le mouvement RAR est créé et organise un premier concert pour lutter contre la montée du racisme en Grande Bretagne. Bien que ceux-ci se soient excusés par la suite, le mouvement a continué à défendre des valeurs de tolérance et de compréhension mutuelle par l’organisation de concerts et festivals, auxquels public et artistes (The Clash, The Buzzcocks, etc.) ont afflué. Relancé en 2002 par une série de concerts “Love Music Hate Racism”, le mouvement RAR a rencontré le soutien des artistes Damon Albarn, Kaiser Chiefs, Asian Dub Foundation. Que cette première journée rayonne sur tout le festival ! 12 août Nouvelle Vague 16:30 - Grande Scène Le projet de Nouvelle Vague est de réarranger de façon personnelle les plus grands titres post punk du début des années 1980 qui sont très rarement repris car jamais vraiment considérés comme de vraies chansons. Puis par la suite les titres sont réarrangés en suivant une autre idée: les sonorités des caraïbes entre 1940 et 1970, soit le ska/rocksteady, le reggae, le calypso, la salsa cubaine, le vaudou haitien, etc. D'où des arrangements et orchestrations très colorées, beaucoup de percussions, des guitares acoustiques et des voix féminines, mais aussi un chanteur, de l'accordéon, du steel drum etc. Nouvelle Vague reprend les titres de grands groupes emblématiques comme Bauhaus ou Siouxsie, aussi bien que des pépites oubliées. -

The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: the Gentile V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 43 1993 The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision Suzanne F. Day Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Suzanne F. Day, The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision, 43 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1347 (1993) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol43/iss4/43 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE SUPREME COURT'S AITACK ON ATTORNEYS' FREEDOM OF ExPRESSION: THE GENTILE v. STATE BAR OF NEVADA DECISION TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............. ............ 1349 A. The Dilemma of the Defense Attorney ....... 1349 B. State Court Rules Restricting Attorney Communication with the Media ............. 1350 11. CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS RAISED BY RESTRICTING PRETRIAL PUBLICITY THROUGH CURBING THE SCOPE OF ATrORNEY SPEECH: THE FAIR TRIAL - FREE PRESS DEBATE ...... ........................ 1351 A. The Sheppard v. Maxwell Decision: The United States Supreme Court's Directive to Trial Court Judges ............................ 1352 B. The Conflicting First Amendment Rights of Attorneys, Sixth Amendment Rights of the Defendant, and the State and Public Interest in the Impartial Administration of Justice ........... 1355 1. What the Amendments Guarantee ......... 1355 2. -

Attorney Solicitation: the Scope of State Regulation After <Em>Primus</Em> and <Em>Ohralik</Em>

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 12 1978 Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik David A. Rabin University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Profession Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Rabin, Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik, 12 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 144 (1978). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol12/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTORNEY SOLICITATION: THE SCOPE OF STATE REGULATION AFTER PRIMUS AND OHRALIK Within the past few years, there has been a growing concern both within and without the legal profession-over increasing the layman's access to legal services. Two of the principal means of increasing this access, advertising and solicitation, 1 have long been prohibited by the organized bar, although a few minor exceptions have been allowed. In lff77, the question of the constitutionality of prohibitions against legal advertising was presented to the United States Supreme Court in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona. 2 The Court ruled in a landmark decision that certain types of advertising could not be prohibited, but expressly reserved the question of the con stitutionality of prohibitions against in-person solicitation.3 Eleven months after Bates, the Court decided two attorney solicitation cases, In re Primus4 and Ohra/ik v. -

2 Punk – Eine Einleitung

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen“ >Band 1 von 1< Verfasser Armin Wilfling angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. A 316 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Musikwissenschaft Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Dr. Emil Lubej Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen, Armin Wilfling Seite 2 1 KURZBESCHREIBUNGEN...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ........................................................................................... 7 1.2 ENGLISH ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 7 2 PUNK – EINE EINLEITUNG.................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 STILDEFINIERENDE MERKMALE DES PUNKS ......................................................................................... 9 2.2 LESEANLEITUNG ................................................................................................................................. 13 3 PUNK – EINE GESCHICHTE ................................................................................................................ 15 3.1 URSPRÜNGE UND VORLÄUFER ............................................................................................................ 17 3.1.1 Garage Rock................................................................................................................................. -

The Construction of Hip Hop Identities in Finnish Rap Lyrics Through English and Language Mixing

UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING A Pro Gradu Thesis in English by Elina Westinen Department of Languages 2007 HUMANISTINEN TIEDEKUNTA KIELTEN LAITOS Elina Westinen ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING Pro gradu –tutkielma Englannin kieli Joulukuu 2007 141 sivua Englannin kielen rooli ja asema maailmankielenä on kiistaton, ja Suomessakin englannin kieltä käytetään monilla eri aloilla. Juuriltaan amerikkalaisesta hip hop – kulttuuristakin on viime vuosina kasvanut globaali nuorisokulttuuri, joka on saavuttanut pysyvän aseman Suomessa. Tämän tutkimuksen tarkoituksena on selvittää, miten hip hop –identiteetti rakentuu suomalaisissa rap–lyriikoissa. Päätavoitteena on tutkia, millainen hip hop –identiteetti muodostuu lyriikoiden englannin kielen ja kielten sekoittumisen (suomi ja englanti) kautta. Tutkimuksen aineistona käytetään kolmen eri hip hop –artistin ja – ryhmän (Cheek, Sere & SP ja Kemmuru) lyriikoita 2000-luvulta. Niiden pääkieli on suomi, mutta kaikissa kappaleissa on myös englanninkielisiä elementtejä. Sanojen tarkkojen alkuperien sekä muun tiedon selvittämiseksi olen tarvittaessa konsultoinut itse artisteja. Analyysissä identiteetin käsitetään rakentuvan osaltaan kielen avulla. Identiteetti rakentuu diskursseissa, ja se on muuttuva ja monitahoinen. Aineiston analyysissä kielenvaihtelu ymmärretään joko a) kielten sekoittumisena, josta syntyy kokonaan uusi kieli/kielellinen tyyli tai b) koodinvaihtona, joka on merkityksellistä diskurssin paikallisella tasolla. Tulokset osoittavat, että rap–lyriikoissa pikemminkin sekoitetaan suomen ja englannin kieltä (language mixing) kuin vaihdetaan koodia. Näin ollen muodostuu uusi, suomalaisille rap–lyriikoille ominainen kieli ja tyyli. Usein hip hop -englannin sanoja ja fraaseja taivutetaan suomen ortografian, morfologian tai molempien mukaan. Joskus lyriikoissa esiintyy myös ns. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

Peace Punks and Punks Against Racism: Resource Mobilization and Frame Construction in the Punk Movement

Music and Arts in Action | Volume 2 | Issue 1 PEACE PUNKS AND PUNKS AGAINST RACISM: RESOURCE MOBILIZATION AND FRAME CONSTRUCTION IN THE PUNK MOVEMENT MIKE ROBERTS & RYAN MOORE Department of Sociology | San Diego State University | USA* Department of Sociology | Florida Atlantic University | USA ABSTRACT In recent years, scholars have begun to attend to the gap in our understanding of the relationship between music and social movements. One such example is Corte’s and Edwards’ “White Power Music and the Mobilization of Racist Social Movements.” Our research shares the perspective of Corte and Edwards (2008) which emphasizes the centrality of music to social movement organizations, especially in terms of resource mobilization, but rather than look at how punk music was used as an instrument by an external social movement like the White Power movement, we look at how punks themselves joined social movements and altered the dynamics of the movements they joined. We also provide examples of punk involvement in left wing social movements to emphasize the indeterminate nature of punk politics. We examine two such cases: the Rock Against Racism movement in the U.K., and the Peace movement in the U.S. In both cases, punks made use of their independent media as a means to provide an infrastructure for mobilization of resources to sustain the punks’ involvement in these social movements and the unique framing provided by punks, which altered the dynamic of the movements they joined. What makes punk an interesting case is that the “do-it-yourself” ethic of independent media construction that was at the centre of the punk movement made it possible for punks to make connections to various other social movements as well as alter the dynamics of those social movements. -

Exceptions to the First Amendment

Order Code 95-815 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Updated July 29, 2004 Henry Cohen Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Summary The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press....” This language restricts government both more and less than it would if it were applied literally. It restricts government more in that it applies not only to Congress, but to all branches of the federal government, and to all branches of state and local government. It restricts government less in that it provides no protection to some types of speech and only limited protection to others. This report provides an overview of the major exceptions to the First Amendment — of the ways that the Supreme Court has interpreted the guarantee of freedom of speech and press to provide no protection or only limited protection for some types of speech. For example, the Court has decided that the First Amendment provides no protection to obscenity, child pornography, or speech that constitutes “advocacy of the use of force or of law violation ... where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Court has also decided that the First Amendment provides less than full protection to commercial speech, defamation (libel and slander), speech that may be harmful to children, speech broadcast on radio and television, and public employees’ speech. -

Materials on Proposed Changes to Rule 23

Materials on Proposed Changes to Rule 23 Prepared for the First Annual Civil Procedure Workshop July 2015 1 of 234 June 17, 2015 Colleagues, As you know, the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules is presently considering amendments to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Several members of the Advisory Committee will attend a session of the Civil Procedure Workshop on July 17, 2015, to discuss their work with attendees. I have assembled materials on several of these proposed amendments, should any of you wish to prepare for our roundtable discussion with the Advisory Committee members. These materials consist chiefly of Advisory Committee documents, significant U.S. Court of Appeals decisions on the issues that several of the proposed amendments address, and pertinent sections from the American Law Institute’s Principles of the Law of Aggregate Litigation. I have not included any secondary literature, with the exception of a Judicature article by Richard Marcus introducing the Advisory Committee’s agenda. (Prof. Marcus is the committee’s associate reporter.) If you wish to read more than what I have excerpted here, I have compiled a short list of some additional reading below. The included materials and the suggested articles are based on a judgment as to what would be helpful in getting someone up to speed on the Advisory Committee’s deliberations. They are hardly comprehensive, and I harbor no illusion that I have necessarily identified all the key texts. I’m hopeful that they will help get you started. See you in Seattle, Dave Marcus Professor of Law University of Arizona Rogers College of Law Suggested Additional Reading General • Robert H.