Admission to the Bar: a Constitutional Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

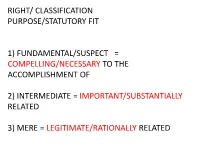

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

Mass Times Reconciliation

2252 Woodruff Rd., Simpsonville, SC 29681 Ph: 864-288-4884 Email: [email protected] Website: smmcc.org Fax: 864-297-5804 Office Hours: Monday—Friday, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. September 29, 2019 – 26th Sunday in Ordinary Time Rev. Theo Trujillo, Pastor Mass Times Monday—Friday 8:30 a.m. and noon Tuesday* - 7 p.m. *Except the 1st Tuesday of the month Saturday 8:30 a.m. Vigil 5 p.m. and 7 p.m. (Spanish) Sunday 7:30 a.m., 9 a.m., 11 a.m., 1 p.m. (Spanish) and 6 p.m. Life Teen Filipino Mass First Saturday at 10 a.m. Polish Mass Last Sunday at 3 p.m. Reconciliation Saturdays after the 8:30 a.m. Mass and 3:30 p.m. - 4:45 p.m. or by appointment Spiritual Life 2 Sacraments 5 Formation 5 Retreats & Conferences 9 Ministries in Action 9 Parish Life 12 Other News 14 In the Community 14 Check us out at www.smmcc.org Page 1 SPIRITUAL LIFE Mass Intentions Today’s Readings Lecturas de hoy Saturday—September 28 Am 6:1a, 4-7; Ps 146:7-10; 1 Tm 6:11-16; Lk 16:19-31 8:30 a.m. Ken Ols † 5 p.m. Nathalie Long † Readings for the Week Lecturas de la semana 7 p.m. St. Mary Magdalene Parish Monday: Zec 8:1-8; Ps 102:16-21, 29, 22-23; Lk 9:46-50 Sunday—September 29 Tuesday: Zec 8:20-23; Ps 87:1b-7; Lk 9:51-56 7:30 a.m. -

D ...1 ...2 N ...3 Gr ...5 Tr ...6 Bg ...7 Ro ...9

Tectron D .....1 I .....2 N .....3 GR .....5 TR .....6 BG .....7 RO .....9 GB .....1 NL .....2 FIN .....4 CZ .....5 SK .....6 EST .....8 CN .....9 F .....1 S .....3 PL .....4 H .....5 SLO .....7 LV .....8 RUS .....9 E .....2 DK .....3 UAE .....4 P .....6 HR .....7 LT .....8 Design & Quality Engineering GROHE Germany 96.852.031/ÄM 221937/01.12 1 2 3 A A C B E A1 D B G F 2 3 A A C A1 E B D F G B III Elektroinstallation D Die Elektroinstallation muss vor der Montage des Anwendungsbereich Rohbauschutzes abgeschlossen sein. Die Elektro- installation (230 V Anschlusskabel in die Anschlussbox) Wandeinbaukasten geeignet für: muss auch vor der Montage des Rohbauschutzes • Netzbetriebene Armatur durchgeführt werden, wenn bei Erstinstallation eine • Batteriebetriebene Armatur mechanische Armatur installiert wird und später auf eine • Manuell betätigte Armatur netzbetriebene Armatur umgerüstet werden soll! Sicherheitsinformationen Transformatorunterteil anschließen! • Die Installation darf nur in frostsicheren Räumen vorgenommen Die Elektroinstallation darf nur von einem Elektro-Fachinstallateur werden. vorgenommen werden! Dabei sind die Vorschriften nach IEC 364-7- • Die Steuerelektronik ist ausschließlich zum Gebrauch in 701-1984 (entspr. VDE 0100 Teil 701) sowie alle nationalen und geschlossenen Räumen geeignet. örtlichen Vorschriften zu beachten! • Nur Originalteile verwenden. • Es darf nur Rundkabel mit 6 bis 8,5mm Außendurchmesser verwendet werden. Technische Daten • Die Spannungsversorgung muss separat schaltbar sein, siehe • Spannungsversorgung 230 V AC Abb. [1]. (Transformator 230 V AC/12 V AC) • Leistungsaufnahme 1,8 VA 1. 230 V-Anschlusskabel (A) in Transformator-Unterteil einführen, siehe • Mindestfließdruck 0,5 bar Abb. -

Sound Bar Barre De Son Barra De Sonido

E:\Works\4746091112\4746091112HTX8500UC2\00COV- masterpage: Left F:\#Sagyou\1102\4746091111\4746091111HT8500UC2\00COV- masterpage: HTX8500UC2\110BCO.fm HTX8500UC2\010COV.fm Right Sound Bar Operating Instructions US Barre de son Manuel d’instructions FR Manual de instrucciones ES Barra de sonido http://www.sony.net/ ©2019 Sony Corporation Printed in Malaysia Imprimé en Malaisie 4-746-091-11(2) HT-X8500 HT-X8500 HT-X8500 4-746-091-11(2) 4-746-091-11(1) Owner’s Record CAUTION The model and serial numbers are Risk of explosion if the battery is located on the bottom of the Sound Bar. replaced by an incorrect type. Record the serial numbers in the space Do not expose batteries or appliances provided below. Refer to them with battery-installed to excessive heat, whenever you call upon your Sony such as sunshine and fire. dealer regarding the Sound Bar. Indoor use only. Model No. HT-X8500 Serial No. For the Sound Bar The nameplate is located on the bottom of the Sound Bar. WARNING For the AC adapter To reduce the risk of fire or electric Labels for AC adapter Model No. and shock, do not expose this Sound Bar Serial No. are located at the bottom of to rain or moisture. AC adapter. For the customers in the U.S.A. The AC adapter is not disconnected from the mains as long as it is Important Safety Instructions connected to the AC outlet, even if the 1) Read these instructions. Sound Bar itself has been turned off. 2) Keep these instructions. To reduce the risk of fire, do not cover 3) Heed all warnings. -

Clinical and Histological Evaluation of Direct Pulp Capping on Human Pulp Tissue Using a Dentin Adhesive System

Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International Volume 2016, Article ID 2591273, 9 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/2591273 Research Article Clinical and Histological Evaluation of Direct Pulp Capping on Human Pulp Tissue Using a Dentin Adhesive System Alicja Nowicka,1 Ryta Aagocka,1 Mariusz Lipski,2 MirosBaw Parafiniuk,3 Katarzyna Grocholewicz,4 Ewa Sobolewska,5 Agnieszka Witek,1 and Jadwiga Buczkowska-RadliNska1 1 Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland 2Department of Preclinical Conservative Dentistry and Preclinical Endodontics, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland 3Department of Forensic Medicine, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland 4Department of General Dentistry, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland 5Department of Gerodontology, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland Correspondence should be addressed to Alicja Nowicka; [email protected] Received 18 May 2016; Revised 10 August 2016; Accepted 1 September 2016 Academic Editor: Hojae Bae Copyright © 2016 Alicja Nowicka et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Objective. This study presents a clinical and histological evaluation of human pulp tissue responses after direct capping using anew dentin adhesive system. Methods. Twenty-eight caries-free third molar teeth scheduled for extraction were evaluated. The pulps of 22 teeth were mechanically exposed and randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups: Single Bond Universal or calcium hydroxide. Another group of 6 teeth acted as the intact control group. The periapical response was assayed, and a clinical examination was performed. The teeth were extracted after 6 weeks, and a histological analysis wasperformed.Thepulpstatuswasassessed,andthethicknessof the dentin bridge was measured and categorized using a histological scoring system. -

Confectionery, Soft Drinks, Crisps & Snacks • Christmas

CUSTOMER NAME ACCOUNT NO. RETAIL PRICE GUIDE & ORDER BOOK October - December 2018 11225 11226 MALTESERS MALTESERS REINDEER MINI REINDEER 29g x 32 59g x 24 £10.79 £18.76 RRP - £0.65 POR 38% RRP - £1.29 POR 27% CONFECTIONERY, SOFT DRINKS, CRISPS & SNACKS • CHRISTMAS 2018 8621 TrueStart Coff ee Vanilla Coconut Cold Brew 8620 TrueStart Coff ee Original Black Cold Brew 8622 TrueStart Coff ee Chilli Chocolate Cold Brew 250ml x 12 £20.49 ZERO-RATED VAT RRP £2.49 - POR 32% ZERO RATED VAT TrueStart Nitro Cold Brew Coff ee Infused with nitrogen for a wildly smooth, refreshing coff ee drink Contents Welcome Contents page I would like to introduce you to my Company. Youings has been supplying tobacco and confectionery for over 125 years, a business Confectionery passed down from father to son through four generations. We therefore have a wealth of experience and knowledge of the trade. The range Countlines 6 has broadened over the years to incorporate crisps, snacks, soft drinks, grocery, wines, beers and spirits, coffee and coffee machines. Bags 20 Being a family run business we believe in giving a first class service. Childrens With regular calls from our sales team every customer is known to us 26 personally and not just a number on a computer screen. Whenever there is a need to contact someone in our company he or she should always Weigh Out, Pick ‘n’ Mix, Jars 31 be able to speak to you. We consider ourselves to be extremely competitive and offer one of the Seasonal most extensive ranges you will find in either delivered wholesale or cash and carry. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

Mestarit Biljardiliigassa Vuosilta 1997 - 2016

MESTARIT BILJARDILIIGASSA VUOSILTA 1997 - 2016 1997 Joukkueliigassa yhdeksän lohkoa, 64 joukkuetta. Pelaajia liigassa 600. Vantaa Mestarijoukkueet Kartanon Kievari, Helsinki Hotelli Vantaa Mestaripelaaja Harri Nurminen, Colorado Bar, Kouvola Lappeenranta Mestarijoukkue Harley Baari, Lappeenranta Hotelli Lappee 1998 Joukkueliigassa 24 lohkoa, 166 joukkuetta. Jyväskylä Mestarijoukkue Harald´s Team, Harald´s Pub, Naantali Free Time Mestaripelaaja Simo Ranta, Barbaari Bar, Oulainen. Naisten mestari Terhi Valtanen, Tony´s Pub, Kuopio. Pelaajia liigassa 1421. 1999 Joukkueliigassa 23 lohkoa, 170 joukkuetta. Lappeenranta Pelaajia liigassa 1520 Hotelli Lappee Mestarijoukkue Story, Old Story, Vantaa. Mestaripelaaja Tony Mikkola, Pub Alabama, Järvenpää. Naisten mestari Tarja Savinainen, Malmikumpu, Outokumpu. 2000 Joukkueliigassa 22 lohkoa, 160 joukkuetta. Kuopio Pelaajia liigassa 1510 Puijonsarvi Mestarijoukkue Dooris Team, Dooris, Nilsiä. Naisjoukkueita neljä, mestari FB:n Namut, Pub Alabama, Järvenpää Mestaripelaaja Tomi Nertamo, Old Story, Vantaa. Naisten mestari Tarja Savinainen, Malmikumpu, Outokumpu. 2001 5 v. Joukkueliigassa 21 lohkoa, 140 joukkuetta. Jyväskylä Pelaajia liigassa 1470 Elohuvi Mestarijoukkue J´s 5 Predators, J´s 5 Cafe, Imatra Naisjoukkueiden mestari Kukko Bar, Kalpea Kukko, Kajaani Mestaripelaaja Mikko Mustonen, Pub Hertas, Vantaa Naisten mestari Tarja Savinainen, Millenium Bar, Joensuu 2002 Joukkueliigassa 22 lohkoa, 140 joukkuetta. Tampere Pelaajia 1378 Hotelli Ilves Mestarijoukkue Ale Royals, Ale Pub, Hyvinkää Naisjoukkueiden mestari Kukko Bar, Kalpea Kukko, Kajaani Mestaripelaaja Tommi Hölsö, Rosso, Vantaa Naisten mestari Tarja Savinainen, Fever Cafe, Joensuu 2003 Joukkueliigassa 22 lohkoa, 147 joukkuetta. Helsinki Pelaajia liigassa 1470 Hotelli Hesperia Mestarijoukkue A.B.C I, Pub Alabama, Järvenpää Naisjoukkueiden mestari Anne´s Angels, Haarikka Pub, Lappeenranta Mestaripelaaja Jussi Iivonen, Pelimanni Pub, Mikkeli Naisten mestari Tarja Savinainen, Beer Stop Pub, Joensuu 2004 Joukkueliigassa 24 lohkoa, 164 joukkuetta. -

Harvard Wins the Varsity and Freshman Races

u i ) U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, June 25. Last 24 Hours' rainfall, .02. SUGAR. 96 Degree Test Centrifugals, 4.25c. Per Ton, JS5.00. Temperature, Max. 80; Min. 72. Weather, fair. 88 Analysis Beets, 10s. ll;d. Per Ton, $36.20. ESTABLISHED JULY 2. 1858. uat VOL. XLVIL, NO. HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, FRIDAY, JUNE 26, 1908. i 8075. PRICE FIVE CENTS. IL I THE ITINERARY MM ,'S INSPECTION OF THE ITINERARY HARVARD WINS tle-- ur-ta-- ne; BOOSTER DINNER' PEARL FOR KAUAI TOUR THE VARSITY AND es. OF THE BIC Secretary Garfield to Spend eet Ninety Were Present and Some Secretary Garfield and Party . Interesting Speechs Were Will See Lochs and Visit Saturday Among the FRESHMAN RACES : FLEET Delivered. Sisal Plant. Barons. alr tat. The Commercial Club gave a "boost- This morning at nine o'clock the Sec- A. Gartley went to Kauai last even- Rebels Capture a Town in Mexico Funeral of er" dinner last evening. It was served retary of the Interior, accompanied by ing to make the final arrangements for at 7 o'clock and about ninety sat down a number of prominent citizens, will Secretary Garfield's tour of the Garden Cleveland to Be Very Simple There Will Latest Orders Posted to it. The menu was an excellent one board the U. S. S. Iroquois for a tour Island. a good incentive to the frame of mind of inspection of Pearl Harbor. The The itinerary as arranged by Mr. Be No Military Escort at the Naval which makes boosting easy and nat- party will sail about the harbor dur- Gartley, George H. -

Our Liturgy Parish Journal

Mon - Zec 8:1-8; Ps 102:16-18, 19-21, 29 and 22-23; Lk 9:46- OUR LITURGY 50 WE KEEP IN OUR PRAYERS Tues- Zec 8:20-23; Ps 87:1b-3, 4-5, 6-7; Lk 9:51-56 Wed - Neh 2:1-8; Ps 137:1-2, 3, 4-5, 6; Mt 18:1-5, 10 Those serving in the Armed Forces: Charles Thurs – Neh 8:1-4a, 5-6, 7b-12; Ps 19:8, 9, 10, 11; Lk 10:1- Misura; Patrick Liam McKerry; Megan Navarro; 12 Fri – Bar 1:15-22; Ps 79:1b-2, 3-5, 8, 9; Lk 10:13-16 Chris Kwatkoski; Luiz Maurina; Colleen Sat – Bar 4:5-12, 27-29; Ps 69:33-35, 36-37; Lk 10:17-24 McEntegart Sun - Hab 1:2-3; 2:2-4; Ps 95:1-2, 6-7, 8-9; 2 Tm 1:6-8, 13- Those who are sick and shut-in: Muriel & Kathy 14; Lk 17:5-10 Matta; Leslie Fagan; Brendan Lynch; Anthony WORSHIP SCHEDULE Castellano; Jessie Grodziak; Edward Connors; Pauline Wittman, and Frances Szala, Cecilia Monday, September 30 D’Agostin, George & Helen Huss, Jeanette 9:00a Evelyn Eckhoff Rogers, Jim & Shirley Prato, Jonathan Fonseca, Tuesday, October 1 Emily Lucas, Mary Anne Grandinetti, Patricia 9:00a Robert Ollwerther Kerod, Rose Tirone, Agnes Gavigan, Maggie Wednesday, October 2 Wright, Donna Schaefer; Anna Kozlowska; 9:00a Michele Scotto di Santolo Kathleen Pinto; Grace Ziadie; John Fossa; Ann Thursday, October 3 Marie Ziadie, Kathy Zoeller, Lavina Gelpi, David 9:00a Stu Paynter Merkel, Helen Fertitta, Corrine & John Kerod, Louis Gelpi, DeMaris Miranda, David Heithmar, Friday, October 4 Josephina Dorn, Anthony DeVito, Marty 9:00a Peter, Paul, and Christian Magnusson Rozensweig, Bob Caruso, Marie Bohacik, Eugene Saturday, October 5 Doyle, Thomas Lorenc, Anna & Juan Rivera, Ken 9:00a Mary Euskie & Natalie, Josephine Babinec, Sister Gloria 4:00p Rev.