BOROUGH of DURYEA V. GUARNIERI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

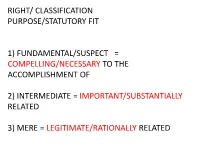

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

Case and ~C®Mment

251 CASE AND ~C®MMENT. CROWN -SERVANT- INCORPORATION -IMMUNITY FROM BEING SUED. The recent case of Gilleghan v. Minister of Healthl decided by Farwell, J., is a decision on the questions : Will an action lie against a Minister-of the Crown in respect of an act admittedly done as a Minister of the Crown? Or -is the true view that the only remedy is against the Crown by petition of right? Does the mere incorporation. of a servant of the Crown confer the privilege of suing and the liability to be sued? The rationale for the general rule that a servant of the Crown cannot be sued in his official capacity is that the servant holds no assets in his official capacity which can be seized in satisfaction of a judgment. He holds only on behalf of the Crown.2 Collins, M.R., in Bainbridge v. Postmaster-General3 said : "The revenue of the country cannot be reached by an action against an official, unless there is some provision to be found in the legisla~ tion to enable this to be done." In the Gilleghan case the defendant moved to-strike out the statement of claim. The Minister of Health was established by the Ministry of Health Act- which provided, inter alia, that the Minister "may sue and be sued in the name of the Minister of Health" and that "for the purpose of acquiring and holding land" the Minister for the time being "shall be a corporation sole." Farwell, J ., decided that the provision that the Minister may sue and be sued does not give the plaintiff a cause of action for breach of contract against the Minister. -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

THE LEGACY of the MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 the Magna Carta Controlled the Power Government Ruled with the Consent of Eventually Spreading Around the Globe

THE LEGACY OF THE MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 The Magna Carta controlled the power government ruled with the consent of eventually spreading around the globe. of the King for the first time in English the people. The Magna Carta was only Reissues of the Magna Carta reminded history. It began the tradition of respect valid for three months before it was people of the rights and freedoms it gave for the law, limits on government annulled, but the tradition it began them. Its inclusion in the statute books power, and a social contract where the has lived on in English law and society, meant every British lawyer studied it. PETITION OF RIGHT 1628 Sir Edward Coke drafted a document King Charles I was not persuaded by By creating the Petition of Right which harked back to the Magna Carta the Petition and continued to abuse Parliament worked together to and aimed to prevent royal interference his power. This led to a civil war, and challenge the King. The English Bill with individual rights and freedoms. the King ultimately lost power, and his of Rights and the Constitution of the Though passed by the Parliament, head! United States were influenced by it. HABEAS CORPUS ACT 1679 The writ of Habeas Corpus gives imprisonment. In 1697 the House of Habeas Corpus is a writ that exists in a person who is imprisoned the Lords passed the Habeas Corpus Act. It many countries with common law opportunity to go before a court now applies to everyone everywhere in legal systems. and challenge the lawfulness of their the United Kingdom. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs

TH AL LAW JORAL JOHN C.P. GOLDBERG The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs A B ST RACT. In our legal system, redressing private wrongs has tended to be the business of tort law, itself traditionally a branch of the common law. But do individuals have a "vested interest" in law that redresses wrongs? If so, do state and federal governments have a constitutional duty to provide that law? Since the New Deal era, conventional wisdom has held that individuals do not possess such a right, and consequently, government bears no such duty. In this view, it is a matter of unfettered legislative discretion- "whim" -whether or how to provide a law of redress. This view is wrongheaded. To be clear: I do not argue that individuals have a property-like interest in a particular corpus of tort rules. The law of tort is always capable of improvement, and legislatures have an obligation and the requisite authority to undertake such improvements. Nonetheless, I do argue that tort law, understood as a law for the redress of private wrongs, forms part of the basic structure of our government. And though the Constitution does not confer on any particular individual a right to a specific version of tort rules, all American citizens have a right to a body of law for the redress of private wrongs that generates meaningful and judicially enforceable limits on tort reform legislation. A UT HO R. John C.P. Goldberg is Associate Dean for Research and Professor, Vanderbilt Law School. -

The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: the Gentile V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 43 1993 The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision Suzanne F. Day Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Suzanne F. Day, The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision, 43 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1347 (1993) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol43/iss4/43 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE SUPREME COURT'S AITACK ON ATTORNEYS' FREEDOM OF ExPRESSION: THE GENTILE v. STATE BAR OF NEVADA DECISION TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............. ............ 1349 A. The Dilemma of the Defense Attorney ....... 1349 B. State Court Rules Restricting Attorney Communication with the Media ............. 1350 11. CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS RAISED BY RESTRICTING PRETRIAL PUBLICITY THROUGH CURBING THE SCOPE OF ATrORNEY SPEECH: THE FAIR TRIAL - FREE PRESS DEBATE ...... ........................ 1351 A. The Sheppard v. Maxwell Decision: The United States Supreme Court's Directive to Trial Court Judges ............................ 1352 B. The Conflicting First Amendment Rights of Attorneys, Sixth Amendment Rights of the Defendant, and the State and Public Interest in the Impartial Administration of Justice ........... 1355 1. What the Amendments Guarantee ......... 1355 2. -

Attorney Solicitation: the Scope of State Regulation After <Em>Primus</Em> and <Em>Ohralik</Em>

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 12 1978 Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik David A. Rabin University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Profession Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Rabin, Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik, 12 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 144 (1978). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol12/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTORNEY SOLICITATION: THE SCOPE OF STATE REGULATION AFTER PRIMUS AND OHRALIK Within the past few years, there has been a growing concern both within and without the legal profession-over increasing the layman's access to legal services. Two of the principal means of increasing this access, advertising and solicitation, 1 have long been prohibited by the organized bar, although a few minor exceptions have been allowed. In lff77, the question of the constitutionality of prohibitions against legal advertising was presented to the United States Supreme Court in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona. 2 The Court ruled in a landmark decision that certain types of advertising could not be prohibited, but expressly reserved the question of the con stitutionality of prohibitions against in-person solicitation.3 Eleven months after Bates, the Court decided two attorney solicitation cases, In re Primus4 and Ohra/ik v. -

The History of the Second Amendment

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 28 Number 3 Spring 1994 pp.1007-1039 Spring 1994 The History of the Second Amendment David E. Vandercoy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David E. Vandercoy, The History of the Second Amendment, 28 Val. U. L. Rev. 1007 (1994). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol28/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Vandercoy: The History of the Second Amendment THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND AMENDMENT DAVID E. VANDERCOY* A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.' I. INTRODUCTION Long overlooked or ignored, the Second Amendment has become the object of some study and much debate. One issue being discussed is whether the Second Amendment recognizes the right of each citizen to keep and bear arms,2 or whether the right belongs solely to state governments and empowers each 3 state to maintain a military force. The debate has resulted in odd political alignments which in turn have caused the Second Amendment to be described recently as the most embarrassing provision of the Bill of Rights.4 Embarrassment results from the politics associated with determining whether the language creates a state's right or an individual right. -

The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause Samuel Wiseman

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 36 | Number 1 Article 5 2009 Discrimination, Coercion, and the Bail Reform Act of 1984: The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause Samuel Wiseman Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Samuel Wiseman, Discrimination, Coercion, and the Bail Reform Act of 1984: The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause, 36 Fordham Urb. L.J. 121 (2009). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol36/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\server05\productn\F\FUJ\36-1\FUJ105.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-JAN-09 13:20 DISCRIMINATION, COERCION, AND THE BAIL REFORM ACT OF 1984: THE LOSS OF THE CORE CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTIONS OF THE EXCESSIVE BAIL CLAUSE Samuel Wiseman* Introduction................................................... 122 R I. A Brief History of the Excessive Bail Clause of the Eighth Amendment ................................... 123 R A. The Petition of Right .............................. 124 R B. The Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 .................. 126 R C. The Excessive Bail Clause of the English Bill of Rights ............................................. 127 R D. Inclusion in the Bill of Rights ..................... 127 R E. Other Bail Provisions in Early America .......... 128 R II. Interpretation of the Excessive Bail Clause Before Salerno ............................................... -

Exceptions to the First Amendment

Order Code 95-815 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Updated July 29, 2004 Henry Cohen Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Summary The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press....” This language restricts government both more and less than it would if it were applied literally. It restricts government more in that it applies not only to Congress, but to all branches of the federal government, and to all branches of state and local government. It restricts government less in that it provides no protection to some types of speech and only limited protection to others. This report provides an overview of the major exceptions to the First Amendment — of the ways that the Supreme Court has interpreted the guarantee of freedom of speech and press to provide no protection or only limited protection for some types of speech. For example, the Court has decided that the First Amendment provides no protection to obscenity, child pornography, or speech that constitutes “advocacy of the use of force or of law violation ... where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Court has also decided that the First Amendment provides less than full protection to commercial speech, defamation (libel and slander), speech that may be harmful to children, speech broadcast on radio and television, and public employees’ speech.