The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause Samuel Wiseman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case and ~C®Mment

251 CASE AND ~C®MMENT. CROWN -SERVANT- INCORPORATION -IMMUNITY FROM BEING SUED. The recent case of Gilleghan v. Minister of Healthl decided by Farwell, J., is a decision on the questions : Will an action lie against a Minister-of the Crown in respect of an act admittedly done as a Minister of the Crown? Or -is the true view that the only remedy is against the Crown by petition of right? Does the mere incorporation. of a servant of the Crown confer the privilege of suing and the liability to be sued? The rationale for the general rule that a servant of the Crown cannot be sued in his official capacity is that the servant holds no assets in his official capacity which can be seized in satisfaction of a judgment. He holds only on behalf of the Crown.2 Collins, M.R., in Bainbridge v. Postmaster-General3 said : "The revenue of the country cannot be reached by an action against an official, unless there is some provision to be found in the legisla~ tion to enable this to be done." In the Gilleghan case the defendant moved to-strike out the statement of claim. The Minister of Health was established by the Ministry of Health Act- which provided, inter alia, that the Minister "may sue and be sued in the name of the Minister of Health" and that "for the purpose of acquiring and holding land" the Minister for the time being "shall be a corporation sole." Farwell, J ., decided that the provision that the Minister may sue and be sued does not give the plaintiff a cause of action for breach of contract against the Minister. -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

THE LEGACY of the MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 the Magna Carta Controlled the Power Government Ruled with the Consent of Eventually Spreading Around the Globe

THE LEGACY OF THE MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 The Magna Carta controlled the power government ruled with the consent of eventually spreading around the globe. of the King for the first time in English the people. The Magna Carta was only Reissues of the Magna Carta reminded history. It began the tradition of respect valid for three months before it was people of the rights and freedoms it gave for the law, limits on government annulled, but the tradition it began them. Its inclusion in the statute books power, and a social contract where the has lived on in English law and society, meant every British lawyer studied it. PETITION OF RIGHT 1628 Sir Edward Coke drafted a document King Charles I was not persuaded by By creating the Petition of Right which harked back to the Magna Carta the Petition and continued to abuse Parliament worked together to and aimed to prevent royal interference his power. This led to a civil war, and challenge the King. The English Bill with individual rights and freedoms. the King ultimately lost power, and his of Rights and the Constitution of the Though passed by the Parliament, head! United States were influenced by it. HABEAS CORPUS ACT 1679 The writ of Habeas Corpus gives imprisonment. In 1697 the House of Habeas Corpus is a writ that exists in a person who is imprisoned the Lords passed the Habeas Corpus Act. It many countries with common law opportunity to go before a court now applies to everyone everywhere in legal systems. and challenge the lawfulness of their the United Kingdom. -

The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs

TH AL LAW JORAL JOHN C.P. GOLDBERG The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs A B ST RACT. In our legal system, redressing private wrongs has tended to be the business of tort law, itself traditionally a branch of the common law. But do individuals have a "vested interest" in law that redresses wrongs? If so, do state and federal governments have a constitutional duty to provide that law? Since the New Deal era, conventional wisdom has held that individuals do not possess such a right, and consequently, government bears no such duty. In this view, it is a matter of unfettered legislative discretion- "whim" -whether or how to provide a law of redress. This view is wrongheaded. To be clear: I do not argue that individuals have a property-like interest in a particular corpus of tort rules. The law of tort is always capable of improvement, and legislatures have an obligation and the requisite authority to undertake such improvements. Nonetheless, I do argue that tort law, understood as a law for the redress of private wrongs, forms part of the basic structure of our government. And though the Constitution does not confer on any particular individual a right to a specific version of tort rules, all American citizens have a right to a body of law for the redress of private wrongs that generates meaningful and judicially enforceable limits on tort reform legislation. A UT HO R. John C.P. Goldberg is Associate Dean for Research and Professor, Vanderbilt Law School. -

The History of the Second Amendment

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 28 Number 3 Spring 1994 pp.1007-1039 Spring 1994 The History of the Second Amendment David E. Vandercoy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David E. Vandercoy, The History of the Second Amendment, 28 Val. U. L. Rev. 1007 (1994). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol28/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Vandercoy: The History of the Second Amendment THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND AMENDMENT DAVID E. VANDERCOY* A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.' I. INTRODUCTION Long overlooked or ignored, the Second Amendment has become the object of some study and much debate. One issue being discussed is whether the Second Amendment recognizes the right of each citizen to keep and bear arms,2 or whether the right belongs solely to state governments and empowers each 3 state to maintain a military force. The debate has resulted in odd political alignments which in turn have caused the Second Amendment to be described recently as the most embarrassing provision of the Bill of Rights.4 Embarrassment results from the politics associated with determining whether the language creates a state's right or an individual right. -

521 N.W.2D 632 (N.D

|N.D. Supreme Court| Bulman v. Hulstrand Const., 521 N.W.2d 632 (N.D. 1994) Filed Sep. 13, 1994 [Go to Documents] [Concurrence and Dissent filed.] IN THE SUPREME COURT STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA Judy Ann Bulman, Plaintiff and Appellant v. Hulstrand Construction Co., Inc.; and the State of North Dakota, Defendants and Appellees and Otto Moe and Robert Heim, individually and as partners doing business as Custom Tool & Repair Service, a/k/a CT & RS, and Custom Tool & Repair Service (CT & RS), Defendants Civil No. 940047 Appeal from the District Court for Slope County, Southwest Judicial District, the Honorable Donald L. Jorgensen, Judge. AFFIRMED IN PART, REVERSED IN PART, AND REMANDED. Opinion of the Court by Levine, Justice. J. P. Dosland (argued), of Dosland, Nordhougen, Lillehaug, Johnson & Saande, P.O. Box 100, Moorhead, MN 56560, for plaintiff and appellant. Steven A. Storslee (argued), of Fleck, Mather & Strutz, P.O. Box 2798, Bismarck, ND 58502-2798, for defendant and appellee Hulstrand Construction Company. Laurie J. Loveland (argued), Solicitor General, Attorney General's Office, 900 East Boulevard Avenue, Bismarck, ND 58505-0041, for defendant and appellee State of North Dakota. Jeffrey White, Associate General Counsel, Association of Trial Lawyers of America, 1050 31st Street NW, Washington, DC 20007, and David R. Bossart, of Conmy, Feste, Bossart, Hubbard & Corwin, Ltd., 400 Norwest Center, Fargo, ND 58126, for amicus curiae Association of Trial Lawyers of America. Brief filed. [521 N.W.2d 633] Bulman v. Hulstrand Construction Co. Civil No. 940047 Levine, Justice. Judy Ann Bulman appeals from a summary judgment dismissing her wrongful death action against Hulstrand Construction Company and the State of North Dakota. -

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman In 1215, Genghis Khan conquered Beijing on the way to creating the Mongol Empire. The 23rd of September 2015 was the 800th anniversary of the birth of his grandson, Kublai Khan, under whose imperial rule, as the founder of the Yuan dynasty, the extent of the China we know today was determined. 1215 was a big year for executive power. This 800th anniversary of Magna Carta should be approached with a degree of humility. Underlying themes In two earlier addresses during this year’s caravanserai of celebration,1 I have set out certain themes, each recognisably of constitutional significance, which underlie Magna Carta. In this address I wish to focus on four of those themes, as they developed over subsequent centuries, and to do so with a focus on the executive authority of the monarchy. The themes are: First, the king is subject to the law and also subject to custom which was, during that very period, in the process of being hardened into law. Secondly, the king is obliged to consult the political nation on important issues. Thirdly, the acts of the king are not simply personal acts. The king’s acts have an official character and, accordingly, are to be exercised in accordance with certain processes, and within certain constraints. Fourthly, the king must provide a judicial system for the administration of justice and all free men are entitled to due process of law. In my opinion, the long-term significance of Magna Carta does not lie in its status as a sacred text—almost all of which gradually became irrelevant. -

BOROUGH of DURYEA V. GUARNIERI

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2010 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BOROUGH OF DURYEA, PENNSYLVANIA, ET AL. v. GUARNIERI CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT No. 09–1476. Argued March 22, 2011—Decided June 20, 2011 After petitioner borough fired respondent Guarnieri as its police chief, he filed a union grievance that led to his reinstatement. When the borough council later issued directives instructing Guarnieri how to perform his duties, he filed a second grievance, and an arbitrator or- dered that some of the directives be modified or withdrawn. Guarni- eri then filed this suit under 42 U. S. C. §1983, alleging that the di- rectives were issued in retaliation for the filing of his first grievance, thereby violating his First Amendment “right . to petition the Gov- ernment for a redress of grievances”; he later amended his complaint to allege that the council also violated the Petition Clause by denying his request for overtime pay in retaliation for his having filed the §1983 suit. The District Court instructed the jury, inter alia, that the suit and the grievances were constitutionally protected activity, and the jury found for Guarnieri. -

Magna Carta & Parliament

Houses of Parliament Parliamentary Archives Houses of Parliament Parliamentary Archives Magna Carta & Parliament David Carpenter David Prior Professor of Medieval History, Head of Public Services and Outreach, King’s College London Parliamentary Archives Magna Carta & Parliament David Carpenter David Prior Professor of Medieval History, Head of Public Services and Outreach, King’s College London Parliamentary Archives © Parliamentary Copyright House of Lords 2015 FOREWORD INTRODUCTION This guide serves as an engrossments of Magna accompaniment to the Carta greatly enhances the exhibition Magna Carta & opportunity to consider Magna The Speaker The Lord Speaker Parliament which will be on Carta in a parliamentary The Speaker display in the Royal Gallery context and to examine its and Queen’s Robing Room impact on the history of in the House of Lords during Parliament. The House of From The Speaker The granting of Magna Carta by King John at Runnymede February 2015. Elements of the Lords is grateful to the British of the House of on 15 June 1215 is one of the best known events in our exhibition will then travel to Library, Lincoln Cathedral and Commons and history and one which has echoed across eight centuries. various venues during 2015 as Salisbury Cathedral for their The Lord Speaker It has shaped the way we live our lives today. part of the De Montfort project generosity in agreeing to the In a year which also sees the 750th anniversary of the which is being run by the loan of these documents. parliament assembled by Simon de Montfort at Westminster, Parliamentary Archives. This exhibition has been made it is entirely appropriate that this exhibition should seek The exhibition marks the 800th possible by the provision to trace the impact of Magna Carta on the evolution of anniversary of the sealing of of insurance through the Parliament and thereby provide the opportunity to display Magna Carta at Runnymede Government Indemnity some of Parliament’s most iconic documents, such as the in 1215. -

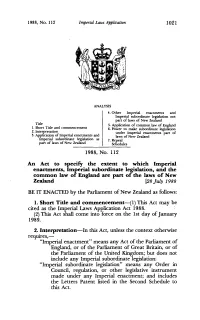

1988 No 112 Imperial Laws Application

1988, No. 112 Imperial Laws Application 1021 ANALYSIS 4. Other Imperial enactments and Imperial subordinate legislation not part of laws of New Zealand Title 5. Application of common law of England 1. Short Title and commencement 6. Power to make subordinate legislation 2. InteTretation under Imperial enactments part of 3. Application of Imperial enactments and laws of New Zealand Imperial subordinate legislation as 7. Repeal part of laws of New Zealand Scliedules 1988, No. 112 An Act to specify the extent to which Imperial enactments, Imperial subordinate legislation, and the common law of England are part of the laws of New Zealand [28 July 1988 BE IT ENACTED by the Parliament of New Zealand as follows: I. Short Tide and commencement-(1) This Act may be cited as the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988. : (2) This Act shall come into force on the 1st day of January 1989. 2. Interpretation-In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,- "Imperial enactment" means any Act of the Parliament of England, or of the Parliament of Great Britain, or of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; but does not include any Imperial subordinate legislation: "Imperial subordinate legislation" means any Order in Council, regulation, or other legislative instrument made under any Imperial enactment; and includes the Letters Patent listed in the Second Schedule to this Act. 1022 Imperial Laws Application 1988, No. 112 8. Application of Imperial enactrnents and Imperial subordinate legislation as part of laws of New Zealand- (1) The Imperial enactments listed in the First Schedule to this Act, and the Imperial subordinate legislation listed in the Second Schedule to this Act, are hereby declared to be part of the laws of New Zealand. -

Fundamental Rights

Review of the Balance of Competences between the United Kingdom and the European Union Fundamental Rights Summer 2014 Review of the Balance of Competences between the United Kingdom and the European Union Fundamental Rights © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This document is also available from our website gcn.civilservice.gov.uk/ Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Fundamental Rights in Context 11 Chapter 2: Development of Competence 19 Chapter 3: The Current State of Competence 25 Chapter 4: Impact on the National Interest 45 Chapter 5: Future Options and Challenges 65 Annex A: Submissions Received to the Call for Evidence 75 Annex B: Engagement Events 79 Annex C: Other Sources Used for the Review 81 Annex D: Glossary of Abbreviations and Acronyms 91 Executive Summary This report examines the balance of competences between the European Union and the United Kingdom in the area of fundamental rights, and is led by the Ministry of Justice (MOJ). Fundamental rights are EU protections that in other contexts are often referred to as human rights, although fundamental rights do not always afford the same guarantees as human rights in other contexts. -

Historical Chronology of Important Constitutional Events

Historical Chronology of Important Constitutional Events A GUIDE TO THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE CANADIAN CONSTITUTION I 2 I 5 Magna Carta (This is the date generally associated with Magna Carta. However, after King John's death and the ensuing period of conflict among the power elite in England, the Charter was re-issued by Henry III in 1225, and later confirmed by Edward I in 1297.) 1628 Charles I accepts the Petition of Right 1663 Royal Government in New France 1670 Royal Charter incorporating the Hudson's Bay Company 1679 Habeas Corpus Act (An Act for the better securing of the Liberty of the Subject, and for the Prevent1on of Imprisonment beyond the Seas) 1689 English Bill of Rights 1701 Act of Settlement 1713 Treaty of Utrecht 1763 The Royal Proclamation 1774 The Quebec Act 1787 (Adoption of the Constitution of the United States of America, 11 years after the Declara- tion of Independence) 1791 The Constitutional Act of 1791 1839 Lord Durham's Report on the Affairs of British North America 1840 The Act of Union 1864 The Quebec Conference 1865 The Colonial Laws Validity Act 1866 The London Conference liv / Chronology 1867 The British North America Act 1870 Order In Council admitting Rupert's Land and the Northwest Territories to the union 1870 The Manitoba Act (Canada) 1871 Order in Council admitting the colony of British Columbia to the union 1873 Order in Council admitting the colony of Prince Edward Island to the union 1875 The Supreme and Exchequer Court Act (Canada) 1880 Order in Council annexing to Canada all British territories and adjacent islands in North America 1896 A.-G.