Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case and ~C®Mment

251 CASE AND ~C®MMENT. CROWN -SERVANT- INCORPORATION -IMMUNITY FROM BEING SUED. The recent case of Gilleghan v. Minister of Healthl decided by Farwell, J., is a decision on the questions : Will an action lie against a Minister-of the Crown in respect of an act admittedly done as a Minister of the Crown? Or -is the true view that the only remedy is against the Crown by petition of right? Does the mere incorporation. of a servant of the Crown confer the privilege of suing and the liability to be sued? The rationale for the general rule that a servant of the Crown cannot be sued in his official capacity is that the servant holds no assets in his official capacity which can be seized in satisfaction of a judgment. He holds only on behalf of the Crown.2 Collins, M.R., in Bainbridge v. Postmaster-General3 said : "The revenue of the country cannot be reached by an action against an official, unless there is some provision to be found in the legisla~ tion to enable this to be done." In the Gilleghan case the defendant moved to-strike out the statement of claim. The Minister of Health was established by the Ministry of Health Act- which provided, inter alia, that the Minister "may sue and be sued in the name of the Minister of Health" and that "for the purpose of acquiring and holding land" the Minister for the time being "shall be a corporation sole." Farwell, J ., decided that the provision that the Minister may sue and be sued does not give the plaintiff a cause of action for breach of contract against the Minister. -

THE LEGACY of the MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 the Magna Carta Controlled the Power Government Ruled with the Consent of Eventually Spreading Around the Globe

THE LEGACY OF THE MAGNA CARTA MAGNA CARTA 1215 The Magna Carta controlled the power government ruled with the consent of eventually spreading around the globe. of the King for the first time in English the people. The Magna Carta was only Reissues of the Magna Carta reminded history. It began the tradition of respect valid for three months before it was people of the rights and freedoms it gave for the law, limits on government annulled, but the tradition it began them. Its inclusion in the statute books power, and a social contract where the has lived on in English law and society, meant every British lawyer studied it. PETITION OF RIGHT 1628 Sir Edward Coke drafted a document King Charles I was not persuaded by By creating the Petition of Right which harked back to the Magna Carta the Petition and continued to abuse Parliament worked together to and aimed to prevent royal interference his power. This led to a civil war, and challenge the King. The English Bill with individual rights and freedoms. the King ultimately lost power, and his of Rights and the Constitution of the Though passed by the Parliament, head! United States were influenced by it. HABEAS CORPUS ACT 1679 The writ of Habeas Corpus gives imprisonment. In 1697 the House of Habeas Corpus is a writ that exists in a person who is imprisoned the Lords passed the Habeas Corpus Act. It many countries with common law opportunity to go before a court now applies to everyone everywhere in legal systems. and challenge the lawfulness of their the United Kingdom. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs

TH AL LAW JORAL JOHN C.P. GOLDBERG The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs A B ST RACT. In our legal system, redressing private wrongs has tended to be the business of tort law, itself traditionally a branch of the common law. But do individuals have a "vested interest" in law that redresses wrongs? If so, do state and federal governments have a constitutional duty to provide that law? Since the New Deal era, conventional wisdom has held that individuals do not possess such a right, and consequently, government bears no such duty. In this view, it is a matter of unfettered legislative discretion- "whim" -whether or how to provide a law of redress. This view is wrongheaded. To be clear: I do not argue that individuals have a property-like interest in a particular corpus of tort rules. The law of tort is always capable of improvement, and legislatures have an obligation and the requisite authority to undertake such improvements. Nonetheless, I do argue that tort law, understood as a law for the redress of private wrongs, forms part of the basic structure of our government. And though the Constitution does not confer on any particular individual a right to a specific version of tort rules, all American citizens have a right to a body of law for the redress of private wrongs that generates meaningful and judicially enforceable limits on tort reform legislation. A UT HO R. John C.P. Goldberg is Associate Dean for Research and Professor, Vanderbilt Law School. -

The History of the Second Amendment

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 28 Number 3 Spring 1994 pp.1007-1039 Spring 1994 The History of the Second Amendment David E. Vandercoy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David E. Vandercoy, The History of the Second Amendment, 28 Val. U. L. Rev. 1007 (1994). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol28/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Vandercoy: The History of the Second Amendment THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND AMENDMENT DAVID E. VANDERCOY* A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.' I. INTRODUCTION Long overlooked or ignored, the Second Amendment has become the object of some study and much debate. One issue being discussed is whether the Second Amendment recognizes the right of each citizen to keep and bear arms,2 or whether the right belongs solely to state governments and empowers each 3 state to maintain a military force. The debate has resulted in odd political alignments which in turn have caused the Second Amendment to be described recently as the most embarrassing provision of the Bill of Rights.4 Embarrassment results from the politics associated with determining whether the language creates a state's right or an individual right. -

The American Experiment

The American2 Experiment Assignment government, where majority desires have an even greater impact on the government. This lesson is based on information in the following Although these ideas are associated with the devel- text selections and video. Carefully read and review opment of the U.S. Constitution, they have their roots all of the materials before taking the practice test. in the preceding colonial and revolutionary experi- The key terms, focus points, and practice test are in- ences in America. The colonists’ English heritage had tended to help ensure mastery of the essential politi- stressed the ideas of both limited government and cal issues surrounding the background and creation self-government. To a large extent, the American rev- of the U.S. Constitution. olutionaries were seeking to retain what they had tra- ditionally understood to be their rights as Text: Chapter 2, “Constitutional Democracy: Pro- Englishmen. Controversy between the American col- moting Liberty and Self-Government,” pp. onists and the English developed in the aftermath of 37–48 the French and Indian War, when the British govern- ment sought to impose several new taxes in order to Declaration of Independence, Appendix A raise revenue. The British first enacted the Stamp Act, then the Townshend Act, and then a tax on tea. Video: “The American Experiment” Because they had no representatives in the English Parliament, the colonists were convinced that these taxes violated the principle of “no taxation without Overview representation,” a right recognized by Englishmen. The colonists met together to articulate their griev- Events like the Watergate break-in during the Nixon ances against the British crown at the First Continen- Administration demonstrate that Americans still tal Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. -

The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause Samuel Wiseman

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 36 | Number 1 Article 5 2009 Discrimination, Coercion, and the Bail Reform Act of 1984: The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause Samuel Wiseman Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Samuel Wiseman, Discrimination, Coercion, and the Bail Reform Act of 1984: The Loss of the Core Constitutional Protections of the Excessive Bail Clause, 36 Fordham Urb. L.J. 121 (2009). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol36/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\server05\productn\F\FUJ\36-1\FUJ105.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-JAN-09 13:20 DISCRIMINATION, COERCION, AND THE BAIL REFORM ACT OF 1984: THE LOSS OF THE CORE CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTIONS OF THE EXCESSIVE BAIL CLAUSE Samuel Wiseman* Introduction................................................... 122 R I. A Brief History of the Excessive Bail Clause of the Eighth Amendment ................................... 123 R A. The Petition of Right .............................. 124 R B. The Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 .................. 126 R C. The Excessive Bail Clause of the English Bill of Rights ............................................. 127 R D. Inclusion in the Bill of Rights ..................... 127 R E. Other Bail Provisions in Early America .......... 128 R II. Interpretation of the Excessive Bail Clause Before Salerno ............................................... -

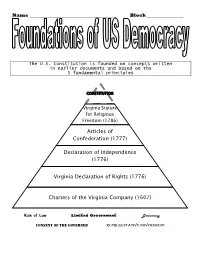

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3. -

The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness Carli N

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 7 | Issue 2 2015 The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness Carli N. Conklin Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, Political Theory Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Carli N. Conklin, The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness, 7 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 195 (2015). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol7/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS CARLI N. CONKLIN ABSTRACT Scholars have long struggled to define the meaning of the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence. The most common understandings suggest either that the phrase is a direct substitution for John Locke’s conception of property or that the phrase is a rhetorical flourish that conveys no substantive meaning. Yet, property and the pursuit of happiness were listed as distinct—not synonymous— rights in eighteenth-century writings. Furthermore, the very inclusion of “the pursuit of happiness” as one of only three unalienable rights enumerated in the Declaration suggests that the drafters must have meant something substantive when they included the phrase in the text. -

American Ideas About the Rights of Man and How a Government Should Operate

American Ideas About the Rights of Man and How A Government Should Operate The Framers of the Constitution were inspired by the following documents and people. Magna Carta (1215) In early 1200’s King John of England began to treat his nobles in ways they felt were unfair. He taxed without asking permission, and put them in jail and took their property without a trial if they refused to pay the taxes. Magna Carta (1215) Many of the Nobles banded together to resist the king’s efforts to take away rights they thought were theirs. They met the king in a place called Runnymeade and forced him to sign a document called the Magna Carta or Great Charter. Magna Carta (1215) The Magna Carta put in writing ideas that are important to our ideas of democracy and rights. 1. Laws that even Kings have to obey. 2. No taxation except by legal means. 3. Right to a fair trial. Mayflower Compact (1620) When the Puritans left England to come to America to escape religious persecution, they were blown off course and landed in Massachusetts, which was outside a colony where there was government. They signed an agreement to establish a government and abide by the laws they made. Mayflower Compact (1630) The Mayflower Compact established these ideas: 1. Established self government and majority rule. 2. A King is not necessary to have laws. 3. Laws can be made by the people for the good of the colony. English Bill of Rights (1689) King James II dismissed parliament and tried to restrict the rights of people in England. -

521 N.W.2D 632 (N.D

|N.D. Supreme Court| Bulman v. Hulstrand Const., 521 N.W.2d 632 (N.D. 1994) Filed Sep. 13, 1994 [Go to Documents] [Concurrence and Dissent filed.] IN THE SUPREME COURT STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA Judy Ann Bulman, Plaintiff and Appellant v. Hulstrand Construction Co., Inc.; and the State of North Dakota, Defendants and Appellees and Otto Moe and Robert Heim, individually and as partners doing business as Custom Tool & Repair Service, a/k/a CT & RS, and Custom Tool & Repair Service (CT & RS), Defendants Civil No. 940047 Appeal from the District Court for Slope County, Southwest Judicial District, the Honorable Donald L. Jorgensen, Judge. AFFIRMED IN PART, REVERSED IN PART, AND REMANDED. Opinion of the Court by Levine, Justice. J. P. Dosland (argued), of Dosland, Nordhougen, Lillehaug, Johnson & Saande, P.O. Box 100, Moorhead, MN 56560, for plaintiff and appellant. Steven A. Storslee (argued), of Fleck, Mather & Strutz, P.O. Box 2798, Bismarck, ND 58502-2798, for defendant and appellee Hulstrand Construction Company. Laurie J. Loveland (argued), Solicitor General, Attorney General's Office, 900 East Boulevard Avenue, Bismarck, ND 58505-0041, for defendant and appellee State of North Dakota. Jeffrey White, Associate General Counsel, Association of Trial Lawyers of America, 1050 31st Street NW, Washington, DC 20007, and David R. Bossart, of Conmy, Feste, Bossart, Hubbard & Corwin, Ltd., 400 Norwest Center, Fargo, ND 58126, for amicus curiae Association of Trial Lawyers of America. Brief filed. [521 N.W.2d 633] Bulman v. Hulstrand Construction Co. Civil No. 940047 Levine, Justice. Judy Ann Bulman appeals from a summary judgment dismissing her wrongful death action against Hulstrand Construction Company and the State of North Dakota. -

The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, 37 Case W

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 37 | Issue 4 1987 The rP ivileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV David S. Bogen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David S. Bogen, The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, 37 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 794 (1987) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol37/iss4/8 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES CLAUSE OF ARTICLE IV David S. Bogen* The Privileges and Immunities Clause ofArticle IV is deeply rooted in the histori- cal context of English law. It developed from colonial charter provisions and the position of the colonists as subjects of a common king, evolved as the colonies ex- panded, survived the Revolutionary War in the Articles of Confederation and was eventually adopted in the Constitution. This Article traces the history of the Privileges and Immunities Clause in order to elaborate on the originalintent embodied in its language. ProfessorBogen states that the clause did not embody natural law concepts, but was solely concerned with creating a national citizenship. He contends thatfear of a naturallaw interpretationhas incorrectlyprevented the Courtfrom finding the clause applicable to citizens in the state where they reside. He suggests that a full examina- tion of the historical origin of the clause could lead to a more concrete basis for judicial interpretation.