The American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yorktown Victory Center Replacement Will Be Named 'American Revolution Museum at Yorktown'

DISPATCH A Newsletter of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation • Spring 2012 Yorktown Victory Center Replacement Will Be Named ‘American Revolution Museum at Yorktown’ Along with a physical transforma- bonds, is estimated at $46 tion of the Yorktown Victory Center will million. Private donations come a new name – “American Revolu- to the Jamestown-Yorktown tion Museum at Yorktown” – adopted Foundation, Inc., will sup- May 10 by the Jamestown-Yorktown port elements of gallery Foundation Board of Trustees and and outdoor exhibits and endorsed by the Jamestown-Yorktown educational resources. Foundation, Inc., Board of Directors. “The new name high- Recommended by a board naming lights the core offering of study task force, the new name will the museum, American be implemented upon completion of Revolution history,” said the museum replacement, and in the Frank B. Atkinson, who meantime the Yorktown Victory Center chaired the naming study will continue in operation as a museum task force comprised of 11 The distinctive two-story main entrance of the American of the American Revolution. members of the Jamestown- Revolution Museum at Yorktown will serve as a focal point Construction is expected to start Yorktown Foundation for arriving visitors. in the second half of 2012 on the proj- and Jamestown-Yorktown name were identified, and research ect, which includes an 80,000-square- Foundation, Inc., boards, “and the in- was undertaken on names currently in foot structure that will encompass ex- clusion of the word ‘Yorktown’ provides use. Selected names were tested with panded exhibition galleries, classrooms a geographical anchor. We arrived Yorktown Victory Center visitors and and support functions, and reorganiza- at this choice through a methodical reviewed by a trademark attorney and tion of the 22-acre site. -

Unit 2 Guide

AP US History Unit 2 Study Guide “Salutary Neglect” Enlightenment terms to remember Balance of trade Philosophes Mercantilism John Locke Tariffs Tabula rasa Navigation Acts Social Contract Natural Rights Montesquieu Benjamin Franklin French and Indian War Ft. Duquesne Relative advantages (Brit./France) Gov. Dinwiddie The Great Expulsion (1755-63) George Washington William Pitt, Sr. The Brave Old Hendrick Battle of the Plains of Abraham Albany Plan for Union Treaty of Paris, 1763 Pontiac´s Rebellion Discontent Proclamation Line of 1763 John Dickinson Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer East Florida, West Florida, Quebec Boston Massacre Sugar Act (1764) Samuel Adams Admiralty courts John Adams Virtual representation Gaspee incident (1772) Stamp Act (1765) Committees of Correspondence Stamp Act Congress Tea Act of 1773 Patrick Henry British East India Co. "Sons of Liberty" Boston Tea Party Quartering Act Quebec Act, 1774 Declaratory Act Coercive (Intolerable) Acts Townshend Duties (1767) First Continental Congress Massachusetts General Court’s Circular Letter (1768) War of Independence Lexington and Concord Battle of Saratoga Second Continental Congress Alliance of 1778 General Washington Netherlands and Spain Olive Branch Petition Valley Forge Battle of Bunker Hill Privateers and the “Law of the Sea” Three-phases of the war League of Armed Neutrality, 1780 Thomas Paine’s Common Sense John Paul Jones Declaration of Independence Yorktown Thomas Jefferson Newburgh Conspiracy Loyalists Sir George Rodney, Battle of Saints, 1782 Hudson Valley Campaign -

Causes of the American Revolution

CAUSES OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION Copyright © 2017 Edmentum - All rights reserved. Generation Date: 10/12/2017 Generated By: Doug Frierson 1. What was the name of the treaty signed in 1763 which officially ended the French and Indian War? A. Treaty of Ghent B. Treaty of Niagara C. Treaty of Paris D. Treaty of Versailles 2. Which of the following was the main reason that American colonists opposed the Stamp Act of 1765? A. The act was taxation without representation. B. The tax was not imposed on the wealthy. C. The act was passed by the king, not Parliament. D. The tax was a large amount of money. 3. The Proclamation of 1763 was established to prevent any settlers from moving _______ of the Appalachian Mountains. A. north B. east C. west D. south 4. The First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774. In an attempt to get the best representation of a united colony, how did the Congress allocate votes between the colonies? A. The number of votes for each colony was based on its population. B. The Congress had no authority; therefore, there were no votes necessary. C. Each of the 13 colonies got one vote. D. Each of the colonies got two votes. 5. The Proclamation of 1763 was established following which of these wars? A. War of 1812 B. Spanish-American War C. Revolutionary War D. French and Indian War 6. Which American colonist was the lawyer who defended the soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre? A. James Madison B. George Washington C. -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

Chapter 5 – the Enlightenment and the American Revolution I. Philosophy in the Age of Reason (5-1) A

Chapter 5 – The Enlightenment and the American Revolution I. Philosophy in the Age of Reason (5-1) A. Scientific Revolution Sparks the Enlightenment 1. Natural Law: Rules or discoveries made by reason B. Hobbes and Lock Have Conflicting Views 1. Hobbes Believes in Powerful Government a. Thomas Hobbes distrusts humans (cruel-greedy-selfish) and favors strong government to keep order b. Promotes social contract—gaining order by giving up freedoms to government c. Outlined his ideas in his work called Leviathan (1651) 2. Locke Advocates Natural Rights a. Philosopher John Locke believed people were good and had natural rights—right to life, liberty, and property b. In his Two Treatises of Government, Lock argued that government’s obligation is to protect people’s natural rights and not take advantage of their position in power C. The Philosophes 1. Philosophes: enlightenment thinkers that believed that the use of reason could lead to reforms of government, law, and society 2. Montesquieu Advances the Idea of Separation of Powers a. Montesquieu—had sharp criticism of absolute monarchy and admired Britain for dividing the government into three branches b. The Spirit of the Laws—outlined his belief in the separation of powers (legislative, executive, and judicial branches) to check each other to stop one branch from gaining too much power 3. Voltaire Defends Freedom of Thought a. Voltaire—most famous of the philosophe who published many works arguing for tolerance and reason—believed in the freedom of religions and speech b. He spoke out against the French government and Catholic Church— makes powerful enemies and is imprisoned twice for his views 4. -

The Stamp Act and Methods of Protest

Page 33 Chapter 8 The Stamp Act and Methods of Protest espite the many arguments made against it, the Stamp Act was passed and scheduled to be enforced on November 1, 1765. The colonists found ever more vigorous and violent ways to D protest the Act. In Virginia, a tall backwoods lawyer, Patrick Henry, made a fiery speech and pushed five resolutions through the Virginia Assembly. In Boston, an angry mob inspired by Sam Adams and the Sons of Liberty destroyed property belonging to a man rumored to be a Stamp agent and to Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson. In New York, delegates from nine colonies, sitting as the Stamp Act Congress, petitioned the King and Parliament for repeal. In Philadelphia, New York, and other seaport towns, merchants pledged not to buy or sell British goods until the hated stamp tax was repealed. This storm of resistance and protest eventually had the desired effect. Stamp sgents hastily resigned their Commissions and not a single stamp was ever sold in the colonies. Meanwhile, British merchants petitioned Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. In 1766, the law was repealed but replaced with the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had the right to make laws binding on the colonies "in all cases whatsoever." The methods used to protest the Stamp Act raised issues concerning the use of illegal and violent protest, which are considered in this chapter. May: Patrick Henry and the Virginia Resolutions Patrick Henry had been a member of Virginia's House of Burgess (Assembly) for exactly nine days as the May session was drawing to a close. -

The Causes of the American Revolution

Page 50 Chapter 12 By What Right Thomas Hobbes John Locke n their struggle for freedom, the colonists raised some age-old questions: By what right does government rule? When may men break the law? I "Obedience to government," a Tory minister told his congregation, "is every man's duty." But the Reverend Jonathan Boucher was forced to preach his sermon with loaded pistols lying across his pulpit, and he fled to England in September 1775. Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that when people are governed "under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such a Government." Both Boucher and Jefferson spoke to the question of whether citizens owe obedience to government. In an age when kings held near absolute power, people were told that their kings ruled by divine right. Disobedience to the king was therefore disobedience to God. During the seventeenth century, however, the English beheaded one King (King Charles I in 1649) and drove another (King James II in 1688) out of England. Philosophers quickly developed theories of government other than the divine right of kings to justify these actions. In order to understand the sources of society's authority, philosophers tried to imagine what people were like before they were restrained by government, rules, or law. This theoretical condition was called the state of nature. In his portrait of the natural state, Jonathan Boucher adopted the opinions of a well- known English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes believed that humankind was basically evil and that the state of nature was therefore one of perpetual war and conflict. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

Civil War and Revolution

SungraphoThema VELS levels 1-3 Civil War and Revolution What can the study of civil war bring to our understanding of revolutions? Professor David Armitage, Harvard University The study of civil war has recently become academic Civil war has gradually become the most widespread, big business, especially among political scientists the most destructive, and now the most characteristic and economists. A surge of intellectual interest in form of organised human violence. Since 1820, an a major problem like this often has two sources: average of two to four per cent of all countries have the internal dynamics of academic disciplines experienced civil war at any given moment. This themselves, and external currents in the wider world striking average disguises the fact that some periods that scholars hope their findings might shape. The were even more acutely afflicted by internal warfare: ongoing ‘boom in the study of civil war,’ as it has for example, the middle decades of the nineteenth been called, has both these motives. Economists who century, the period of the US Civil War, the Taiping study underdevelopment, especially in Africa, have Rebellion and the Indian Mutiny, among other internal isolated civil war as one of its main causes. Students conflicts.2 The decades since 1975 have seen a similar of international relations who focused their attention spike in the incidence of internal warfare. Indeed, in on wars between states have turned to the study of the last thirty years, an average of at least ten per cent civil wars as they found their traditional subject of all countries at any one time have been suffering disappearing before their very eyes: since World War civil war: in 2006 (the last year for which complete II, the developed world has enjoyed a ‘Long Peace’ data are available), there were thirty-two civil wars in without interstate war, while between 1989 and 2006, progress around the world. -

From the American Revolution Through the American Civil War"

History 216-01: "From the American Revolution through the American Civil War" J.P. Whittenburg Fall 2009 Email: [email protected] Office: Young House (205 Griffin Avenue) Web Page: http://faculty.wm.edu/jpwhit Telephone: 757-221-7654 Office Hours: By Appointment Clearly, this isn't your typical class. For one thing, we meet all day on Fridays. For another, we will spend most of our class time "on-site" at museums, battlefields, or historic buildings. This class will concentrate on the period from the end of the American Revolution through the end of the American Civil War, but it is not at all a narrative that follows a neat timeline. I’ll make no attempt to touch on every important theme and we’ll depart from the chronological approach whenever targets of opportunities present themselves. I'll begin most classes with some sort of short background session—a clip from a movie, oral reports, or maybe something from the Internet. As soon as possible, though, we'll be into a van and on the road. Now, travel time can be tricky and I do hate to rush students when we are on-site. I'll shoot for getting people back in time for a reasonably early dinner—say 5:00. BUT there will be times when we'll get back later than that. There will also be one OPTIONAL overnight trip—to the Harper’s Ferry and the Civil War battlefields at Antietam and Gettysburg. If these admitted eccentricities are deeply troubling, I'd recommend dropping the course. No harm, no foul—and no hard feelings. -

The American Experiment

The American2 Experiment Assignment government, where majority desires have an even greater impact on the government. This lesson is based on information in the following Although these ideas are associated with the devel- text selections and video. Carefully read and review opment of the U.S. Constitution, they have their roots all of the materials before taking the practice test. in the preceding colonial and revolutionary experi- The key terms, focus points, and practice test are in- ences in America. The colonists’ English heritage had tended to help ensure mastery of the essential politi- stressed the ideas of both limited government and cal issues surrounding the background and creation self-government. To a large extent, the American rev- of the U.S. Constitution. olutionaries were seeking to retain what they had tra- ditionally understood to be their rights as Text: Chapter 2, “Constitutional Democracy: Pro- Englishmen. Controversy between the American col- moting Liberty and Self-Government,” pp. onists and the English developed in the aftermath of 37–48 the French and Indian War, when the British govern- ment sought to impose several new taxes in order to Declaration of Independence, Appendix A raise revenue. The British first enacted the Stamp Act, then the Townshend Act, and then a tax on tea. Video: “The American Experiment” Because they had no representatives in the English Parliament, the colonists were convinced that these taxes violated the principle of “no taxation without Overview representation,” a right recognized by Englishmen. The colonists met together to articulate their griev- Events like the Watergate break-in during the Nixon ances against the British crown at the First Continen- Administration demonstrate that Americans still tal Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. -

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

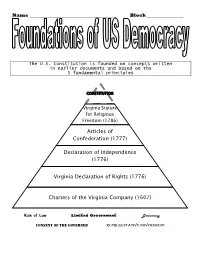

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3.