The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, 37 Case W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

History and Structure of Article Iii

THE HISTORY AND STRUCTURE OF ARTICLE III DANIEL J. MELTZERt In his present article and two that preceded it,' Akhil Amar takes issue with what has come to be regarded as the traditional view of article III-that Congress has plenary authority over federal court jurisdiction. According to that view, Congress may deprive the lower federal courts, the Supreme Court, or all federal courts of jurisdic- tion over any cases within the federal judicial power, excepting only 2 those few that fall within the Supreme Court's original jurisdiction. Amar's powerful challenge to this tradition resembles two other t Professor of Law, Harvard University. A.B. 1972, J.D. 1975, Harvard University. I am grateful to Dick Fallon, Willy Fletcher, Gerry Gunther, and David Shapiro for their encouragement and perceptive comments, and to Matt Kreeger and Sylvia Quast for helpful suggestions and tireless research assistance. Special thanks go to Akhil Amar, whose careful and probing criticism saved me from errors and clarified my own thinking, even though he did not quite convert me. 1 See Amar, Marbury, Section 13, and the OriginalJurisdiction of the Supreme Court, 56 U. CHI. L. REv. 443 (1989) [hereinafter Amar, OriginalJurisdiction]; Amar, A Neo- FederalistFiew ofArticle III: Separatingthe Two Tiers of FederalJurisdiction,65 B.U.L. REv. 205 (1985) [hereinafter Amar, Neo-Federalist View]. 2 See, e.g., Bator, CongressionalPower Over the Jurisdiction of the Federal Courts, 27 VILL. L. REV. 1030, 1030-31 (1982); Gunther, Congressional Power to Curtail Federal CourtJurisdiction: An Opinionated Guide to the Ongoing Debate, 36 STAN. L. REV. 895, 901- 10 (1984); Redish, Congressional Power to Regulate Supreme Court Appellate Jurisdiction Under the Exceptions Clause: An Internal and External Examination, 27 VILL. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

Report to the Attorney General Economic Liberties Protected by the Constitution

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. .. U.S. Department of JustIce Office of Legal Policy ]Report to the Attorney General Economic Liberties Protected by the Constitution March 16, 1988 ~ ~ 115093 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Ponnission to reproduce this ~material has been granted by. PubI1C Domain/Office of Legal Poli_co±y________ _ to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the ~ht owner. REPORT TO THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ON ECONOMIC LIBERTIES PROTECI'ED BY THE CONSTITUTION JAN 1:) Rec'd ACQUISITIONS Office of Legal Policy March 16, 1988 ®fftrr of tqP 1\ttotnPR Qf)puprnl Iht.sltingtnn; ]1. at. znssn In June, 1986, it was my pleasure to host the Attorney General's Conference on Economic Liberties at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. This conference provided an opportunity for a candid exchange of the very different views held by prominent legal scholars on the scope of constitutional j"rotections afforded to economic rights. The conference served as a catalyst for increased discussion of these issues both within the Department and outside it. The present study, "Economic Liberties Protected by the Constitution," is a further contribution to that discussion. It was prepared by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Policy, which functions as a policy development staff for the Department and undertakes comprehensive analyses of contemporary legal issues. -

The President's Power to Execute the Laws

Article The President's Power To Execute the Laws Steven G. Calabresit and Saikrishna B. Prakash" CONTENTS I. M ETHODOLOGY ............................................ 550 A. The Primacy of the Constitutional Text ........................ 551 B. The Source of Confusion Regarding Originalisin ................. 556 C. More on Whose Original Understanding Counts and Why ........... 558 II. THE TEXTUAL CASE FOR A TRINITY OF POWERS AND OF PERSONNEL ...... 559 A. The ConstitutionalText: An Exclusive Trinity of Powers ............ 560 B. The Textual Case for Unenunterated Powers of Government Is Much Harder To Make than the Case for Unenumnerated Individual Rights .... 564 C. Three Types of Institutions and Personnel ...................... 566 D. Why the Constitutional Trinity Leads to a Strongly Unitary Executive ... 568 Associate Professor, Northwestern University School of Law. B.A.. Yale University, 1980, 1 D, Yale University, 1983. B.A., Stanford University. 1990; J.D.. Yale University, 1993. The authors arc very grateful for the many helpful comments and suggestions of Akhil Reed Amar. Perry Bechky. John Harrison, Gary Lawson. Lawrence Lessig, Michael W. McConnell. Thomas W. Merill. Geoffrey P. Miller. Henry P Monaghan. Alex Y.K. Oh,Michael J.Perry, Martin H. Redish. Peter L. Strauss. Cass R.Sunstein. Mary S Tyler, and Cornelius A. Vermeule. We particularly thank Larry Lessig and Cass Sunstein for graciously shanng with us numerous early drafts of their article. Finally. we wish to note that this Article is the synthesis of two separate manuscripts prepared by each of us in response to Professors Lessig and Sunstei. Professor Calabresi's manuscript developed the originalist textual arguments for the unitary Executive, and Mr Prakash's manuscript developed the pre- and post-ratification histoncal arguments. -

The American Experiment

The American2 Experiment Assignment government, where majority desires have an even greater impact on the government. This lesson is based on information in the following Although these ideas are associated with the devel- text selections and video. Carefully read and review opment of the U.S. Constitution, they have their roots all of the materials before taking the practice test. in the preceding colonial and revolutionary experi- The key terms, focus points, and practice test are in- ences in America. The colonists’ English heritage had tended to help ensure mastery of the essential politi- stressed the ideas of both limited government and cal issues surrounding the background and creation self-government. To a large extent, the American rev- of the U.S. Constitution. olutionaries were seeking to retain what they had tra- ditionally understood to be their rights as Text: Chapter 2, “Constitutional Democracy: Pro- Englishmen. Controversy between the American col- moting Liberty and Self-Government,” pp. onists and the English developed in the aftermath of 37–48 the French and Indian War, when the British govern- ment sought to impose several new taxes in order to Declaration of Independence, Appendix A raise revenue. The British first enacted the Stamp Act, then the Townshend Act, and then a tax on tea. Video: “The American Experiment” Because they had no representatives in the English Parliament, the colonists were convinced that these taxes violated the principle of “no taxation without Overview representation,” a right recognized by Englishmen. The colonists met together to articulate their griev- Events like the Watergate break-in during the Nixon ances against the British crown at the First Continen- Administration demonstrate that Americans still tal Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. -

The Other Madison Problem

THE OTHER MADISON PROBLEM David S. Schwartz* & John Mikhail** The conventional view of legal scholars and historians is that James Madison was the “father” or “major architect” of the Constitution, whose unrivaled authority entitles his interpretations of the Constitution to special weight and consideration. This view greatly exaggerates Madison’s contribution to the framing of the Constitution and the quality of his insight into the main problem of federalism that the Framers tried to solve. Perhaps most significantly, it obstructs our view of alternative interpretations of the original Constitution with which Madison disagreed. Examining Madison’s writings and speeches between the spring and fall of 1787, we argue, first, that Madison’s reputation as the father of the Constitution is unwarranted. Madison’s supposedly unparalleled preparation for the Constitutional Convention and his purported authorship of the Virginia plan are unsupported by the historical record. The ideas Madison expressed in his surprisingly limited pre-Convention writings were either widely shared or, where more peculiar to him, rejected by the Convention. Moreover, virtually all of the actual drafting of the Constitution was done by other delegates, principally James Wilson and Gouverneur Morris. Second, we argue that Madison’s recorded thought in this critical 1787 period fails to establish him as a particularly keen or authoritative interpreter of the Constitution. Focused myopically on the supposed imperative of blocking bad state laws, Madison failed to diagnose the central problem of federalism that was clear to many of his peers: the need to empower the national government to regulate the people directly. Whereas Madison clung to the idea of a national government controlling the states through a national legislative veto, the Convention settled on a decidedly non-Madisonian approach of bypassing the states by directly regulating the people and controlling bad state laws indirectly through the combination of federal supremacy and preemption. -

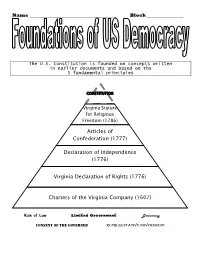

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3. -

The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness Carli N

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 7 | Issue 2 2015 The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness Carli N. Conklin Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, Political Theory Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Carli N. Conklin, The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness, 7 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 195 (2015). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol7/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS CARLI N. CONKLIN ABSTRACT Scholars have long struggled to define the meaning of the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence. The most common understandings suggest either that the phrase is a direct substitution for John Locke’s conception of property or that the phrase is a rhetorical flourish that conveys no substantive meaning. Yet, property and the pursuit of happiness were listed as distinct—not synonymous— rights in eighteenth-century writings. Furthermore, the very inclusion of “the pursuit of happiness” as one of only three unalienable rights enumerated in the Declaration suggests that the drafters must have meant something substantive when they included the phrase in the text. -

American Ideas About the Rights of Man and How a Government Should Operate

American Ideas About the Rights of Man and How A Government Should Operate The Framers of the Constitution were inspired by the following documents and people. Magna Carta (1215) In early 1200’s King John of England began to treat his nobles in ways they felt were unfair. He taxed without asking permission, and put them in jail and took their property without a trial if they refused to pay the taxes. Magna Carta (1215) Many of the Nobles banded together to resist the king’s efforts to take away rights they thought were theirs. They met the king in a place called Runnymeade and forced him to sign a document called the Magna Carta or Great Charter. Magna Carta (1215) The Magna Carta put in writing ideas that are important to our ideas of democracy and rights. 1. Laws that even Kings have to obey. 2. No taxation except by legal means. 3. Right to a fair trial. Mayflower Compact (1620) When the Puritans left England to come to America to escape religious persecution, they were blown off course and landed in Massachusetts, which was outside a colony where there was government. They signed an agreement to establish a government and abide by the laws they made. Mayflower Compact (1630) The Mayflower Compact established these ideas: 1. Established self government and majority rule. 2. A King is not necessary to have laws. 3. Laws can be made by the people for the good of the colony. English Bill of Rights (1689) King James II dismissed parliament and tried to restrict the rights of people in England. -

The Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention Woman (to Benjamin Franklin): “Well, Doctor, what have we got—a Republic or a Monarchy?” Benjamin Franklin: "A Republic, if you can keep it.” - McHenry, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, Oil on Canvas, Howard Chandler Christy The hundred day debate known as the Constitutional Convention was one of the most momentous occurrences in United States Constitutional History, and the events that would take place in the Pennsylvania State House during that time would set the United States on the course towards becoming a true Constitutional Republic. The Convention took place from May 14 to September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The point of the event was decide how America was going to be governed. Although the Convention had been officially called to revise the existing Articles of Confederation, many delegates had much bigger plans. Men like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton wanted to create a new government rather than fix the existing one. The delegates elected George Washington to preside over the Convention. 70 Delegates had been appointed by the original states to attend the Constitutional Convention, but only 55 were able to be there. Rhode Island was the only state to not send any delegates at all. As history played out, the result of the Constitutional Convention was the United States Constitution, but it wasn't an easy path. The drafting process was grueling. They wanted the supreme law of the United States to be perfect. The first two months of the Convention saw fierce debate over the 15 points of the "Virginia Plan" which had been proposed by Madison as an upgrade to the Articles of Confederation. -

Presidential Removal: the Marbury Problem and the Madison Solutions

Fordham Law Review Volume 89 Issue 5 Article 14 2021 Presidential Removal: The Marbury Problem and the Madison Solutions Jed Handelsman Shugerman Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jed Handelsman Shugerman, Presidential Removal: The Marbury Problem and the Madison Solutions, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2085 (2021). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol89/iss5/14 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL: THE MARBURY PROBLEM AND THE MADISON SOLUTIONS Jed Handelsman Shugerman* [Marbury’s] appointment was not revocable; but vested in the officer legal rights, which are protected by the laws of his country. To withhold his commission, therefore, is an act deemed by the court not warranted by law, but violative of a vested legal right. —Chief Justice John Marshall1 INTRODUCTION This sentence from Marbury v. Madison2 is both a potential argument against the unitary executive theory of total executive removal power . and in favor of it. Why was William Marbury’s office as justice of the peace irrevocable? Why didn’t President Thomas Jefferson just fire Marbury and moot this case? On the other hand, this sentence also seems to tell us that “vested” rights are irrevocable, so perhaps vested powers are also irrevocable (or “indefeasible” by Congress and not conditional by legislation)? Here is another sentence relying on this absolutist connotation of “vested”: “Under our Constitution, the ‘executive Power’—all of it—is ‘vested in a President,’ who must ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.’”3 In Seila Law LLC v.