Annotated Wisconsin Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

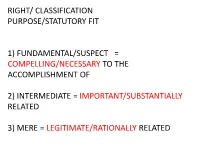

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Disentangling the Sixth Amendment

ARTICLES * DISENTANGLING THE SIXTH AMENDMENT Sanjay Chhablani** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................488 I. THE PATH TRAVELLED: A HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE COURT’S SIXTH AMENDMENT JURISPRUDENCE......................492 II. AT A CROSSROADS: THE RECENT DISENTANGLEMENT OF THE SIXTH AMENDMENT .......................................................505 A. The “All Criminal Prosecutions” Predicate....................505 B. Right of Confrontation ...................................................512 III. THE ROAD AHEAD: ENTANGLEMENTS YET TO BE UNDONE.................................................................................516 A. The “All Criminal Prosecutions” Predicate....................516 B. The Right to Compulsory Process ..................................523 C. The Right to a Public Trial .............................................528 D. The Right to a Speedy Trial............................................533 E. The Right to Confrontation............................................538 F. The Right to Assistance of Counsel ................................541 CONCLUSION.................................................................................548 APPENDIX A: FEDERAL CRIMES AT THE TIME THE SIXTH AMENDMENT WAS RATIFIED...................................................549 * © 2008 Sanjay Chhablani. All rights reserved. ** Assistant Professor, Syracuse University College of Law. I owe a debt of gratitude to Akhil Amar, David Driesen, Keith Bybee, and Gregory -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

AAUP Annual Legal Update August, 2020

AAUP Annual Legal Update August, 2020 Aaron Nisenson, Senior Counsel American Association of University Professors I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 II. First Amendment and Speech Rights ...................................................................................... 5 A. Garcetti / Citizen Speech ......................................................................................................... 5 Lane v. Franks, 134 S. Ct. 2369 (2014) .................................................................................. 5 B. Faculty Speech ......................................................................................................................... 5 Demers v. Austin, 746 F.3d 402 (9th Cir. 2014) .................................................................... 5 Wetherbe v. Tex. Tech Univ. Sys., 699 F. Appx 297 (5th Cir. 2017); Wetherbe v. Goebel, No. 07-16-00179-CV, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 1676 (Mar. 6, 2018) ................................... 5 Buchanan v. Alexander, 919 F.3d 847 (5th Cir. March 22, 2019) ......................................... 6 EXECUTIVE ORDER, Improving Free Inquiry, Transparency, and Accountability at Colleges and Universities (D. Trump March 21, 2019) ........................................................ 8 C. Union Speech............................................................................................................................ 9 Meade v. Moraine Valley Cmty. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

The Speedy Trial Clause and Parallel State-Federal Prosecutions

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 71 Issue 1 Article 10 2020 The Speedy Trial Clause and Parallel State-Federal Prosecutions Ryan Kerfoot Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ryan Kerfoot, The Speedy Trial Clause and Parallel State-Federal Prosecutions, 71 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 325 (2020) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol71/iss1/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 71·Issue 1·2020 — Note — The Speedy Trial Clause and Parallel State-Federal Prosecutions Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 325 I. Background of the Speedy Trial Clause............................... 328 II. Interests in Speedy Parallel Prosecutions ........................... 332 A. Federal-State Separation ..................................................................... 333 B. Prosecutorial Diligence ....................................................................... 336 C. Logistical Concerns ............................................................................. 337 III. Practical Effect of Each Circuit’s Approach ...................... 338 A. Bright-Line -

19-267 Our Lady of Guadalupe School V. Morrissey-Berru (07/08/2020)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2019 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL v. MORRISSEY- BERRU CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–267. Argued May 11, 2020—Decided July 8, 2020* The First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions “to de- cide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.” Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral of Russian Orthodox Church in North America, 344 U. S. 94, 116. Applying this principle, this Court held in Hosanna- Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, 565 U. S. 171, that the First Amendment barred a court from entertaining an employment discrimination claim brought by an elementary school teacher, Cheryl Perich, against the religious school where she taught. Adopting the so-called “ministerial exception” to laws governing the employment relationship between a religious institution and certain key employees, the Court found relevant Perich’s title as a “Minister of Religion, Commissioned,” her educational training, and her respon- sibility to teach religion and participate with students in religious ac- tivities. Id., at 190–191. -

Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 1 Article 12 2016 Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker v. Wingo Test Seth Osnowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Seth Osnowitz, Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker v. Wingo Test, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 273 (2016) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss1/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 1·2016 Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Barker v. Wingo Test Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 273 I. Background and Policy of Sixth Amendment Right to Speedy Trial .......................................................................... 275 A. History of Speedy Trial Jurisprudence ............................................ 276 B. Policy Considerations and the “Demand-Waiver Rule”..................... 279 II. The Barker Test and Defendants’ Assertion of the Right to a Speedy Trial .................................................................. 282 A. Rejection of the -

Case 1:20-Cr-00188-JSR Document 208 Filed 03/01/21 Page 1 of 25

Case 1:20-cr-00188-JSR Document 208 Filed 03/01/21 Page 1 of 25 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -----------------------------------x UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : : : 20-cr-188 (JSR) -v- : : OPINION & ORDER HAMID AKHAVAN & RUBEN WEIGAND, : : Defendants. : : -----------------------------------x JED S. RAKOFF, U.S.D.J. This case began less than one year ago, on March 9, 2020, when a grand jury returned indictments against Ruben Weigand and Hamid (“Ray”) Akhavan for conspiracy to commit bank fraud. Today, the Court will empanel a jury to try the case. The intervening year has been challenging. Just two days after the indictments were returned, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic.1 Two days later, President Trump announced that “[t]o unleash the full power of the federal government, in this effort today I am officially declaring a national emergency. Two very big words.”2 Since then, the total 1 James Keaton, et al., WHO Declares Coronavirus a Pandemic, Urges Aggressive Action, Reuters (Mar. 12, 2020), https://apnews.com/article/52e12ca90c55b6e0c398d134a2cc286e. 2 The New York Times, Two Very Big Words: Trump Announces National Emergency for Coronavirus (Mar. 13, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/video/us/politics/100000007032704/trump- coronavirus-live.html. 1 Case 1:20-cr-00188-JSR Document 208 Filed 03/01/21 Page 2 of 25 number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has surpassed 113 million worldwide, and more than 2.5 million people have died.3 In the United States alone, there have been more than 28 million confirmed cases, and more than half a million people have died.4 Recognizing the importance of the defendants’ and the public’s right to a speedy trial, and despite the complexity of this case and the many difficulties generated by the pandemic, the Court has expended considerable effort to bring the case swiftly and safely to trial. -

The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: the Gentile V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 43 1993 The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision Suzanne F. Day Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Suzanne F. Day, The Supreme Court's Attack on Attorneys' Freedom of Expression: The Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada Decision, 43 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1347 (1993) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol43/iss4/43 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE SUPREME COURT'S AITACK ON ATTORNEYS' FREEDOM OF ExPRESSION: THE GENTILE v. STATE BAR OF NEVADA DECISION TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............. ............ 1349 A. The Dilemma of the Defense Attorney ....... 1349 B. State Court Rules Restricting Attorney Communication with the Media ............. 1350 11. CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS RAISED BY RESTRICTING PRETRIAL PUBLICITY THROUGH CURBING THE SCOPE OF ATrORNEY SPEECH: THE FAIR TRIAL - FREE PRESS DEBATE ...... ........................ 1351 A. The Sheppard v. Maxwell Decision: The United States Supreme Court's Directive to Trial Court Judges ............................ 1352 B. The Conflicting First Amendment Rights of Attorneys, Sixth Amendment Rights of the Defendant, and the State and Public Interest in the Impartial Administration of Justice ........... 1355 1. What the Amendments Guarantee ......... 1355 2. -

Attorney Solicitation: the Scope of State Regulation After <Em>Primus</Em> and <Em>Ohralik</Em>

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 12 1978 Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik David A. Rabin University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Legal Profession Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Rabin, Attorney Solicitation: The Scope of State Regulation After primus and Ohralik, 12 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 144 (1978). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol12/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTORNEY SOLICITATION: THE SCOPE OF STATE REGULATION AFTER PRIMUS AND OHRALIK Within the past few years, there has been a growing concern both within and without the legal profession-over increasing the layman's access to legal services. Two of the principal means of increasing this access, advertising and solicitation, 1 have long been prohibited by the organized bar, although a few minor exceptions have been allowed. In lff77, the question of the constitutionality of prohibitions against legal advertising was presented to the United States Supreme Court in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona. 2 The Court ruled in a landmark decision that certain types of advertising could not be prohibited, but expressly reserved the question of the con stitutionality of prohibitions against in-person solicitation.3 Eleven months after Bates, the Court decided two attorney solicitation cases, In re Primus4 and Ohra/ik v. -

Exceptions to the First Amendment

Order Code 95-815 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Updated July 29, 2004 Henry Cohen Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Summary The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press....” This language restricts government both more and less than it would if it were applied literally. It restricts government more in that it applies not only to Congress, but to all branches of the federal government, and to all branches of state and local government. It restricts government less in that it provides no protection to some types of speech and only limited protection to others. This report provides an overview of the major exceptions to the First Amendment — of the ways that the Supreme Court has interpreted the guarantee of freedom of speech and press to provide no protection or only limited protection for some types of speech. For example, the Court has decided that the First Amendment provides no protection to obscenity, child pornography, or speech that constitutes “advocacy of the use of force or of law violation ... where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Court has also decided that the First Amendment provides less than full protection to commercial speech, defamation (libel and slander), speech that may be harmful to children, speech broadcast on radio and television, and public employees’ speech.