Thurrock Education Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open PDF 715KB

LBP0018 Written evidence submitted by The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium Education Select Committee Left behind white pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds Inquiry SUBMISSION FROM THE NORTHERN POWERHOUSE EDUCATION CONSORTIUM Introduction and summary of recommendations Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium are a group of organisations with focus on education and disadvantage campaigning in the North of England, including SHINE, Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) and Tutor Trust. This is a joint submission to the inquiry, acting together as ‘The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium’. We make the case that ethnicity is a major factor in the long term disadvantage gap, in particular white working class girls and boys. These issues are highly concentrated in left behind towns and the most deprived communities across the North of England. In the submission, we recommend strong actions for Government in particular: o New smart Opportunity Areas across the North of England. o An Emergency Pupil Premium distribution arrangement for 2020-21, including reform to better tackle long-term disadvantage. o A Catch-up Premium for the return to school. o Support to Northern Universities to provide additional temporary capacity for tutoring, including a key role for recent graduates and students to take part in accredited training. About the Organisations in our consortium SHINE (Support and Help IN Education) are a charity based in Leeds that help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged children across the Northern Powerhouse. Trustees include Lord Jim O’Neill, also a co-founder of SHINE, and Raksha Pattni. The Northern Powerhouse Partnership’s Education Committee works as part of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) focusing on the Education and Skills agenda in the North of England. -

Actuarial Valuation As at 31 March 2019

VALUATION REPORT Essex Pension Fund Actuarial valuation as at 31 March 2019 1 June 2020 Graeme Muir FFA & Colin Dobbie FFA | Barnett Waddingham LLP Introduction We have been asked by Essex County Council, the This report summarises the results of the valuation and is addressed to the administering authority for the Essex Pension Fund administering authority of the Fund. It is not intended to assist any user other than the administering authority in making decisions or for any other (the Fund), to carry out an actuarial valuation of the purpose and neither we nor Barnett Waddingham LLP accept liability to third Fund as at 31 March 2019. The Fund is part of the parties in relation to this advice. Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS), a defined This advice complies with Technical Actuarial Standards (TASs) issued by the benefit statutory scheme administered in accordance Financial Reporting Council – in particular TAS 100: Principles for Technical with the Local Government Pension Scheme Actuarial Work and TAS 300: Pensions. Regulations 2013 (the Regulations) as amended. We would be pleased to discuss any aspect of this report in more detail. The purpose of the valuation is to review the financial position of the Fund and to set appropriate contribution rates for each employer in the Fund for the period from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2023 as required under Regulation 62 of the Regulations. Contributions are set to cover any shortfall between the assumed cost of providing benefits built up by members at the valuation date and the assets held by the Fund and also to cover the cost of benefits that active members will build up in the future. -

September 2017

Secondary Admission Information September 2017 Information for parents applying for a school place Apply online at thurrock.gov.uk/admissions Information for parents applying for a secondary school place Apply online at thurrock.gov.uk/admissions Foreword Starting secondary school is a very important Thurrock secondary schools offer a range of time in a child’s life and here in Thurrock specialisms and each will have something to Council we appreciate what a worrying time this offer your child. Thurrock secondary schools is for parents. We are determined to make this achieve well at GCSE in comparison to national as straightforward and worry free as we can. standards and are amongst the most improved The information that follows is designed to help schools in the country. you make informed decisions when you come to make an application for a secondary school I wish your child an enjoyable and fruitful time place. at secondary school and every success for the future. 3 Our online application facility has proved to be very popular and almost 9 out of 10 Please go online at applications are now made this way. The thurrock.gov.uk/admissions and advantages are that it is immediate, you will get follow the instructions on screen. automatic confirmation your application has been received and it will remove any risk of an application being delayed or lost in the post. Rory Patterson Apply online and you will, from 12.30am on Corporate Director of Children’s Services 1 March 2017, be able to check online which school place has been allocated. -

William Edwards Marshalls Park Nat Av 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 Eng & Maths 63% 72% 64% 74% 62% 60% 66% 4+ Attainment 8 44 46 45 49 41 40 45

Opening September 2020 www.orsettheathacademy.org.uk SWECET established in April 2015. Currently the trust is responsible for William Edwards School, Deneholm Primary, Stifford Clays Primary School, Chadwell St Mary Primary School and Marshalls Park Academy. 1204 on roll HT – Simon Bell Steve Munday – Chief Executive Officer Deneholm Primary Chadwell St Mary Primary 250 on roll 419 on roll Head of School – Lauren Robinson Head of School – Jack Lloyd ‘Approval to open’ has now been granted by the Department for Education to open Orsett Heath in September 2020 • 120 places available in year 7 for September 2020 • You can apply for a place up to 19th December • Applications for Orsett Heath are separate to LA process • The bespoke school building at TRFC is underway with a completion date in August 2020 Strongest ever collective results at KS2 and KS4 in 2019 SWECET Secondary Schools William Edwards Marshalls Park Nat Av 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 Eng & Maths 63% 72% 64% 74% 62% 60% 66% 4+ Attainment 8 44 46 45 49 41 40 45 SWECET Primary Schools Chadwell St Mary Deneholm Stifford Clays National 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 KS2 Reading, Writing 69% and Maths Expected+% 65% 59% 57% 79% 61% 76% 78% 57% 52% Contextually high achievement 2019 GCSE Results All Pupils Percentage achieving Eng & Cohort English Maths Establishment Name Maths Grade 4+ Grade 4+ Grade 4+ Name KS4 Harris Academy Chafford Hundred 170 88.2% 84.7% 78.2% William Edwards 242 88.0% 74.0% 73.0% St Clere's School 228 81.1% 78.9% 73.0% Grays Convent 121 94.2% 71.1% 70.2% Hassenbrook Academy 81 64.2% 70.4% 56.8% The Gateway Academy 198 63.6% 66.2% 54.5% Gable Hall School 235 68.1% 59.6% 54.4% The Ockendon Academy 198 65.2% 56.6% 50.5% The Hathaway Academy 144 59.0% 61.1% 50.0% Ormiston Park Academy 95 61.1% 56.8% 48.4% Thurrock 2019 1712 74.3% 68.4% 62.2% National (All Schools) 2018 59.4% • The curriculum offer and breadth of experience will mirror that at William Edwards. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

The Gateway Primary Free School Bid May 2011

The Gateway Primary Free School Bid May 2011 Contents Section 1: page Section 4: page Section 5: page Section 9: page Applicant Details 5 Educational Plan 17 Evidence of Demand 35 Annexes 53 Details of Company Limited by Guarantee 6 Structure of the School 18 Evidence of Parental Demand 36 1. Ofsted Inspection 2009 Main Contact 6 Learning Community Structure 19 Context 36 2. Ofsted Team inspection 2011 Members and Directors 6 Gateway Primary Free School: Structure 19 Local Authority Consultation 37 3. Proposed site and catchment area of the Related Organisations 7 Gateway Primary Free School: Staffing Structure 20 Statutory Consultation 37 Gateway Primary Free School Declaration to be Signed by Company Director 7 Admissions 20 Plan 37 4. Gateway Academy Accounts 2008-09 5. Gateway Academy Accounts 2009-10 Gateway Primary Free School Summary 8 Process of Application 21 Consideration of Applications 21 Section 6: 6. Gateway Academy Articles of Association Section 2: Process where the Gateway Primary Free School 21 Organisation Capacity and Capability 7. Gateway Academy Memorandum of Association Outline of the School 9 is over subscribed 39 8. Local Authority letter of confirmation for the need Mid year admissions and admissions for Year Groups 22 for a new primary school Capacity and Capability to set up a school 40 other than Reception 9. Survey of Local Opinion Governance 41 Section 3: Arrangements for Appeals Panels 22 10. Gateway Primary Free School proposed budget Finance 41 Educational Vision 11 Consultation 22 2012/13 Gateway Academy Accounts/Articles and 41 The wider vision of the free school we are confident 13 Determination and Publication of Admission 22 11. -

Grand Final 2020

GRAND FINAL 2020 Delivered by In partnership with grandfinal.online 1 WELCOME It has been an extraordinary year for everyone. The way that we live, work and learn has changed completely and many of us have faced new challenges – including the young people that are speaking tonight. They have each taken part in Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! – a programme which reaches over 20,000 young people a year. They have had a full day of training in communica�on skills and public speaking and have gone on to win either a Regional Final or Digital Final and earn their place here tonight. Every speaker has an important and inspiring message to share with us, and we are delighted to be able to host them at this virtual event. A message from A message from Sir Jack Petchey CBE Fiona Wilkinson Founder Patron Chair The Jack Petchey Founda�on Speakers Trust Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! At Speakers Trust we believe that helps young people find their voice speaking up is the first step to and gives them the skills and changing the world. Each of the young confidence to make a real difference people speaking tonight has an in the world. I feel inspired by each and every one of them. important message to share with us. Jack Petchey’s “Speak Public speaking is a skill you can use anywhere, whether in a Out” Challenge! has given them the ability and opportunity to classroom, an interview or in the workplace. I am so proud of share this message - and it has given us the opportunity to be all our finalists speaking tonight and of how far you have come. -

A OS Report Multi Academy Trust Relationships(I)

10 November 2015 ITEM: 6 Children’s Services Overview and Scrutiny Committee Multi Academy Trust Relationships Wards and communities affected: Key Decision: All All Report of: Carmel Littleton - Director of Children’s Services Roger Edwardson – Interim Strategic Leader School Improvement, Learning and Skills Accountable Head of Service: Roger Edwardson, Interim Strategic Leader School Improvement, Learning and Skills Accountable Director: Carmel Littleton, Director of Children’s Services This report is public Executive Summary There are thirty-six academies in Thurrock, fourteen of which are sponsored and two are Free Schools. There are currently no schools in the process of converting. The Children’s Business and Improvement Team in Children’s Services, provide a service to schools to support them through the process efficiently and professionally. The Multi-Academy Trust (MAT) Model A Multi Agency Trust is formed when a number of schools who wish to convert or have already converted to academy status, come together as one legal entity, either in a cluster or as part of a bigger existing organisation. The MAT is a single legal entirety with two layers of governance; an overarching academy trust governed by foundation members and a board of directors or governors. There are ten Multi-Academy Trusts as well as 8 academies that are either part of an ‘empty MAT’ or are stand alone. An ‘empty MAT’ has yet to recruit academies to join, either because the MAT founder school decides it is not yet ready to support another school or have not yet approached. E.g. Belmont Castle Academy and Tudor Court Primary. -

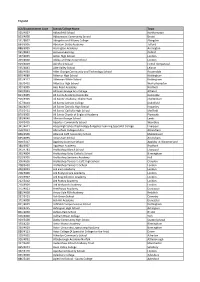

Remote Desktop Redirected Printer

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 928/4007 Abbeyfield School Northampton 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 931/8007 Abingdon and Witney College Abingdon 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 209/4600 Addey and Stanhope School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange Community and Technology School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 336/5402 Aldersley High School Wolverhampton 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 357/4604 All Saints Catholic College Dukinfield 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 373/5401 All Saints' Catholic High School Sheffield 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 909/5407 Appleby Grammar School Appleby-in-Westmorland 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4781 Archbishop Blanch School Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 -

The Gateway Primary Free School Author: Department for Education (Dfe)

Title: The Gateway Primary Free School Author: Department for Education (DfE) Impact Assessment – Section 9 Academies Act Duty 1. Section 9 of the Academies Act places a duty upon the Secretary of State to take into account what the impact of establishing the new school is likely to be on maintained schools, Academies and institutions within the further education sector in the area in which the school is situated. Background 2. The Gateway Primary Free School will be co-located with the existing Gateway Academy in Tilbury, Essex. At capacity, the school will accommodate 630 pupils from Reception to Year 6. It will open in September 2012 with 90 Year 6 pupils. From September 2013, pupils will be present in all years from Reception to Year 6. 3. The proposal was submitted by the Gateway Academy (an outstanding secondary Academy) with strong backing from the Ormiston Trust, the Academy’s sponsor. The success of the Gateway Academy has generated strong parental support for a primary school linked to the Academy and has the backing of the Local Authority. The school will provide a traditional primary curriculum with pupils benefitting from the shared facilities and teaching with e Academy. 4. The school has currently received applications from and offered provisional places to 50 pupils, although we expect that number to increase to around 70 by the time the school opens in September. 5. The Gateway Academy Trust is in the process of becoming a Multi- Academy Trust. It will establish a single Governing Body to oversee four schools that will be part of the Gateway Learning Community. -

Thurrock Schools' Forum, 27 June 2019

THURROCK SCHOOLS’ FORUM 27th June 2019 at 9.00a.m Thurrock Adult Community College, Room 10, Richmond Road, Grays, RM17 6DN Contact: 01375 372476 AGENDA Primary Academies Headteacher – Kenningtons Ms J Sawtell-Haynes Headteacher – Abbotts Primary Mrs L James Principal – Woodside Academy Mr E Caines – Vice Chair Headteacher – Giffards Primary Mrs N Haslam-Davis CEO - Catalyst Academies Trust Mr T Parfett Headteacher- East Tilbury Primary and Nursery Mrs L Coates Primary Maintained Schools Headteacher – Aveley Primary Miss N Shadbolt Secondary Academies CEO – Osborne Co-operative Academy Trust Mr P Griffiths – Chair Principal – Harris Academy Chafford Hundred Mrs N Graham CEO - South West Essex Community Education Mr S Munday Trust CEO – ORTU Federation Ltd Dr S Asong Governor – Hathaway Academy Mr S Sweeting Secondary Maintained Schools Headteacher – Grays Convent Mrs P Johnson Special Maintained Schools Headteacher – Treetops School Mr P Smith Special Academy Headteacher-Beacon Hill Academy Ms S Hewitt Olive AP Academy Executive Headteacher Ms E Hinds Non School Members Diocese of Brentwood Mrs M Shepherd Diocese of Chelmsford Miss S Jones 0-11 Representative Ms A Jones 11-19 Representative Mr D Pearson Portfolio Holder – Children and Learning Cllr J Halden 1 Contact Jan Walker. Children’s Services (01375 652559) Children, Education & Families, Civic Offices, New Road, Grays, Essex RM17 6SL Teresa Lydon Minutes: Introductory Items Item Item Time Guide 1. Welcome from Chair 1 min 2. Apologies for Absence 2 mins Agreement of agenda, time-guide and notification of ‘Any 3. 2 mins Other Business’ Items for Decision Union Facility Time 4. 10 mins • Presented by Sue Lamkin Dedicated Schools Grant 2018/19 Outturn and 2019-20 Update 5. -

Pupil Place Plan Update

0 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 PUPIL PLACE PLANNING (PPP) ............................................................................... 3 CONTEXT .................................................................................................................. 4 SCHOOLS AND PLANNING AREAS ......................................................................... 6 PRIMARY FORECASTS ............................................................................................ 9 SECONDARY FORECASTS .................................................................................... 21 COUNCIL WIDE ISSUES ......................................................................................... 28 ANNEX 1: PUPIL PLACE FORECASTING METHODOLOGY ................................. 29 NEED TO DISCUSS WITH SARAH WILLIAMS .......... Error! Bookmark not defined. ANNEX 2: SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS AND DISABILITY (SEND) ............... 32 ANNEX 3: PROVISION FOR PUPILS OUT OF SCHOOL........................................ 34 ANNEX 4: POST 16 PROVISION ............................................................................. 35 ANNEX 5: MAP PRIMARY PHASE PLANNING AREAS .......................................... 37 ANNEX 6: MAP SECONDARY PHASE PLANNING AREAS ................................... 38 ANNEX 7: PRIMARY FORECAST RECEPTION ...................................................... 39 ANNEX 8: PRIMARY FORECAST WHOLE SCHOOL ............................................