Explicit Memory and Cognition in Monkeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

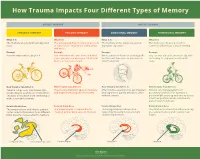

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

TRAUMATIC AMNESIA a Dissociative Survival Mechanism

TRAUMATIC AMNESIA a dissociative survival mechanism Dr. Muriel Salmona, psychiatrist, Paris, January 19, 2018 I - Presentation Complete or fragmented traumatic amnesia is a common memory disorder found in victims of violence. Numerous clinical studies have described this well- known phenomenon since the beginning of the twentieth century, when the first systematic studies explored amnesia among traumatized combat soldiers, and later among victims of sexual violence. Studies found almost 40 % complete amnesia among these participants, and 60% partial amnesia when childhood sexual abuse was concerned (Brière 1993, Williams 1994, IVSEA 2015). These amnesias are psychotraumatic consequences of violence. They are neuro- psychological survival mechanisms based on dissociation (Van der Kolk, 1995, 2001). Since 2015, dissociative traumatic amnesias have been recognized as a defining criterium for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (DSM-5, 2015). They can last several decades and lead to amnesia for entire sections of childhood, with almost no retrievable memory, which results in a painful impression of having no past, nor landmarks. When amnesia fades away, traumatic memories most often return brutally, invasively, as uncontrolled, unintegrated, fragmented traumatic memories (flashbacks, nightmares) and trigger re-experiences of violence with identitical distress and sensations, and a vividness as if the trauma was happening all over again. Care professionals should be better acquainted with these phenomena in order to improve how they care for the victims, by treating such reminiscences without confusing them with hallucinations, identifying violence, and its psychotraumatic consequences for the victims. Similarly, justice professionals, when faced with sexual violence complaints after recovered memories, should be more aware of the reality of such frequent memory disorder. -

Rethinking Trauma

How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Daniel Siegel, MD - Main Session - pg. 1 Rethinking Trauma How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma the Main Session with Daniel Siegel, MD and Ruth Buczynski, PhD National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Daniel Siegel, MD - Main Session - pg. 2 Rethinking Trauma: Daniel Siegel, MD How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Table of Contents (click to go to a page) How To Define What Happens in the Brain During Trauma ................................... 3 The Optimally Functioning vs. Traumatized Brain as Defined by FACES ................. 4 How Age Affects the Impact of Trauma on the Brain .............................................. 7 Trauma Leads to the Chemical Release of Cortisol and Adrenaline ....................... 8 How Trauma Impairs the Brain’s Memory Systems ............................................... 10 Why the Brain’s Developmental Period Is Crucial to Working with Trauma ............ 11 The Layers of Memory and Encoding Implicit Memory .......................................... 13 The Retrieval of Implicit Memory and the Experience of Flashback ...................... 15 Putting the Science into Clinical Practice ............................................................... 17 What Happens in the Brain during Dissociation? ................................................... 18 -

Interactions Between Attention and Memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne

Interactions between attention and memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne Attention and memory cannot operate without each other. In form of selective attention to internal representations this review, we discuss two lines of recent evidence that [1,2]. support this interdependence. First, memory has a limited capacity, and thus attention determines what will be Classic psychologists such as William James stated long encoded. Division of attention during encoding prevents the ago that ‘we cannot deny that an object once attended to formation of conscious memories, although the role of attention will remain in the memory, while one inattentively in formation of unconscious memories is more complex. Such allowed to pass will leave no traces behind’ [3]. More memories can be encoded even when there is another recently, leading neuroscientists such as Eric Kandel have concurrent task, but the stimuli that are to be encoded must be stated that one of the most important problems for 21st selected from among other competing stimuli. Second, century neuroscience is to understand how attention memory from past experience guides what should be attended. regulates the processes that stabilize experiential mem- Brain areas that are important for memory, such as the ories [4]. Here, we review studies from the past two years hippocampus and medial temporal lobe structures, are that reveal progress towards understanding the inter- recruited in attention tasks, and memory directly affects frontal- actions between attention and memory in neural systems. parietal networks involved in spatial orienting. Thus, exploring the interactions between attention and memory can provide Attention at encoding new insights into these fundamental topics of cognitive A major question in many people’s minds is how to neuroscience. -

How Do We Learn from Experience?

TSI Graphics: Worth—Kolb/Whishaw: An Introduction to Brain and Behavior C H A P T E R 13 How Do We Learn from Experience? What Are Learning and Memory? The Structural Basis of Brain Studying Memory in the Laboratory Plasticity Two Types of Memory Measuring Synaptic Change What Makes Explicit and Implicit Enriched Experience and Plasticity Memory Different? Sensory or Motor Training and Plasticity Plasticity, Hormones, Trophic Factors, and Drugs Dissociating Memory Circuits Focus on Disorders: Patient Boswell’s Amnesia Recovery from Brain Injury The Three-Legged Cat Solution Neural Systems Underlying The New-Circuit Solution Explicit and Implicit Memories The Lost-Neuron-Replacement Solution A Neural Circuit for Explicit Memories Focus on Disorders: Alzheimer’s Disease A Neural Circuit for Implicit Memories Focus on Disorders: Korsakoff’s Syndrome A Neural Circuit for Emotional Memories Dimitri Messinis/AP Photo Micrograph: Oliver Meckes/Ottawa/Photo Researchers 488 ■ D TSI Graphics: Worth—Kolb/Whishaw: An Introduction to Brain and Behavior onna was born on June 14, 1933. Her memory of Over the ensuing 10 months, Donna regained most of the period from 1933 to 1937 is sketchy, but her motor abilities and language skills, and her spatial abil- D those who knew her as a baby report that she was ities improved significantly. Nonetheless, she was short- like most other infants. At first, she could not talk, walk, or tempered and easily frustrated by the slowness of her use a toilet. Indeed, she did not even seem to recognize her recovery, symptoms that are typical of people with closed father, although her mother seemed more familiar to her. -

CHILDREN's MEMORY, TRAUMATIC MEMORIES and the CHILD WITNESS

CHILD MEMORY, TRAUMATIC MEMORY and the CHILD WITNESS George E. Davis, MD 2017 Children’s Law Institute INTERPRETING THE RESEARCH • The complications of memory study • Test conditions and questions don’t always match real life situations and motivations • Divergent interests • Although broad rules can be proposed for different ages and conditions, reliability depends on the individual case REFERENCES 1. Memory and Suggestibility in the Forensic Interview (Eisen, Quas and Goodman, 2002) 2. Stress, Trauma and Children’s Memory Development (Howe, Goodman and Cicchetti, 2008) 3. Children as Victims, Witnesses, and Offenders (Bottoms, Najdowski and Goodman, 2009) MEMORY PROCESS • MEMORY COMPONENTS – Encoding • PerceptionConstruct • Child age and knowledge – Storage • Combination, sorting, comparison in the hippocampus • Short term, long term and working memory – Retrieval • Reconstruction from associations and neural networks that are frontal and temporal TYPES of MEMORY • TYPES OF MEMORY – Explicit / Declarative / Conscious • Episodic—events • Semantic—facts • Intentional, whether learned or recalled • Organized and encoded by hippocampus and medial temporal – Implicit / Contextual / Unconscious • Procedural—riding a bike, driving to work, tying shoes, etc • Encoded and stored in motor control and brain stem – Conditioned responses—eg, fear of certain people – Autobiographical—the continuous sense of self over time DISSOCIATION • Dissociation is a breakdown in memory, consciousness and sense of self provoked by extreme fear, pain or psychological -

Explicit and Implicit Memory by Richard H

Explicit and Implicit Memory by Richard H. Hall, 1998 Overview As you might suspect, researchers and theorists have extended the basic multi-store model in many ways, among these is the differentiation of different types of long term memories. Perhaps the most fundamental such differentiation is the distinction between explicit and implicit memories (Figure 1). Implicit memories are sometimes referred to as "non-declarative" because an individual is unable to verbally "declare" these memories. Implicit memories are nonconscious, and often involve memories for specific step-by-step procedures, or specific feelings/emotions. For example, your ability to carry out the various processes involved in driving a car are largely nonconscious, they have been "proceduralized". Further, your conditioned emotional response to a "scary" situation is not something that you consciously or verbally recall. On the other hand, explicit memories are conscious memories that can easily be verbalized. They are more complex types of memories because they are often holistic, in that they involve the recall of many different aspects of a situation. In order to consciously recall something, such as your memory of events that occurred yesterday, you not only recall the event, but you also recall the context in which the event occurred, that is, the time of day, the place, and other objects and people that were present, etc. Figure 1. Comparison of Implicit and Explicit Memory Explicit Memory Storage Research, in particular with brain damaged patients such as those suffering from Korsakoff's and the case of HM, indicates that these two fundamental types of long term memory are more than theoretical abstractions. -

Memory Reactivation and Consolidation During Sleep Ken A

Sleep & Memory/Review Memory reactivation and consolidation during sleep Ken A. Paller1 and Joel L. Voss Institute for Neuroscience and Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208-2710, USA Do our memories remain static during sleep, or do they change? We argue here that memory change is not only a natural result of sleep cognition, but further, that such change constitutes a fundamental characteristic of declarative memories. In general, declarative memories change due to retrieval events at various times after initial learning and due to the formation and elaboration of associations with other memories, including memories formed after the initial learning episode. We propose that declarative memories change both during waking and during sleep, and that such change contributes to enhancing binding of the distinct representational components of some memories, and thus to a gradual process of cross-cortical consolidation. As a result of this special form of consolidation, declarative memories can become more cohesive and also more thoroughly integrated with other stored information. Further benefits of this memory reprocessing can include developing complex networks of interrelated memories, aligning memories with long-term strategies and goals, and generating insights based on novel combinations of memory fragments. A variety of research findings are consistent with the hypothesis that cross-cortical consolidation can progress during sleep, although further support is needed, and we suggest some potentially fruitful research directions. Determining how processing during sleep can facilitate memory storage will be an exciting focus of research in the coming years. The idea that memory storage is supported by events that take otherwise intellectually intact. -

Pervasive Influences of Memory Without Awareness of Retrieval Joel L

This article was downloaded by: [Northwestern University] On: 28 July 2012, At: 08:25 Publisher: Psychology Press Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Cognitive Neuroscience Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/pcns20 More than a feeling: Pervasive influences of memory without awareness of retrieval Joel L. Voss a , Heather D. Lucas b & Ken A. Paller b a Department of Medical Social Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA b Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA Accepted author version posted online: 15 Mar 2012. Version of record first published: 30 Mar 2012 To cite this article: Joel L. Voss, Heather D. Lucas & Ken A. Paller (2012): More than a feeling: Pervasive influences of memory without awareness of retrieval, Cognitive Neuroscience, 3:3-4, 193-207 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2012.674935 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

Implicit and Explicit Memory for Novel Visual Objects in Older and \Bunger Adults

Psychology and Aging Copyright 1992 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1992, Vol. 7, No. 2, 299-308 0882-7974/92/53.00 Implicit and Explicit Memory for Novel Visual Objects in Older and \bunger Adults Daniel L. Schacter Lynn A. Cooper Harvard University Columbia University Michael Valdiserri University of Arizona Two experiments examined effects of aging on implicit and explicit memory for novel visual ob- jects. Implicit memory was assessed with an object decision task in which subjects indicated whether briefly exposed drawings represented structurally possible or impossible objects. Explicit memory was assessed with a yes-no recognition task. On the object decision task, old and young subjects both showed priming for previously studied possible objects and no priming for impossible objects; the magnitude of the priming effect did not differ as a function of age. By contrast, the elderly were impaired on the recognition task. Results suggest that the ability to form and retain structural descriptions of novel objects may be spared in older adults. Explicit memory refers to conscious recollection of previous 1988; Davis et al, 1990; Hultsch, Masson, & Small, 1991). These experiences, as expressed on recall and recognition tests, latter findings are difficult to interpret, however, because they whereas implicit memory refers to facilitations of performance, may well reflect "contamination" of implicit task performance often referred to as priming effects, on tests that do not require by explicit retrieval strategies, strategies that are more benefi- any conscious or intentional retrieval of previous experiences cial to young than to old subjects (cf. Graf, 1990; Howard, 1991; (Graf & Schacter, 1985; Schacter, 1987).