The Neuropsychology of Memory Illusions: False Recall and Recognition in Amnesic Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reducing False Memories Chad S

MacLeod and MacDonald – The Stroop effect and attention Review 17 Dunbar, K.N. and MacLeod, C.M. (1984) A horse race of a different 28 Carter, C.S. et al. (2000) Parsing executive processes: strategic versus color: Stroop interference patterns with transformed words. J. Exp. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 10, 622–639 Sci. U. S. A. 97, 1944–1948 18 Fraisse, P. (1969) Why is naming longer than reading? Acta Psychol. 29 Derbyshire, S.W.G. et al. (1998) Pain and Stroop interference activate 30, 96–103 separate processing modules in anterior cingulate. Exp. Brain Res. 19 Kolers, P.A. (1975) Memorial consequences of automatized encoding. 118, 52–60 J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 1, 689–701 30 Bush, G. et al. (2000) Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior 20 Tzelgov, J. et al. (1992) Controlling Stroop effects by manipulating cingulate cortex. Trends Cognit. Sci. 4, 215–222 expectations for color words. Mem. Cognit. 20, 727–735 31 Corbetta, M. et al. (1991) Selective and divided attention during visual 21 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. (1981) P300 latency: a new metric of discriminations of shape, color, and speed: functional anatomy by information processing. Psychophysiology 18, 207–215 positron emission tomography. J. Neurosci. 11, 2383–2402 22 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. and Kopell, B.S. (1981) The Stroop effect: brain 32 Petersen, S.E. et al. (1988) Positron emission tomographic studies potentials localize the source of interference. Science 214, 938–940 of the cortical anatomy of single-word processing. Nature 23 Bench, C.J. -

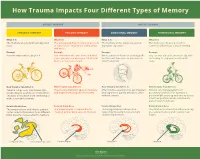

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

False-Memory Stories

Telling Incest: Narratives of Dangerous Remembering from Stein to Sapphire Janice Doane and Devon Hodges http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=10780 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. Chapter 5 The Science of Memory False-Memory Stories False Memory Syndrome Foundation members, largely those who have been accused of child abuse and expert witnesses on their behalf, have compelling reasons to insist that repressed memories of abuse be veri‹ed by clear and con- vincing empirical evidence, precisely the kind of evidence often lacking in incestuous abuse cases.1 While there are cases where a child with venereal dis- ease or a bleeding vagina is admitted to an emergency room and evidence obtained of abuse, signs of molestation may not be at all obvious. Adults have been mistakenly charged with abuse as a result of misreadings of physical evi- dence, resulting, for example, from incorrect assumptions about what “nor- mal” genitals and hymens are supposed to look like (Nathan and Snedeker, 180–81). And children enjoined to silence may long delay reports of abuse, with the result that physical marks of molestation, should they exist, would be healed by the time accusations are made. Without damning physical evidence, charges of incestuous abuse are hard to prove. If the memory wars re›ect deep ambivalence about the declining fortunes of patriarchal authority, they are sus- tained by problems with collecting incontrovertible evidence of sexual abuse, whether to vindicate accusers or the accused. What is debated are less tangible archives of the past. As we have seen, proponents of recovered memory focus on psychological processes, such as repression and dissociation, that long impede the recollection of sexual abuse. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

Memory Search

Memory Search Michael J. Kahana Department of Psychology University of Pennsylvania Draft: Do not quote Abstract Much has been learned about the dynamics of memory search in the last two decades, primarily through the lens of the free recall task. Here I review the major empirical findings obtained using this memory-search paradigm. I also discuss how these findings have been used to advance theories of memory search. Specific topics covered include serial-position effects, recall dynam- ics and organizational processes, false recall, repetition and spacing effects, inter-response times, and individual differences. At our dinner table each evening my wife and I ask our children to tell us what hap- pened to them at school that day; our older ones sometimes ask us to tell them stories from our day at work. Answering these questions requires that we each search our memories for the day's events, and evaluate each memory's interest value for the dinner table conversa- tion. Our search must target those memories that belong to a particular context, usually defined by the time and place in which the event occurred. In the psychological laboratory, this task is referred to as free recall, and is studied by first having subjects experience a series of items (the study list), Then, either immediately or after some delay, subjects attempt to recall as many items as they can remember irrespective of the items' order of presentation. Unlike other memory tasks, free recall does not provide a specific retrieval cue for each target item. Typically, items are common words presented one at a time on a computer monitor. -

{Download PDF} False Memories

FALSE MEMORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Isaku Natsume | 202 pages | 01 Aug 2013 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421558561 | English | San Francisco, CA, United States False Memories PDF Book We may also include misinformation we encountered after the event. Recent research suggests negative emotions lead to more false memories than positive or neutral emotions. Archived from the original on 12 March Psychological phenomenon. Audio help More spoken articles. You say yes, then quickly correct yourself to say it was black. The researchers then asked the participants if they had seen any broken glass, knowing that there was no broken glass in the video. Marsh , Dept. Upon asking a respondent a question that provides a presupposition, the respondent will provide a recall in accordance with the presupposition if accepted to exist in the first place. American Psychologist. Instead, fuzzy trace theory puts forward the idea that there are two types of memory: verbatim and gist. This is sometimes called the Mandela effect. New York: Oxford University Press; This is what a lot of people think happened in the Netflix series "Making a Murderer," for instance. The data was scored so that if a child made one false affirmation during the interview, the child was classified as inaccurate. In , Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer conducted a study [5] to investigate the effects of language on the development of false memory. Cognitive Psychology, 22, Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description is different from Wikidata Use dmy dates from June All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from February CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown Spoken articles Articles with hAudio microformats. -

THE ROLE of WORKING MEMORY CAPACITY in FALSE MEMORY a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Psychology California

THE ROLE OF WORKING MEMORY CAPACITY IN FALSE MEMORY A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Psychology California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Psychology by Lilian Edith Cabrera SUMMER 2016 © 2016 Lilian Edith Cabrera ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE ROLE OF WORKING MEMORY CAPACITY IN FALSE MEMORY A Thesis by Lilian Edith Cabrera Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Jianjian Qin, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Lawrence S. Meyers, Ph.D. __________________________________, Third Reader Jeffrey Calton, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Lilian Edith Cabrera I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Lisa M. Bohon, Ph.D. Date Department of Psychology iv Abstract of THE ROLE OF WORKING MEMORY CAPACITY IN FALSE MEMORY by Lilian Edith Cabrera The present study examined the effect of working memory capacity in false memory elicited by the DRM paradigm in two experiments (Experiment 1: N = 31, 80.6% female, age M = 21.29 years, SD = 4.26; Experiment 2: N = 29, 72.4% female, age M = 20.28 years, SD = 3.02). A concurrent digit load task was introduced to reduce available working memory capacity for the DRM task. The results of Experiment 1 revealed that false recall of critical lures was marginally higher when participants had a concurrent digit load task. While the initial increase in the digit load increased false recognition of critical lures, a further increase in the digit load reduced false recognition. -

Source Misattributions May Increase the Accuracy of Source Judgments

Memory & Cognition 2007, 35 (5), 1024-1033 Source misattributions may increase the accuracy of source judgments KEITH B. LYLE University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky AND MARCIA K. JOHNSON Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Misattribution of remembered information from one source to another is commonly associated with false memories, but we demonstrate that it also may underlie memories that accord with past events. Participants imagined drawings of objects in four different locations. For each, a drawing of a similarly shaped object was seen in the same location, a different location, or not seen. When tested on memory for objects’ origin (seen/ imagined) and location, more false “seen” responses, but also more correct location responses, were given to imagined objects if a similar object had been seen, versus not seen, in the same location. We argue that misat- tribution of feature information (e.g., shape, location) from seen objects to similar imagined ones increased false memories of seeing objects but also increased correct location memories, provided the misattributed location matched the imagined objects’ location. Thus, consistent with the source-monitoring framework, imperfect source-attribution processes underlie false and true memories. The idea that remembered information from one source Geraci & Franklin, 2004; Henkel & Franklin, 1998). This may be mistakenly attributed to a different source (i.e., increase in false memory for having seen the drawings is source misattribution) has proven useful in explaining thought to be due to the misattribution of perceived fea- a variety of false memory phenomena (Johnson, Hash- ture information from seen objects to similar imagined troudi, & Lindsay, 1993; Mitchell & Johnson, 2000). -

Inquiry Into the Practice of Recovered Memory Therapy

INQUIRY INTO THE PRACTICE OF RECOVERED MEMORY THERAPY September 2005 Report by the Health Services Commissioner to the Minister for Health, the Hon. Bronwyn Pike MP under Section 9(1)(m) of the Health Services (Conciliation and Review) Act 1987 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 DEFINITIONS...............................................................................................................................4 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................7 3 RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................................................17 4 BACKGROUND TO THE INQUIRY.....................................................................................18 4.1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................18 4.2 Terms of Reference.............................................................................................................19 4.3 The Inquiry Team ................................................................................................................20 4.4 Methodology...........................................................................................................................20 4.4.1 Literature review ..........................................................................................................20 4.4.2 Legislative review ........................................................................................................20 -

TRAUMATIC AMNESIA a Dissociative Survival Mechanism

TRAUMATIC AMNESIA a dissociative survival mechanism Dr. Muriel Salmona, psychiatrist, Paris, January 19, 2018 I - Presentation Complete or fragmented traumatic amnesia is a common memory disorder found in victims of violence. Numerous clinical studies have described this well- known phenomenon since the beginning of the twentieth century, when the first systematic studies explored amnesia among traumatized combat soldiers, and later among victims of sexual violence. Studies found almost 40 % complete amnesia among these participants, and 60% partial amnesia when childhood sexual abuse was concerned (Brière 1993, Williams 1994, IVSEA 2015). These amnesias are psychotraumatic consequences of violence. They are neuro- psychological survival mechanisms based on dissociation (Van der Kolk, 1995, 2001). Since 2015, dissociative traumatic amnesias have been recognized as a defining criterium for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (DSM-5, 2015). They can last several decades and lead to amnesia for entire sections of childhood, with almost no retrievable memory, which results in a painful impression of having no past, nor landmarks. When amnesia fades away, traumatic memories most often return brutally, invasively, as uncontrolled, unintegrated, fragmented traumatic memories (flashbacks, nightmares) and trigger re-experiences of violence with identitical distress and sensations, and a vividness as if the trauma was happening all over again. Care professionals should be better acquainted with these phenomena in order to improve how they care for the victims, by treating such reminiscences without confusing them with hallucinations, identifying violence, and its psychotraumatic consequences for the victims. Similarly, justice professionals, when faced with sexual violence complaints after recovered memories, should be more aware of the reality of such frequent memory disorder. -

Rethinking Trauma

How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Daniel Siegel, MD - Main Session - pg. 1 Rethinking Trauma How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma the Main Session with Daniel Siegel, MD and Ruth Buczynski, PhD National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Daniel Siegel, MD - Main Session - pg. 2 Rethinking Trauma: Daniel Siegel, MD How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Table of Contents (click to go to a page) How To Define What Happens in the Brain During Trauma ................................... 3 The Optimally Functioning vs. Traumatized Brain as Defined by FACES ................. 4 How Age Affects the Impact of Trauma on the Brain .............................................. 7 Trauma Leads to the Chemical Release of Cortisol and Adrenaline ....................... 8 How Trauma Impairs the Brain’s Memory Systems ............................................... 10 Why the Brain’s Developmental Period Is Crucial to Working with Trauma ............ 11 The Layers of Memory and Encoding Implicit Memory .......................................... 13 The Retrieval of Implicit Memory and the Experience of Flashback ...................... 15 Putting the Science into Clinical Practice ............................................................... 17 What Happens in the Brain during Dissociation? ................................................... 18