CHILDREN's MEMORY, TRAUMATIC MEMORIES and the CHILD WITNESS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissociation Related to Subjective Memory Fragmentation and Intrusions but Not to Objective Memory Disturbances

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 36 (2005) 43–59 www.elsevier.com/locate/jbtep Dissociation related to subjective memory fragmentation and intrusions but not to objective memory disturbances Merel Kindta,Ã, Marcel Van den Houtb, Nicole Buckb aDepartment of Clinical Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Roetersstraat 15, 1018 WB Amsterdam, The Netherlands bDepartment of Medical, Clinical and Experimental Psychology, Maastricht University, The Netherlands Abstract The present study was a replication of Kindt and Van den Hout (Behaviour Research and Therapy 41 (2003) 167) with several methodological adaptations. Two experiments were designed to test whether state dissociation is related to objective memory disturbances, or whether dissociation is confined to the realm of subjective experience. High trait dissociative participants (Nexp:1 ¼ 25; Nexp:2 ¼ 25) and low trait dissociative participants (Nexp:1 ¼ 25; Nexp:2 ¼ 25) were selected from normal samples (Nexp:1 ¼ 372; Nexp:2 ¼ 341) on basis of scores on the Dissociative Experience Scale (DES). Participants watched an extremely aversive film, after which state dissociation was measured by the Peri-traumatic Dissociative Experience Questionnaire (PDEQ). Memory disturbances were assessed 4h later (Exp. 1) or 1 week later (Exp. 2). Objective memory disturbances were assessed by a sequential memory task, items tapping perceptual representations (Exp. 1), or an open question with respect to the remembrance of the film (Exp. 2). Subjective memory disturbances were measured by means of visual analogue scales assessing fragmentation and intrusions. The two experiments provided a fairly exact replication of an earlier experiment (Behaviour Research and Therapy 41 (2003) ÃCorresponding author. Fax: +31 20 6391369 E-mail address: [email protected] (M. -

How Big Is Human Memory, Or on Being Just Useful Enough

Downloaded from learnmem.cshlp.org on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW Yadin Dudai How Big Is Human Memory, Department of Neur0bi010gy or On Being Just Useful Enough The Weizmann Institute of Science Reh0v0t 76100 Israel We are, in many respects, what we remember. But how much do we do? So far, science has provided only a very partial answer to this riddle. The magical number seven, plus or minus two, seems to constrain the capacity of our immediate memory (Miller 1956). But surely its constraints dissipate when memories settle in long-term stores. Yet how big are these stores? If we combine all of our factual knowledge and personal reminiscence, childhood scenes and memories of the past day, intimate experiences and professional expertisemhow many items are there, that, combined together, mold us into unique individuals? The answer is not simple, and neither is the question. For example, what is an item in long-term memory? And how can we measure it, being sure that we unveil memory capacity and not merely the occasional ability to tap it? Such theoretical and practical difficulties, no doubt, have contributed to the fact that the capacity of human memory is still an enigma. Yet, despite the inherent and undeniable complexities, the issue deserves to be retrieved, once in a while, from the oblivions of the collective memory of the scientific community. (For a selection of earlier discussions of the size of human long-term memory, see Galton 1879; Landauer 1986; Crovitz et al. 1991.) Folk Psychology and When confronted with the issue, many tend to provide an intuitive Early Views estimate of the size of their memory, based either on belief or introspection or both. -

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain or Where did I put those keys? CHARLES J. VELLA, PHD 2018 Proust & his Madeleine: Olfaction and Memory "I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touch my palate than a shudder ran trough me and I sopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure invaded my senses..... And suddenly the memory revealed itself. “ Marcel Proust À la recherche du temps perdu (known in English as: In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past): 7 Volumes, 4000 pp. Proustian Effect: fragrances elicit more emotional and evocative memories than other memory cues Study: Proustian Products are Preferred: The Relationship Between Odor-Evoked Memory and Product Evaluation: Lotions preferred if they evoke personal emotional memories Memory Determines your sense of self Determines your ability to plan for future Enables you to remember your past Learning: Ability to learn new things Learning is a restless, piecemeal, subconscious, sneaky process that occurs all the time, when we are awake and when we are asleep. Older Explanation of Memory ATTENTION PROCESSING ENCODING STORAGE RETRIEVAL William James: "My experience is what I agree to attend to.“ Tip #1: There is no memory without first paying attention. Multiple Historical Metaphors for Memory based on then current technology •In Plato’s Theaetetus, metaphor of a stamp on wax • 1904 the German scholar Richard Semon: the engram. • Photograph • Tape recorder • Mirror • Hard drive • Neural network False Assumption: perfect image or recording, lasts forever Purpose of Memory We think of memory as a record of our past experience. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

Memory Reconsolidation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Current Biology Vol 23 No 17 R746 emerged from the pattern of amnesia consequence of this dynamic process Memory collectively caused by all these is that established memories, which reconsolidation different types of interventions. have reached a level of stability, can be Memory consolidation appeared to bidirectionally modulated and modified: be a complex and quite prolonged they can be weakened, disrupted Cristina M. Alberini1 process, during which different types or enhanced, and be associated and Joseph E. LeDoux1,2 of amnestic manipulation were shown to parallel memory traces. These to disrupt different mechanisms in the possibilities for trace strengthening The formation, storage and use of series of changes occurring throughout or weakening, and also for qualitative memories is critical for normal adaptive the consolidation process. The initial modifications via retrieval and functioning, including the execution phase of consolidation is known to reconsolidation, have important of goal-directed behavior, thinking, require a number of regulated steps behavioral and clinical implications. problem solving and decision-making, of post-translational, translational and They offer opportunities for finding and is at the center of a variety of gene expression mechanisms, and strategies that could change learning cognitive, addictive, mood, anxiety, blockade of any of these can impede and memory to make it more efficient and developmental disorders. Memory the entire consolidation process. and adaptive, to prevent or rescue also significantly contributes to the A century of studies on memory memory impairments, and to help shaping of human personality and consolidation proposed that, despite treat diseases linked to abnormally character, and to social interactions. -

Early Childhood Memory and Attention As Predictors of Academic Growth Trajectories

Running head: MEMORY, ATTENTION AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT 1 Early Childhood Memory and Attention as Predictors of Academic Growth Trajectories Deborah Stipek and Rachel Valentino Stanford University Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Deborah Stipek, Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305. Email: [email protected] Running head: MEMORY, ATTENTION AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT 2 Abstract Longitudinal data from the children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) were used to assess how well measures of short-term and working memory and attention in early childhood predicted longitudinal growth trajectories in mathematics and reading comprehension. Analyses also examined whether changes in memory and attention were more strongly predictive of changes in academic skills in early childhood than in later childhood. All predictors were significantly associated with academic achievement and years of schooling attained, although the latter was at least partially mediated by predictors’ effect on academic achievement in adolescence. The relationship of working memory and attention with academic outcomes was also found to be strong and positive in early childhood, but non-significant or small and negative in later years. The study results provide support for a “fade-out” hypothesis, which suggests that underlying cognitive capacities predict learning in the early elementary grades, but the relationship fades by late elementary school. These findings suggest that whereas efforts to develop attention and memory may improve academic achievement in the early grades, in the later grades interventions that focus directly on subject matter learning are more likely to improve achievement. Running head: MEMORY, ATTENTION AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT 3 Early Childhood Memory and Attention as Predictors of Academic Growth Trajectories Success in school requires many skills. -

Empirical Evidence Supporting Neural Contributions to Episodic Memory Development In

Empirical Evidence Supporting Neural Contributions to Episodic Memory Development in Early Childhood: Implications for Childhood Amnesia Tracy Riggins Kelsey L. Canada Morgan Botdorf University of Maryland, College Park Key words: childhood amnesia, memory development, brain development, hippocampus Abstract Memories for events that happen early in life are fragile—they are forgotten more quickly than expected based on typical adult rates of forgetting. Although numerous factors contribute to this phenomenon, data show one major source of change is the protracted development of neural structures related to memory. Recent empirical studies in early childhood reveal that the development of specific subdivisions of the hippocampus (i.e., the dentate gyrus) are related directly to variations in memory. Yet the hippocampus is only one region within a larger network supporting memory. Data from young children have also shown that activation of cortical regions during memory tasks and the functional connectivity between the hippocampus and cortex relate to memory during this period. Taken together, these results suggest that protracted neural development of the hippocampus, cortex, and connections between these regions contribute to the fragility of memories early in life and may ultimately contribute to childhood amnesia. You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all... Our memory is our coherence, our reason, our feeling, even our action. Without it we are nothing. (Buñuel (1984, p.17). How Does the Ability to Remember Change Across Development? The ability to remember details from events in life is critical for functioning and a personal sense of self. -

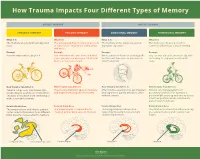

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: the Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories

Psychology and Aging Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2002, Vol. 17, No. 4, 636–652 0882-7974/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.636 Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: The Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories Dorthe Berntsen David C. Rubin University of Aarhus Duke University A sample of 1,241 respondents between 20 and 93 years old were asked their age in their happiest, saddest, most traumatic, most important memory, and most recent involuntary memory. For older respondents, there was a clear bump in the 20s for the most important and happiest memories. In contrast, saddest and most traumatic memories showed a monotonically decreasing retention function. Happy involuntary memories were over twice as common as unhappy ones, and only happy involuntary memories showed a bump in the 20s. Life scripts favoring positive events in young adulthood can account for the findings. Standard accounts of the bump need to be modified, for example, by repression or reduced rehearsal of negative events due to life change or social censure. Many studies have examined the distribution of autobiographi- (1885/1964) drew attention to conscious memories that arise un- cal memories across the life span. No studies have examined intendedly and treated them as one of three distinct classes of whether this distribution is different for different classes of emo- memory, but did not study them himself. In his well-known tional memories. Here, we compare the event ages of people’s textbook, Miller (1962/1974) opened his chapter on memory by most important, happiest, saddest, and most traumatic memories quoting Marcel Proust’s description of how the taste of a Made- and most recent involuntary memory to explore whether different leine cookie unintendedly brought to his mind a long-forgotten kinds of emotional memories follow similar patterns of retention. -

Culture Effects on Adults' Earliest Childhood Recollection and Self-Description: Implications for the Relation Between Memory and the Self

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2001, Vol. 81, No. 2, 220-233 0022-3514/01/S5.00 DOI: 10.1037//OO22-3514.81.2.220 Culture Effects on Adults' Earliest Childhood Recollection and Self-Description: Implications for the Relation Between Memory and the Self Qi Wang Cornell University American and Chinese college students (N = 256) reported their earliest childhood memory on a memory questionnaire and provided self-descriptions on a shortened 20 Statements Test (M. H. Kuhn & T. S. McPartland, 1954). The average age at earliest memory of Americans was almost 6 months earlier than that of Chinese. Americans reported lengthy, specific, self-focused, and emotionally elaborate memories; they also placed emphasis on individual attributes in describing themselves. Chinese provided brief accounts of childhood memories centering on collective activities, general routines, and emotionally neutral events; they also included a great number of social roles in their self-descriptions. Across the entire sample, individuals who described themselves in more self-focused and positive terms provided more specific and self-focused memories. Findings are discussed in light of the interactive relation between autobiographical memory and cultural self-construal. When asked to think of her earliest childhood memory, a Har- The work of early theorists (e.g., Greenwald, 1980; Kelly, 1955; vard undergraduate wrote down the following episode that hap- Markus, 1977; Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977; Schachtel, 1947) pened when she was about 3 years old: foreshadowed the interface between the self and autobiographical memory. For example, George Kelly (1955) proposed that a per- I remember standing in my aunt's spacious blue bedroom and looking sonal experience must be supported within an existing self- up at the ceiling. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology