How We Learn: Memory & the Brain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

How Big Is Human Memory, Or on Being Just Useful Enough

Downloaded from learnmem.cshlp.org on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW Yadin Dudai How Big Is Human Memory, Department of Neur0bi010gy or On Being Just Useful Enough The Weizmann Institute of Science Reh0v0t 76100 Israel We are, in many respects, what we remember. But how much do we do? So far, science has provided only a very partial answer to this riddle. The magical number seven, plus or minus two, seems to constrain the capacity of our immediate memory (Miller 1956). But surely its constraints dissipate when memories settle in long-term stores. Yet how big are these stores? If we combine all of our factual knowledge and personal reminiscence, childhood scenes and memories of the past day, intimate experiences and professional expertisemhow many items are there, that, combined together, mold us into unique individuals? The answer is not simple, and neither is the question. For example, what is an item in long-term memory? And how can we measure it, being sure that we unveil memory capacity and not merely the occasional ability to tap it? Such theoretical and practical difficulties, no doubt, have contributed to the fact that the capacity of human memory is still an enigma. Yet, despite the inherent and undeniable complexities, the issue deserves to be retrieved, once in a while, from the oblivions of the collective memory of the scientific community. (For a selection of earlier discussions of the size of human long-term memory, see Galton 1879; Landauer 1986; Crovitz et al. 1991.) Folk Psychology and When confronted with the issue, many tend to provide an intuitive Early Views estimate of the size of their memory, based either on belief or introspection or both. -

Empirical Evidence Supporting Neural Contributions to Episodic Memory Development In

Empirical Evidence Supporting Neural Contributions to Episodic Memory Development in Early Childhood: Implications for Childhood Amnesia Tracy Riggins Kelsey L. Canada Morgan Botdorf University of Maryland, College Park Key words: childhood amnesia, memory development, brain development, hippocampus Abstract Memories for events that happen early in life are fragile—they are forgotten more quickly than expected based on typical adult rates of forgetting. Although numerous factors contribute to this phenomenon, data show one major source of change is the protracted development of neural structures related to memory. Recent empirical studies in early childhood reveal that the development of specific subdivisions of the hippocampus (i.e., the dentate gyrus) are related directly to variations in memory. Yet the hippocampus is only one region within a larger network supporting memory. Data from young children have also shown that activation of cortical regions during memory tasks and the functional connectivity between the hippocampus and cortex relate to memory during this period. Taken together, these results suggest that protracted neural development of the hippocampus, cortex, and connections between these regions contribute to the fragility of memories early in life and may ultimately contribute to childhood amnesia. You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all... Our memory is our coherence, our reason, our feeling, even our action. Without it we are nothing. (Buñuel (1984, p.17). How Does the Ability to Remember Change Across Development? The ability to remember details from events in life is critical for functioning and a personal sense of self. -

Hippocampal–Caudate Nucleus Interactions Support Exceptional Memory Performance

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-017-1556-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hippocampal–caudate nucleus interactions support exceptional memory performance Nils C. J. Müller1 · Boris N. Konrad1,2 · Nils Kohn1 · Monica Muñoz-López3 · Michael Czisch2 · Guillén Fernández1 · Martin Dresler1,2 Received: 1 December 2016 / Accepted: 24 October 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Participants of the annual World Memory competitive interaction between hippocampus and caudate Championships regularly demonstrate extraordinary mem- nucleus is often observed in normal memory function, our ory feats, such as memorising the order of 52 playing cards findings suggest that a hippocampal–caudate nucleus in 20 s or 1000 binary digits in 5 min. On a cognitive level, cooperation may enable exceptional memory performance. memory athletes use well-known mnemonic strategies, We speculate that this cooperation reflects an integration of such as the method of loci. However, whether these feats the two memory systems at issue-enabling optimal com- are enabled solely through the use of mnemonic strategies bination of stimulus-response learning and map-based or whether they benefit additionally from optimised neural learning when using mnemonic strategies as for example circuits is still not fully clarified. Investigating 23 leading the method of loci. memory athletes, we found volumes of their right hip- pocampus and caudate nucleus were stronger correlated Keywords Memory athletes · Method of loci · Stimulus with each other compared to matched controls; both these response learning · Cognitive map · Hippocampus · volumes positively correlated with their position in the Caudate nucleus memory sports world ranking. Furthermore, we observed larger volumes of the right anterior hippocampus in ath- letes. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology -

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize Anne Vetter, Daniel Gotz,¨ Sebastian von Mammen Games Engineering, University of Wurzburg,¨ Germany fanne.vetter,[email protected], [email protected] Abstract—There are uncountable things to be remembered, but assistance during comprehension (R6) of the information, e.g. most people were never shown how to memorize effectively. With by means of verbalization, should follow suit. Due to the this paper, the application The Art of Loci (TAoL) is presented, heterogeneity of learners, the applied process and methods to provide the means for efficient and fun learning. In a virtual reality (VR) environment users can express their study material should be individualized (R7) and strike a productive balance visually, either creating dimensional mind maps or experimenting between user’s choices and imposed learning activities (locus with mnemonic strategies, such as mind palaces. We also present of control) (R8). For example, users should be able to control common memorization techniques in light of their underlying the pace of learning. Learning environments should arouse the pedagogical foundations and discuss the respective features of intrinsic motivation of the user (R9). Fostering an awareness TAoL in comparison with similar software applications. of the learner’s cognition and thus reflection on their learning I. INTRODUCTION process and strategies is also beneficial (metacognition) (R10). Further, a constructivist learning approach can be realized by Before writing was common, information could only be the means to create artefacts such as representations, symbols preserved by memorization. Major ancient literature like The or cues (R11). Finally, cooperative and collaborative learning Iliad and The Odyssey were memorized, passed on through environments can benefit the learning process (R12). -

Chapter 16 Improving Your Memory + 2 Tips for Selecting Passwords

+ Chapter 16 Improving Your Memory + 2 Tips for Selecting Passwords Use a transformation of some memorable cue involving a mix of letters and symbols Keep a record of all passwords in a place to which only you have access (e.g. a safe deposit box) It is easier to recall the location of a hidden object when the location is likely than when it is unexpected + 3 Popular Mnemonic Aids Harris (1980) surveyed housewives and students on their mnemonic use: Both groups used largely similar techniques; however, Students were more likely to write on their hands Housewives were more likely to write on calendars External aids (e.g. diaries, calendars, lists, and timers) were especially popular …Today we have laptops, PDAs, and mobile telephones Very few internal mnemonics were reported These are especially useful in situations that ban external aids + 4 Memory Experts Shereshevskii The Mind of a Mnemonist by Luria A Russian with an amazing memory A former journalist who never took notes but could repeat back quotes verbatim Had seemingly limitless memory for: Digits (100+) Nonsense syllables Foreign-language poetry Complex figures Complex scientific formulae His memory relied heavily on imagery and synesthesia: The tendency for one sense modality to evoke another His apparent inability to forget, and his synesthesia, caused great complications and struggle for him + Wilding and Valentine (1994) 5 Naturals vs. Strategists Naturals Strategists Innately gifted Highly practiced in certain mnemonic techniques Possess a close relative who exhibits a comparable level of memory ability Tested both kinds of mnemonists at the World Memory Championships on two types of tasks: Strategic Tasks e.g. -

Ernest Schachtel, on Memory and Infantile Amnesia

128 politics On 3Mem^ry and ChMdh^^ad A^wnnesia Ernest €r. Schachtel^ REEK mythology celebrates Mnemosyne, the goddess Today the masses have internalized the ancient fear and of memory, as the mother of all art. She bore the prohibition of this alluring song and, in their contempt for G nine muses to Zeus.^ Centuries after the origin of it, express and repress both their longing for and their fear this myth Plato banned poetry, the child of memory, from of the unknown vistas to which it might open the doors. his ideal state as being idle and seductive. While lawmak The profound fascination of memory of past experience ers, generals, and inventors were useful for the common and the double aspect of this fascination—^its irresistible good, the fact that Homer was nothing but a wandering lure into the past with its promise of happiness and pleas minstrel without a home and without a following proved ure, and its threat to the kind of activity, planning, and how useless he was.^ In the Odyssey the voices of the purposeful thought and behavior encouraged by modern Sirens tempt Ulysses. western civilization—^have attracted the thought of two men in recent times who have made the most significant modern For never yet hath any man rowed past This isle in his black ship, till he hath heard contribution to the ancient questions posed by the Greek The honeyed music of our lips, and goes myth: Sigmund Freud and Marcel Proust. His way delighted and a wiser man. Both are aware of the antagonism inherent in memory, For see, we know the whole tale of the travail That Greeks and Trojans suffered in wide Troy-land the conflict between reviving the past and actively partici By Heaven's behest; yea, and all things we know pating in the present life of society. -

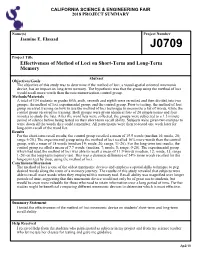

Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR 2018 PROJECT SUMMARY Name(s) Project Number Jasmine E. Elasaad J0709 Project Title Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory Abstract Objectives/Goals The objective of this study was to determine if the method of loci, a visual-spatial oriented mnemonic device, has an impact on long-term memory. The hypothesis was that the group using the method of loci would recall more words than the rote memorization control group. Methods/Materials A total of 134 students in grades fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth were recruited and then divided into two groups: the method of loci experimental group; and the control group. Prior to testing, the method of loci group received training on how to use the method of loci technique to memorize a list of words, while the control group received no training. Both groups were given identical lists of 20 simple nouns and four minutes to study the lists. After the word lists were collected, the groups were subjected to a 1.5 minute period of silence before being tested on their short-term recall ability. Subjects were given two minutes to write down all the words they could remember. All participants were then re-tested one week later for long-term recall of the word list. Results For the short-term recall results, the control group recalled a mean of 15.5 words (median 16; mode, 20; range 6-20.) The experimental group using the method of loci recalled 16% more words than the control group, with a mean of 18 words (median 19; mode, 20; range, 11-20). -

The Method of Loci in Virtual Reality: Explicit Binding of Objects to Spatial Contexts Enhances Subsequent Memory Recall

Journal of Cognitive Enhancement https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-019-00141-8 ORIGINAL RESEARCH The Method of Loci in Virtual Reality: Explicit Binding of Objects to Spatial Contexts Enhances Subsequent Memory Recall Nicco Reggente1 & Joey K. Y. Essoe1 & Hera Younji Baek1 & Jesse Rissman1,2 Received: 7 January 2019 /Accepted: 7 June 2019 # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract The method of loci (MoL) is a well-known mnemonic technique in which visuospatial spatial environments are used to scaffold the memorization of non-spatial information. We developed a novel virtual reality-based implementation of the MoL in which participants used three unique virtual environments to serve as their “memory palaces.” In each world, participants were presented with a sequence of 15 3D objects that appeared in front of their avatar for 20 s each. The experimental group (N = 30) was given the ability to click on each object to lock it in place, whereas the control group (N = 30) was not afforded this functionality. We found that despite matched engagement, exposure duration, and instructions emphasizing the efficacy of the mnemonic across groups, participants in the experimental group recalled 28% more objects. We also observed a strong relation- ship between spatial memory for objects and landmarks in the environment and verbal recall strength. These results provide evidence for spatially mediated processes underlying the effectiveness of the MoL and contribute to theoretical models of memory that emphasize spatial encoding as the primary currency of mnemonic function. Keywords Memory enhancement . Method of loci . Virtual reality Introduction the MoL is a complicated, time-consuming mnemonic to imple- ment, but in fact, it is rather straightforward. -

Can Cognitive Neuroscience Illuminate the Nature of Traumatic Childhood Memories? Daniel L Schacterl, Wilma Koutstaal and Kenneth a Norman

207 Can cognitive neuroscience illuminate the nature of traumatic childhood memories? Daniel L Schacterl, Wilma Koutstaal and Kenneth A Norman Recent findings from cognitive neuroscience and cognitive distortion? Can traumatic events be forgotten, and if so, psychology may help explain why recovered memories of can they be later recovered? We first consider evidence trauma are sometimes illusory. In particular, the notion of that pertains to claims of recovered memories of trauma. defective source monitoring has been used to explain a wide We then consider the relevant memory phenomena in the range of recently established memory distortions and illusions. context of concepts and findings from the contemporary Conversely, the results of a number of studies may potentially cognitive neuroscience of memory. be relevant to forgetting and recovery of accurate memories, including studies demonstrating reduced hippocampal volume The recovered memories debate: what do we in survivors of sexual abuse, and recovery from functional and know? organic retrograde amnesia. Other recent findings of interest The controversy over recovered memories is a complex include the possibility that state-dependent memory could be affair that involves several intertwined psychological and induced by stress-related hormones, new pharmacological social issues (for elaboration of this point, see [8-131). models of dissociative states, and evidence for ‘repression’ in Here, we consider four critical questions. First, can patients with right parietal brain damage. memories -

Method-Of-Loci As a Mnemonic Device to Facilitate Access to Self-Affirming Personal Memories for Individuals with Depression

Brief Empirical Report Clinical Psychological Science 1(2) 156 –162 Method-of-Loci as a Mnemonic Device to © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Facilitate Access to Self-Affirming Personal DOI: 10.1177/2167702612468111 Memories for Individuals With Depression http://cpx.sagepub.com Tim Dalgleish, Lauren Navrady, Elinor Bird, Emma Hill, Barnaby D. Dunn, and Ann-Marie Golden Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, UK Abstract Depression impairs the ability to retrieve positive, self-affirming autobiographical memories. To counteract this difficulty, we trained individuals with depression, either in episode or remission, to construct an accessible mental repository for a preselected set of positive, self-affirming memories using an ancient mnemonic technique—the method-of-loci (MoL). Participants in a comparison condition underwent a similar training protocol where they chunked the memories into meaningful sets and rehearsed them (rehearsal). Both protocols enhanced memory recollection to near ceiling levels after 1 week of training. However, on a surprise follow-up recall test a further week later, recollection was maintained only in the MoL condition, relative to a significant decrease in memories recalled in the rehearsal group. There were no significant performance differences between those currently in episode and those in remission. The results support use of the MoL as a tool to facilitate access to self-affirming memories in those with depression. Keywords depression, autobiographical memory, method-of-loci, cognitive training Received 7/27/2012; Revision accepted 9/19/2012 The recollection of autobiographical memories of self-affirming, events that can act in the service of mood repair (Williams positive experiences in the day-to-day has been identified as a et al., 2007).