Moonwalking with Einstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

20 Memory Techniques

20 Memory Techniques Experiment 1,viththese techniques to develop a.flexible, custom-made memm}" system that fits your stJ:fe qf learning the content <ifyour courses and the skills <~/'your,sport. 17w 20 techniques are divided intnfour categories, each 1-vhichrepresents a general principlefiJr improving mem.ory. Organize it 1. Be selective. To a large degree, the art of memory is the a,t of selecting what to remember in the first place. As you dig into your textbooks, playbooks. and notes, make choices about what is most important to learn. Imagine that you are going to create a test on the material and consider the questions you would ask. When reading, look for chapter previews, summaries, and review questions. Pay attention to anything printed in bold type. A !so notice visual elements, such as charts, graphs, and illustrations. All of these are clues pointing to what's important. During lectures, notice what the instructor emphasizes. During practice, focus on what your coach requires you to repeat. Anything that presented visually-on the board, on overheads, or with slides-is also key. 2. Make it meaningful. One way to create meaning is to learn from the general to the specific. Before tackling the details, get the big picture. Before you begin your next reading assignment, for example, skim it lo locate the main idea. If you're ever lost, step back and recall that idea. The details might make more sense. You can also organize any list of items-even random ones-in a meaningful way to make them easier to remember. -

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain or Where did I put those keys? CHARLES J. VELLA, PHD 2018 Proust & his Madeleine: Olfaction and Memory "I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touch my palate than a shudder ran trough me and I sopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure invaded my senses..... And suddenly the memory revealed itself. “ Marcel Proust À la recherche du temps perdu (known in English as: In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past): 7 Volumes, 4000 pp. Proustian Effect: fragrances elicit more emotional and evocative memories than other memory cues Study: Proustian Products are Preferred: The Relationship Between Odor-Evoked Memory and Product Evaluation: Lotions preferred if they evoke personal emotional memories Memory Determines your sense of self Determines your ability to plan for future Enables you to remember your past Learning: Ability to learn new things Learning is a restless, piecemeal, subconscious, sneaky process that occurs all the time, when we are awake and when we are asleep. Older Explanation of Memory ATTENTION PROCESSING ENCODING STORAGE RETRIEVAL William James: "My experience is what I agree to attend to.“ Tip #1: There is no memory without first paying attention. Multiple Historical Metaphors for Memory based on then current technology •In Plato’s Theaetetus, metaphor of a stamp on wax • 1904 the German scholar Richard Semon: the engram. • Photograph • Tape recorder • Mirror • Hard drive • Neural network False Assumption: perfect image or recording, lasts forever Purpose of Memory We think of memory as a record of our past experience. -

Hippocampal–Caudate Nucleus Interactions Support Exceptional Memory Performance

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-017-1556-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hippocampal–caudate nucleus interactions support exceptional memory performance Nils C. J. Müller1 · Boris N. Konrad1,2 · Nils Kohn1 · Monica Muñoz-López3 · Michael Czisch2 · Guillén Fernández1 · Martin Dresler1,2 Received: 1 December 2016 / Accepted: 24 October 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Participants of the annual World Memory competitive interaction between hippocampus and caudate Championships regularly demonstrate extraordinary mem- nucleus is often observed in normal memory function, our ory feats, such as memorising the order of 52 playing cards findings suggest that a hippocampal–caudate nucleus in 20 s or 1000 binary digits in 5 min. On a cognitive level, cooperation may enable exceptional memory performance. memory athletes use well-known mnemonic strategies, We speculate that this cooperation reflects an integration of such as the method of loci. However, whether these feats the two memory systems at issue-enabling optimal com- are enabled solely through the use of mnemonic strategies bination of stimulus-response learning and map-based or whether they benefit additionally from optimised neural learning when using mnemonic strategies as for example circuits is still not fully clarified. Investigating 23 leading the method of loci. memory athletes, we found volumes of their right hip- pocampus and caudate nucleus were stronger correlated Keywords Memory athletes · Method of loci · Stimulus with each other compared to matched controls; both these response learning · Cognitive map · Hippocampus · volumes positively correlated with their position in the Caudate nucleus memory sports world ranking. Furthermore, we observed larger volumes of the right anterior hippocampus in ath- letes. -

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize Anne Vetter, Daniel Gotz,¨ Sebastian von Mammen Games Engineering, University of Wurzburg,¨ Germany fanne.vetter,[email protected], [email protected] Abstract—There are uncountable things to be remembered, but assistance during comprehension (R6) of the information, e.g. most people were never shown how to memorize effectively. With by means of verbalization, should follow suit. Due to the this paper, the application The Art of Loci (TAoL) is presented, heterogeneity of learners, the applied process and methods to provide the means for efficient and fun learning. In a virtual reality (VR) environment users can express their study material should be individualized (R7) and strike a productive balance visually, either creating dimensional mind maps or experimenting between user’s choices and imposed learning activities (locus with mnemonic strategies, such as mind palaces. We also present of control) (R8). For example, users should be able to control common memorization techniques in light of their underlying the pace of learning. Learning environments should arouse the pedagogical foundations and discuss the respective features of intrinsic motivation of the user (R9). Fostering an awareness TAoL in comparison with similar software applications. of the learner’s cognition and thus reflection on their learning I. INTRODUCTION process and strategies is also beneficial (metacognition) (R10). Further, a constructivist learning approach can be realized by Before writing was common, information could only be the means to create artefacts such as representations, symbols preserved by memorization. Major ancient literature like The or cues (R11). Finally, cooperative and collaborative learning Iliad and The Odyssey were memorized, passed on through environments can benefit the learning process (R12). -

Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement Or Self-Depletion?

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 05 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00469 Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement or Self-Depletion? Andrea Lavazza* Neuroethics, Centro Universitario Internazionale, Arezzo, Italy Autobiographical memory is fundamental to the process of self-construction. Therefore, the possibility of modifying autobiographical memories, in particular with memory-modulation and memory-erasing, is a very important topic both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the state of the art of some of the most promising areas of memory-modulation and memory-erasing, considering how they can affect the self and the overall balance of the “self and autobiographical memory” system. Indeed, different conceptualizations of the self and of personal identity in relation to autobiographical memory are what makes memory-modulation and memory-erasing more or less desirable. Because of the current limitations (both practical and ethical) to interventions on memory, I can Edited by: only sketch some hypotheses. However, it can be argued that the choice to mitigate Rossella Guerini, painful memories (or edit memories for other reasons) is somehow problematic, from an Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy ethical point of view, according to some of the theories of the self and personal identity Reviewed by: in relation to autobiographical memory, in particular for the so-called narrative theories Tillmann Vierkant, University of Edinburgh, of personal identity, chosen here as the main case of study. Other conceptualizations of United Kingdom the “self and autobiographical memory” system, namely the constructivist theories, do Antonella Marchetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, not have this sort of critical concerns. -

Elaborative Encoding, the Ancient Art of Memory, and the Hippocampus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2013) 36, 589–659 provided by RERO DOC Digital Library doi:10.1017/S0140525X12003135 Such stuff as dreams are made on? Elaborative encoding, the ancient art of memory, and the hippocampus Sue Llewellyn Faculty of Humanities, University of Manchester, Manchester M15 6PB, United Kingdom http://www.humanities.manchester.ac.uk [email protected] Abstract: This article argues that rapid eye movement (REM) dreaming is elaborative encoding for episodic memories. Elaborative encoding in REM can, at least partially, be understood through ancient art of memory (AAOM) principles: visualization, bizarre association, organization, narration, embodiment, and location. These principles render recent memories more distinctive through novel and meaningful association with emotionally salient, remote memories. The AAOM optimizes memory performance, suggesting that its principles may predict aspects of how episodic memory is configured in the brain. Integration and segregation are fundamental organizing principles in the cerebral cortex. Episodic memory networks interconnect profusely within the cortex, creating omnidirectional “landmark” junctions. Memories may be integrated at junctions but segregated along connecting network paths that meet at junctions. Episodic junctions may be instantiated during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep after hippocampal associational function during REM dreams. Hippocampal association involves relating, binding, and integrating episodic memories into a mnemonic compositional whole. This often bizarre, composite image has not been present to the senses; it is not “real” because it hyperassociates several memories. During REM sleep, on the phenomenological level, this composite image is experienced as a dream scene. -

Memory in Mind and Culture

This page intentionally left blank Memory in Mind and Culture This text introduces students, scholars, and interested educated readers to the issues of human memory broadly considered, encompassing individual mem- ory, collective remembering by societies, and the construction of history. The book is organized around several major questions: How do memories construct our past? How do we build shared collective memories? How does memory shape history? This volume presents a special perspective, emphasizing the role of memory processes in the construction of self-identity, of shared cultural norms and concepts, and of historical awareness. Although the results are fairly new and the techniques suitably modern, the vision itself is of course related to the work of such precursors as Frederic Bartlett and Aleksandr Luria, who in very different ways represent the starting point of a serious psychology of human culture. Pascal Boyer is Henry Luce Professor of Individual and Collective Memory, departments of psychology and anthropology, at Washington University in St. Louis. He studied philosophy and anthropology at the universities of Paris and Cambridge, where he did his graduate work with Professor Jack Goody, on memory constraints on the transmission of oral literature. He has done anthro- pological fieldwork in Cameroon on the transmission of the Fang oral epics and on Fang traditional religion. Since then, he has worked mostly on the experi- mental study of cognitive capacities underlying cultural transmission. After teaching in Cambridge, San Diego, Lyon, and Santa Barbara, Boyer moved to his present position at the departments of anthropology and psychology at Washington University, St. Louis. James V. -

Chapter 16 Improving Your Memory + 2 Tips for Selecting Passwords

+ Chapter 16 Improving Your Memory + 2 Tips for Selecting Passwords Use a transformation of some memorable cue involving a mix of letters and symbols Keep a record of all passwords in a place to which only you have access (e.g. a safe deposit box) It is easier to recall the location of a hidden object when the location is likely than when it is unexpected + 3 Popular Mnemonic Aids Harris (1980) surveyed housewives and students on their mnemonic use: Both groups used largely similar techniques; however, Students were more likely to write on their hands Housewives were more likely to write on calendars External aids (e.g. diaries, calendars, lists, and timers) were especially popular …Today we have laptops, PDAs, and mobile telephones Very few internal mnemonics were reported These are especially useful in situations that ban external aids + 4 Memory Experts Shereshevskii The Mind of a Mnemonist by Luria A Russian with an amazing memory A former journalist who never took notes but could repeat back quotes verbatim Had seemingly limitless memory for: Digits (100+) Nonsense syllables Foreign-language poetry Complex figures Complex scientific formulae His memory relied heavily on imagery and synesthesia: The tendency for one sense modality to evoke another His apparent inability to forget, and his synesthesia, caused great complications and struggle for him + Wilding and Valentine (1994) 5 Naturals vs. Strategists Naturals Strategists Innately gifted Highly practiced in certain mnemonic techniques Possess a close relative who exhibits a comparable level of memory ability Tested both kinds of mnemonists at the World Memory Championships on two types of tasks: Strategic Tasks e.g. -

VIVEKANANDA and the ART of MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1

VIVEKANANDA AND THE ART OF MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1 1. Episodes from Vivekananda’s life 2. Episodes from Ramakrishna’s life 3. Their memory power compared by Swami Saradananda 4. Other srutidharas from the past 5. The ancient art of memory 6. The laws of memory 7. The role of memory in daily life Episodes from Vivekananda’s life The human problem is one of memory. We have forgotten our divine nature. All the great teachers of the past have declared that the revival of the memory of our divinity is the paramount goal. Memory is a faculty and as such, it is neither good nor bad. Every action that we do, every thought that we think, leaves an indelible trail of memory. Whether we remember or not, the contents are recorded and affect our daily life. Therefore, an awareness of this faculty and its method of operation is vital for healthy existence. Properly employed, it leads us to enlightenment; abused or misused, it can torment us. So we must learn to use it properly, to strengthen it for our own improvement. In studying the life of Vivekananda, we come across many phenomenal examples of his amazing faculty of memory. In ‘Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda,’ Haripada Mitra relates the following story: One day, in the course of a talk, Swamiji quoted verbatim some two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. I wondered at this, not understanding how a sanyasin could get by heart so much from a secular book. I thought that he must have read it quite a number of times before he took orders. -

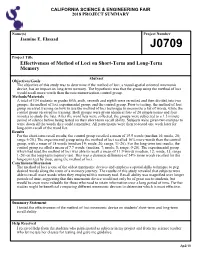

Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR 2018 PROJECT SUMMARY Name(s) Project Number Jasmine E. Elasaad J0709 Project Title Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory Abstract Objectives/Goals The objective of this study was to determine if the method of loci, a visual-spatial oriented mnemonic device, has an impact on long-term memory. The hypothesis was that the group using the method of loci would recall more words than the rote memorization control group. Methods/Materials A total of 134 students in grades fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth were recruited and then divided into two groups: the method of loci experimental group; and the control group. Prior to testing, the method of loci group received training on how to use the method of loci technique to memorize a list of words, while the control group received no training. Both groups were given identical lists of 20 simple nouns and four minutes to study the lists. After the word lists were collected, the groups were subjected to a 1.5 minute period of silence before being tested on their short-term recall ability. Subjects were given two minutes to write down all the words they could remember. All participants were then re-tested one week later for long-term recall of the word list. Results For the short-term recall results, the control group recalled a mean of 15.5 words (median 16; mode, 20; range 6-20.) The experimental group using the method of loci recalled 16% more words than the control group, with a mean of 18 words (median 19; mode, 20; range, 11-20). -

The Method of Loci in Virtual Reality: Explicit Binding of Objects to Spatial Contexts Enhances Subsequent Memory Recall

Journal of Cognitive Enhancement https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-019-00141-8 ORIGINAL RESEARCH The Method of Loci in Virtual Reality: Explicit Binding of Objects to Spatial Contexts Enhances Subsequent Memory Recall Nicco Reggente1 & Joey K. Y. Essoe1 & Hera Younji Baek1 & Jesse Rissman1,2 Received: 7 January 2019 /Accepted: 7 June 2019 # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract The method of loci (MoL) is a well-known mnemonic technique in which visuospatial spatial environments are used to scaffold the memorization of non-spatial information. We developed a novel virtual reality-based implementation of the MoL in which participants used three unique virtual environments to serve as their “memory palaces.” In each world, participants were presented with a sequence of 15 3D objects that appeared in front of their avatar for 20 s each. The experimental group (N = 30) was given the ability to click on each object to lock it in place, whereas the control group (N = 30) was not afforded this functionality. We found that despite matched engagement, exposure duration, and instructions emphasizing the efficacy of the mnemonic across groups, participants in the experimental group recalled 28% more objects. We also observed a strong relation- ship between spatial memory for objects and landmarks in the environment and verbal recall strength. These results provide evidence for spatially mediated processes underlying the effectiveness of the MoL and contribute to theoretical models of memory that emphasize spatial encoding as the primary currency of mnemonic function. Keywords Memory enhancement . Method of loci . Virtual reality Introduction the MoL is a complicated, time-consuming mnemonic to imple- ment, but in fact, it is rather straightforward.