Working Memory Training: Assessing the Efficiency of Mnemonic Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain or Where did I put those keys? CHARLES J. VELLA, PHD 2018 Proust & his Madeleine: Olfaction and Memory "I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touch my palate than a shudder ran trough me and I sopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure invaded my senses..... And suddenly the memory revealed itself. “ Marcel Proust À la recherche du temps perdu (known in English as: In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past): 7 Volumes, 4000 pp. Proustian Effect: fragrances elicit more emotional and evocative memories than other memory cues Study: Proustian Products are Preferred: The Relationship Between Odor-Evoked Memory and Product Evaluation: Lotions preferred if they evoke personal emotional memories Memory Determines your sense of self Determines your ability to plan for future Enables you to remember your past Learning: Ability to learn new things Learning is a restless, piecemeal, subconscious, sneaky process that occurs all the time, when we are awake and when we are asleep. Older Explanation of Memory ATTENTION PROCESSING ENCODING STORAGE RETRIEVAL William James: "My experience is what I agree to attend to.“ Tip #1: There is no memory without first paying attention. Multiple Historical Metaphors for Memory based on then current technology •In Plato’s Theaetetus, metaphor of a stamp on wax • 1904 the German scholar Richard Semon: the engram. • Photograph • Tape recorder • Mirror • Hard drive • Neural network False Assumption: perfect image or recording, lasts forever Purpose of Memory We think of memory as a record of our past experience. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Handbook of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky, Robert A. Bjork Evolution of Metacognition Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 Janet Metcalfe Published online on: 28 May 2008 How to cite :- Janet Metcalfe. 28 May 2008, Evolution of Metacognition from: Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Evolution of Metacognition Janet Metcalfe Introduction The importance of metacognition, in the evolution of human consciousness, has been emphasized by thinkers going back hundreds of years. While it is clear that people have metacognition, even when it is strictly defined as it is here, whether any other animals share this capability is the topic of this chapter. -

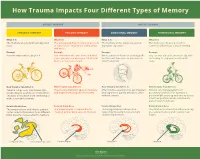

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Impacts of Training and Medication on Working Memory in Children with ADHD

APPLIED COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/acp.1589 Working Memory Deficits can be Overcome: Impacts of Training and Medication on Working Memory in Children with ADHD JONI HOLMES1*, SUSAN E. GATHERCOLE2, MAURICE PLACE3, DARREN L. DUNNING2, KERRY A. HILTON4 and JULIAN G. ELLIOTT4 1University of Northumbria, UK 2University of York, UK 3Hartlepool Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, UK 4Durham University, UK SUMMARY This study evaluated the impact of two interventions—a training program and stimulant medi- cation—on working memory (WM) function in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Twenty-five children aged between 8 and 11 years participated in training that taxed WM skills to the limit for a minimum of 20 days, and completed other assessments of WM and IQ before and after training, and with and without prescribed drug treatment. While medication significantly improved visuo-spatial memory performance, training led to substantial gains in all components of WM across untrained tasks. Training gains associated with the central executive persisted over a 6- month period. IQ scores were unaffected by either intervention. These findings indicate that the WM impairments in children with ADHD can be differentially ameliorated by training and by stimulant medication. Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. INTRODUCTION Working memory (WM), the cognitive system responsible for the temporary storage and manipulation of information, is crucial for maintaining focused behaviour in practical situations (Kane, Brown, McVay Silvia, Myin-Germeys, & Kwapil, 2007). Deficits in WM are typical among individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Barkley, 1997; Martinussen, Hayden, Hogg-Johnson, & Tannock, 2005). -

Hippocampal–Caudate Nucleus Interactions Support Exceptional Memory Performance

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-017-1556-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hippocampal–caudate nucleus interactions support exceptional memory performance Nils C. J. Müller1 · Boris N. Konrad1,2 · Nils Kohn1 · Monica Muñoz-López3 · Michael Czisch2 · Guillén Fernández1 · Martin Dresler1,2 Received: 1 December 2016 / Accepted: 24 October 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Participants of the annual World Memory competitive interaction between hippocampus and caudate Championships regularly demonstrate extraordinary mem- nucleus is often observed in normal memory function, our ory feats, such as memorising the order of 52 playing cards findings suggest that a hippocampal–caudate nucleus in 20 s or 1000 binary digits in 5 min. On a cognitive level, cooperation may enable exceptional memory performance. memory athletes use well-known mnemonic strategies, We speculate that this cooperation reflects an integration of such as the method of loci. However, whether these feats the two memory systems at issue-enabling optimal com- are enabled solely through the use of mnemonic strategies bination of stimulus-response learning and map-based or whether they benefit additionally from optimised neural learning when using mnemonic strategies as for example circuits is still not fully clarified. Investigating 23 leading the method of loci. memory athletes, we found volumes of their right hip- pocampus and caudate nucleus were stronger correlated Keywords Memory athletes · Method of loci · Stimulus with each other compared to matched controls; both these response learning · Cognitive map · Hippocampus · volumes positively correlated with their position in the Caudate nucleus memory sports world ranking. Furthermore, we observed larger volumes of the right anterior hippocampus in ath- letes. -

Cognitive Training with Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Cognitive Training With Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS Shaun Michael English Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation English, Shaun Michael, "Cognitive Training With Healthy Older Adults: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Brain Age Software for Nintendo DS" (2012). Dissertations (1934 -). 226. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/226 COGNITIVE TRAINING WITH HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS: INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE BRAIN AGETM SOFTWARE FOR NINTENDO By Shaun M. English, M.S. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin October 2012 ABSTRACT COGNITIVE TRAINING WITH HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS: INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE BRAIN AGETM SOFTWARE FOR NINTENDO Shaun M. English, M.S. Marquette University, 2012 An increasing number of empirical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive training (CT) with healthy, cognitively intact older adults. Less is known regarding the effectiveness of commercially available “brain training” programs. The current study investigated the impact of daily CT presented via the Brain Age® software for Nintendo DS on neurocognitive abilities in a sample of healthy, community-dwelling older adults. Over the six-week study, participants in the CT group completed training activities and were compared to an active control group who played card games on the Nintendo DS. At pre-test and post-test, a wide range of empirically validated neuropsychological outcome measures was administered to examine the proximal and distal transfer effects of training. -

Presentation on Working Memory

Executive Function: Working Memory Working Function: Executive Executive Function Skills: Working Memory Kris Baker [email protected] Imitation Game Working Memory: Explanations and Examples and Explanations Memory: Working Example: The ability to store and manage Recalling what you have just read and how it applies to what you are currently reading or being asked to do. information in one’s mind for a short period of time. Example: The manipulation of information Recalling the sequence in which a project, task or that short-term memory stores. activity needs to be completed. (Morin, 2016). Example: Remembering a phone The ability to keep one piece of number when trying to dial it. information in mind while working on or with something else (Smyth/Myles, 2016). In fact, most of the “work” in the memory system occurs in “working” memory where information is managed, manipulated and transformed (Can Learn, 2013). Struggles with Working Memory • Recalling sounds letters make when decoding a word (Smyth/Myles, 2016). • Recalling the meaning behind (the comprehension) of what you are reading when you are primarily focused on decoding or reading the words (learning to read vs reading to learn) • Slow retrieval of information (Can Learn, 2016). • Hold few pieces of information in their mind at a given moment in time: • “They hear what you said, or see what is presented, but as more information overwhelms their memory system they lose previous information needed to successfully complete the task. Once information is lost it is not likely to be retrieved. It is easy to see how the student can become frustrated and consequently stop paying attention.” (Can Learn, 2016). -

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize Anne Vetter, Daniel Gotz,¨ Sebastian von Mammen Games Engineering, University of Wurzburg,¨ Germany fanne.vetter,[email protected], [email protected] Abstract—There are uncountable things to be remembered, but assistance during comprehension (R6) of the information, e.g. most people were never shown how to memorize effectively. With by means of verbalization, should follow suit. Due to the this paper, the application The Art of Loci (TAoL) is presented, heterogeneity of learners, the applied process and methods to provide the means for efficient and fun learning. In a virtual reality (VR) environment users can express their study material should be individualized (R7) and strike a productive balance visually, either creating dimensional mind maps or experimenting between user’s choices and imposed learning activities (locus with mnemonic strategies, such as mind palaces. We also present of control) (R8). For example, users should be able to control common memorization techniques in light of their underlying the pace of learning. Learning environments should arouse the pedagogical foundations and discuss the respective features of intrinsic motivation of the user (R9). Fostering an awareness TAoL in comparison with similar software applications. of the learner’s cognition and thus reflection on their learning I. INTRODUCTION process and strategies is also beneficial (metacognition) (R10). Further, a constructivist learning approach can be realized by Before writing was common, information could only be the means to create artefacts such as representations, symbols preserved by memorization. Major ancient literature like The or cues (R11). Finally, cooperative and collaborative learning Iliad and The Odyssey were memorized, passed on through environments can benefit the learning process (R12).