Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

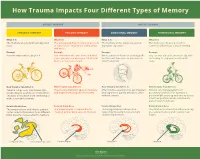

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement Or Self-Depletion?

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 05 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00469 Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement or Self-Depletion? Andrea Lavazza* Neuroethics, Centro Universitario Internazionale, Arezzo, Italy Autobiographical memory is fundamental to the process of self-construction. Therefore, the possibility of modifying autobiographical memories, in particular with memory-modulation and memory-erasing, is a very important topic both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the state of the art of some of the most promising areas of memory-modulation and memory-erasing, considering how they can affect the self and the overall balance of the “self and autobiographical memory” system. Indeed, different conceptualizations of the self and of personal identity in relation to autobiographical memory are what makes memory-modulation and memory-erasing more or less desirable. Because of the current limitations (both practical and ethical) to interventions on memory, I can Edited by: only sketch some hypotheses. However, it can be argued that the choice to mitigate Rossella Guerini, painful memories (or edit memories for other reasons) is somehow problematic, from an Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy ethical point of view, according to some of the theories of the self and personal identity Reviewed by: in relation to autobiographical memory, in particular for the so-called narrative theories Tillmann Vierkant, University of Edinburgh, of personal identity, chosen here as the main case of study. Other conceptualizations of United Kingdom the “self and autobiographical memory” system, namely the constructivist theories, do Antonella Marchetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, not have this sort of critical concerns. -

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES in Order to Remember Information, You First Have to Find It Somewhere in Your Memory

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES In order to remember information, you first have to find it somewhere in your memory. To be successful in college you need to use active learning strategies that help you store information and retrieve it. Mnemonic devices can help you do that. Mnemonics are techniques for remembering information that is otherwise difficult to recall. The idea behind using mnemonics is to encode complex information in a way that is much easier to remember. Two common types of mnemonic devices are acronyms and acrostics. Acronyms Acronyms are words made up of the first letters of other words. As a mnemonic device, acronyms help you remember the first letters of items in a list, which in turn helps you remember the list itself. Instructor OLC to accompany 100% Online Student Success 1 Examples The following are examples of popular mnemonic acronyms: HOMES Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior Names of the Great Lakes FACE The letters of the treble clef notes in the spaces from bottom to top spells “FACE”. ROY G. BIV Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Colors of the spectrum Violet MRS GREN Movement, Respiration, Sensitivity, Growth, Common attributes of living Reproduction, Excretion, Nutrition things Create Your Own Acronym Now think of a few words you need to remember. This could be related to your studies, your work, or just a subject of interest. Five steps to creating acronyms are*: 1. List the information you need to learn in meaningful phrases. 2. Circle or underline a keyword in each phrase. 3. Write down the first letter of each keyword. -

Learning Styles and Memory

Learning Styles and Memory Sandra E. Davis Auburn University Abstract The purpose of this article is to examine the relationship between learning styles and memory. Two learning styles were addressed in order to increase the understanding of learning styles and how they are applied to the individual. Specifically, memory phases and layers of memory will also be discussed. In conclusion, an increased understanding of the relationship between learning styles and memory seems to help the learner gain a better understanding of how to the maximize benefits for the preferred leaning style and how to retain the information in long-term memory. Introduction Learning styles, as identified in the Perpetual Learning Styles Theory and memory, as identified in the Memletics Accelerated Learning, will be overviewed. Factors involving information being retained into memory will then be discussed. This article will explain how the relationship between learning styles and memory can help the learner maximize his or her learning potential. Learning Styles The Perceptual Learning Styles Theory lists seven different styles. They are print, aural, interactive, visual, haptic, kinesthetic, and olfactory (Institute for Learning Styles Research, 2003). This theory says that most of what we learn comes from our five senses. The Perceptual Learning Style Theory defines the seven learning styles as follows: The print learning style individual prefers to see the written word (Institute for Learning Styles Research, 2003). They like taking notes, reading books, and seeing the written word, either on a chalk board or thru a media presentation such as Microsoft Powerpoint. The aural learner refers to listening (Institute for Learning Styles Research, 2003). -

ED 273 391 AUTHOR TITLE Metamemorial Knowledge, M-Space, and Working Memory PUB DATE Apr 86 NOTE 22P.; Paper Presented at the An

ED 273 391 PE 016 050 AUTHOR Ledger, George W.; Mca,ris, Kevin K. TITLE Metamemorial Knowledge, M-space, and Working Memory Performance in Fourth Graders. PUB DATE Apr 86 NOTE 22p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (67th, San Francisco, CA, April 16-20, 1986). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Elementary School Students; Grade 4; Intermediate Grades; *Memory; *Metacognition; *Predictor Variables IDENTIFIERS *Memory Span; *Metamemorial Knowledge ABSTRACT Three groups of fourth graders who differed on a metamemory pre-test were compared on five working memory tasks to explore the relationship between metamemorial knowledge, total processing space (M-space) and working memory span performance. Children in each group received three versions of each task on concurrent days. It was hypothesized that the group highest in metamemorial knowledge would score highest on the five working memory tasks. Results indicated that metamemory performance consistently predicted performance on the memory span measures. Three of the memory span measures showed a significant between-group effect on metamemory, while the remaining two evidenced strong trends in that direction. Analysis of repeated measures revealed no significant trials effects, indicating that no improvement in performance occurred across repeated presentations of the tasks. Implications for a metacognitive explanation of working memory processes and educational implications are discussed. (Author/RH) *******************************************i**************w*u********** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DRAFT COPY FOR CRITIQUE SESSION George W. Ledger American Educational Research Association and April, 1986 - San Francisco Kevin K. -

Disordered Memory Awareness: Recollective Confabulation in Two Cases of Persistent Déj`A Vecu

Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 1362–1378 Disordered memory awareness: recollective confabulation in two cases of persistent dej´ a` vecu Christopher J.A. Moulin a,b,∗, Martin A. Conway b, Rebecca G. Thompson a, Niamh James a, Roy W. Jones a a The Research Institute for the Care of the Elderly, St. Martin’s Hospital, UK b Institute of Psychological Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Received 7 April 2004; received in revised form 10 December 2004; accepted 16 December 2004 Available online 11 March 2005 Abstract We describe two cases of false recognition in patients with dementia and diffuse temporal lobe pathology who report their memory difficulty as being one of persistent dej´ a` vecu—the sensation that they have lived through the present moment before. On a number of recognition tasks, the patients were found to have high levels of false positives. They also made a large number of guess responses but otherwise appeared metacognitively intact. Informal reports suggested that the episodes of dej´ a` vecu were characterised by sensations similar to those present when the past is recollectively experienced in normal remembering. Two further experiments found that both patients had high levels of recollective experience for items they falsely recognized. Most strikingly, they were likely to recollectively experience incorrectly recognised low frequency words, suggesting that their false recognition was not driven by familiarity processes or vague sensations of having encountered events and stimuli before. Importantly, both patients made reasonable justifications for their false recognitions both in the experiments and in their everyday lives and these we term ‘recollective confabulation’. -

Memory Formation, Consolidation and Transformation

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 36 (2012) 1640–1645 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neubiorev Review Memory formation, consolidation and transformation a,∗ b a a L. Nadel , A. Hupbach , R. Gomez , K. Newman-Smith a Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, United States b Department of Psychology, Lehigh University, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Memory formation is a highly dynamic process. In this review we discuss traditional views of memory Received 29 August 2011 and offer some ideas about the nature of memory formation and transformation. We argue that memory Received in revised form 20 February 2012 traces are transformed over time in a number of ways, but that understanding these transformations Accepted 2 March 2012 requires careful analysis of the various representations and linkages that result from an experience. These transformations can involve: (1) the selective strengthening of only some, but not all, traces as a function Keywords: of synaptic rescaling, or some other process that can result in selective survival of some traces; (2) the Memory consolidation integration (or assimilation) of new information into existing knowledge stores; (3) the establishment Transformation Reconsolidation of new linkages within existing knowledge stores; and (4) the up-dating of an existing episodic memory. We relate these ideas to our own work on reconsolidation to provide some grounding to our speculations that we hope will spark some new thinking in an area that is in need of transformation. -

The Three Amnesias

The Three Amnesias Russell M. Bauer, Ph.D. Department of Clinical and Health Psychology College of Public Health and Health Professions Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute University of Florida PO Box 100165 HSC Gainesville, FL 32610-0165 USA Bauer, R.M. (in press). The Three Amnesias. In J. Morgan and J.E. Ricker (Eds.), Textbook of Clinical Neuropsychology. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis/Psychology Press. The Three Amnesias - 2 During the past five decades, our understanding of memory and its disorders has increased dramatically. In 1950, very little was known about the localization of brain lesions causing amnesia. Despite a few clues in earlier literature, it came as a complete surprise in the early 1950’s that bilateral medial temporal resection caused amnesia. The importance of the thalamus in memory was hardly suspected until the 1970’s and the basal forebrain was an area virtually unknown to clinicians before the 1980’s. An animal model of the amnesic syndrome was not developed until the 1970’s. The famous case of Henry M. (H.M.), published by Scoville and Milner (1957), marked the beginning of what has been called the “golden age of memory”. Since that time, experimental analyses of amnesic patients, coupled with meticulous clinical description, pathological analysis, and, more recently, structural and functional imaging, has led to a clearer understanding of the nature and characteristics of the human amnesic syndrome. The amnesic syndrome does not affect all kinds of memory, and, conversely, memory disordered patients without full-blown amnesia (e.g., patients with frontal lesions) may have impairment in those cognitive processes that normally support remembering. -

Eyewitness Metamemory Predicts Identification Performance in Biased and Unbiased Lineups

Eyewitness metamemory predicts identification performance in biased and unbiased lineups Renan Benigno Saraiva1,2*, Inger Mathilde van Boeijen3, Lorraine Hope1, Robert Horselenberg2, Melanie Sauerland3, Peter J. van Koppen2,4 1Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth 2Department of Criminal Law and Criminology, Maastricht University 3Department of Clinical Psychological Science, Maastricht University 4Department of Criminal Law and Criminology, VU University Amsterdam *Corresponding author: Renan Benigno Saraiva. Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science, University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom ([email protected]). Note: This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed. Please contact the authors before citing. Acknowledgements: This research was supported by a fellowship award from the Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate Program The House of Legal Psychology (EMJD-LP) with Framework Partnership Agreement (FPA) 2013-0036 and Specific Grant Agreement (SGA) 2013-0036. Metamemory and Eyewitness Identification 1 Abstract Distinguishing accurate from inaccurate identifications is a challenging issue in the criminal justice system, especially for biased police lineups. That is because biased lineups undermine the diagnostic value of accuracy postdictors such as confidence and decision time. Here, we aimed to test general and eyewitness-specific self-ratings of memory capacity as potential estimators of identification performance that are unaffected by lineup bias. Participants (N = 744) completed a metamemory assessment consisting of the Multifactorial Metamemory Questionnaire and the Eyewitness Metamemory Scale and took part in a standard eyewitness paradigm. Following the presentation of a mock-crime video, they viewed either biased or unbiased lineups. Self-ratings of discontentment with eyewitness memory ability were indicative of identification accuracy for both biased and unbiased lineups.