Explicit and Implicit Memory by Richard H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Episodic Memory in Transient Global Amnesia: Encoding, Storage, Or Retrieval Deficit?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.148 on 1 February 1999. Downloaded from 148 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:148–154 Episodic memory in transient global amnesia: encoding, storage, or retrieval deficit? Francis Eustache, Béatrice Desgranges, Peggy Laville, Bérengère Guillery, Catherine Lalevée, Stéphane SchaeVer, Vincent de la Sayette, Serge Iglesias, Jean-Claude Baron, Fausto Viader Abstract evertheless this division into processing stages Objectives—To assess episodic memory continues to be useful in helping understand (especially anterograde amnesia) during the working of memory systems”. These three the acute phase of transient global amne- stages may be defined in the following way: (1) sia to diVerentiate an encoding, a storage, encoding, during which perceptive information or a retrieval deficit. is transformed into more or less stable mental Methods—In three patients, whose am- representations; (2) storage (or consolidation), nestic episode fulfilled all current criteria during which mnemonic information is associ- for transient global amnesia, a neuro- ated with other representations and maintained psychological protocol was administered in long term memory; (3) retrieval, during which included a word learning task which the subject can momentarily reactivate derived from the Grober and Buschke’s mnemonic representations. These definitions procedure. will be used in the present study. Results—In one patient, the results sug- Regarding the retrograde amnesia of TGA, it gested an encoding deficit, -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Memory Reconsolidation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Current Biology Vol 23 No 17 R746 emerged from the pattern of amnesia consequence of this dynamic process Memory collectively caused by all these is that established memories, which reconsolidation different types of interventions. have reached a level of stability, can be Memory consolidation appeared to bidirectionally modulated and modified: be a complex and quite prolonged they can be weakened, disrupted Cristina M. Alberini1 process, during which different types or enhanced, and be associated and Joseph E. LeDoux1,2 of amnestic manipulation were shown to parallel memory traces. These to disrupt different mechanisms in the possibilities for trace strengthening The formation, storage and use of series of changes occurring throughout or weakening, and also for qualitative memories is critical for normal adaptive the consolidation process. The initial modifications via retrieval and functioning, including the execution phase of consolidation is known to reconsolidation, have important of goal-directed behavior, thinking, require a number of regulated steps behavioral and clinical implications. problem solving and decision-making, of post-translational, translational and They offer opportunities for finding and is at the center of a variety of gene expression mechanisms, and strategies that could change learning cognitive, addictive, mood, anxiety, blockade of any of these can impede and memory to make it more efficient and developmental disorders. Memory the entire consolidation process. and adaptive, to prevent or rescue also significantly contributes to the A century of studies on memory memory impairments, and to help shaping of human personality and consolidation proposed that, despite treat diseases linked to abnormally character, and to social interactions. -

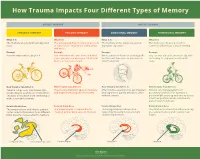

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W. D. Stevens, G. S. Wig, and D. L. Schacter, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ª 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 2.33.1 Introduction 623 2.33.2 Influences of Explicit Versus Implicit Memory 624 2.33.3 Top-Down Attentional Effects on Priming 626 2.33.3.1 Priming: Automatic/Independent of Attention? 626 2.33.3.2 Priming: Modulated by Attention 627 2.33.3.3 Neural Mechanisms of Top-Down Attentional Modulation 629 2.33.4 Specificity of Priming 630 2.33.4.1 Stimulus Specificity 630 2.33.4.2 Associative Specificity 632 2.33.4.3 Response Specificity 632 2.33.5 Priming-Related Increases in Neural Activation 634 2.33.5.1 Negative Priming 634 2.33.5.2 Familiar Versus Unfamiliar Stimuli 635 2.33.5.3 Sensitivity Versus Bias 636 2.33.6 Correlations between Behavioral and Neural Priming 637 2.33.7 Summary and Conclusions 640 References 641 2.33.1 Introduction stimulus that result from a previous encounter with the same or a related stimulus. Priming refers to an improvement or change in the When considering the link between behavioral identification, production, or classification of a stim- and neural priming, it is important to acknowledge ulus as a result of a prior encounter with the same or that functional neuroimaging relies on a number of a related stimulus (Tulving and Schacter, 1990). underlying assumptions. First, changes in informa- Cognitive and neuropsychological evidence indi- tion processing result in changes in neural activity cates that priming reflects the operation of implicit within brain regions subserving these processing or nonconscious processes that can be dissociated operations. -

Cognitive Functions of the Brain: Perception, Attention and Memory

IFM LAB TUTORIAL SERIES # 6, COPYRIGHT c IFM LAB Cognitive Functions of the Brain: Perception, Attention and Memory Jiawei Zhang [email protected] Founder and Director Information Fusion and Mining Laboratory (First Version: May 2019; Revision: May 2019.) Abstract This is a follow-up tutorial article of [17] and [16], in this paper, we will introduce several important cognitive functions of the brain. Brain cognitive functions are the mental processes that allow us to receive, select, store, transform, develop, and recover information that we've received from external stimuli. This process allows us to understand and to relate to the world more effectively. Cognitive functions are brain-based skills we need to carry out any task from the simplest to the most complex. They are related with the mechanisms of how we learn, remember, problem-solve, and pay attention, etc. To be more specific, in this paper, we will talk about the perception, attention and memory functions of the human brain. Several other brain cognitive functions, e.g., arousal, decision making, natural language, motor coordination, planning, problem solving and thinking, will be added to this paper in the later versions, respectively. Many of the materials used in this paper are from wikipedia and several other neuroscience introductory articles, which will be properly cited in this paper. This is the last of the three tutorial articles about the brain. The readers are suggested to read this paper after the previous two tutorial articles on brain structure and functions [17] as well as the brain basic neural units [16]. Keywords: The Brain; Cognitive Function; Consciousness; Attention; Learning; Memory Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Perception 3 2.1 Detailed Process of Perception . -

Introduction to "Implicit Memory: Multiple Perspectives"

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 1990. 28 (4). 338-340 Introduction to "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives" DANIEL L. SCHACTER University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona Psychological studies of memory have traditionally assessed retention of recently acquired in formation with recall and recognition tests that require intentional recollection or explicit memory for a study episode. During the past decade, there has been a growing interest in the experimen tal study of implicit memory: unintentional retrieval of information on tests that do not require any conscious recollection of a specific previous experience. Dissociations between explicit and implicit memory have been established, but theoretical interpretation ofthem remains controver sial. The present set of papers examines implicit memory from multiple perspectives-cognitive, developmental, psychophysiological, and neuropsychological-and addresses key methodological, empirical, and theoretical issues in this rapidly growing sector of memory research. The papers that follow were presented at a symposium Delaney, 1990; Tulving & Schacter, 1990), it is also pos entitled "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives," held sible to adopt a unitary or single-system view of memory at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society in At and still make use of the implicit/explicit distinction (e.g., lantaonNovember 17,1989. The symposium represents Roediger, Weldon, & Challis, 1989; Witherspoon & something of a milestone, in the sense that if someone Moscovitch, 1989). had suggested organizing an implicit memory symposium The distinction between implicit and explicit memory a decade ago, he or she probably would have been met is also closely related to the distinction between "direct" with a blank stare. That stare would have reflected two and "indirect" tests of memory (Johnson & Hasher, important facts: first, because the term "implicit 1987). -

Implicit Memory: How It Works and Why We Need It

Implicit Memory: How It Works and Why We Need It David W. L. Wu1 1University of British Columbia Correspondence to: [email protected] ABSTRACT Since the discovery that amnesiacs retained certain forms of unconscious learning and memory, implicit memory research has grown immensely over the past several decades. This review discusses two of the most intriguing questions in implicit memory research: how we think it works and why it is important to human behaviour. Using priming as an example, this paper surveys how historic behavioural studies have revealed how implicit memory differs from explicit memory. More recent neuroimaging studies are also discussed. These studies explore the neural correlate of priming and have led to the formation of the sharpening, fatigue, and facilitation neural models of priming. The latter part of this review discusses why humans have evolved with highly flexible explicit memory systems while still retaining inflexible implicit memory systems. Traditionally, researchers have regarded the competitive interaction between implicit and explicit memory systems to be fundamental for essential behaviours like habit learning. However, recently documented collaborative interactions suggest that both implicit and explicit processes are potentially necessary for optimal memory and learning performance. The literature reviewed in this paper reveals how implicit memory research has and continues to challenge our understanding of learning, memory, and the brain systems that underlie them. Keywords: implicit memory, priming, neural priming, habit learning INTRODUCTION several days despite having no recollection of the learning trials. For a time it was Not until Scoville and Milner believed that the acquisition of motor studied the amnesic patient H.M. -

Memory & Cognition

/ Memory & Cognition Volume 47 · Number 4 · May 2019 Special Issue: Recognizing Five Decades of Cumulative The role of control processes in temporal Progress in Understanding Human Memory and semantic contiguity and its Control Processes Inspired by Atkinson M.K. Healey · M.G. Uitvlugt 719 and Shiffrin (1968) Auditory distraction does more than disrupt rehearsal Guest Editors: Kenneth J. Malmberg· processes in children's serial recall Jeroen G. W. Raaijmakers ·Richard M. Shiffrin A.M. AuBuchon · C.l. McGill · E.M. Elliott 738 50 years of research sparked by Atkinson The effect of working memory maintenance and Shiffrin (1968) on long-term memory K.J. Malmberg · J.G.W. Raaijmakers · R.M. Shiffrin 561 J.K. Hartshorne· T. Makovski 749 · From ·short-term store to multicomponent working List-strength effects in older adults in recognition memory: The role of the modal model and free recall A.D. Baddeley · G.J. Hitch · R.J. Allen 575 L. Sahakyan 764 Central tendency representation and exemplar Verbal and spatial acquisition as a function of distributed matching in visual short-term memory practice and code-specific interference C. Dube 589 A.P. Young· A.F. Healy· M. Jones· L.E. Bourne Jr. 779 Item repetition and retrieval processes in cued recall: Dissociating visuo-spatial and verbal working memory: Analysis of recall-latency distributions It's all in the features Y. Jang · H. Lee 792 ~1 . Poirier· J.M. Yearsley · J. Saint-Aubin· C. Fortin· G. Gallant · D. Guitard 603 Testing the primary and convergent retrieval model of recall: Recall practice produces faster recall Interpolated retrieval effects on list isolation: success but also faster recall failure IndiYiduaLdifferences in working memory capacity W.J. -

Models of Memory

To be published in H. Pashler & D. Medin (Eds.), Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology, Third Edition, Volume 2: Memory and Cognitive Processes. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. MODELS OF MEMORY Jeroen G.W. Raaijmakers Richard M. Shiffrin University of Amsterdam Indiana University Introduction Sciences tend to evolve in a direction that introduces greater emphasis on formal theorizing. Psychology generally, and the study of memory in particular, have followed this prescription: The memory field has seen a continuing introduction of mathematical and formal computer simulation models, today reaching the point where modeling is an integral part of the field rather than an esoteric newcomer. Thus anything resembling a comprehensive treatment of memory models would in effect turn into a review of the field of memory research, and considerably exceed the scope of this chapter. We shall deal with this problem by covering selected approaches that introduce some of the main themes that have characterized model development. This selective coverage will emphasize our own work perhaps somewhat more than would have been the case for other authors, but we are far more familiar with our models than some of the alternatives, and we believe they provide good examples of the themes that we wish to highlight. The earliest attempts to apply mathematical modeling to memory probably date back to the late 19th century when pioneers such as Ebbinghaus and Thorndike started to collect empirical data on learning and memory. Given the obvious regularities of learning and forgetting curves, it is not surprising that the question was asked whether these regularities could be captured by mathematical functions.