Interactions Between Attention and Memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Dissociation Between Declarative and Procedural Mechanisms in Long-Term Memory

! DISSOCIATION BETWEEN DECLARATIVE AND PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN LONG-TERM MEMORY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Dale A. Hirsch August, 2017 ! A dissertation written by Dale A. Hirsch B.A., Cleveland State University, 2010 M.A., Cleveland State University, 2013 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Bradley Morris _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Christopher Was _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Karrie Godwin Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Lifespan Development and Mary Dellmann-Jenkins Educational Sciences _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human James C. Hannon Services ! ""! ! HIRSCH, DALE A., Ph.D., August 2017 Educational Psychology DISSOCIATION BETWEEN DECLARATIVE AND PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN LONG-TERM MEMORY (66 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Bradley Morris The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential dissociation between declarative and procedural elements in long-term memory for a facilitation of procedural memory (FPM) paradigm. FPM coupled with a directed forgetting (DF) manipulation was utilized to highlight the dissociation. Three experiments were conducted to that end. All three experiments resulted in facilitation for categorization operations. Experiments one and two additionally found relatively poor recognition for items that participants were told to forget despite the fact that relevant categorization operations were facilitated. Experiment three resulted in similarly poor recognition for category names that participants were told to forget. Taken together, the three experiments in this investigation demonstrate a clear dissociation between the procedural and declarative elements of the FPM task. -

Episodic Memory in Transient Global Amnesia: Encoding, Storage, Or Retrieval Deficit?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.148 on 1 February 1999. Downloaded from 148 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:148–154 Episodic memory in transient global amnesia: encoding, storage, or retrieval deficit? Francis Eustache, Béatrice Desgranges, Peggy Laville, Bérengère Guillery, Catherine Lalevée, Stéphane SchaeVer, Vincent de la Sayette, Serge Iglesias, Jean-Claude Baron, Fausto Viader Abstract evertheless this division into processing stages Objectives—To assess episodic memory continues to be useful in helping understand (especially anterograde amnesia) during the working of memory systems”. These three the acute phase of transient global amne- stages may be defined in the following way: (1) sia to diVerentiate an encoding, a storage, encoding, during which perceptive information or a retrieval deficit. is transformed into more or less stable mental Methods—In three patients, whose am- representations; (2) storage (or consolidation), nestic episode fulfilled all current criteria during which mnemonic information is associ- for transient global amnesia, a neuro- ated with other representations and maintained psychological protocol was administered in long term memory; (3) retrieval, during which included a word learning task which the subject can momentarily reactivate derived from the Grober and Buschke’s mnemonic representations. These definitions procedure. will be used in the present study. Results—In one patient, the results sug- Regarding the retrograde amnesia of TGA, it gested an encoding deficit, -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Working Memory and Cued Recall Max V

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Working memory and cued recall Max V. Fey 8602950 Karen Naufel Georgia Southern University Lawrence Locker Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Fey, Max V. 8602950; Naufel, Karen; and Locker, Lawrence, "Working memory and cued recall" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 220. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/220 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Working Memory and Cued Recall Working Memory and Cued Recall An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Psychology. By Maximilian Fey Under the mentorship of Dr. Karen Naufel ABSTRACT Previous research has found that individuals with high working memory have greater recall capabilities than those with low working memory (Unsworth, Spiller, & Brewers, 2012). Research did not test the extent to which cues affect one’s recall ability in relation to working memory. The present study will examine this issue. Participants completed a working memory measure. Then, they were provided with cued recall tasks whereby they recalled Facebook friends. The cues varied to be no cues, ambiguous cues high in imageability, and cues directly related to Facebook. The results showed that there was no difference between individual’s ability to recall their Facebook friends and their working memory scores. -

Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: the Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity

brain sciences Article Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: The Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity Vanesa Hidalgo 1,* , Carolina Villada 2 and Alicia Salvador 3 1 Department of Psychology and Sociology, Area of Psychobiology, University of Zaragoza, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Department of Psychology, Division of Health Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Leon 37670, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychobiology and IDOCAL, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-346 Received: 11 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: In contrast to the large body of research on the effects of stress-induced cortisol on memory consolidation in young people, far less attention has been devoted to understanding the effects of stress-induced testosterone on this memory phase. This study examined the psychobiological (i.e., anxiety, cortisol, and testosterone) response to the Maastricht Acute Stress Test and its impact on free recall and recognition for emotional and neutral material. Thirty-seven healthy young men and women were exposed to a stress (MAST) or control task post-encoding, and 24 h later, they had to recall the material previously learned. Results indicated that the MAST increased anxiety and cortisol levels, but it did not significantly change the testosterone levels. Post-encoding MAST did not affect memory consolidation for emotional and neutral pictures. Interestingly, however, cortisol reactivity was negatively related to free recall for negative low-arousal pictures, whereas testosterone reactivity was positively related to free recall for negative-high arousal and total pictures. -

The Effects of a Suggested Encoding Strategies on Achievement

The Effects of Metacognition 17 The Effects of Metacognition and Concrete Encoding Strategies on Depth of Understanding in Educational Psychology Suzanne Schellenberg, Meiko Negishi, & Paul Eggen, University of North Florida The study compared the academic achievement, as measured by final examination scores, of an experimental group of undergraduate educational psychology students who were provided with concrete mechanisms designed to promote metacognition and the use of specific encoding strategies to the achievement of a control group of similar students who were not provided with the same concrete mechanisms. The two groups were taught by the same instructor, who used the same teaching methods and identical class activities, homework, quizzes, and tests. The results indicated a statistically significant difference between the two groups, favoring the experimental group. Implications of the study for instruction and suggestions for further research are included. This study explored instructional capacity working memory that designs that encourage learners to consciously organizes information into become responsible for their own conceptual structures that make sense to learning. Responsible learners are the individual, a long-term memory that metacognitive, strategic, and high stores knowledge and skills in a achievers. Therefore, researchers have relatively permanent fashion, and become interested in investigating ways metacognitive monitoring that regulates to foster learners’ metacognition and this processing (Atkinson & Shiffrin, strategy use. 1968; Chandler & Sweller, 1990; Mayer The purpose of the study was to & Chandler, 2001; Paas, Renkl, & examine the impact of concrete Sweller, 2004; Sweller, 2003; Sweller, mechanisms for promoting van Merrienboer, & Paas, 1998). The metacognition and the conscious use of way knowledge is stored in long-term encoding strategies on the achievement memory has an important impact on of undergraduate educational learners’ ability to retrieve that psychology students. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

The Absent Minded Consumer

The Absentminded Consumer John Ameriks, Andrew Caplin and John Leahy∗ March 2003 (Preliminary) Abstract We present a model of an absentminded consumer who does not keep constant track of his spending. The model generates a form of precautionary consumption, in which absentminded agents tend to consume more than attentive agents. We show that wealthy agents are more likely to be absentminded, whereas young and retired agents are more likely to pay attenition. The model presents new explanations for a relationship between spending and credit card use and for the decline in consumption at retirement. Key Words: JEL Classification: 1 Introduction Doyouknowhowmuchyouspentlastmonth,andwhatyouspentiton?Itis only if you answer this question in the affirmative that the classical life-cycle model of consumption applies to you. Otherwise, you are to some extent an absent-minded consumer. In this paper we develop a theory that applies to thoseofuswhofallintothiscategory. The concept of absentmindedness that we employ in our analysis was introduced by Rubinstein and Piccione [1997]. They define absentmindedness as the inability to distinguish between decision nodes that lie along the same branch of a decision tree. By identifying these distinct nodes with different ∗We would like to thank Mark Gertler, Per Krusell, and Ricardo Lagos for helpful comments. 1 levels of spending, we are able to model consumers who are uncertain as to how much they spend in any given period. The effect of this change in model structure is to make it difficult for consumers to equate the marginal utility of consumption with the marginal utility of wealth. We show that this innocent twist in a standard consumption model may not only provide insight into some existing puzzles in the consumption literature, but also shed light on otherwise puzzling results concerning linkages between financial planning and wealth accumulation (Ameriks, Caplin, and Leahy [2003]). -

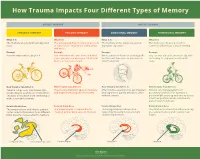

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Benefits of Stimulus-Driven Attention for Working Memory

Journal of Memory and Language 69 (2013) 384–396 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Memory and Language journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jml The benefits of stimulus-driven attention for working memory encoding ⇑ Susan M. Ravizza a, , Eliot Hazeltine b a Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, United States b Department of Psychology, University of Iowa, United States article info abstract Article history: The present study investigates how stimulus-driven attention to relevant information Received 18 July 2012 affects working memory performance. In three experiments, we examine whether stimu- revision received 30 May 2013 lus-driven attention to items can improve retention of these items in working memory. Available online 22 June 2013 Lists of phonologically-similar and dissimilar items were presented at expected or unex- pected locations in Experiment 1. When stimulus-driven attention was captured by items Keywords: presented at unexpected locations, similar items were better remembered than similar Verbal working memory items that appeared at expected locations. These results were replicated in Experiment 2 Attentional capture using contingent capture to boost stimulus-driven attention to similar items. Experiment Short term memory 3 demonstrated that stimulus-driven attention was beneficial for both similar and dissim- ilar items when the latter condition was made more difficult. Together, these experiments demonstrate that stimulus-driven attention to relevant information is one mechanism by which encoding can be facilitated. Ó 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction strated in research examining the detrimental effects on WM performance when stimulus-driven attention is cap- Working memory (WM) keeps information in an active tured by irrelevant distractors (Anticevic, Repovs, Shul- state for a short period of time so that it can be readily ac- man, & Barch, 2009; Majerus et al., 2012; Olesen, cessed and manipulated in the service of immediate task Macoveanu, Tegner, & Klingberg, 2007; West, 1999).