About Sleep's Role in Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Müller and Pilzecker

PERSPECTIVE Hilde A. Lechner,1 100 Years of Consolidation— Larry R. Squire,2 and John H. Byrne Remembering Mu¨ller and Pilzecker 1W.M. Keck Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy University of Texas–Houston Medical School Houston, Texas 77030 USA 2Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Diego and Departments of Psychiatry, Neurosciences, and Psychology University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92093 USA Introduction The origin of the concept of memory consolidation and the introduction of the term “consolidirung” (consolidation) to the modern science of memory are generally credited to Georg Elias Mu¨ller (1850–1934), professor at the University of Göttingen, Germany, and his student Alfons Pilzecker. Their seminal monograph “Experimentelle Beitra¨ge zur Lehre vom Geda¨chtnis” (Experimental Contributions to the Science of Memory), published in 1900, proposed that learning does not induce instantaneous, permanent memories but that memory takes time to be fixed (or consolidated). Consequently, memory remains vulnerable to disruption for a period of time after learning. Georg Mu¨ller was among the founders of experimental psychology. Inspired by the work of Gustav Fechner (1801–1887), Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920), and Herman Ebbinghaus (1859–1909),1 he was an early advocate of the view that mental function results from the action of matter, and that learning and memory should thus exhibit lawful properties. In their 300-page monograph, Mu¨ller and Pilzecker reported 40 experiments, carried out between 1892 and 1900, which were designed to identify the laws that govern memory formation and retrieval. Although Mu¨ller and Pilzecker have been frequently acknowledged for introducing the concept of memory consolidation,2 their monograph has not been translated and knowledge of their methods and experimental findings has faded with the passing of almost a century. -

Implicit Memory in Amnesic Patients: When Is Auditory Priming Spared?

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (1995), 1, 434-442. Copyright © 1995 INS. Published by Cambridge University Press. Printed in the USA. Implicit memory in amnesic patients: When is auditory priming spared? DANIEL L. SCHACTER1 AND BARBARA CHURCH2 1 Harvard University and Memory Disorders Research Center, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Cambridge, MA 02138 2 University of Illinois, Champaign, IL 61820 (RECEIVED February 16, 1995; ACCEPTED March 2, 1995) Abstract Amnesic patients often exhibit spared priming effects on implicit memory tests despite poor explicit memory. In previous research, we found normal auditory priming in amnesic patients on a task in which the magnitude of priming in control subjects was independent of whether speaker's voice was same or different at study and test, and found impaired voice-specific priming on a task in which priming in control subjects is higher when speaker's voice is the same at study and test than when it is different. The present experiments provide further evidence of spared auditory priming in amnesia, demonstrate that normal priming effects are not an artifact of low levels of baseline performance, and provide suggestive evidence that amnesic patients can exhibit voice-specific priming when experimental conditions do not require them to interactively bind together word and voice information. (JINS, 1995, 7, 434-442.) Keywords: Amnesia, Priming, Implicit memory Introduction jects heard a list of spoken words and judged either the category to which each word belongs (semantic encoding It is well known that amnesic patients can exhibit robust task) or the pitch of the speaker's voice (nonsemantic en- implicit memory despite impaired explicit memory. -

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Episodic Memory in Transient Global Amnesia: Encoding, Storage, Or Retrieval Deficit?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.148 on 1 February 1999. Downloaded from 148 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:148–154 Episodic memory in transient global amnesia: encoding, storage, or retrieval deficit? Francis Eustache, Béatrice Desgranges, Peggy Laville, Bérengère Guillery, Catherine Lalevée, Stéphane SchaeVer, Vincent de la Sayette, Serge Iglesias, Jean-Claude Baron, Fausto Viader Abstract evertheless this division into processing stages Objectives—To assess episodic memory continues to be useful in helping understand (especially anterograde amnesia) during the working of memory systems”. These three the acute phase of transient global amne- stages may be defined in the following way: (1) sia to diVerentiate an encoding, a storage, encoding, during which perceptive information or a retrieval deficit. is transformed into more or less stable mental Methods—In three patients, whose am- representations; (2) storage (or consolidation), nestic episode fulfilled all current criteria during which mnemonic information is associ- for transient global amnesia, a neuro- ated with other representations and maintained psychological protocol was administered in long term memory; (3) retrieval, during which included a word learning task which the subject can momentarily reactivate derived from the Grober and Buschke’s mnemonic representations. These definitions procedure. will be used in the present study. Results—In one patient, the results sug- Regarding the retrograde amnesia of TGA, it gested an encoding deficit, -

Auditory Feedback Blocks Memory Benefits of Cueing During Sleep

ARTICLE Received 26 Feb 2015 | Accepted 25 Sep 2015 | Published 28 Oct 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9729 OPEN Auditory feedback blocks memory benefits of cueing during sleep Thomas Schreiner1,2, Mick Lehmann1,3 & Bjo¨rn Rasch1,2,4 It is now widely accepted that re-exposure to memory cues during sleep reactivates memories and can improve later recall. However, the underlying mechanisms are still unknown. As reactivation during wakefulness renders memories sensitive to updating, it remains an intriguing question whether reactivated memories during sleep also become susceptible to incorporating further information after the cue. Here we show that the memory benefits of cueing Dutch vocabulary during sleep are in fact completely blocked when memory cues are directly followed by either correct or conflicting auditory feedback, or a pure tone. In addition, immediate (but not delayed) auditory stimulation abolishes the characteristic increases in oscillatory theta and spindle activity typically associated with successful reactivation during sleep as revealed by high-density electroencephalography. We conclude that plastic processes associated with theta and spindle oscillations occurring during a sensitive period immediately after the cue are necessary for stabilizing reactivated memory traces during sleep. 1 Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, 8050 Zurich, Switzerland. 2 Department of Psychology, University of Fribourg, 1701 Fribourg, Switzerland. 3 Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, Clinic of Affective Disorders and General Psychiatry, 8032 Zurich, Switzerland. 4 Zurich Center for Interdisciplinary Sleep Research (ZiS), 8091 Zurich, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to B.R. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:8729 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9729 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: the Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity

brain sciences Article Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: The Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity Vanesa Hidalgo 1,* , Carolina Villada 2 and Alicia Salvador 3 1 Department of Psychology and Sociology, Area of Psychobiology, University of Zaragoza, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Department of Psychology, Division of Health Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Leon 37670, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychobiology and IDOCAL, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-346 Received: 11 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: In contrast to the large body of research on the effects of stress-induced cortisol on memory consolidation in young people, far less attention has been devoted to understanding the effects of stress-induced testosterone on this memory phase. This study examined the psychobiological (i.e., anxiety, cortisol, and testosterone) response to the Maastricht Acute Stress Test and its impact on free recall and recognition for emotional and neutral material. Thirty-seven healthy young men and women were exposed to a stress (MAST) or control task post-encoding, and 24 h later, they had to recall the material previously learned. Results indicated that the MAST increased anxiety and cortisol levels, but it did not significantly change the testosterone levels. Post-encoding MAST did not affect memory consolidation for emotional and neutral pictures. Interestingly, however, cortisol reactivity was negatively related to free recall for negative low-arousal pictures, whereas testosterone reactivity was positively related to free recall for negative-high arousal and total pictures. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

Science Current Directions in Psychological

Current Directions in Psychological Science http://cdp.sagepub.com/ A Theory About Why We Forget What We Once Knew John T. Wixted Current Directions in Psychological Science 2005 14: 6 DOI: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00324.x The online version of this article can be found at: http://cdp.sagepub.com/content/14/1/6 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Association for Psychological Science Additional services and information for Current Directions in Psychological Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cdp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cdp.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Feb 1, 2005 What is This? Downloaded from cdp.sagepub.com at The University of Iowa Libraries on October 8, 2011 CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE A Theory About Why We Forget What We Once Knew John T. Wixted University of California, San Diego ABSTRACT—Traditional theories of forgetting assume that of your first-grade teacher, thereby proving that the information everyday forgetting is a cue-overload phenomenon, and was encoded, you may now discover that the name has slipped the primary laboratory method used for investigating that away (forever, perhaps). Why does that happen? Traditionally, phenomenon has long been the A-B, A-C paired-associates the answer has been that forgetting occurs either because procedure. A great deal of research in psychology, psy- memories naturally decay or because they succumb to the forces chopharmacology, and neuroscience suggests that this of interference. The story that most students of psychology learn approach to the study of forgetting may not be very rele- is that a classic sleep study conducted by Jenkins and Dal- vant to the kind of interference that induces most forget- lenbach (1924) tilted the balance in favor of interference theory. -

Discovery Misattribution: When Solving Is Confused with Remembering

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association 2007, Vol. 136, No. 4, 577–592 0096-3445/07/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.577 Discovery Misattribution: When Solving Is Confused With Remembering Sonya Dougal Jonathan W. Schooler New York University University of British Columbia This study explored the discovery misattribution hypothesis, which posits that the experience of solving an insight problem can be confused with recognition. In Experiment 1, solutions to successfully solved anagrams were more likely to be judged as old on a recognition test than were solutions to unsolved anagrams regardless of whether they had been studied. Experiment 2 demonstrated that anagram solving can increase the proportion of “old” judgments relative to words presented outright. Experiment 3 revealed that under certain conditions, solving anagrams influences the proportion of “old” judgments to unrelated items immediately following the solved item. In Experiment 4, the effect of solving was reduced by the introduction of a delay between solving the anagrams and the recognition judgments. Finally, Experiments 5 and 6 demonstrated that anagram solving leads to an illusion of recollection. Keywords: recognition, memory misattribution, recollection, insight problem There is something very similar about the experience of recol- found that increasing the perceptual fluency of items on a recog- lection and that of discovery. In both cases, a thought comes to nition test by preceding them with subliminally -

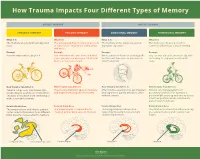

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Sleep's Role on Episodic Memory Consolidation

SLEEP ’S ROLE ON EPISODIC MEMORY CONSOLIDATION IN ADULTS AND CHILDREN Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät und der Medizinischen Fakultät der Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen vorgelegt von Jing-Yi Wang aus Shijiazhuang, Hebei, Volksrepublik China Dezember, 2016 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: February 22 , 2017 Dekan der Math.-Nat. Fakultät: Prof. Dr. W. Rosenstiel Dekan der Medizinischen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. I. B. Autenrieth 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Jan Born 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Steffen Gais Prüfungskommission: Prof. Manfred Hallschmid Prof. Dr. Steffen Gais Prof. Christoph Braun Prof. Caterina Gawrilow I Declaration: I hereby declare that I have produced the work entitled “Sleep’s Role on Episodic Memory Consolidation in Adults and Children”, submitted for the award of a doctorate, on my own (without external help), have used only the sources and aids indicated and have marked passages included from other works, whether verbatim or in content, as such. I swear upon oath that these statements are true and that I have not concealed anything. I am aware that making a false declaration under oath is punishable by a term of imprisonment of up to three years or by a fine. Tübingen, the December 5, 2016 ........................................................ Date Signature III To my beloved parents – Hui Jiao and Xuewei Wang, Grandfather – Jin Wang, and Frederik D. Weber 致我的父母:焦惠和王学伟 爷爷王金,以及 爱人王敬德 V Content Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................................