The Memory of What We Do Not Recall: Dissociations and Theoretical Debates in the Study of Implicit Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissociation Between Declarative and Procedural Mechanisms in Long-Term Memory

! DISSOCIATION BETWEEN DECLARATIVE AND PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN LONG-TERM MEMORY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Dale A. Hirsch August, 2017 ! A dissertation written by Dale A. Hirsch B.A., Cleveland State University, 2010 M.A., Cleveland State University, 2013 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Bradley Morris _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Christopher Was _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Karrie Godwin Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Lifespan Development and Mary Dellmann-Jenkins Educational Sciences _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human James C. Hannon Services ! ""! ! HIRSCH, DALE A., Ph.D., August 2017 Educational Psychology DISSOCIATION BETWEEN DECLARATIVE AND PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN LONG-TERM MEMORY (66 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Bradley Morris The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential dissociation between declarative and procedural elements in long-term memory for a facilitation of procedural memory (FPM) paradigm. FPM coupled with a directed forgetting (DF) manipulation was utilized to highlight the dissociation. Three experiments were conducted to that end. All three experiments resulted in facilitation for categorization operations. Experiments one and two additionally found relatively poor recognition for items that participants were told to forget despite the fact that relevant categorization operations were facilitated. Experiment three resulted in similarly poor recognition for category names that participants were told to forget. Taken together, the three experiments in this investigation demonstrate a clear dissociation between the procedural and declarative elements of the FPM task. -

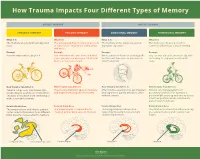

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Implicit Stereotypes and the Predictive Brain: Cognition and Culture in “Biased” Person Perception

ARTICLE Received 28 Jan 2017 | Accepted 17 Jul 2017 | Published 1 Sep 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.86 OPEN Implicit stereotypes and the predictive brain: cognition and culture in “biased” person perception Perry Hinton1 ABSTRACT Over the last 30 years there has been growing research into the concept of implicit stereotypes. Particularly using the Implicit Associations Test, it has been demon- strated that experimental participants show a response bias in support of a stereotypical association, such as “young” and “good” (and “old” and “bad”) indicating evidence of an implicit age stereotype. This has been found even for people who consciously reject the use of such stereotypes, and seek to be fair in their judgement of other people. This finding has been interpreted as a “cognitive bias”, implying an implicit prejudice within the individual. This article challenges that view: it is argued that implicit stereotypical associations (like any other implicit associations) have developed through the ordinary working of “the predictive brain”. The predictive brain is assumed to operate through Bayesian principles, developing associations through experience of their prevalence in the social world of the perceiver. If the predictive brain were to sample randomly or comprehensively then stereotypical associations would not be picked up if they did not represent the state of the world. However, people are born into culture, and communicate within social networks. Thus, the implicit stereotypical associations picked up by an individual do not reflect a cognitive bias but the associations prevalent within their culture—evidence of “culture in mind”. Therefore to understand implicit stereotypes, research should examine more closely the way associations are communicated within social networks rather than focusing exclusively on an implied cognitive bias of the individual. -

Memory in Mind and Culture

This page intentionally left blank Memory in Mind and Culture This text introduces students, scholars, and interested educated readers to the issues of human memory broadly considered, encompassing individual mem- ory, collective remembering by societies, and the construction of history. The book is organized around several major questions: How do memories construct our past? How do we build shared collective memories? How does memory shape history? This volume presents a special perspective, emphasizing the role of memory processes in the construction of self-identity, of shared cultural norms and concepts, and of historical awareness. Although the results are fairly new and the techniques suitably modern, the vision itself is of course related to the work of such precursors as Frederic Bartlett and Aleksandr Luria, who in very different ways represent the starting point of a serious psychology of human culture. Pascal Boyer is Henry Luce Professor of Individual and Collective Memory, departments of psychology and anthropology, at Washington University in St. Louis. He studied philosophy and anthropology at the universities of Paris and Cambridge, where he did his graduate work with Professor Jack Goody, on memory constraints on the transmission of oral literature. He has done anthro- pological fieldwork in Cameroon on the transmission of the Fang oral epics and on Fang traditional religion. Since then, he has worked mostly on the experi- mental study of cognitive capacities underlying cultural transmission. After teaching in Cambridge, San Diego, Lyon, and Santa Barbara, Boyer moved to his present position at the departments of anthropology and psychology at Washington University, St. Louis. James V. -

Sources of Confidence Judgments in Implicit Cognition

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2005, 12 (2), 367-373 Sources of confidence judgments in implicit cognition RICHARD J. TUNNEY University of Nottingham, Nottingham, England Subjective reports of confidence are frequently used as a measure of awareness in a variety of fields, including artificial grammar learning. However, little is known about what information is used to make confidence judgments and whether there are any possible sources of information used to discriminate between items that are unrelated to confidence. The data reported here replicate an earlier experiment by Vokey and Brooks (1992) and show that grammaticality decisions are based on both the grammati- cal status of items and their similarity to study exemplars. The key finding is that confidence ratings made on a continuous scale (50%–100%) are closely related to grammaticality but are unrelated to all of the measures of similarity that were tested. By contrast, confidence ratings made on a binary scale (high vs. low) are related to both grammaticality and similarity. The data confirm an earlier finding (Tunney & Shanks, 2003) that binary confidence ratings are more sensitive to low levels of awareness than continuous ratings are and suggest that participants are conscious of all the information acquired in artificial grammar learning. For many years, subjective reports of confidence have edge with low confidence may, therefore, not be reported been used to distinguish between conscious and uncon- even if, in fact, conscious. An alternative to verbal report scious cognitive processes in areas as diverse as discrim- is to ask participants to rate how confident they are that ination (Peirce & Jastrow, 1884), perception (Cheesman their judgments are correct or, alternately, to estimate & Merikle, 1984; Kunimoto, Miller, & Pashler, 2001), their overall level of accuracy. -

PSYC20006 Notes

PSYC20006 BIOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY PSYC20006 1 COGNITIVE THEORIES OF MEMORY Procedural Memory: The storage of skills & procedures, key in motor performance. It involves memory systems that are independent of the hippocampal formation, in particular, the cerebellum, basal ganglia, cortical motor sites. Doesn't involve mesial-temporal function, basal forebrain or diencephalon. Declarative memory: Accumulation of facts/data from learning experiences. • Associated with encoding & maintaining information, which comes from higher systems in the brain that have processed the information • Information is then passed to hippocampal formation, which does the encoding for elaboration & retention. Hippocampus is in charge of structuring our memories in a relational way so everything relating to the same topic is organized within the same network. This is also how memories are retrieved. Activation of 1 piece of information will link up the whole network of related pieces of information. Memories are placed into an already exiting framework, and so memory activation can be independent of the environment. MODELS OF MEMORY Serial models of Memory include the Atkinson-Shiffrin Model, Levels of Processing Model & Tulving’s Model — all suggest that memory is processed in a sequential way. A parallel model of memory, the Parallel Distributed Processing Model, is one which suggests types of memories are processed independently. Atkinson-Shiffrin Model First starts as Sensory Memory (visual / auditory). If nothing is done with it, fades very quickly but if you pay attention to it, it will move into working memory. Working Memory contains both new information & from long-term memory. If it goes through an encoding process, it will be in long-term memory. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

1 the Psychology of Implicit Intergroup Bias and the Prospect Of

1 The Psychology of Implicit Intergroup Bias and the Prospect of Change Calvin K. Lai1 & Mahzarin R. Banaji2 1 Washington University in St. Louis 2 Harvard University Last updated: June 24, 2020 Correspondence should be addressed to: Calvin Lai at [email protected]. Paper should be cited as: Lai, C. K., & Banaji, M. R. (2020). The psychology of implicit intergroup bias and the prospect of change. In D. Allen & R. Somanathan (Eds.), Difference without Domination: Pursuing Justice in Diverse Democracies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 2 1. Introduction Over the course of evolution, human minds acquired the breathtaking quality of consciousness which gave our species the capacity to regulate behavior. Among the consequences of this capacity was the possibility of internal dialogue with oneself about the consistency between one’s intentions and actions. This facility to engage in the daily rituals of deliberative thought and action is so natural to our species that we hardly reflect on it or take stock of how effectively we are achieving the goal of intention-action consistency. We do not routinely ask at the end of each day how many of our actions were consistent with the values so many individuals hold: a belief in freedom and equality for all, in opportunity and access for all, in fairness in treatment and justice for all. Even if we wished to compute the extent to which we succeed at this task, how would we go about doing it? As William James (1904) pointed over a century ago, the difficulty of studying the human mind is that the knower is also the known, and this poses difficulties in accessing, in modestly objective fashion, the data from our own moral ledger. -

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W. D. Stevens, G. S. Wig, and D. L. Schacter, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ª 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 2.33.1 Introduction 623 2.33.2 Influences of Explicit Versus Implicit Memory 624 2.33.3 Top-Down Attentional Effects on Priming 626 2.33.3.1 Priming: Automatic/Independent of Attention? 626 2.33.3.2 Priming: Modulated by Attention 627 2.33.3.3 Neural Mechanisms of Top-Down Attentional Modulation 629 2.33.4 Specificity of Priming 630 2.33.4.1 Stimulus Specificity 630 2.33.4.2 Associative Specificity 632 2.33.4.3 Response Specificity 632 2.33.5 Priming-Related Increases in Neural Activation 634 2.33.5.1 Negative Priming 634 2.33.5.2 Familiar Versus Unfamiliar Stimuli 635 2.33.5.3 Sensitivity Versus Bias 636 2.33.6 Correlations between Behavioral and Neural Priming 637 2.33.7 Summary and Conclusions 640 References 641 2.33.1 Introduction stimulus that result from a previous encounter with the same or a related stimulus. Priming refers to an improvement or change in the When considering the link between behavioral identification, production, or classification of a stim- and neural priming, it is important to acknowledge ulus as a result of a prior encounter with the same or that functional neuroimaging relies on a number of a related stimulus (Tulving and Schacter, 1990). underlying assumptions. First, changes in informa- Cognitive and neuropsychological evidence indi- tion processing result in changes in neural activity cates that priming reflects the operation of implicit within brain regions subserving these processing or nonconscious processes that can be dissociated operations. -

Associative Repetition Priming: a Selective Review and Theoretical Implications

Associative repetition priming 1 Running head: Associative Repetition Priming Associative repetition priming: A selective review and theoretical implications René Zeelenberg University of Amsterdam Diane Pecher Utrecht University and Jeroen G.W. Raaijmakers University of Amsterdam Send correspondence to: René Zeelenberg Psychology Department Associative repetition priming 2 Indiana University Bloomington, IN 47405 USA phone: 001-812-856-5217 fax: 001-812-855-1086 email: [email protected] Associative repetition priming 3 A. Introduction An extensive body of research in the last two decades has shown that recent experiences can affect performance even when subjects are not instructed to remember these earlier experiences and even when subjects are not aware of these experiences. These so-called implicit memory phenomena are usually demonstrated by the repetition priming effect. Repetition priming refers to the finding that responses are faster and more accurate to stimuli that have been encountered recently than to stimuli that have not been encountered recently. For example, in a perceptual word identification task (Jacoby & Dallas, 1981; Salasoo, Shiffrin & Feustel, 1985) subjects can more often correctly identify the briefly flashed target word if they have recently studied the target than if they have not studied the target. Comparable effects have been obtained in tasks such as picture identification (e.g., Rouder, Ratcliff & McKoon, 2000), word stem completion (e.g., Graf, Squire, & Mandler, 1984) and lexical decision (e.g., Bowers & Michita, 1998; Scarborough, Cortese, & Scarborough, 1977), to name but a few. The large majority of studies in the domain of implicit memory have concentrated on the effect of repeating stimuli in isolation. In the common repetition priming paradigm stimuli are presented one-by-one both during the study phase and the test phase. -

The Declarative/Procedural Model Michael T

Cognition 92 (2004) 231–270 www.elsevier.com/locate/COGNIT Contributions of memory circuits to language: the declarative/procedural model Michael T. Ullman* Brain and Language Laboratory, Departments of Neuroscience, Linguistics, Psychology and Neurology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA Received 12 December 2001; revised 13 December 2002; accepted 29 October 2003 Abstract The structure of the brain and the nature of evolution suggest that, despite its uniqueness, language likely depends on brain systems that also subserve other functions. The declarative/procedural (DP) model claims that the mental lexicon of memorized word-specific knowledge depends on the largely temporal-lobe substrates of declarative memory, which underlies the storage and use of knowledge of facts and events. The mental grammar, which subserves the rule-governed combination of lexical items into complex representations, depends on a distinct neural system. This system, which is composed of a network of specific frontal, basal-ganglia, parietal and cerebellar structures, underlies procedural memory, which supports the learning and execution of motor and cognitive skills, especially those involving sequences. The functions of the two brain systems, together with their anatomical, physiological and biochemical substrates, lead to specific claims and predictions regarding their roles in language. These predictions are compared with those of other neurocognitive models of language. Empirical evidence is presented from neuroimaging studies of normal language processing, and from developmental and adult-onset disorders. It is argued that this evidence supports the DP model. It is additionally proposed that “language” disorders, such as specific language impairment and non-fluent and fluent aphasia, may be profitably viewed as impairments primarily affecting one or the other brain system.