Implicit and Explicit Memory for Novel Visual Objects in Older and \Bunger Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory Control: Investigating the Consequences and Mechanisms of Directed Forgetting in Working Memory

Memory Control: Investigating the Consequences and Mechanisms of Directed Forgetting in Working Memory by Sara B. Festini A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Patricia A. Reuter-Lorenz, Chair Professor John Jonides Associate Professor Cindy A. Lustig Associate Professor Rachael D. Seidler © Sara B. Festini 2014 Dedication To my family. Thank you for all of your love, support, and encouragement! ii Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my primary advisor, Patti Reuter-Lorenz, for her continued guidance, support, and mentorship throughout my time at the University of Michigan. I am extremely grateful for all of the knowledge and advice she provided, which has made me a better scientist, writer, and thinker. Every experiment in my dissertation benefited from Patti’s wisdom, and I look forward to our continued academic collaboration in years to come. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, John Jonides, Cindy Lustig, and Rachael Seidler, for their valuable feedback on my dissertation. Each committee meeting strengthened my dissertation and opened my eyes to new and important viewpoints. I would like to especially thank John for taking the time to read and provide comments on all of the manuscripts comprising this dissertation. His expertise in cognitive control considerably strengthened the arguments and interpretation of my research, for which I am extremely appreciative. Moreover, I want to thank Rachael Seidler for welcoming me into her lab to conduct additional independent research projects. I greatly valued being exposed to different types of research paradigms and analyses, including the wonderful opportunity to analyze resting state functional connectivity data and to pursue my interest in motor learning. -

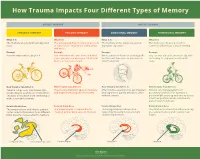

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Wolk DA, Schacter DL, Berman AR, Holcomb PJ, Daffner KR, Budson

Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 1662–1672 Patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease attribute conceptual fluency to prior experience David A. Wolk a, b, ∗, Daniel L. Schacter c, Alyssa R. Berman b, Phillip J. Holcomb d, Kirk R. Daffner a, b, Andrew E. Budson b, e a Harvard Medical School, 25 Shattuck Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA b Division of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1620 Tremont Street, 221 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115, USA c Department of Psychology, Harvard University, 33 Kirkland Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA d Department of Psychology, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155, USA e Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center, Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital, 200 Springs Road, Bedford MA 01730, USA Received 26 October 2004; received in revised form 12 January 2005; accepted 13 January 2005 Available online 23 February 2005 Abstract Patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been found to be relatively dependent on familiarity in their recognition memory judgments. Conceptual fluency has been argued to be an important basis of familiarity. This study investigated the extent to which patients with mild AD use conceptual fluency cues in their recognition decisions. While no evidence of recognition memory was found in the patients with AD, enhanced conceptual fluency was associated with a higher rate of “Old” responses (items endorsed as having been studied) compared to when fluency was not enhanced. The magnitude of this effect was similar for patients with AD and healthy control participants. Additionally, ERP recordings time-locked to test item presentation revealed preserved modulations thought critical to the effect of conceptual fluency on test performance (N400 and late frontal components) in the patients with AD, consistent with the behavioral results. -

Cognitive and Neuropsychological Aspects of Age-Associated Memory Dysfunction

COGNITIVE AND NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF AGE-ASSOCIATED MEMORY DYSFUNCTION A k a d e m is k a v h a n d l in g som för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen med vederbörligt tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet framlägges för offentlig granskning vid Psykologiska institutionen, Umeå Universitet, Seminarierum 2, fredagen den 24 januari 1992, klockan 10.15 AV Th o m a s K a r l s s o n Psykologiska institutionen, Umeå Universitet, Umeå COGNITIVE AND NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF AGE- ASSOCIATED MEMORY DYSFUNCTION BY Thom as K arlsson Doctoral Dissertation Department of Psychology, University of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden ABSTRACT Memory dysfunction is common in association with the course of normal aging. Memory dysfunction is also obligatory in age-associated neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. However, despite the ubiquitousness of age-related memory decline, several basic questions regarding this entity remain unanswered. The present investigation addressed two such questions: (1) Can individuals suffering from memory dysfunction due to aging and amnesia due to Alzheimer’s disease improve memory performance if contextual support is provided at the time of acquisition of to-be- remembered material or reproduction of to-be-remembered material? (2) Are memory deficits observed in ‘younger’ older adults similar to the deficits observed in ‘older’ elderly subjects, Alzheimer’s disease, and memory dysfunction in younger subjects? The outcome of this investigation suggests an affirmative answer to the first question. Given appropriate support at encoding and retrieval, even densely amnesic patients can improve their memory performance. As to the second question, a more complex pattern emerges. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

Introduction to "Implicit Memory: Multiple Perspectives"

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 1990. 28 (4). 338-340 Introduction to "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives" DANIEL L. SCHACTER University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona Psychological studies of memory have traditionally assessed retention of recently acquired in formation with recall and recognition tests that require intentional recollection or explicit memory for a study episode. During the past decade, there has been a growing interest in the experimen tal study of implicit memory: unintentional retrieval of information on tests that do not require any conscious recollection of a specific previous experience. Dissociations between explicit and implicit memory have been established, but theoretical interpretation ofthem remains controver sial. The present set of papers examines implicit memory from multiple perspectives-cognitive, developmental, psychophysiological, and neuropsychological-and addresses key methodological, empirical, and theoretical issues in this rapidly growing sector of memory research. The papers that follow were presented at a symposium Delaney, 1990; Tulving & Schacter, 1990), it is also pos entitled "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives," held sible to adopt a unitary or single-system view of memory at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society in At and still make use of the implicit/explicit distinction (e.g., lantaonNovember 17,1989. The symposium represents Roediger, Weldon, & Challis, 1989; Witherspoon & something of a milestone, in the sense that if someone Moscovitch, 1989). had suggested organizing an implicit memory symposium The distinction between implicit and explicit memory a decade ago, he or she probably would have been met is also closely related to the distinction between "direct" with a blank stare. That stare would have reflected two and "indirect" tests of memory (Johnson & Hasher, important facts: first, because the term "implicit 1987). -

An Effect of Age on Implicit Memory That Is Not Due to Explicit Contamination

Running head: AN EFFECT OF AGE ON IMPLICIT MEMORY 1 An effect of age on implicit memory that is not due to explicit contamination: Implications for single and multiple-systems theories Emma V. Ward, David R. Shanks, and Christopher, J. Berry University College London Author Note Emma V. Ward, David R. Shanks, and Christopher, J. Berry, Department of Cognitive, Perceptual and Brain Sciences, University College London, England. This research was supported by an ESRC studentship award. We would like to thank Sara Garcia for help with data collection in Experiment 3, and Qizhang Sun for data collection in Experiments 4b and 5. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Emma V. Ward, Department of Cognitive, Perceptual and Brain Sciences, UCL, 26 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AP. E-mail: [email protected] Running head: AN EFFECT OF AGE ON IMPLICIT MEMORY 2 Abstract Implicit memory tests often reveal facilitated processing of previously encountered stimuli even when they cannot be explicitly retrieved. For example, despite decrements in recognition memory, priming in healthy older adults is often comparable in magnitude to that in young individuals. Such observations are commonly taken as evidence for independent explicit and implicit memory systems. On a picture version of the continuous identification with recognition task (CID-R), we found a reliable age-related reduction in recognition memory while the effect on priming did not reach statistical significance (Experiment 1). Experiment 2 replicated these observations using separate priming (CID) and recognition (R) phases. However, when data are combined across experiments to increase power, we find that the reduction in priming reaches statistical significance. -

TRAUMATIC AMNESIA a Dissociative Survival Mechanism

TRAUMATIC AMNESIA a dissociative survival mechanism Dr. Muriel Salmona, psychiatrist, Paris, January 19, 2018 I - Presentation Complete or fragmented traumatic amnesia is a common memory disorder found in victims of violence. Numerous clinical studies have described this well- known phenomenon since the beginning of the twentieth century, when the first systematic studies explored amnesia among traumatized combat soldiers, and later among victims of sexual violence. Studies found almost 40 % complete amnesia among these participants, and 60% partial amnesia when childhood sexual abuse was concerned (Brière 1993, Williams 1994, IVSEA 2015). These amnesias are psychotraumatic consequences of violence. They are neuro- psychological survival mechanisms based on dissociation (Van der Kolk, 1995, 2001). Since 2015, dissociative traumatic amnesias have been recognized as a defining criterium for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (DSM-5, 2015). They can last several decades and lead to amnesia for entire sections of childhood, with almost no retrievable memory, which results in a painful impression of having no past, nor landmarks. When amnesia fades away, traumatic memories most often return brutally, invasively, as uncontrolled, unintegrated, fragmented traumatic memories (flashbacks, nightmares) and trigger re-experiences of violence with identitical distress and sensations, and a vividness as if the trauma was happening all over again. Care professionals should be better acquainted with these phenomena in order to improve how they care for the victims, by treating such reminiscences without confusing them with hallucinations, identifying violence, and its psychotraumatic consequences for the victims. Similarly, justice professionals, when faced with sexual violence complaints after recovered memories, should be more aware of the reality of such frequent memory disorder. -

Rethinking Trauma

How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Daniel Siegel, MD - Main Session - pg. 1 Rethinking Trauma How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma the Main Session with Daniel Siegel, MD and Ruth Buczynski, PhD National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Daniel Siegel, MD - Main Session - pg. 2 Rethinking Trauma: Daniel Siegel, MD How to Use Brain Science to Help Patients Accelerate Healing after Trauma Table of Contents (click to go to a page) How To Define What Happens in the Brain During Trauma ................................... 3 The Optimally Functioning vs. Traumatized Brain as Defined by FACES ................. 4 How Age Affects the Impact of Trauma on the Brain .............................................. 7 Trauma Leads to the Chemical Release of Cortisol and Adrenaline ....................... 8 How Trauma Impairs the Brain’s Memory Systems ............................................... 10 Why the Brain’s Developmental Period Is Crucial to Working with Trauma ............ 11 The Layers of Memory and Encoding Implicit Memory .......................................... 13 The Retrieval of Implicit Memory and the Experience of Flashback ...................... 15 Putting the Science into Clinical Practice ............................................................... 17 What Happens in the Brain during Dissociation? ................................................... 18 -

Interactions Between Attention and Memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne

Interactions between attention and memory Marvin M Chun and Nicholas B Turk-Browne Attention and memory cannot operate without each other. In form of selective attention to internal representations this review, we discuss two lines of recent evidence that [1,2]. support this interdependence. First, memory has a limited capacity, and thus attention determines what will be Classic psychologists such as William James stated long encoded. Division of attention during encoding prevents the ago that ‘we cannot deny that an object once attended to formation of conscious memories, although the role of attention will remain in the memory, while one inattentively in formation of unconscious memories is more complex. Such allowed to pass will leave no traces behind’ [3]. More memories can be encoded even when there is another recently, leading neuroscientists such as Eric Kandel have concurrent task, but the stimuli that are to be encoded must be stated that one of the most important problems for 21st selected from among other competing stimuli. Second, century neuroscience is to understand how attention memory from past experience guides what should be attended. regulates the processes that stabilize experiential mem- Brain areas that are important for memory, such as the ories [4]. Here, we review studies from the past two years hippocampus and medial temporal lobe structures, are that reveal progress towards understanding the inter- recruited in attention tasks, and memory directly affects frontal- actions between attention and memory in neural systems. parietal networks involved in spatial orienting. Thus, exploring the interactions between attention and memory can provide Attention at encoding new insights into these fundamental topics of cognitive A major question in many people’s minds is how to neuroscience. -

Linguistic Communication: Perspectives for Research; Report of the Study Group on Linguistic Communication to the National Institute of Education

i. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 097 622 CS 001 353 AUTHOR Miller, George A., Ed. TITLE Linguistic Communication: Perspectives for Research; Report of the Study Group on Linguistic Communication to the National Institute of Education. INSTITUTION International Reading Association, Newark, Del. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D C PUB DATE 74 NOTE 53p.; Report of a Study Group on Linguistic Communication in Hyannis area of MassachusettsQ August 13-24, 1973 AVAILABLE FROMInternational Reading Association, 800 Barksdale Road, Newark, Delaware 19711 (Stock No. 929, $2.00 nonmember, $1.50 member) EDRS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Communication (Thought Transfer); *Educational Objectives; *Educational Research; Educational Strategies; *Linguistics; Reading Comprehension; Second Languages; Social Influences ABSTRACT This publication, which is divided into three parts, contains the report of a study group of the NationalInstitute of Education which met to investigate some of the problemsof linguistic communication. Part 1 summarizes the general point ofview of the group. Part 2 discussesobjectives, strategies, current status, and time scale. Part 3 describes research activitieswhich cover the social and developmental context with influencesoutside the classroom, characteristics of teachers and classroom,characteristics of the reader, influence on reading of dialectalvariation, and the processes of reading and writing,especially basic literacy, comprehension of language, writing, and second languagelearning. The study group recommends a program of research anddevelopment on learning and instruction in the elements of linguistic communication--reading, writing, listening, speaking--including interactions among these elements. (SW) N.1 S !f. PAP T MI NT OF HEALTH. I01.3( A.1.. hi a WELFARE o.,,s 'Nod NSMUTE OF 1/4.0 t..RfION '.