Zimbabwe.Beef.20190321.Approved V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres Chirumhanzu District Team 1 Ward Centre Dates 18 Mwire primary school 10/06/13-11/06/13 18 Tokwe 4 clinic 12/06/13-13/06/13 18 Chingegomo primary school 14/06/13-15/06/13 16 Chishuku Seondary school 16/06/13-18/06/13 9 Upfumba Secondary school 19/06/13-21/06/13 3 Mutya primary school 22/06/13-24/06/13 2 Gonawapotera secondary school 25/06/13-27/06/13 20 Wildegroove primary school 28/06/13-29/06/13 15 Kushinga primary school 30/06/13-02/07/13 12 Huchu compound 03/07/13-04/-07/13 12 Central estates HQ 5/7/13 20 Mtao/Fair Field compound 6/7/13 12 Chiudza homestead 07/07/13-08/06/13 14 Njerere primary school 9/7/13 Team 2 Ward Centre Dates 22 Hillview Secondary school 10/07/13-12/07/13 17 Lalapanzi Secondary school 13/07/13-15/07/13 16 Makuti homestead 16/06/13-17/06/13 1 Mapiravana Secondary school 18/06/13-19/06/13 9 Siyahukwe Secondary school 20/06/13-23/06/13 4 Chizvinire primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 21 Mukomberana Seconadry school 26/06/13-29/06/13 20 Union primary school 30/06/13-01/07/13 15 Nyikavanhu primary school 02/07/13-03/07/13 19 Musens primary school 04/07/13-06/07/13 16 Utah primary school 07/7/13-09/07/13 Team 3 Ward Centre Dates 11 Faerdan primary school 10/07/13-11/07/13 11 Chamakanda Secondary school 12/07/13-14/07/13 11 Chamakanda primary school 15/07/13-16/07/13 5 Chizhou Secondary school 17/06/13-16/06/13 3 Chilimanzi primary school 21/06/13-23/06/13 25 Maponda primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 6 Holy Cross seconadry school 26/06/13-28/06/13 20 New England Secondary -

For Human Dignity

ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity REPORT ON: APRIL 2020 i DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity For Human Dignity TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. vii ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................................... ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................. xi PART A: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Establishment of the National Inquiry and its Terms of Reference ....................................................... 2 1.2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2: THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ......................................................................................... -

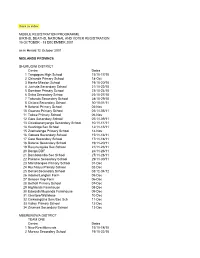

Back to Index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME

Back to index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 15 OCTOBER - 13 DECEMBER 2001 as in Herald 12 October 2001 MIDLANDS PROVINCE SHURUGWI DISTRICT Centre Dates 1 Tongogara High School 15/10-17/10 2 Chironde Primary School 18-Oct 3 Hanke Mission School 19/10-20/10 4 Juchuta Secondary School 21/10-22/10 5 Dombwe Primary School 23/10-24/10 6 Svika Secondary Schoo 25/10-27/10 7 Takunda Secondary School 28/10-29/10 8 Chitora Secondary School 30/10-01/11 9 Batanai Primary School 02-Nov 10 Gwanza Primary School 03/11-05/11 11 Tokwe Primary School 06-Nov 12 Gare Secondary School 07/11-09/11 13 Chivakanenyanga Secondary School 10/11-11/11 14 Kushinga Sec School 12/11-13/11 15 Zvamatenga Primary School 14-Nov 16 Gamwa Secondary School 15/11-16/11 17 Gato Secondary School 17/11-18/11 18 Batanai Secondary School 19/11-20/11 19 Rusununguko Sec School 21/11-23/11 20 Donga DDF 24/11-26/11 21 Dombotombo Sec School 27/11-28/11 22 Pakame Secondary School 29/11-30/11 23 Marishongwe Primary School 01-Dec 24 Ruchanyu Primary School 02-Dec 25 Dorset Secondary School 03/12-04/12 26 Adams/Longton Farm 05-Dec 27 Beacon Kop Farm 06-Dec 28 Bethall Primary School 07-Dec 29 Highlands Farmhouse 08-Dec 30 Edwards/Muponda Farmhouse 09-Dec 31 Glentore/Wallclose 10-Dec 32 Chikwingizha Sem/Sec Sch 11-Dec 33 Valley Primary School 12-Dec 34 Zvumwa Secondary School 13-Dec MBERENGWA DISTRICT TEAM ONE Centre Dates 1 New Resettlements 15/10-18/10 2 Murezu Secondary School 19/10-22/10 3 Chizungu Secondary School 23/10-26/10 4 Matobo Secondary -

Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program June 2015 – September 2016

Annual Report #1 Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program June 2015 – September 2016 Feed the Future Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program | Annual Report #1 Fintrac Inc. www.fintrac.com [email protected] US Virgin Islands 3077 Kronprindsens Gade 72 St. Thomas, USVI 00802 Tel: (340) 776-7600 Fax: (340) 776-7601 Washington, DC 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20036 USA Tel: (202) 462-8475 Fax: (202) 462-8478 Feed the Future Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program (FTFZ-LD) 5 Premium Close Mt. Pleasant Business Park Mt. Pleasant, Harare Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 338964-69 [email protected] www.fintrac.com All Photos by Fintrac October 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by Fintrac Inc. under contract AID-613-C-15-00001 with USAID/Zimbabwe. Prepared by Fintrac Inc. Feed the Future Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program | Annual Report #1 CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................... III 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 1 2. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES .................................................................................. 5 3. ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Beneficiaries ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

Zimbabwe Page 1 of 35

Zimbabwe Page 1 of 35 Zimbabwe Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2001 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 4, 2002 Zimbabwe is a republic in which President Robert Mugabe and his Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) have dominated the executive and legislative branches of the Government since independence in 1980. Although the Constitution allows for multiple parties, opposition parties and their supporters were subjected to significant intimidation and violence by the ruling party and government security forces, and financial restrictions continued to be imposed on the opposition. The 2000 parliamentary elections were preceded by a government-sanctioned campaign of violence directed towards supporters and potential supporters of the opposition. Although most election observers agreed that the voting process itself generally was peaceful, there were irregularities. In 1999 the country's first viable opposition party emerged, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which won 57 out of 120 seats in the June 2000 parliamentary elections. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary, and in practice the judiciary remained largely independent despite government attempts to dilute its independence; however, the Government repeatedly refused to abide by judicial decisions. The Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) is responsible for maintaining law and order. Although the ZRP officially is under the authority of the Ministry of Home Affairs, in practice it is controlled by the President's office. The Zimbabwe National Army and Air Force under the Defense Ministry are responsible for external security; however, they frequently were called upon for domestic operations during the year. The Central Intelligence Organization (CIO), under the Minister of State for National Security in the President's Office, is responsible for internal and external security, but it does not have powers of arrest. -

Zimconsult Independent Economic & Planning Consultants

Zimconsult Independent economic & planning consultants FAMINE IN ZIMBABWE Famine in Zimbabwe Implications of 2003/04 Cropping season Prepared for the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung April 2004 ii Famine in Zimbabwe Implications of 2003/04 Cropping season CONTENTS Acronyms………………………………………………………………………...…ii 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................1 2. METHODOLOGY........................................................................................1 3. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS..........................................................................2 3.1 Demand..............................................................................................................2 3.2 Production..........................................................................................................3 3.3 Urban Maize.......................................................................................................3 4. FACTORS DETERMINING FOOD PRODUCTION ....................................4 4.1 Maize Seed .......................................................................................................4 4.2 Shortage of Fertilizers.......................................................................................5 4.3 Tillage................................................................................................................6 4.4 Rainfall ..............................................................................................................6 4.5 Combined Effects of the -

Climate Change, Pesticides and Health: Considering the Risks and Opportunities of Adaptation for Zimbabwean Smallholder Cotton Growers

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Climate Change, Pesticides and Health: Considering the Risks and Opportunities of Adaptation for Zimbabwean Smallholder Cotton Growers Cliff Zinyemba 1 , Emma Archer 2 and Hanna-Andrea Rother 1,* 1 Division of Environmental Health, and Centre for Environmental and Occupational Health Research, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, Observatory, Cape Town 7925, South Africa; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Geoinformatics and Meteorology, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield 0028, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: There is potential for increased pesticide-related adverse health outcomes in the agricultural sector linked to adaptive increases in pesticide use necessitated, in part, by climate change-related increases in pest populations. To understand the role of adaptation practices in pesticide use and health risks, this study assessed Zimbabwean smallholder cotton farmers’ adaptive responses linked to their climate change perceptions. In depth interviews were conducted with 50 farmers who had been growing cotton for at least 30 years. The study identified farmers’ adaptation practices that increased their pesticide use, as well as those that presented opportunities for reducing pesticide use through non-pesticide-dependent adaptation pathways. The findings show that due to perceived climate change impacts, such as a shorter growing season, farmers were adopting a range of adaptive practices. These included changes in pest management practices, such as increasing pesticide spraying frequencies due to keeping ratoon crops, which were increasing farmers’ overall pesticide use. Such incremental adaptive practices are potentially maladaptive, as they may increase farmers’ pesticide- Citation: Zinyemba, C.; Archer, E.; related health risks. -

Revised HSS Annual Report 2013

ZIM-809-G14-S HEALTH SYSTEMS STRENGTHENING CROSS- CUTTING INTERVENTIONS Annual Report 2013 15 April 2014 TABLE CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 2 OVERVIEW OF THE GRANT ........................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 COMPONENTS OF THE GRANT ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2.1 Health Retention Scheme ................................................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.2 Community Systems Strengthening (CSS) ................................................................................................................ 4 2.2.3 Health information Systems (HIS) ................................................................................................................................. 4 2.3 COORDINATION OF THE GRANT ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 ACTIVITIES IMPLEMENTED .......................................................................................................................... -

Mobile Registration Programme Births, Deaths, National and Voter Registration 1St May, 2004 to 30Th June 2004

MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 1ST MAY, 2004 TO 30TH JUNE 2004 Back MIDLANDS PROVINCE CHIRUMANZI DISTRICT TEAM 1 CENTRE DATES 1.Mutenderende Secondary School 01/05/04-05/05/04 2.Chengwena Business Centre 07/05/04-12/05/04 3.Charandura Council Hall 13/05/04-18/05/04 4.Upfumba Secondary School 19/05/04-24/05/04 5.Siyahokwe Govt School 25/05/04-30/05/04 6.Holly Cross Secondary 31/05/04-05/06/04 7.Mukomberwana Secondary School 06/06/04-11/06/04 8.Gonawapotera Secondary School 12/06/04-17/06/04 9.Chizhou Secondary School 18/06/04-23/06/04 10.Mapiravana Secondary School 24/06/04-30/06/04 TEAM 2 CENTRE DATES 1.Lynwood Centre 01/05/04-03/05/04 2.Nemesis Primary School 04/05/04-06/05/04 3.Beacon Hill Homestead 07/05/04-09/05/04 4.Tokwe 4 Clinic 10/05/04-12/05/04 5.Lalapanzi Clinic 13/05/04-18/05/04 6.Makuti Ranch Farmhouse 19/05/04-21/05/04 7.Mahamara-Kensey Compound 22/05/04-24/05/04 8.Utah Ranch Homestaed 25/05/04-27/05/04 9.Chiodza Homestead 28/05/04-30/05/04 10.Central Estates HQ 31/05/04-02/06/04 11.Driefontein Mission 03/06/04-05/06/04 12.Welstead Farmhouse 06/06/04-08/06/04 13.Zivagwe School Ortons Drift 09/06/04-11/06/04 14.Classen-Manyora Homestead 12/06/04-14/06/04 15. -

Women's Participation in Mining

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 7, Ver. VII (July 2015), PP 99-104 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A step into the male dominated mining sector: Women’s participation in mining: the case of Kwekwe District, Zimbabwe. Elizabeth F. Hove1, James Hlongwana2, 1Department of English and Performing Arts, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe 2Department of History & Development Studies, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe Abstract: Zimbabwe’s determination to empower its citizens is loud and clear and the policy is rooted in distributive justice. This has resulted in people-oriented policies being implemented in various sectors including the mining industry. The consequence has been a significant penetration and control of the small scale mining sector by Africans. However, the affirmative action has somehow missed a target. It has tended to empower men alone than women resulting in serious economic and social gender inequality in the society. The paper analyses the contribution of gender neutral mining cooperatives to the empowerment of women in the society. As both women and men possess inherent skills and weaknesses gender inclusive syndicates will ensure optimum utilisation of their individual skills. The resultant exploitation of gendered skills will place women and men on an equal footing in production and development. Thus development will cease being a male-driven process but a game of all people in the society. The paper argues that gender-neutral mining cooperatives will promote social and economic visibility of women in the society and ultimately enhance gender equality in resource ownership and utilisation. -

Social Policy Outcomes of Zimbabwe’S Fast Track Land Reform

SOCIAL POLICY OUTCOMES OF ZIMBABWE’S FAST TRACK LAND REFORM PROGRAM (FTLRP): A CASE STUDY OF KWEKWE DISTRICT By MUSAVENGANA WINSTON THEODORE CHIBWANA Submitted in accordance with the requirements For the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY In the subject DEVELOPMENT STUDIES At the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR JIMI O. ADESINA NOVEMBER 2016 i The poor are not poor because they are poor but because they are socially deprived, that is, they can help themselves if someone somewhere in society can help them to do so. Archie Mafeje (2003) ii Student Number: 53318218 I declare that SOCIAL POLICY OUTCOMES OF ZIMBABWE’S FAST TRACK LAND REFORM PROGRAM (FTLRP): A CASE STUDY OF KWEKWE DISTRICT is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. Signed: Date: Musavengana W.T. Chibwana 21/11/2016 This thesis is being submitted for examination with my approval. Signed: Date: Supervisor: Professor Jimi Adesina 21 November, 2016 iii DEDICATION To ‘Dr. Winston’, An inscription that was curved on stones of the plains of Chiundura As I was herding my grandfather’s cattle When I was young and pregnant of colossal aspiration. iv ABSTRACT Social policy outcomes of Zimbabwe’s Fast Track Land Reform Program (FTLRP): A case study of Kwekwe District This thesis explores social policy outcomes of the FTLRP. The thesis comes from an appreciation that there has been a lot of attention that has been given to the process and outcomes of the FTLRP. Various and sometimes antagonistic analytical frameworks have been employed by different scholars who come from different epistemological standings resulting in academic polarity on the subject of the FTLRP in Zimbabwe.