Women's Participation in Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres Chirumhanzu District Team 1 Ward Centre Dates 18 Mwire primary school 10/06/13-11/06/13 18 Tokwe 4 clinic 12/06/13-13/06/13 18 Chingegomo primary school 14/06/13-15/06/13 16 Chishuku Seondary school 16/06/13-18/06/13 9 Upfumba Secondary school 19/06/13-21/06/13 3 Mutya primary school 22/06/13-24/06/13 2 Gonawapotera secondary school 25/06/13-27/06/13 20 Wildegroove primary school 28/06/13-29/06/13 15 Kushinga primary school 30/06/13-02/07/13 12 Huchu compound 03/07/13-04/-07/13 12 Central estates HQ 5/7/13 20 Mtao/Fair Field compound 6/7/13 12 Chiudza homestead 07/07/13-08/06/13 14 Njerere primary school 9/7/13 Team 2 Ward Centre Dates 22 Hillview Secondary school 10/07/13-12/07/13 17 Lalapanzi Secondary school 13/07/13-15/07/13 16 Makuti homestead 16/06/13-17/06/13 1 Mapiravana Secondary school 18/06/13-19/06/13 9 Siyahukwe Secondary school 20/06/13-23/06/13 4 Chizvinire primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 21 Mukomberana Seconadry school 26/06/13-29/06/13 20 Union primary school 30/06/13-01/07/13 15 Nyikavanhu primary school 02/07/13-03/07/13 19 Musens primary school 04/07/13-06/07/13 16 Utah primary school 07/7/13-09/07/13 Team 3 Ward Centre Dates 11 Faerdan primary school 10/07/13-11/07/13 11 Chamakanda Secondary school 12/07/13-14/07/13 11 Chamakanda primary school 15/07/13-16/07/13 5 Chizhou Secondary school 17/06/13-16/06/13 3 Chilimanzi primary school 21/06/13-23/06/13 25 Maponda primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 6 Holy Cross seconadry school 26/06/13-28/06/13 20 New England Secondary -

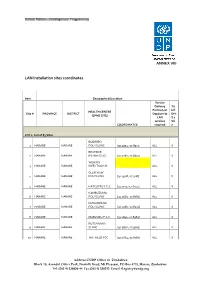

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

The Undersigned Authenticate That the the Midlands State University for Assessing Zimbabwean Local Housing: Challenges and Oppor

APPROVAL FORM The undersigned authenticate that they have supervised and recommended to the Midlands State University for acceptance the dissertation entitled: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Of Kwekwe City Council. Submitted by :Christiner Mjanga Reg. No. R134524H in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Sciences Honours Degree in Local Governance Studies. ..................................................... ...................................................... SUPERVISIOR DATE .................................................... ........................................................ CHAIRPERSON DATE i FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE RELEASE FORM Name of Student: Christiner Mjanga Registration Number: R134524H Dissertation title: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing- Challenges and Opportunities: Case of Kwekwe City Council. Degree to which Dissertation was presented: Bsc Honours in Local governance studies Year this degree granted: 2016 Permission is hereby granted to the Midlands State University library to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research only. The author reserves other publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author`s written permission. Signed ...................................................... -

VII. the Unity Government Response

HUMAN RIGHTS THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections WATCH The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... ii I. Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

For Human Dignity

ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity REPORT ON: APRIL 2020 i DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity For Human Dignity TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. vii ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................................... ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................. xi PART A: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Establishment of the National Inquiry and its Terms of Reference ....................................................... 2 1.2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2: THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ......................................................................................... -

Zimbabwe.Beef.20190321.Approved V2

Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D) is a tool funded by the European Commission / DEVCO and is implemented in partnership with Agrinatura. Agrinatura (http://agrinatura-eu.eu) is the European AllianCe of Universities and Research Centers involved in agricultural researCh and CapaCity building for development. The information and knowledge produCed through the value Chain studies are intended to support the Delegations of the European Union and their partners in improving poliCy dialogue, investing in value Chains and better understanding the Changes linked to their aCtions VCA4D uses a systematiC methodologiCal framework for analysing value Chains in agriCulture, livestoCk, fishery, aquaCulture and agroforestry. More information inCluding reports and communication material Can be found at: https://europa.eu/CapaCity4dev/value-chain-analysis-for- development-vca4d- Team Composition Ben Bennett, Team Leader and eConomist (NRI) Muriel Figué, social expert (CIRAD) Mathieu Vigne, environmental expert (CIRAD) Charles Chakoma, national consultant (independent) Pamela KatiC, support to economist (NRI) The report was produCed through the finanCial support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of its authors and does not neCessarily refleCt the views of the European Union. The report has been realised within a projeCt finanCed by the European Union (VCA4D CTR 2016/375-804). Citation of this report: Bennett, B., Chakoma, C., Figué, M, Vigne, M., KatiC, P.; 2019. Beef Value Chain Analysis in Zimbabwe. Report for the -

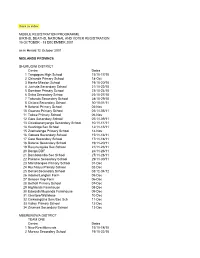

Back to Index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME

Back to index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 15 OCTOBER - 13 DECEMBER 2001 as in Herald 12 October 2001 MIDLANDS PROVINCE SHURUGWI DISTRICT Centre Dates 1 Tongogara High School 15/10-17/10 2 Chironde Primary School 18-Oct 3 Hanke Mission School 19/10-20/10 4 Juchuta Secondary School 21/10-22/10 5 Dombwe Primary School 23/10-24/10 6 Svika Secondary Schoo 25/10-27/10 7 Takunda Secondary School 28/10-29/10 8 Chitora Secondary School 30/10-01/11 9 Batanai Primary School 02-Nov 10 Gwanza Primary School 03/11-05/11 11 Tokwe Primary School 06-Nov 12 Gare Secondary School 07/11-09/11 13 Chivakanenyanga Secondary School 10/11-11/11 14 Kushinga Sec School 12/11-13/11 15 Zvamatenga Primary School 14-Nov 16 Gamwa Secondary School 15/11-16/11 17 Gato Secondary School 17/11-18/11 18 Batanai Secondary School 19/11-20/11 19 Rusununguko Sec School 21/11-23/11 20 Donga DDF 24/11-26/11 21 Dombotombo Sec School 27/11-28/11 22 Pakame Secondary School 29/11-30/11 23 Marishongwe Primary School 01-Dec 24 Ruchanyu Primary School 02-Dec 25 Dorset Secondary School 03/12-04/12 26 Adams/Longton Farm 05-Dec 27 Beacon Kop Farm 06-Dec 28 Bethall Primary School 07-Dec 29 Highlands Farmhouse 08-Dec 30 Edwards/Muponda Farmhouse 09-Dec 31 Glentore/Wallclose 10-Dec 32 Chikwingizha Sem/Sec Sch 11-Dec 33 Valley Primary School 12-Dec 34 Zvumwa Secondary School 13-Dec MBERENGWA DISTRICT TEAM ONE Centre Dates 1 New Resettlements 15/10-18/10 2 Murezu Secondary School 19/10-22/10 3 Chizungu Secondary School 23/10-26/10 4 Matobo Secondary -

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA LYNWOOD CENTER TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHENGWENA RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE, CHIEF HAMA CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU VILLAGE 2A CHISHUKU RESETLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIVONA DENHERE VILLAGE WARD 3 MHENDE CMZ Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA VILLAGE 38 CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZHOU WARD 5 MUZEZA VILLAGE, HEADMAN BANGURE , CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DANNY DANNY SEC Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DRIEFONTEIN DRIEFONTEIN MISSION FARM Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu GONAWAPOTERA CHAKA BUSINESS CENTRE MVUMA MASVINGO ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HILLVIEW HILLVIEW VILLAGE1, LALAPANZI Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HOLY CROSS HOLY CROSS MISSION WARD 6 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LALAPANZI 42KM ALONG GWERU-MVUMA ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA 2KM ALONG CENTRAL ESTATES ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MAPIRAVANA MAPIRAVANA VILLAGE WARD 1CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUKOMBERANWA MUWANI VILLAGE HEADMAN MANHOVO Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSENA VILLAGE 8 MUSENA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSHANDIRAPAMWE RUDHUMA VILLAGE WARD 25 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUTENDERENDE DZORO VILLAGE CHIEF HAMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu NEW ENGLAND LOVEDALE FARMSUB-DIVISION 2 MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu ORTON'S DRIFT ORTON'S DRIFT FARM Secondary Midlands -

Midlands North Inspection Stations

MIDLANDS NORTH INSPECTION STATIONS GOKWE CENTRAL 1 BHEJANI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHEVECHEVE SECONDARY SCHOOL 3 CHIDAMOYO PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIDOMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 CHITAPO BUSINESS CENTRE 6 GANYUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 GWANYIKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 GWENUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GWENYA PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 JAHANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 KASIKANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 KRIMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 MALIYAMI PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 MAPU PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 MTANKI PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 MUTANGE C.B. PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 MWEMBESI PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 NDABAMBI PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 NHONGO PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 SATENGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 SENGWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 SIMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 ST. CUTHBERTS MASORO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 TONGWE SECONDARY SCHOOL 25 CHIZIYA COMMUNITY HALL 26 GABABE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 RAJI MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT 28 GWEHAVA PRIMARY SCHOOL GOKWE EAST 1 BATSIRAI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHAMINUKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 3 CHINYENYETU PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIODZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 COPPER QUEEN BUSINESS CENTRE 6 DENDA PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 DEWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 DINDIMUTIWI PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GANDAVACHE PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 GOREDEMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 GWEBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 HWADZE PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 KAHOBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 KAMWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 KAMWAMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 KASONDE PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 KUEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 KWAEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 MADZIDRIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 MASOSONI PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 MHUMHA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 MSADZI PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 MUDONDO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 MUPAWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 25 MUSOROWENZOU PRIMARY SCHOOL 26 MUTEHWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 MUTUKANYI PRIMARY SCHOOL 28 NORAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 29 NYAMAZENGWE PRIMARY -

Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program June 2015 – September 2016

Annual Report #1 Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program June 2015 – September 2016 Feed the Future Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program | Annual Report #1 Fintrac Inc. www.fintrac.com [email protected] US Virgin Islands 3077 Kronprindsens Gade 72 St. Thomas, USVI 00802 Tel: (340) 776-7600 Fax: (340) 776-7601 Washington, DC 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20036 USA Tel: (202) 462-8475 Fax: (202) 462-8478 Feed the Future Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program (FTFZ-LD) 5 Premium Close Mt. Pleasant Business Park Mt. Pleasant, Harare Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 338964-69 [email protected] www.fintrac.com All Photos by Fintrac October 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by Fintrac Inc. under contract AID-613-C-15-00001 with USAID/Zimbabwe. Prepared by Fintrac Inc. Feed the Future Zimbabwe Livestock Development Program | Annual Report #1 CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................... III 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 1 2. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES .................................................................................. 5 3. ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Beneficiaries ......................................................................................................................................................... -

The Struggle for Democracy in the Political Minefield of Zimbabwe

THE STRUGGLE FOR DEMOCRACY IN THE POLITICAL MINEFIELD OF ZIMBABWE A STORY OF THE POLITICAL VIOLENCE EXPERIENCED BY BLESSING CHEBUNDO, MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT, KWEKWE MOVEMENT FOR DEMOCRATIC CHANGE, ZIMBABWE Julius Caesar wrote: “I came, I saw, I conquered”. And I say: “I entered the Zimbabwe Political arena, I fight for Democracy, I will continue the struggle”. My story starts with the Zimbabwe Constitutional Referendum, held on the 12th February 2000, which saw President Robert Mugabe’s Zanu PF getting its first national defeat in the Political Arena and thereby setting the tone for Zimbabwe’s political violence. Sensing danger of a political whitewash by the newly formed MDC, Zanu PF gathered all its violent political might to crush the young MDC Party and its supporters. By voting against the changes in the Zimbabwe Constitutional Referendum, the people of Zimbabwe had taken heed of the call by the combined efforts of the MDC and the National Constitutional Assembly (NCA) and had demonstrated their intolerance to the misrule of the prior 20 years by Zanu PF. As is 1 already known, the first targets were the white commercial farmers, their workers and the MDC activists. The whirlwind of political violence began with an opening bang in February 2000!! I had worked with Paul Themba Nyathi both under the NCA and since the inception of the MDC, during the peoples pre-convention. Pre-convention is the period for intensive coordination of Civic Society organisations leading to the birth of the MDC. Paul was a member of the MDC’s interim National Executive Committee (NEC), whilst I was the Interim Provincial Chairman for Midlands North.