`` Faculty of Arts Department of History the Rise and Fall of the Mining Industry in Zimbabwe with Particular Reference To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

Turmoil in Zimbabwe's Mining Sector

All That Glitters is Not Gold: Turmoil in Zimbabwe’s Mining Sector Africa Report N°294 | 24 November 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Makings of an Unstable System ................................................................................ 5 A. Pitfalls of a Single Gold Buyer ................................................................................... 5 B. Gold and Zimbabwe’s Patronage Economy ............................................................... 7 C. A Compromised Legal and Justice System ................................................................ 10 III. The Bitter Fruits of Instability .......................................................................................... 14 A. A Spike in Machete Gang Violence ............................................................................ 14 B. Mounting Pressure on the Mnangagwa Government ............................................... 15 C. A Large-scale Police Operation .................................................................................. 16 IV. Three Mines, Three Stories of Violence .......................................................................... -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

The Undersigned Authenticate That the the Midlands State University for Assessing Zimbabwean Local Housing: Challenges and Oppor

APPROVAL FORM The undersigned authenticate that they have supervised and recommended to the Midlands State University for acceptance the dissertation entitled: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Of Kwekwe City Council. Submitted by :Christiner Mjanga Reg. No. R134524H in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Sciences Honours Degree in Local Governance Studies. ..................................................... ...................................................... SUPERVISIOR DATE .................................................... ........................................................ CHAIRPERSON DATE i FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE RELEASE FORM Name of Student: Christiner Mjanga Registration Number: R134524H Dissertation title: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing- Challenges and Opportunities: Case of Kwekwe City Council. Degree to which Dissertation was presented: Bsc Honours in Local governance studies Year this degree granted: 2016 Permission is hereby granted to the Midlands State University library to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research only. The author reserves other publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author`s written permission. Signed ...................................................... -

VII. the Unity Government Response

HUMAN RIGHTS THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections WATCH The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... ii I. Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA LYNWOOD CENTER TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHENGWENA RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE, CHIEF HAMA CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU VILLAGE 2A CHISHUKU RESETLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIVONA DENHERE VILLAGE WARD 3 MHENDE CMZ Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA VILLAGE 38 CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZHOU WARD 5 MUZEZA VILLAGE, HEADMAN BANGURE , CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DANNY DANNY SEC Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DRIEFONTEIN DRIEFONTEIN MISSION FARM Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu GONAWAPOTERA CHAKA BUSINESS CENTRE MVUMA MASVINGO ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HILLVIEW HILLVIEW VILLAGE1, LALAPANZI Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HOLY CROSS HOLY CROSS MISSION WARD 6 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LALAPANZI 42KM ALONG GWERU-MVUMA ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA 2KM ALONG CENTRAL ESTATES ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MAPIRAVANA MAPIRAVANA VILLAGE WARD 1CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUKOMBERANWA MUWANI VILLAGE HEADMAN MANHOVO Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSENA VILLAGE 8 MUSENA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSHANDIRAPAMWE RUDHUMA VILLAGE WARD 25 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUTENDERENDE DZORO VILLAGE CHIEF HAMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu NEW ENGLAND LOVEDALE FARMSUB-DIVISION 2 MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu ORTON'S DRIFT ORTON'S DRIFT FARM Secondary Midlands -

Midlands North Inspection Stations

MIDLANDS NORTH INSPECTION STATIONS GOKWE CENTRAL 1 BHEJANI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHEVECHEVE SECONDARY SCHOOL 3 CHIDAMOYO PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIDOMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 CHITAPO BUSINESS CENTRE 6 GANYUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 GWANYIKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 GWENUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GWENYA PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 JAHANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 KASIKANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 KRIMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 MALIYAMI PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 MAPU PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 MTANKI PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 MUTANGE C.B. PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 MWEMBESI PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 NDABAMBI PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 NHONGO PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 SATENGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 SENGWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 SIMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 ST. CUTHBERTS MASORO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 TONGWE SECONDARY SCHOOL 25 CHIZIYA COMMUNITY HALL 26 GABABE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 RAJI MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT 28 GWEHAVA PRIMARY SCHOOL GOKWE EAST 1 BATSIRAI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHAMINUKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 3 CHINYENYETU PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIODZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 COPPER QUEEN BUSINESS CENTRE 6 DENDA PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 DEWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 DINDIMUTIWI PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GANDAVACHE PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 GOREDEMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 GWEBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 HWADZE PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 KAHOBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 KAMWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 KAMWAMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 KASONDE PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 KUEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 KWAEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 MADZIDRIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 MASOSONI PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 MHUMHA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 MSADZI PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 MUDONDO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 MUPAWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 25 MUSOROWENZOU PRIMARY SCHOOL 26 MUTEHWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 MUTUKANYI PRIMARY SCHOOL 28 NORAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 29 NYAMAZENGWE PRIMARY -

Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012

Zimbabwe Provincial Report Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012 Population Census Office P.O. Box CY342 Causeway Harare Tel: 04-793971-2 04-794756 E-mail: [email protected] Census Results for Midlands Province at a Glance Population Size Total 1 614 941 Males 776 787 Females 838 154 Annual Average Increase (Growth Rate) 2.2 Average Household Size 4.5 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................3 List of Tables.....................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................9 Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................10 Midlands Fact Sheet (Final Results) .................................................................................................13 Chapter 1: ........................................................................................................................................14 Population Size and Structure .......................................................................................................14 Chapter 2: ........................................................................................................................................24 Population Distribution -

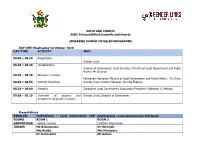

Local Government Summit Programme

VOICE AND CHOICE: SADC Protocol@Work Summits and Awards ZIMBABWE SUMMIT DETAILED PROGRAMME DAY ONE: Wednesday 14 October 2020 DAY/TIME ACTIVITY WHO 08.00 – 08.20 Registration Gender Links 08.20 – 08.30 Introductions: Director of Ceremonies: Chief Directors: Ministry of Local Government and Public Works: Mr Shumba 08.30 – 08.40 Welcome remarks: Permanent Secretary Ministry of Local Government and Public Works: Mr Churu 08.40 – 08.50 Summit objectives Gender Links Country Manager- Priscilla Maposa 08.50 – 09:00 Remarks Zimbabwe Local Government Association President- Alderman G. Mutasa 09.00 – 09.10 Overview of process and Gender Links/ Director of Ceremonies assignment of parallel sessions Presentations PARALLEL Institutional – Local Government COE Institutional – Local Government COE Rural ROOMSSESSIONS ROOMUrban 1 ROOM 2 RAPPORTEUR Tapiwa Zvaraya Cuthbert Mapuranga JUDGES Ms Butaumocho Dr Chirundu Mrs Ncube Mrs Nhandara Dr Jeranyama Mr Gotora PARALLEL Institutional – Local Government COE Institutional – Local Government COE Rural PresentationsSESSIONS Urban 09.10 – 09.30 1. Bulawayo City Council 1. Buhera RDC 09.30 – 09.50 2. Harare City Council 2. Goromonzi RDC 09.50 – 10.10 3. Beitbridge Town Council 3. Guruve RDC 10.10 – 10.30 4. Bindura Municipality 4. Gutu RDC 10.30 – 10.50 5. Chiredzi Town Council 5. Manyame RDC 10.50 – 11.20 TEA 11.20 – 11.40 6. Epworth Local Board 6. Mazowe RDC 11.40 – 12.00 7. Gokwe Town Council 7. Murehwa RDC 12.00 – 12.20 8. Gwanda Municipality 8. Mutoko RDC 12.20 – 12.40 9. Gweru City Council 9. Nyanga RDC 12.40 – 13.00 10. -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

Zimbabwe (Country Code +263) Communication of 12.XII.2018

Zimbabwe (country code +263) Communication of 12.XII.2018: The Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ), Harare, announces updates to the national numbering plan of Zimbabwe. POTRAZ has approved the amendment and consolidation of National Geographical Area Codes on the Public Switched Telephone Network in Zimbabwe by TelOne (Pvt) Limited. POTRAZ has also assigned new subscriber number block of 078 6 XXX XXX and 078 7 XXX XXX to Econet Wireless Zimbabwe. The updated national numbering plan of Zimbabwe is as follows. 1. Definitions Country Code (CC) Country Code (CC) is a digit or a combination of digits (one, two or three) identifying a specific country or countries. Dialling Plan A string or combination of decimal digits, symbols, that defines the method by which the numbering plan is used. A dialling plan includes the use of prefixes, suffixes, and additional information, supplementary to the numbering plan, required to complete the call. Geographic Area Code or Area Code (AC) This refers to an area code that has a defined geographic boundary. Geographic area codes are for conventional fixed- line (or land line) services terminating at fixed points. The Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) is divided into several geographic areas. Each of the geographic area is allocated an area code. International Access Prefix (IAP) A digit or combination of digits used to indicate that the number following is an international directory number. In Zimbabwe the International Dialling Access Prefix is ‘00’. National Access Prefix (NAP) or Trunk Prefix A digit or combination of digits used by a calling subscriber to make a call to another subscriber in his own country, but outside his own numbering area or network.