Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres Chirumhanzu District Team 1 Ward Centre Dates 18 Mwire primary school 10/06/13-11/06/13 18 Tokwe 4 clinic 12/06/13-13/06/13 18 Chingegomo primary school 14/06/13-15/06/13 16 Chishuku Seondary school 16/06/13-18/06/13 9 Upfumba Secondary school 19/06/13-21/06/13 3 Mutya primary school 22/06/13-24/06/13 2 Gonawapotera secondary school 25/06/13-27/06/13 20 Wildegroove primary school 28/06/13-29/06/13 15 Kushinga primary school 30/06/13-02/07/13 12 Huchu compound 03/07/13-04/-07/13 12 Central estates HQ 5/7/13 20 Mtao/Fair Field compound 6/7/13 12 Chiudza homestead 07/07/13-08/06/13 14 Njerere primary school 9/7/13 Team 2 Ward Centre Dates 22 Hillview Secondary school 10/07/13-12/07/13 17 Lalapanzi Secondary school 13/07/13-15/07/13 16 Makuti homestead 16/06/13-17/06/13 1 Mapiravana Secondary school 18/06/13-19/06/13 9 Siyahukwe Secondary school 20/06/13-23/06/13 4 Chizvinire primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 21 Mukomberana Seconadry school 26/06/13-29/06/13 20 Union primary school 30/06/13-01/07/13 15 Nyikavanhu primary school 02/07/13-03/07/13 19 Musens primary school 04/07/13-06/07/13 16 Utah primary school 07/7/13-09/07/13 Team 3 Ward Centre Dates 11 Faerdan primary school 10/07/13-11/07/13 11 Chamakanda Secondary school 12/07/13-14/07/13 11 Chamakanda primary school 15/07/13-16/07/13 5 Chizhou Secondary school 17/06/13-16/06/13 3 Chilimanzi primary school 21/06/13-23/06/13 25 Maponda primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 6 Holy Cross seconadry school 26/06/13-28/06/13 20 New England Secondary -

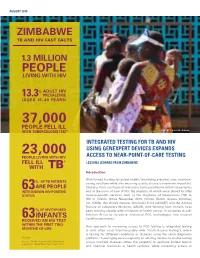

Integrated Testing for TB and HIV Zimbabwe

AUGUST 2019 ZIMBABWE TB AND HIV FAST FACTS 1.3 MILLION PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV % ADULT HIV 13.3 PREVALENCE (AGES 15–49 YEARS) 37,000 PEOPLE FELL ILL WITH TUBERCULOSIS (TB)* © UNICEF/Costa/Zimbabwe INTEGRATED TESTING FOR TB AND HIV 23,000 USING GENEXPERT DEVICES EXPANDS PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV ACCESS TO NEAR-POINT-OF-CARE TESTING FELL ILL * LESSONS LEARNED FROM ZIMBABWE WITH TB Introduction With limited funding for global health, identifying practical, cost- and time- OF TB PATIENTS % saving solutions while also ensuring quality of care is evermore important. 63ARE PEOPLE Globally, there are fleets of molecular testing platforms within laboratories WITH KNOWN HIV-POSITIVE and at the point of care (POC), the majority of which were placed to offer STATUS disease-specific services such as the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) or HIV in infants. Since November 2015, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Inc. (CHAI), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), with funding from Unitaid, have % OF HIV-EXPOSED been working closely with ministries of health across 10 countries in sub- Saharan Africa to introduce innovative POC technologies into national INFANTS 1 63 health programmes. RECEIVED AN HIV TEST WITHIN THE FIRST TWO One approach to increasing access to POC testing is integrated testing MONTHS OF LIFE (a term often used interchangeably with “multi-disease testing”), which is testing for different conditions or diseases using the same diagnostic *Annually platform.2 Leveraging excess capacity on existing devices to enable testing Sources: UNAIDS estimates 2019; World Health across multiple diseases offers the potential to optimize limited human Organization, ‘Global Tuberculosis Report 2018’ and financial resources at health facilities, while increasing access to rapid testing services. -

An Analysis of Primary and Secondary Production in Lake Kariba in a Changing Climate

AN ANALYSIS OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY PRODUCTION IN LAKE KARIBA IN A CHANGING CLIMATE MZIME R. NDEBELE-MURISA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Philosophiae in the Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof. Charles Musil Co-Supervisor: Prof. Lincoln Raitt May 2011 An analysis of primary and secondary production in Lake Kariba in a changing climate Mzime Regina Ndebele-Murisa KEYWORDS Climate warming Limnology Primary production Phytoplankton Zooplankton Kapenta production Lake Kariba i Abstract Title: An analysis of primary and secondary production in Lake Kariba in a changing climate M.R. Ndebele-Murisa PhD, Biodiversity and Conservation Biology Department, University of the Western Cape Analysis of temperature, rainfall and evaporation records over a 44-year period spanning the years 1964 to 2008 indicates changes in the climate around Lake Kariba. Mean annual temperatures have increased by approximately 1.5oC, and pan evaporation rates by about 25%, with rainfall having declined by an average of 27.1 mm since 1964 at an average rate of 6.3 mm per decade. At the same time, lake water temperatures, evaporation rates, and water loss from the lake have increased, which have adversely affected lake water levels, nutrient and thermal dynamics. The most prominent influence of the changing climate on Lake Kariba has been a reduction in the lake water levels, averaging 9.5 m over the past two decades. These are associated with increased warming, reduced rainfall and diminished water and therefore nutrient inflow into the lake. The warmer climate has increased temperatures in the upper layers of lake water, the epilimnion, by an overall average of 1.9°C between 1965 and 2009. -

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

Turmoil in Zimbabwe's Mining Sector

All That Glitters is Not Gold: Turmoil in Zimbabwe’s Mining Sector Africa Report N°294 | 24 November 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Makings of an Unstable System ................................................................................ 5 A. Pitfalls of a Single Gold Buyer ................................................................................... 5 B. Gold and Zimbabwe’s Patronage Economy ............................................................... 7 C. A Compromised Legal and Justice System ................................................................ 10 III. The Bitter Fruits of Instability .......................................................................................... 14 A. A Spike in Machete Gang Violence ............................................................................ 14 B. Mounting Pressure on the Mnangagwa Government ............................................... 15 C. A Large-scale Police Operation .................................................................................. 16 IV. Three Mines, Three Stories of Violence .......................................................................... -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

The Undersigned Authenticate That the the Midlands State University for Assessing Zimbabwean Local Housing: Challenges and Oppor

APPROVAL FORM The undersigned authenticate that they have supervised and recommended to the Midlands State University for acceptance the dissertation entitled: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Of Kwekwe City Council. Submitted by :Christiner Mjanga Reg. No. R134524H in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Sciences Honours Degree in Local Governance Studies. ..................................................... ...................................................... SUPERVISIOR DATE .................................................... ........................................................ CHAIRPERSON DATE i FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE RELEASE FORM Name of Student: Christiner Mjanga Registration Number: R134524H Dissertation title: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing- Challenges and Opportunities: Case of Kwekwe City Council. Degree to which Dissertation was presented: Bsc Honours in Local governance studies Year this degree granted: 2016 Permission is hereby granted to the Midlands State University library to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research only. The author reserves other publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author`s written permission. Signed ...................................................... -

Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Projects in Zimbabwe

Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Projects in Zimbabwe Amount Amount No Year Project Title Implementing Organisation District (US) (yen) 1 1989 Mbungu Primary School Development Project Mbungu Primary School Gokwe 16,807 2,067,261 2 1989 Sewing and Knitting Project Rutowa Young Women's Club Gutu 5,434 668,382 3 1990 Children's Agricultural Project Save the Children USA Nyangombe 8,659 1,177,624 Mbungo Uniform Clothing Tailoring Workshop 4 1990 Mbungo Women's Club Masvingo 14,767 2,008,312 Project Construction of Gardening Facilities in 5 1991 Cold Comfort Farm Trust Harare 42,103 5,431,287 Support of Small-Scale Farmers 6 1991 Pre-School Project Kwayedza Cooperative Gweru 33,226 4,286,154 Committee for the Rural Technical 7 1992 Rural Technical Training Project Murehwa 38,266 4,936,314 Training Project 8 1992 Mukotosi Schools Project Mukotosi Project Committee Chivi 20,912 2,697,648 9 1992 Bvute Dam Project Bvute Dam Project Committee Chivi 3,558 458,982 10 1992 Uranda Clinic Project Uranda Clinic Project Committee Chivi 1,309 168,861 11 1992 Utete Dam Project Utete Dam Project Committee Chivi 8,051 1,038,579 Drilling of Ten Boreholes for Water and 12 1993 Irrigation in the Inyathi and Tsholotsho Help Age Zimbabwe Tsholotsho 41,574 5,072,028 PromotionDistricts of ofSocialForestry Matabeleland andManagement Zimbabwe National Conservation 13 1993 Buhera 46,682 5,695,204 ofWoodlands inCommunalAreas ofZimbabwe Trust Expansion of St. Mary's Gavhunga Primary St. Mary's Gavhunga Primary 14 1994 Kadoma 29,916 3,171,096 School School Tsitshatshawa -

For Human Dignity

ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity REPORT ON: APRIL 2020 i DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT NATIONAL INQUIRY REPORT ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION ZIMBABWE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION For Human Dignity For Human Dignity TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. vii ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................................... ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................. xi PART A: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Establishment of the National Inquiry and its Terms of Reference ....................................................... 2 1.2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2: THE NATIONAL INQUIRY PROCESS ......................................................................................... -

Zimbabwe.Beef.20190321.Approved V2

Value Chain Analysis for Development (VCA4D) is a tool funded by the European Commission / DEVCO and is implemented in partnership with Agrinatura. Agrinatura (http://agrinatura-eu.eu) is the European AllianCe of Universities and Research Centers involved in agricultural researCh and CapaCity building for development. The information and knowledge produCed through the value Chain studies are intended to support the Delegations of the European Union and their partners in improving poliCy dialogue, investing in value Chains and better understanding the Changes linked to their aCtions VCA4D uses a systematiC methodologiCal framework for analysing value Chains in agriCulture, livestoCk, fishery, aquaCulture and agroforestry. More information inCluding reports and communication material Can be found at: https://europa.eu/CapaCity4dev/value-chain-analysis-for- development-vca4d- Team Composition Ben Bennett, Team Leader and eConomist (NRI) Muriel Figué, social expert (CIRAD) Mathieu Vigne, environmental expert (CIRAD) Charles Chakoma, national consultant (independent) Pamela KatiC, support to economist (NRI) The report was produCed through the finanCial support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of its authors and does not neCessarily refleCt the views of the European Union. The report has been realised within a projeCt finanCed by the European Union (VCA4D CTR 2016/375-804). Citation of this report: Bennett, B., Chakoma, C., Figué, M, Vigne, M., KatiC, P.; 2019. Beef Value Chain Analysis in Zimbabwe. Report for the -

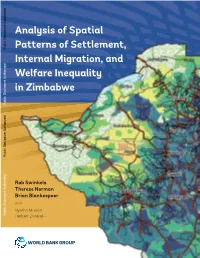

ANALYSIS of SPATIAL PATTERNS of SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, and WELFARE INEQUALITY in ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial

ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial Public Disclosure Authorized Patterns of Settlement, Internal Migration, and Welfare Inequality in Zimbabwe Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Rob Swinkels Therese Norman Brian Blankespoor WITH Nyasha Munditi Public Disclosure Authorized Herbert Zvirereh World Bank Group April 18, 2019 Based on ZIMSTAT data Zimbabwe District Map, 2012 Zimbabwe Altitude Map ii ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ix ABBREVIATIONS xv 1. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES 1 2. SPATIAL ELEMENTS OF SETTLEMENT: WHERE DID PEOPLE LIVE IN 2012? 9 3. RECENT POPULATION MOVEMENTS 27 4. REASONS BEHIND THE SPATIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERN AND POPULATION MOVEMENTS 39 5. CONSEQUENCES OF THE POPULATION’S SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION 53 6. POLICY DISCUSSION 71 AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH 81 REFERENCES 83 APPENDIX A. SUPPLEMENTAL MAPS AND CHARTS 87 APPENDIX B. RESULTS OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS 99 APPENDIX C. EXAMPLE OF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT INDEX 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a team led by Rob Swinkels, comprising Therese Norman and Brian Blankespoor. Important background work was conducted by Nyasha Munditi and Herbert Zvirereh. Wishy Chipiro provided valuable technical support. Overall guidance was provided by Andrew Dabalen, Ruth Hill, and Mukami Kariuki. Peer reviewers were Luc Christiaensen, Nagaraja Rao Harshadeep, Hans Hoogeveen, Kirsten Hommann, and Marko Kwaramba. Tawanda Chingozha commented on an earlier draft and shared the shapefiles of the Zimbabwe farmland use types. Yondela Silimela, Carli Bunding-Venter, Leslie Nii Odartey Mills, and Aiga Stokenberga provided inputs to the policy section.