Contesting Inequality in Access to Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Phd Thesis

Can We Learn Our Way to Sustainable Management? Adaptive Collaborative Management in Mafungautsi State Forest, Zimbabwe. Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Thesis committee Thesis supervisors Prof. dr. P. Richards Professor of Technology and Agrarian Development Wageningen University Prof. dr. K.E. Giller Professor of Plant Production Systems Wageningen University Thesis co-supervisor Dr. ir. C. J. M. Almekinders Assistant Professor, Technology and Agrarian Development Group Wageningen University Other members Prof. dr. ir. C. Leeuwis, Wageningen University Prof. dr. L.E. Visser, Wageningen University Dr. ir. K. F. Wiersum, Wageningen University Dr. B.B. Mukamuri, University of Zimbabwe This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Research School for Resource Studies for Development. Can We Learn Our Way to Sustainable Management? Adaptive Collaborative Management in Mafungautsi State Forest, Zimbabwe. Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M. J. Kropff in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 23 April 2010 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Can We Learn Our Way to Sustainable Management? Adaptive Collaborative Management in Mafungautsi State Forest, Zimbabwe. 231 pages Thesis Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2010) ISBN 978-90-8585-651-1 Dedication To my parents, my husband Simeon , my son Tafadzwa -

Zimbabwe-HIV-Estimates Report 2018

ZIMBABWE NATIONAL AND SUB-NATIONAL HIV ESTIMATES REPORT 2017 AIDS & TB PROGRAMME MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND CHILD CARE July 2018 Foreword The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) in collaboration with National AIDS Council (NAC) and support from partners, produced the Zimbabwe 2017 National, Provincial and District HIV and AIDS Estimates. The UNAIDS, Avenir Health and NAC continued to provide technical assistance and training in order to build national capacity to produce sub-national estimates in order to track the epidemic. The 2017 Estimates report gives estimates for the impact of the programme. It provide an update of the HIV and AIDS estimates and projections, which include HIV prevalence and incidence, programme coverages, AIDS-related deaths and orphans, pregnant women in need of PMTCT services in the country based on the Spectrum Model version 5.63. The 2017 Estimates report will assist the country to monitor progress towards the fast track targets by outlining programme coverage and possible gaps. This report will assist programme managers in accounting for efforts in the national response and policy makers in planning and resource mobilization. Brigadier General (Dr.) G. Gwinji Permanent Secretary for Health and Child Care Page | i Acknowledgements The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) would want to acknowledge effort from all individuals and organizations that contributed to the production of these estimates and projections. We are particularly grateful to the National AIDS Council (NAC) for funding the national and sub-national capacity building and report writing workshop. We are also grateful to the National HIV and AIDS Estimates Working Group for working tirelessly to produce this report. -

Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012

Zimbabwe Provincial Report Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012 Population Census Office P.O. Box CY342 Causeway Harare Tel: 04-793971-2 04-794756 E-mail: [email protected] Census Results for Midlands Province at a Glance Population Size Total 1 614 941 Males 776 787 Females 838 154 Annual Average Increase (Growth Rate) 2.2 Average Household Size 4.5 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................3 List of Tables.....................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................9 Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................10 Midlands Fact Sheet (Final Results) .................................................................................................13 Chapter 1: ........................................................................................................................................14 Population Size and Structure .......................................................................................................14 Chapter 2: ........................................................................................................................................24 Population Distribution -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

Pdf | 218.74 Kb

SOUTHERN AFRICA Flash Update No.11 – Tropical Cyclone Eloise As of 28 January 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • More than 270,000 people have been affected by Eloise across Southern Africa, including 267,289 in Mozambique, more than 1,000 in Zimbabwe and more than 1,000 in Eswatini. • The death toll from Eloise has risen to 21, including 11 in Mozambique, 3 in Zimbabwe, 4 in Eswatini, 2 in South Africa and 1 in Madagascar. • With flood waters present in multiple locations, the risk of water-borne diseases, including cholera, is high. • Tens of thousands of hectares of crops have been flooded due to the Eloise weather system, which could have consequences for the next harvest and food security in the period ahead. SITUATION OVERVIEW The Eloise weather system has left at least 21 people dead -11 in Mozambique, 3 in Zimbabwe, 4 in Eswatini, 2 in South Africa and 1 in Madagascar- and affected more than 270,000 people across Southern Africa, according to preliminary information which continues to be updated as new data becomes available. Although the damage wrought by Eloise to date has been less widespread than Tropical Cyclone Idai in 2019, homes, crops and infrastructure in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Eswatini and South Africa have been damaged or destroyed. In Mozambique, the number of people affected by Tropical Storm Eloise has risen to 267,289, as assessment teams have reached areas impacted by the storm and further information is becoming available. At least 20,167 people are sheltering in 32 temporary accommodation centres after being displaced by flooding, where urgent needs include clean water and sanitation to prevent disease outbreaks. -

State Power, Land-Use Planning, and Local Responses in Northwestern Zimbabwe, 1980S-1990S

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 14, Issue 4 | September 2014 State Power, Land-use Planning, and Local Responses in Northwestern Zimbabwe, 1980s-1990s PIUS S. NYAMBARA Abstract: The paper seeks to understand the rationale behind the introduction of the villagization program in post-independence rural Zimbabwe between the 1980s and the 1990s with a particular focus on the Gokwe South District. This is particularly interesting in that similar programs in the colonial era generated resentment and faced resistance among the rural population and were eventually abandoned. Given that the history of Africa is replete with examples of such programs that failed dismally, the most representative being the ujamaa experiment in post-colonial Tanzania, one wonders why a post-independence government would still have faith in such unpopular programs. The paper is based on fieldwork conducted between 1996 and 1997, and again in 2002-3 and more recently in 2011 in selected areas of Gokwe South District. The research made use of minutes of meetings of the Gokwe South Rural District Council, especially those of the Council’s Natural Resources Board and Resettlement Committee; national and local newspapers; interviews conducted with Village Development Committees (VIDCOs), chiefs, village heads, ward councilors, Council and Agritex officials, the district administration and ordinary villagers. Largely in response to the influx of immigrants into the district, among other factors, state officials in Gokwe constructed a land degradation narrative to justify the program. Research work revealed that the program was not adequately explained to Gokwe rural communities. However, the program was eventually overtaken by the land occupations of commercial farms that began around 1997 and dominated the Zimbambwean political landscape for much of the first decade of the twenty-first century. -

A History of Land Acquisition, Commercialisation O

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED SOCIAL RESEARCH SEMINAR PAPER TO BE PRESENTED IN THE RICHARD WARD BUILDING SEVENTH FLOOR, SEMINAR ROOM 7003 AT 4PM ON THE 26 MAY1997. TITLE: A History of Land Acquisition, Commercialisation of Agriculture and Socio- Economic Differentiation among Peasant Farmers in a Frontier Region: The Gokwe District of Northwestern Zimbabwe: c. 1945-1990s. BY p. NYAMBARA NO: 421 A HISTORY OF LAND ACQUISITION. COMMERCIALSATIQN OF AGRICULTURE AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DIFFERENTIATION AMONG PEASANT FARMERS IN A FRONTIER REGION: THE GOKWE DISTRICT OF NORTHWESTERN ZIMBABWE: c. 1945 - 1990S. A paper to be presented to the Institute for Advanced Social Research: University of the Wirwatersrand* Johannesburg on 26 th May* 1997. Pius S. Nyambara PhD Candidate, Northwestern University. A history of land acquisition, commercialisation of agriculture and socio-economic differentiation among peasant farmers in a frontier region: The Gokwe district of northwestern Zimbabwe, post 1945-1990s. Introduction Until the 1950s, Gokwe was once perceived as the wild, remote and economically 'backward' domain of the 'Shangwe1 people, but since the influx of immigrants from the south into this region, and the introduction of small-holder cotton production in the early 1960s, Gokwe has been represented as a miracle of agrarian transformation, a frontier of commoditization, and more broadly, as an exemplar of the transition to modernity. From the early 1960s to the mid-1980s Gokwe alone accounted for more than half the country's cotton production from the African areas, and about 15% of the national output. Today(1996), Gokwe contributes about 60 percent of the nation's cotton output and its high market price has spurred even the smallest farmer to master the art of growing the million dollar crop. -

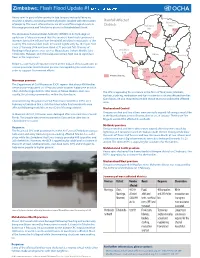

ZIM-Infographic-Flood-06 A4 07Feb2014 Zimbabwe Flash Flood - February 2014.Ai

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ © ¡ ¥ Heavy rains in parts of the country in late January and early February resulted in deaths and displacement of people, coupled with destruction Rainfall A!ected Mashonaland of property. The worst a!ected areas are Chivi and Masvingo districts in Districts Mashonaland Central Masvingo province and Tsholotsho district in Matabeleland North. West Shamva The Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) in its hydrological Makonde Binga update on 5 February warned that the country’s dam levels continue to Harare increase due to the in"ows from the rainfall activities in most parts of the Gokwe South country. The national dam levels increased signicantly by 10.29 per cent since 27 January 2014 and now stand at 71 per cent full. Chances of Mashonaland "ooding in "ood prone areas such as Muzarabani, Gokwe, Middle Sabi, Matabeleland East Tsholotsho, Malapati and Chikwalakwala remain high due to signicant North Midlands Manicaland "ows in the major rivers. Tsholotsho Gutu Bulawayo Below is a summary of reports received on the impact of incessant rains in Masvingo Chivi various provinces. Humanitarian partners are appealing for assistance in Matabeleland Masvingo order to support Government e!orts. Mangwe South A!ected districts Gwanda Mwenezi Chiredzi Masvingo province The Department of Civil Protection (DCP) reports that about 400 families needed to be evacuated on 3 February while another 4,000 were at risk in Chivi and Masvingo districts after levels at Tokwe-Mukorsi dam rose The CPC is appealing for assistance in the form of food, tents, blankets, rapidly, threatening communities within the dam basin. buckets, clothing, medication and fuel in order to assist the a!ected families. -

Faculty of Arts Department of Development Studies the Effects Of

FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES THE EFFECTS OF ARTISANAL SMALL-SCALE GOLD MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT: THE CASE OF WARD 25 (CHISINA 3) GOKWE SOUTH DISTRICT BY PETER MAPFUMO R131709V DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES HONOURS DEGREE. RESEARCH SUPERVISOR MR T CHIBANDA YEAR 2016 ~ i ~ Research supervision acknowledgement form MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Name of student Peter Mapfumo Reg Number R131709V Name of supervisor Mr T Chibanda Research Topic THE EFFECTS OF ARTISANAL SMALL-SCALE GOLD MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT THE CASE OF WARD 25 (CHISINA 3) GOKWE SOUTH DISTRICT I, the undersigned do/do not acknowledge that the above student has consulted me for supervision on his /her research project /dissertation until completion. I therefore do/do not advise the student to submit his/her work for assessment. Signed...................................................... Date............................................ ~ ii ~ Declaration I, Peter Mapfumo, declare that this thesis I have submitted is my own effort and also it has not been submitted anywhere for any degree purposes in any other university. I certify that the information in the thesis which is not my effort has been acknowledged. This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Arts in Development Studies Honors Degree at Midlands State University, Zvishavane campus. Signature Date ……………………… ……………………………….. ~ iii ~ Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my lovely wife Ethel Mwilawasa and son Kundai Nathanael Mapfumo, My late father Shadreck Dzingayi Mapfumo, my mother Rhoda Musemwa, My two sisters Juliet and Lucia Mapfumo and lastly my brothers Emmanuel Mapfumo, Simbarashe Mapfumo and Abraham Mapfumo for their financial support they gave to me during my study. -

Interaction Member Activity Report ZIMBABWE a Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of Interaction Member Agencies in Zimbabwe

InterAction Member Activity Report ZIMBABWE A Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of InterAction Member Agencies in Zimbabwe February 2008 Photo: Africare Produced by Jill Ruchala With the Humanitarian Policy and Practice Team, InterAction And with the support of a cooperative agreement with USAID/OFDA 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 210, Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 667-8227 Fax: (202) 667-8236 Website: www.interaction.org Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS...................................................................................................2 MAP OF ZIMBABWE......................................................................................................3 REPORT SUMMARY.......................................................................................................4 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND......................................................................................5 INTERACTION MEMBER AGENCIES CONTRIBUTING TO THIS REPORT…7 GLOSSARY OF ACROYNMS.........................................................................................8 LIST OF MEMBER ORGANIZATIONS BYSECTOR ACTIVITY………………..9 ADVENTIST DEVELOPMENT AND RELIEF AGENCY........................................10 AFRICARE.......................................................................................................................12 BAPTIST WORLD AID..................................................................................................14 BROTHER’S BROTHER FOUNDATION...................................................................15 -

Impact Assessment of the Gokwe Integrated Recovery Action Project Zimbabwe

Impact Assessment of the Gokwe Integrated Recovery Action Project Zimbabwe John C Burns • Omeno W Suji August 2007 Impact Assessment of Innovative Humanitarian projects in Sub-Saharan Africa The Feinstein International Center in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Africare Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Sekai Chikowero, Paul Chimedza, Stanley Masimbe, and James Machichiko, of Africare Zimbabwe for all their assistance and support during the mid term visits and final impact assessment. In particular we would like to thank Timm Musori for his participation and valuable contributions during the exercise. Our gratitude also goes to the rest of the Africare, Zimbabwe team for their hospitality and administrative support in Gokwe and Harare. To Dr Justice Nyamangara of the University of Zimbabwe for availing himself during the various technical presentations held in Harare, and for working on the baseline and indicator validation exercises. Many thanks also to the enumerators, Frank Magombezi, Paradza, Kunguvas, and Enock Muzenda for their valuable contribution during the final impact assessment. From the Feinstein International Center, thanks to Dr Peter Walker, Dr Andrew Catley, and Dr Dawit Abebe, for providing technical support. We would also like to thank Regine Webster, Mito Alfieri, and Kathy Cahill from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for all your support. 2 Contents Summary .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION