Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

Zimbabwe-HIV-Estimates Report 2018

ZIMBABWE NATIONAL AND SUB-NATIONAL HIV ESTIMATES REPORT 2017 AIDS & TB PROGRAMME MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND CHILD CARE July 2018 Foreword The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) in collaboration with National AIDS Council (NAC) and support from partners, produced the Zimbabwe 2017 National, Provincial and District HIV and AIDS Estimates. The UNAIDS, Avenir Health and NAC continued to provide technical assistance and training in order to build national capacity to produce sub-national estimates in order to track the epidemic. The 2017 Estimates report gives estimates for the impact of the programme. It provide an update of the HIV and AIDS estimates and projections, which include HIV prevalence and incidence, programme coverages, AIDS-related deaths and orphans, pregnant women in need of PMTCT services in the country based on the Spectrum Model version 5.63. The 2017 Estimates report will assist the country to monitor progress towards the fast track targets by outlining programme coverage and possible gaps. This report will assist programme managers in accounting for efforts in the national response and policy makers in planning and resource mobilization. Brigadier General (Dr.) G. Gwinji Permanent Secretary for Health and Child Care Page | i Acknowledgements The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) would want to acknowledge effort from all individuals and organizations that contributed to the production of these estimates and projections. We are particularly grateful to the National AIDS Council (NAC) for funding the national and sub-national capacity building and report writing workshop. We are also grateful to the National HIV and AIDS Estimates Working Group for working tirelessly to produce this report. -

Census Results in Brief

116 Appendix 1a: Census Questionnaire 117 118 119 120 Appendix 1b: Census Questionnaire Code List Question 6-8 and 10 Census District Country code MANICALAND 1 Sanyati 407 Shurugwi 726 Rural Districts Urban Areas MASVINGO 8 Buhera 101 Chinhoyi 421 Rural Districts Chimanimani 102 Kadoma 422 Bikita 801 Chipinge 103 Chegutu 423 Chiredzi 802 Makoni 104 Kariba 424 Chivi 803 Mutare Rural 105 Norton 425 Gutu 804 Mutasa 106 Karoi 426 Masvingo Rural 805 Nyanga 107 MATABELELAND NORTH 5 Mwenezi 806 Urban Areas Rural Districts Zaka 807 Mutare 121 Binga 501 Urban Areas Rusape 122 Bubi 502 Masvingo Urban 821 Chipinge 123 Hwange 503 Chiredzi Town 822 MASHONALAND CENTRAL 2 Lupane 504 Rural Districts Nkayi 505 HARARE 9 Bindura 201 Tsholotsho 506 Harare Rural 901 Centenary 202 Umguza 507 Harare Urban 921 Guruve 203 Urban Areas Chitungwiza 922 Mazowe 204 Hwange 521 Epworth 923 Mount Darwin 205 Victoria Falls 522 BULAWAYO 0 Rushinga 206 MATABELELAND SOUTH 6 Bulawayo Urban 21 Shamva 207 Rural Districts AFRICAN COUNTRIES Mbire 208 Beitbridge Rural 601 Zimbabwe 0 Urban Areas Bulilima 602 Botswana 941 Bindura 221 Mangwe 603 Malawi 942 Mvurwi 222 Gwanda Rural 604 Mozambique 943 MASHONALAND EAST 3 Insiza 605 South Africa 944 Rural Districts Matobo 606 Zambia 945 Chikomba 301 Umzingwane 607 Other African Countries 949 Goromonzi 302 Urban Areas OUTSIDE AFRICA Hwedza 303 Gwanda 621 United Kingdom 951 Marondera 304 Beitbridge Urban 622 Other European Countries 952 Mudzi 305 Plumtree 623 American Countries 953 Murehwa 306 MIDLANDS 7 Asian Countries 954 Mutoko 307 Rural Districts Other Countries 959 701 Seke 308 Chirumhanzu Uzumba-Maramba-Pfungwe 309 Gokwe North 702 Urban Areas Gokwe South 703 Marondera 321 Gweru Rural 704 Chivhu Town Board 322 Kwekwe Rural 705 Ruwa Local Board 323 Mberengwa 706 MASHONALAND WEST 4 Shurugwi 707 Rural Districts Zvishavane 708 Chegutu 401 Urban Areas Hurungwe 402 Gweru 721 Mhondoro-Ngezi 403 Kwekwe 722 Kariba 404 Redcliff 723 Makonde 405 Zvishavane 724 Gokwe Centre 725 . -

Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012

Zimbabwe Provincial Report Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012 Population Census Office P.O. Box CY342 Causeway Harare Tel: 04-793971-2 04-794756 E-mail: [email protected] Census Results for Midlands Province at a Glance Population Size Total 1 614 941 Males 776 787 Females 838 154 Annual Average Increase (Growth Rate) 2.2 Average Household Size 4.5 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................3 List of Tables.....................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................9 Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................10 Midlands Fact Sheet (Final Results) .................................................................................................13 Chapter 1: ........................................................................................................................................14 Population Size and Structure .......................................................................................................14 Chapter 2: ........................................................................................................................................24 Population Distribution -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

Pdf | 218.74 Kb

SOUTHERN AFRICA Flash Update No.11 – Tropical Cyclone Eloise As of 28 January 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • More than 270,000 people have been affected by Eloise across Southern Africa, including 267,289 in Mozambique, more than 1,000 in Zimbabwe and more than 1,000 in Eswatini. • The death toll from Eloise has risen to 21, including 11 in Mozambique, 3 in Zimbabwe, 4 in Eswatini, 2 in South Africa and 1 in Madagascar. • With flood waters present in multiple locations, the risk of water-borne diseases, including cholera, is high. • Tens of thousands of hectares of crops have been flooded due to the Eloise weather system, which could have consequences for the next harvest and food security in the period ahead. SITUATION OVERVIEW The Eloise weather system has left at least 21 people dead -11 in Mozambique, 3 in Zimbabwe, 4 in Eswatini, 2 in South Africa and 1 in Madagascar- and affected more than 270,000 people across Southern Africa, according to preliminary information which continues to be updated as new data becomes available. Although the damage wrought by Eloise to date has been less widespread than Tropical Cyclone Idai in 2019, homes, crops and infrastructure in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Eswatini and South Africa have been damaged or destroyed. In Mozambique, the number of people affected by Tropical Storm Eloise has risen to 267,289, as assessment teams have reached areas impacted by the storm and further information is becoming available. At least 20,167 people are sheltering in 32 temporary accommodation centres after being displaced by flooding, where urgent needs include clean water and sanitation to prevent disease outbreaks. -

ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee

SIRDC VAC ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Financed by: Implementation partners: The ZimVAC acknowledges the personnel, time and material The Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines was made possible by contributions of all implementing partners that made this work contributions from the following ZimVAC members who supported possible the process in data collection, analysis and report writing: Office of the President and Cabinet Food and Nutrition Council Ministry of Local Government, Rural and Urban Development Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation and Irrigation Development For enquiries, please contact the ZimVAC Chair: Ministry of Labour and Social Services Food and Nutrition Council Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency SIRDC Complex Ministry of Health and Child Welfare 1574 Alpes Road, Hatcliffe, Harare, Zimbabwe Ministry of Education, Sports, Arts and Culture Save the Children Tel: +263 (0)4 883405, +263 (0)4 860320-9, Concern Worldwide Email: [email protected] Oxfam Web: www.fnc.org.zw Action Contre la Faim Food and Agriculture Organisation World Food Programme United States Agency for International Development FEWS NET The Baseline work was coordinated by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) with Save the Children providing technical leadership on behalf of ZimVAC. Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee August 2011 Page | 1 Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Acknowledgements Funding for the Zimbabwe Livelihoods Baseline Project was provided by the Department for International Development (DFID) and the European Commission (EC). The work was implemented under the auspices of the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee chaired by George Kembo. Daison Ngirazi and Jerome Bernard from Save the Children Zimbabwe provided management and technical leadership. -

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 25 March 2011 ZIMBABWE 25 MARCH 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN ZIMBABWE FROM 22 FEBRUARY 2011 TO 24 MARCH 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON ZIMBABWE PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 22 FEBRUARY 2011 AND 24 MARCH 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Public holidays ..................................................................................................... 1.06 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 Remittances .......................................................................................................... 2.06 Sanctions .............................................................................................................. 2.08 3. HISTORY (19TH CENTURY TO 2008)............................................................................. 3.01 Matabeleland massacres 1983 - 87 ..................................................................... 3.03 Political events: late 1980s - 2007...................................................................... 3.06 Events in 2008 - 2010 ........................................................................................... 3.23 -

State Power, Land-Use Planning, and Local Responses in Northwestern Zimbabwe, 1980S-1990S

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 14, Issue 4 | September 2014 State Power, Land-use Planning, and Local Responses in Northwestern Zimbabwe, 1980s-1990s PIUS S. NYAMBARA Abstract: The paper seeks to understand the rationale behind the introduction of the villagization program in post-independence rural Zimbabwe between the 1980s and the 1990s with a particular focus on the Gokwe South District. This is particularly interesting in that similar programs in the colonial era generated resentment and faced resistance among the rural population and were eventually abandoned. Given that the history of Africa is replete with examples of such programs that failed dismally, the most representative being the ujamaa experiment in post-colonial Tanzania, one wonders why a post-independence government would still have faith in such unpopular programs. The paper is based on fieldwork conducted between 1996 and 1997, and again in 2002-3 and more recently in 2011 in selected areas of Gokwe South District. The research made use of minutes of meetings of the Gokwe South Rural District Council, especially those of the Council’s Natural Resources Board and Resettlement Committee; national and local newspapers; interviews conducted with Village Development Committees (VIDCOs), chiefs, village heads, ward councilors, Council and Agritex officials, the district administration and ordinary villagers. Largely in response to the influx of immigrants into the district, among other factors, state officials in Gokwe constructed a land degradation narrative to justify the program. Research work revealed that the program was not adequately explained to Gokwe rural communities. However, the program was eventually overtaken by the land occupations of commercial farms that began around 1997 and dominated the Zimbambwean political landscape for much of the first decade of the twenty-first century. -

Final Book2.Indd

Sub-National Food Security Information System Livelihoods Profiles Zimbabwe Livelihood Profiles Table of Contents Table of Contents Acknowledgements Acronyms and Abbreviations Introduction Objective of the Report Methodology Background to Vulnerability and Risk Analysis Livelihoods Based Vulnerability Assessment Approach Livelihoods Zoning Wealth Break Down Analysis of Livelihoods Strategies Baseline + Hazard + Response = Outcome Field work Brief Background on Zimbabwe The Seven Food Economy Zones, Baseline Profiles Introduction Livelihood Zones Sub National FSIS general seasonal Calendar Rural Sources of Food and Cash Income Main Findings and Implications Poor Resources Kariba Valley, Kariangwe Jambezi Communal FEZ: Siabuwa Nebiri Low Cotton Producing Communal FEZ Kanyati High Potential FEZ Agro-fisheries ( Gache-Gache )FEZs Greater Northern Gokwe High Cotton Producing Communal FEZ Lusulu Lupane Southern Gokwe Platuea Mixed Agriculture FEZ Lusulu Lupane Southern Gokwe Lowlands Mixed Agiculture FEZ Greater Mudzi Communal FEZ Zimbabwe Livelihood Profiles Zimbabwe Livelihood Profiles Acknowledgements Acronyms and Abbreviations AIDS Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome CFSAM Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission CSO Central Statistics Office DFID Department For International Development Save the Children (UK) Zimbabwe, Catholic Relief Services and Concern World Wide (CWW) would EMOP Emergency Operations like to express their gratitude to the districts of Binga, Kariba, Mudzi, UMP, Nyanga North, Gokwe FANR Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources Directorate (SADC) North and South for their support towards the assessments used for the livelihoods profiles. Spe- FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation cific thanks is offered to the departments for Agriculture Research and Extension (AGRITEX) and District Aids Action Committees (DAAC) who provided some of the secondary data required for FEZ Food Economy Zone the Vulnerability Assessment and Analysis (VAA). -

A History of Land Acquisition, Commercialisation O

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED SOCIAL RESEARCH SEMINAR PAPER TO BE PRESENTED IN THE RICHARD WARD BUILDING SEVENTH FLOOR, SEMINAR ROOM 7003 AT 4PM ON THE 26 MAY1997. TITLE: A History of Land Acquisition, Commercialisation of Agriculture and Socio- Economic Differentiation among Peasant Farmers in a Frontier Region: The Gokwe District of Northwestern Zimbabwe: c. 1945-1990s. BY p. NYAMBARA NO: 421 A HISTORY OF LAND ACQUISITION. COMMERCIALSATIQN OF AGRICULTURE AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DIFFERENTIATION AMONG PEASANT FARMERS IN A FRONTIER REGION: THE GOKWE DISTRICT OF NORTHWESTERN ZIMBABWE: c. 1945 - 1990S. A paper to be presented to the Institute for Advanced Social Research: University of the Wirwatersrand* Johannesburg on 26 th May* 1997. Pius S. Nyambara PhD Candidate, Northwestern University. A history of land acquisition, commercialisation of agriculture and socio-economic differentiation among peasant farmers in a frontier region: The Gokwe district of northwestern Zimbabwe, post 1945-1990s. Introduction Until the 1950s, Gokwe was once perceived as the wild, remote and economically 'backward' domain of the 'Shangwe1 people, but since the influx of immigrants from the south into this region, and the introduction of small-holder cotton production in the early 1960s, Gokwe has been represented as a miracle of agrarian transformation, a frontier of commoditization, and more broadly, as an exemplar of the transition to modernity. From the early 1960s to the mid-1980s Gokwe alone accounted for more than half the country's cotton production from the African areas, and about 15% of the national output. Today(1996), Gokwe contributes about 60 percent of the nation's cotton output and its high market price has spurred even the smallest farmer to master the art of growing the million dollar crop. -

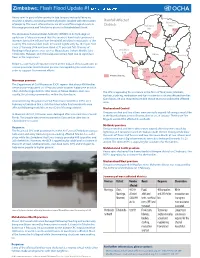

ZIM-Infographic-Flood-06 A4 07Feb2014 Zimbabwe Flash Flood - February 2014.Ai

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ © ¡ ¥ Heavy rains in parts of the country in late January and early February resulted in deaths and displacement of people, coupled with destruction Rainfall A!ected Mashonaland of property. The worst a!ected areas are Chivi and Masvingo districts in Districts Mashonaland Central Masvingo province and Tsholotsho district in Matabeleland North. West Shamva The Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) in its hydrological Makonde Binga update on 5 February warned that the country’s dam levels continue to Harare increase due to the in"ows from the rainfall activities in most parts of the Gokwe South country. The national dam levels increased signicantly by 10.29 per cent since 27 January 2014 and now stand at 71 per cent full. Chances of Mashonaland "ooding in "ood prone areas such as Muzarabani, Gokwe, Middle Sabi, Matabeleland East Tsholotsho, Malapati and Chikwalakwala remain high due to signicant North Midlands Manicaland "ows in the major rivers. Tsholotsho Gutu Bulawayo Below is a summary of reports received on the impact of incessant rains in Masvingo Chivi various provinces. Humanitarian partners are appealing for assistance in Matabeleland Masvingo order to support Government e!orts. Mangwe South A!ected districts Gwanda Mwenezi Chiredzi Masvingo province The Department of Civil Protection (DCP) reports that about 400 families needed to be evacuated on 3 February while another 4,000 were at risk in Chivi and Masvingo districts after levels at Tokwe-Mukorsi dam rose The CPC is appealing for assistance in the form of food, tents, blankets, rapidly, threatening communities within the dam basin. buckets, clothing, medication and fuel in order to assist the a!ected families.