Oswald De Andrade's "Cannibalist Manifesto" 37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Betazos/Pontedeume 13/05/2016

Betazos/Pontedeume 13/05/2016 NOTAS SOBRE OS ANDRADE Mª LUZ RÍOS RODRÍGUEZ I. AS ORIXES. S. XII-XIII -1ª mención en 1160: Bermudo Fortúnez, miles de Andrade. -Membros da baixa nobreza, vasalos dos Traba (Froilaz, Ovéquiz, Gómez) que son o maior poder nobiliar, auténticos “comes Galliciae”, que dominan as terras e condados de Pruzos, Bezoucos (Bisaquis), Trasancos, Trastamara, Sarria, Montenegro. A relación vasalática dos Andrade se continuará a ata a extinción da familia Traba a fins do s. XIII (último representante Rodrigo Gómez). -Pequeno dominio con bens e vasalos en san Martiño de Andrade (berce da liñaxe), Pontedeume, Cabanas, Monfero, Vilarmaior, Montenegro. Relacións de mutuo beneficio ( pactos) cos mosteiros de Cabeiro, Monfero e Bergondo. Despois encomendeiros, defendendo en teoría aos mosteiros, pero usurpando tamén moitas das súas rendas e vasalos ( por ex: no s. XIII, Fernán Pérez de Andrade I (1230-ca1260/1270), encomendeiro de Monfero). -Van enriquecéndose grazas a concesión de beneficios por parte dos seus señores (Traba) e sobre todo de préstamos/ pactos e encomendas dos mosteiros, así como grazas a matrimonios vantaxosos: bens mais seguros, patrimoniais, si hai herdeiros. -No s. XIII a monarquía reasegura o seu poder fronte a nobreza cas fundacións/ cartas poboas das vilas de Ferrol, Pontedeume, Vilalba , As Pontes. II. O CAMBIO SOCIOPOLÍTICO. s. XIV A.- 1ª ½ XIV: os Andrade á sombra dos Castro. -- No reino, últimos monarcas da dinastía afonsina ou borgoñona: Afonso XI e Pedro I. -- Na Galicia, os mais grandes señores son agora os Castro, que son tamén os novos señores dos Andrade (Pedro Fernández de Castro, o da guerra, (+Algeciras, 1342) señor de Monforte de Lemos e Sarria, e seu fillo, Fernán Ruiz de Castro, toda a lealdade de España,( +Bayonne, 1377), III conde de Lemos, Trastamara e Sarria. -

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico Manuscripts New Spain Finding Aid Prepared by David M

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts New Spain Finding aid prepared by David M. Szewczyk. Last updated on January 24, 2011. PACSCL 2010.12.20 New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Summary Information Repository PACSCL Title New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Call number New Spain Date [inclusive] 1519-1855 Extent 5.8 linear feet Language Spanish Cite as: [title and date of item], [Call-number], New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts, 1519-1855, Rosenbach Museum and Library. Biography/History Dr. Rosenbach and the Rosenbach Museum and Library During the first half of this century, Dr. Abraham S. W. Rosenbach reigned supreme as our nations greatest bookseller. -

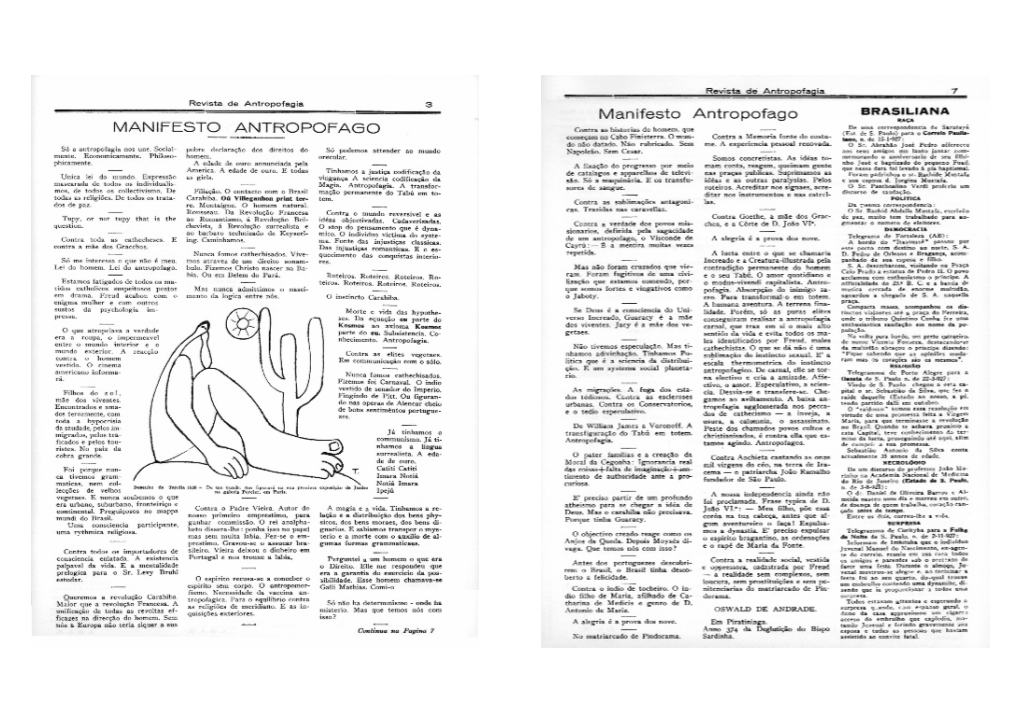

Oswald De Andrade's "Cannibalist Manifesto" Author(S): Leslie Bary Source: Latin American Literary Review, Vol

Oswald de Andrade's "Cannibalist Manifesto" Author(s): Leslie Bary Source: Latin American Literary Review, Vol. 19, No. 38 (Jul. - Dec., 1991), pp. 35-37 Published by: Latin American Literary Review Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20119600 Accessed: 06/08/2009 13:23 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=lalr. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Latin American Literary Review is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Latin American Literary Review. http://www.jstor.org OSWALD DE ANDRADE'S "CANNIBALISTMANIFESTO" LESUEBARY Introduction The Brazilian modernist poet Oswald de Andrade's "Manifesto Antrop?fago" (MA) originally appeared in the first number of Revista de Antropofagia, the S?o Paulo cultural review directed by Alc?ntara Machado and Raul Bopp, in May, 1928. -

The North Way

PORTADAS en INGLES.qxp:30X21 26/08/09 12:51 Página 6 The North Way The Pilgrims’ Ways to Santiago in Galicia NORTE EN INGLES 2009•.qxd:Maquetación 1 25/08/09 16:19 Página 2 NORTE EN INGLES 2009•.qxd:Maquetación 1 25/08/09 16:20 Página 3 The North Way The origins of the pilgrimage way to Santiago which runs along the northern coasts of Galicia and Asturias date back to the period immediately following the discovery of the tomb of the Apostle Saint James the Greater around 820. The routes from the old Kingdom of Asturias were the first to take the pilgrims to Santiago. The coastal route was as busy as the other, older pilgrims’ ways long before the Spanish monarchs proclaimed the French Way to be the ideal route, and provided a link for the Christian kingdoms in the North of the Iberian Peninsula. This endorsement of the French Way did not, however, bring about the decline of the Asturian and Galician pilgrimage routes, as the stretch of the route from León to Oviedo enjoyed even greater popularity from the late 11th century onwards. The Northern Route is not a local coastal road for the sole use of the Asturians living along the Alfonso II the Chaste. shoreline. This medieval route gave rise to an Liber Testamenctorum (s. XII). internationally renowned current, directing Oviedo Cathedral archives pilgrims towards the sanctuaries of Oviedo and Santiago de Compostela, perhaps not as well- travelled as the the French Way, but certainly bustling with activity until the 18th century. -

San Martiño De Mondoñedo / 1235 San Martiño De Mondoñedo

SAN MARTIÑO DE MONDOÑEDO / 1235 SAN MARTIÑO DE MONDOÑEDO La iglesia de San Martiño de Mondoñedo se encuentra en medio de un pintoresco paisaje de la brumosa y lluviosa Galicia cantábrica. Está situada en la comarca de la Mariña Lucense, a tan solo 5 km de Foz, municipio al que pertenece la parroquia de San Martín. La mejor ruta para llegar es a través de la A-8 o autovía del Cantábrico, ya sea procedentes de Baamonde y Vilalba, o de Riba- deo y Luarca, donde tomaremos el desvío señalizado de Foz (N-642) y, antes de entrar en la villa, nos desviaremos por una carretera local (LU-152) que nos conducirá hasta el ábside de la iglesia. Se trata de uno de los conjuntos más singulares del arte medieval gallego, en el que se mezcla de manera indisociable la realidad con la leyenda. Aunque la iglesia se la conoce popularmente co- mo “la catedral más antigua de España”, este resulta un término exagerado, ya que el edificio actual no es anterior a finales del siglo XI, si bien reaprovecha muchos elementos de la fábrica del siglo X. Como es bien sabido, sus orígenes están ligados a la traslación, por parte de Alfonso III, en el año 866, de la antigua sede de Dumio (Portugal) a este lugar, conocido como Mondoñedo de Foz (Mendunieto, Mondumeto o Monte Dumetum). Allí se instaló su primer obispo, Sabarico I (866-877), hui- do de Portugal, que dedicó a San Martín de Dumio la nueva iglesia y la dotó supuestamente con una reliquia traída desde la antigua sede (FLÓREZ, H., 1974, XVII, pp. -

Oswald De Andrade Obras Completas-10

OSWALD DE ANDRADE OBRAS COMPLETAS-10 TELEFONEMA RETRATO DE UM HOMEM E DE UMA ÉPOCA. TELEFONEMA, é uma antologia da produção jornalística de Oswald de Andrade a partir de 1909, quando re- digiu a coluna teatral do Diário Po- pular, até sua última crônica para o Correio da Manhã, divulgada no dia seguinte ao de sua morte. A seleção e estabelecimento dos textos são de Vera Chalmers, jovem universitária e pesquisadora de altos méritos que integra a equipe de estu- diosos formada pelo Professor Antô- nio Cândido de Melo e Souza. Dela também a valiosa e esclarecedora in- trodução crítica, onde analisa, com inteligência e agudeza, o discurso jor- nalístico de Oswald de Andrade. As notas de rodapé, situando fatos e pes- soas, são igualmente de sua autoria. Esses textos foram desentranhados das secções fixas mantidas pelo escri- tor em vários órgãos da imprensa: Teatros e Salões, Feira das Quintas, Banho de Sol, De Literatura, Feira das Sextas, Três Linhas e Quatro Verdades e Telefonema, aparecidas intermitentemente em jornais como Diário Popular, Jornal do Comércio (edição de São Paulo), Meio-Dia, Diário de São Paulo, Folha de São Paulo e Correio da Manhã. A reunião dessas crônicas e artigos acaba por formar um "retrato" espiri- tual do polígrafo paulista, um gráfi- co febril das suas mutações intelec- tuais, os conflitos de sua índole in- conformada, as inquietações que o assoberbaram ao longo dos anos. Ne- las estão as suas paixões, iras, ind os- sincrasias, alguns momentos polêmi- cos da maior virulência, ou de sátira Oswald de Andrade Obras Completas X Telefonema 2.a edição Introdução e estabelecimento do texto de VERA CHALMERS civilização brasileira Copyright © by Espólio de OSWALD DE ANDRADE Desenho de capa: DOUNÊ Diagramação: ciVBR Ás Direitos desta edição reservados à EDITORA CIVILIZAÇÃO BRASILEIRA S.A. -

Parques Naturales De Galicia Fragas Do Eume

Parques Naturales de Galicia Fragas do Eume Experiencias en plena naturaleza ES Todos los verdes para explorar EL ULTIMO BOSQUE ATLÁNTICO Ven a conocer uno de los bosques atlánticos de ribera mejor que conservan un espectacular manto vegetal. Robles y conservados de Europa. En sus 9.000 hectáreas de extensión castaños son muy abundantes, acompañados de otras viven menos de 500 personas, lo que da una idea del estado variedades como abedules, alisos, fresnos, tejos, avellanos, virgen de estos exuberantes bosques que siguen el curso árboles frutales silvestres, laureles, acebos y madroños. En del río Eume. El Parque tiene la forma de un triángulo cuyos las riberas húmedas y sombrías se conserva una amplia vértices y fronteras son las localidades de As Pontes de García colección de más de 20 especies de helechos y 200 especies Rodríguez, Pontedeume y Monfero. de líquenes. Un simple paseo por este territorio se convierte El río Eume, con 100 kilometros de longitud, labra un en una auténtica exploración de este bosque mágico. profundo cañón de abruptas laderas con grandes desniveles ACCESOS: El acceso más frecuente se lleva a cabo desde la localidad de Pontedeume, donde podremos coger la carretera DP-6902, paralela al río Eume, hasta llegar al Centro de interpretación. La entrada al Parque con vehículos de motor está restringida, por lo que conviene llamar antes para consultar dichas restricciones. MÁS INFORMACIÓN SOBRE EL PARQUE Y LAS EXPERIENCIAS QUE TE PROPONEMOS EN: Centro de Interpretación de las Fragas do Eume Lugar de Andarúbel. Carretera de Ombre a Caaveiro, km 5. 15600 Pontedeume T. -

Media Inter Media

Brazilian Arts The Migration of Poetry to Videos and Installations Solange Ribeiro de Oliveira Opening with statements made by representative poets of the last two decades, this essay discusses aspects of contemporary Brazilian poetic output. As demon- strated by the poets in question, Brazilian poetry still lives in the shadow of the great masters of the recent past, such as Fernando Pessoa, Manuel Bandeira, Carl- os Drummond de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade, Murilo Mendes, João Cabral de Mello Neto, and the concrete poets. Yet, there is no such thing as a general poet- ics, reducible to a set of parameters or to a common theoretical framework. This plural character of Brazilian poetry, however, does not exclude certain dominant traits, such as an emphasis on craftsmanship, rewriting, hermeticism, irony, and a problematic subject. Nonetheless, a few poets seem to refuse mere verbal play and insist on honoring the pact of communication with the reader. Discussing the qualities of ‘the poetic’, this essay culminates in a discussion of the special rela- tionship that poetry has with other artistic manifestations, such as videos and in- stallations. Por que a poesia tem de se confinar Às paredes de dentro da vulva do poema? Waly Salomão, Lábia 1. Introduction Lovers of Brazilian literature may well wonder how Brazilian poetry is doing nowadays, and what, indeed, has been going on since the 1960s. It would perhaps be a good idea to hand this question on to the poets themselves, to try and hear from them whatever can be said about their art, which has become more impossible than ever to de- fine. -

Catanduva.Sp.Gov.Br |

www.catanduva.sp.gov.br | www.imprensaoficialmunicipal.com.br/catanduva Segunda-feira, 16 de outubro de 2017 Ano XII | Edição nº 922 Página 1 de 67 SUMÁRIO IMPRENSA OFICIAL PODER EXECUTIVO DE CATANDUVA 2 Lei nº 3833, de 27 de dezembro de 2002, regulamentada pelo Decreto Municipal nº 4653, de 25 de outubro de 2005. Atos Oficiais 2 Publicação centralizada e coordenada pela Assessoria de Portarias 2 Comunicação Social da Prefeitura de Catanduva - SP. Licitações e Contratos 3 Contato: [email protected] Aditivos / Aditamentos / Supressões 3 Telefone: 3531-9122 Contratos - Convocação 3 As edições do Diário Oficial Eletrônico de Catanduva Aviso de Licitação 3 poderão ser consultadas através da internet, no endereço Outros Atos 5 eletrônico: www.catanduva.sp.gov.br Para pesquisa por qualquer termo e utilização de filtros, Errata 5 acesse www.imprensaoficialmunicipal.com.br/catanduva As consultas e pesquisas são de acesso gratuito e Secretaria Municipal de Saúde 5 independente de qualquer cadastro. PODER LEGISLATIVO DE CATANDUVA 59 ENTIDADES Atos Legislativos 59 Prefeitura Municipal de Catanduva Portarias 59 CNPJ 45.122.603/0001-02 Outros atos 59 Pç Conde Francisco Matarazzo, Centro Licitações e Contratos 60 Telefone: 0800-772-9152 Aviso de Licitação 60 Câmara Municipal de Catanduva CNPJ 51.840.544/0001-00 Pç Conde Francisco Matarazzo, Centro Instituto Municipal de Ensino Superior - IMES - FAFICA 60 Telefone: (17) 3524-9600 Concursos Públicos / Processos Seletivos 60 Instituto de Previdência do Município de Catanduva - Edital 60 IPMC CNPJ 45.118.189/0001-50 Rua Sergipe, nº 796 - Centro Telefone: (17) 3523-7583 Instituto Municipal de Ensino Superior - IMES - FAFICA CNPJ 51.843.795/0001-30 Avenida Daniel Dalto (Rodovia Washington Luis - SP 310 - Km 382) Caixa Postal 86 Telefone: (17) 3521-2200 Superintendência de Água e Esgoto de Catanduva CNPJ 10.559.279/0001-00 Rua São Paulo, nº. -

Ireland and Latin America: a Cultural History

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Ireland and Latin America: a cultural history Murray, Edmundo Abstract: According to Declan Kiberd, “postcolonial writing does not begin only when the occupier withdraws: rather it is initiated at that very moment when a native writer formulates a text committed to cultural resistance.” The Irish in Latin America – a continent emerging from indigenous cultures, colonisation, and migrations – may be regarded as colonised in Ireland and as colonisers in their new home. They are a counterexample to the standard pattern of identities in the major English-speaking destinations of the Irish Diaspora. Using literary sources, the press, correspondence, music, sports, and other cultural representations, in this thesis I search the attitudes and shared values signifying identities among the immigrants and their families. Their fragmentary and wide-ranging cultures provide a rich context to study the protean process of adaptation to, or rejection of, the new countries. Evolving from oppressed to oppressors, the Irish in Latin America swiftly became ingleses. Subsequently, in order to join the local middle classes they became vaqueros, llaneros, huasos, and gauchos so they could show signs of their effective integration to the native culture, as seen by the Latin American elites. Eventually, some Irish groups separated from the English mainstream culture and shaped their own community negotiating among Irishness, Englishness, and local identities in Brazil, Uruguay, Peru, Cuba, and other places in the region. These identities were not only unmoored in the emigrants’ minds but also manoeuvred by the political needs of community and religious leaders. -

Pioneer Tree Responses to Variation of Soil Attributes in a Tropical Semi-Deciduous Forest in Brazil

Journal of Sustainable Forestry ISSN: 1054-9811 (Print) 1540-756X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wjsf20 Pioneer tree responses to variation of soil attributes in a tropical semi-deciduous forest in Brazil Maria Teresa V. N. Abdo, Sergio V. Valeri, Antonio S. Ferraudo, Antonio Lucio M. Martins & Leandro R. Spatti To cite this article: Maria Teresa V. N. Abdo, Sergio V. Valeri, Antonio S. Ferraudo, Antonio Lucio M. Martins & Leandro R. Spatti (2017) Pioneer tree responses to variation of soil attributes in a tropical semi-deciduous forest in Brazil, Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 36:2, 134-147, DOI: 10.1080/10549811.2016.1264880 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2016.1264880 Accepted author version posted online: 02 Dec 2016. Published online: 06 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 54 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wjsf20 JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY 2017, VOL. 36, NO. 2, 134–147 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2016.1264880 Pioneer tree responses to variation of soil attributes in a tropical semi-deciduous forest in Brazil Maria Teresa V. N. Abdoa, Sergio V. Valerib, Antonio S. Ferraudoc, Antonio Lucio M. Martinsa, and Leandro R. Spattia aPolo Centro Norte-APTA (São Paulo Agency for Agribusiness), Pindorama, SP, Brazil; bUNESP, FCAV, Department of Vegetal Production, Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil; cUNESP, FCAV, Department of Exact Sciences, Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The occurrence of pioneer tree species inside tropical forests is Acacia polyphylla; Aloysia usually associated with canopy openness due to disturbances. -

Colonization and Epidemic Diseases in the Upper Rio Negro Region, Brazilian Amazon (Eighteenth-Nineteenth Centuries)* 1 Boletín De Antropología, Vol

Boletín de Antropología ISSN: 0120-2510 Universidad de Antioquia Buchillet, Dominique Colonization and Epidemic Diseases in the Upper Rio Negro Region, Brazilian Amazon (Eighteenth-Nineteenth Centuries)* 1 Boletín de Antropología, vol. 33, no. 55, 2018, January-June, pp. 102-122 Universidad de Antioquia DOI: 10.17533/udea.boan.v33n55a06 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=55755367005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Colonization and Epidemic Diseases in the Upper Rio Negro Region, Brazilian Amazon (Eighteenth-Nineteenth Centuries)1 Dominique Buchillet Doctorate in Anthropology (medical anthropology) Independent researcher (former researcher at the French Institute of Research for Development-IRD) Email-address: [email protected] Buchillet, Dominique (2018). “Colonization and Epidemic Diseases in the Upper Rio Negro Region, Brazilian Amazon (Eighteenth-Nineteenth Cen- turies)”. En: Boletín de Antropología. Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, vol. 33, N.º 55, pp. 102-122. DOI: 10.17533/udea.boan.v33n55a06 Texto recibido: 24/04/2017; aprobación final: 04/10/2017 Abstract. This paper examines demographic and health impacts of the colonization of the upper Rio Negro region during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Smallpox, measles, and epidemic fevers plagued native populations, contributing to the depopulation of the region and depleting the Indian workforce crucial to the economic survival of the Portuguese colony and the Brazilian empire. It examines how colonists and scientists explained the biological vulnerability to smallpox and measles, two major killers of Indians during these periods, and also discusses the nature of the diseases that plagued Indian populations.