Forging Asian American Identity Through the Basement Workshop By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Are Laotian Americans? April 2015

Who Are Laotian Americans? April 2015 Laotian American Asian American U.S. The Laotian American average average average National population1 population grew faster U.S. residents, 2013 246,000 19.2 million 316 million than the U.S. average Population growth, 2010–2013 6.3 percent 10.9 percent 2.4 percent between 2000 and Population growth, 2000–2013 25 percent 62 percent 12 percent 2013, and Laotian Top states of residence2 Americans are much California 79,331 6,161,975 38,332,521 more likely to be first- Texas 16,419 1,282,731 26,448,193 Minnesota 14,831 279,984 5,420,380 generation immigrants Washington 11,225 709,237 6,971,406 than the U.S. average. Georgia 8,229 420,533 9,992,167 Total population in these states 130,035 8,854,460 87,164,667 Educational attainment3 Less than a high school degree 32 percent 14 percent 13.4 percent High school degree or equivalent 30 percent 16 percent 28 percent Bachelor’s degree or higher 13 percent 49 percent 29.6 percent Income and poverty4 Median 12-month household income $58,000 $71,709 $53,046 Share in poverty overall 13.8 percent 12.8 percent 15.7 percent Share of children in poverty 39 percent 13.6 percent 22.2 percent Share of seniors in poverty 6 percent 13.5 percent 9.3 percent 1 Center for American Progress | Who Are Laotian Americans? Laotian American Asian American U.S. average average average Civic participation5 Turnout among registered voters in 2012 40 percent 79 percent 87 percent Vote in 2012 (percent Obama/Romney) 71/29 68/31 51/47 Party identification (percent Democrat/ *** 33/14/53 24/32/38 Republican/neither) Language diversity6 Speak language other than English at home 83 percent 77/70 percent* 21 percent Limited English proficiency, or LEP 41 percent 35/32 percent* 8.5 percent Share of linguistically isolated households 18 percent 17 percent 5 percent Most common language: Laotian, spoken by 150,600 people Immigration and nativity7 Share who are foreign born 59 percent 66 percent 15 percent Share who are U.S. -

Beyond the Streets

BEYOND THE STREETS TOMIE ARAI PORTRAITS OF NEW YORK CHINATOWN ANNIE LING A FLOATING POPULATION DECEMBER 13, 2013%–%APRIL 13, 2014 BeyondTheStreets_booklet_10.indd 1 12/4/13 2:25 PM CHINATOWN: BEYOND THE STREETS As with any neighborhood designation, the that were in danger of being forgotten in a term ‘Chinatown’ signals a set of associations rapidly changing neighborhood. that can be misleading and one-dimensional. These associations are often derived from Manhattan’s Chinatown has continued to the streets. But storefronts cannot tell the full change since the 1980s due in no small part to story of a neighborhood, and in fact, they can the rise of Chinese enclaves in Queens and sometimes betray a hidden truth. For example, Brooklyn, increased immigration from Fujian Mulberry Street is generally understood to be province, real estate development within the center of Little Italy (and the Italian restau- Chinatown and in bordering neighborhoods, rants on the street level would seem to prove and a host of other factors. Today’s Chinatown that) but Chinese residents occupy many of is diverse and dynamic, and MOCA remains the tenement apartments above. However, committed to telling the untold stories of this nobody really thinks Mulberry Street between community before they are lost and forgotten. Canal and Broome Street should, for this fact, be called ‘Chinatown’. Through projects by artists Annie Ling and Tomie Arai, we attempt to look beyond the In civic life, names of streets, neighborhoods streets into the interior life of Chinatown, and institutions matter because they describe its domestic spaces and collective memory. -

Southeast Asian Americans at a Glance

SOUTHEAST ASIAN AMERICANS AT A GLANCE Statistics on Southeast Asians adapted from the American Community Survey Last Updated: 10/06/2011 Table of Contents POPULATION, IMMIGRATION, & NATURALIZATION Southeast Asian Americans Reporting One or More Ethnic/Racial Designation ......................................................................... 5 Percentages of People in Age Groups by Population ................................................................................................................... 6 By Age Category and Sex ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Refugee Arrivals to the U.S. from Southeast Asia ........................................................................................................................ 7 People from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, Naturalized as U.S. Citizens ................................................................................... 8 Percentages of Foreign-Born People, Naturalized as U.S. Citizen & Not a Citizen ...................................................................... 9 People Reporting Southeast Asian Heritage, Born in the United States...................................................................................... 9 EDUCATION Educational Attainment of People Aged 25 and Over ............................................................................................................... 11 Language Characteristics by Percentage of Population 5 Years and -

Asian Americans: the "Reticent" Minority and Their Paradoxes

William & Mary Law Review Volume 36 (1994-1995) Issue 1 Article 2 October 1994 Asian Americans: The "Reticent" Minority and Their Paradoxes Pat K. Chew Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Repository Citation Pat K. Chew, Asian Americans: The "Reticent" Minority and Their Paradoxes, 36 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1 (1994), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol36/iss1/2 Copyright c 1994 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr William and Mary Law Review VOLUME 36 No. 1, 1994 ASIAN AMERICANS: THE "RETICENT" MINORITY AND THEIR PARADOXES PAT K. CHEW* I. DISTORTIONS AND PARADOXES ..................... 8 A. Paradox:Asian Americans Are Not DiscriminatedAgainst, but They Are ........... 8 1. History of Express Discrimination ......... 9 2. Ongoing Express Discrimination .......... 18 * Professor of Law, University of Pittsburgh School of Law. J.D. 1982, M.Ed. 1974, University of Texas; A.B. 1972 Stanford University. This Article is dedicated to my children, Lauren and Luke. I also thank the fol- lowing individuals for reviewing a draft of the Article and for their many valuable insights: Robert Kelley, Anita Allen, Jody Armour, Ruth Colker, Richard Delgado, Nitya Iyer, Jules Lobel, Mari Matsuda, Michael Olivas, Syed Shariq, Johnna Torsonne, Rhonda Wasserman, and Alfred Yen. The views and conclusions voiced in this Article, however, may not reflect the views of these individuals. My research assistants Nancy Burkoff, Jennifer Su Kim, and George Magera were very helpful. I also am grateful for the financial assistance and support provided for this project by former Dean Mark Nordenberg and the Dean's Scholarship Award, and the secre- tarial assistance provided by the Law School's Word Processing Department. -

Pacific Citizen Sansei Farmer Hopeful Youth Lnill Return to the Family

i- Newsstand: 25¢ postpaid (U.S., Can.) I (Japan Air) $1.50 $2.30 #29911 Vol. 136, o.8 0030-8579 MAY 2-15,2003 N ISSN: National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) 34th Annual Manzanar Pilgrimage CC/PSW/NCWNP TRI-DISTRICT CONFERENCE Recognizes Jerome, Poston Camps By MARTHA NAKAGAWA Sansei Farmer Hopeful Youth lNill Assistant Editor Return to the Family Business At the 34th annual Manzanar By CA ROLINE AOYA GI Pilgrimage, the Jerome and Executive Editor Poston War Relocation Authority camps were recognized, and a rep VISALIA, Cali f.-Tad Kozuki resentative from Nikkei for Civil is part of a rare group these days in Rights and Redress' (NCRR) 9/11 the Central California Va lley. committee shared some of the A third-generation Japanese activities they've been involved in American farmer, Kozuki, 63, and to ensure that what happened to his two brothers have been run Japanese Americans during World ning the fa mily farm in Parlier, a War II does not happen again to city just south of Fresno, for more Muslim and Arab Americans. than fo ur decades now but so far Representing Jerome was Joe their kids, eight in total, have no Yamakido, the only known draft interest in continuing the family resister from the Jerome camp in business. Arkansas. Ya makido refused to It's a trend Kozuki sees through- PHOTO: CAROLINE AOYAGI serve in the U.S. military until his . out the valley here. As one of the Irene and Tad Kozuki at the recent tri-district conference in Visalia. -

Asian North Americans' Leisure: a Critical Examination of the Theoretical Frameworks Used in Research and Suggestions for Future Study

Leisure Sciences An Interdisciplinary Journal ISSN: 0149-0400 (Print) 1521-0588 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ulsc20 Asian North Americans' Leisure: A Critical Examination of the Theoretical Frameworks Used in Research and Suggestions for Future Study Kangjae Jerry Lee & Monika Stodolska To cite this article: Kangjae Jerry Lee & Monika Stodolska (2017) Asian North Americans' Leisure: A Critical Examination of the Theoretical Frameworks Used in Research and Suggestions for Future Study, Leisure Sciences, 39:6, 524-542, DOI: 10.1080/01490400.2016.1215944 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1215944 Published online: 30 Aug 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 121 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ulsc20 Download by: [Dr KangJae Jerry Lee] Date: 15 October 2017, At: 15:46 LEISURE SCIENCES ,VOL.,NO.,– http://dx.doi.org/./.. Asian North Americans’ Leisure: A Critical Examination of the Theoretical Frameworks Used in Research and Suggestions for Future Study Kangjae Jerry Leea and Monika Stodolskab aDepartment of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism, University of Missouri at Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA; bDepartment of Recreation, Sport and Tourism, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The aim of this study was to critically examine the theoretical frame- Received November works employed in the existing research on Asian North Americans’ Accepted July leisure and to offer insights into additional theories that might beused KEYWORDS in future research on the topic. -

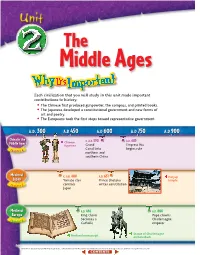

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

A Community of Contrasts: Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians And

2015 A COMMUNITY OF CONTRASTS Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the West ARIZONA HAWAI‘I LAS VEGAS OREGON SEATTLE CONTENTS Welcome 1 OREGON 46 Introduction 2 Demographics 47 Executive Summary Economic Contributions3 49 Civic Engagement 50 WEST REGION Immigration 5 51 Demographics 6 Language 52 ARIZONA 10 Education 53 Demographics 11 Income 54 Economic Contributions 13 Employment 55 Civic Engagement 14 Housing 56 Immigration 15 Health 57 Language 16 SEATTLE METRO AREA 58 Education 17 Demographics 59 Income 18 Economic Contributions 61 Employment 19 Civic Engagement 62 Housing 20 Immigration 63 Health 21 Language 64 HAWAI‘I 22 Education 65 Demographics 23 Income 66 Economic Contributions 25 Employment 67 Civic Engagement 26 Housing 68 Immigration 27 Health 69 Language 28 Policy Recommendations 70 Education 29 Glossary 73 Income 30 Appendix A: Population, Population Growth 74 Employment 31 Appendix B: Selected Population Characteristics 80 Housing 32 Technical Notes 85 Health 33 LAS VEGAS 34 METRO AREA Demographics 35 Economic Contributions 37 Civic Engagement 38 Immigration 39 Asian Americans Advancing Justice Language 40 Asian Americans Advancing Justice is a national affiliation of five leading organizations advocating for the civil and Education 41 human rights of Asian Americans and other underserved Income 42 communities to promote a fair and equitable society for all. Employment 43 Housing 44 Advancing Justice | AAJC (Washington, DC) Health 45 Advancing Justice | Asian Law Caucus (San Francisco) Advancing Justice | Atlanta Advancing Justice | Chicago Advancing Justice | Los Angeles All photos in this report were taken by M. Jamie Watson unless otherwise noted. Data design and layout were provided by GRAPHEK. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY 56th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2015. All the World’s Futures. @ Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz, site-specific show. Alcatraz Island National Historic Landmark, 2014–15. Ahmed, Sara. 1998. Differences That Matter: Feminist Theory and Postmodernism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Anthes, Bill. 2006. Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960. Durham: Duke University Press. Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. Araeen, Rasheed. 1987. Third Text. London: Kala Press. Armstrong, Carol, and Catherine de Zegher, eds. 2006. Women Artists at the Millennium. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Asian/American/Modern Art: Shifting Currents, 1900–1970. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, de Young Museum, 2008–9. Exhibition brochure. Asian American Women Artists Association. http://aawaa.net/. Barboza, David. 2008. Chinese Art Continues to Soar at Sotheby’s. New York Times, April 10. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/10/arts/design/10auct.html. Bee, Susan, and Mira Schor, eds. 2000. M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism. Durham: Duke University Press. Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge. Bigelow, Catherine. 2010. Stars Shine at the Shanghai Opening-Night Gala. SFgate.com, February 12. http://blog.sfgate.com/missbigelow/2010/02/ 12/stars-shine-at-the-shanghai-opening-night-gala/. © The Author(s) 2018 221 L. Fantone, Local Invisibility, Postcolonial Feminisms, Critical Studies in Gender, Sexuality, and Culture, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50670-2 222 Bibliography Bloom, Lisa. 2006. Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity. -

Lexicon Dreams and Chinese Rock and Roll: Thoughts on Culture, Language, and Translation As Strategies of Resistance and Reconstruction

University of Miami Law Review Volume 53 Number 4 Article 27 7-1-1999 Lexicon Dreams and Chinese Rock and Roll: Thoughts on Culture, Language, and Translation as Strategies of Resistance and Reconstruction Sharon K. Hom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Sharon K. Hom, Lexicon Dreams and Chinese Rock and Roll: Thoughts on Culture, Language, and Translation as Strategies of Resistance and Reconstruction, 53 U. Miami L. Rev. 1003 (1999) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol53/iss4/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lexicon Dreams and Chinese Rock and Roll: Thoughts on Culture, Language, and Translation as Strategies of Resistance and Reconstruction SHARON K. HoM* Good morning. I want to first thank the wonderful conference organizers, especially Frank Valdes and Lisa Iglesias, for their hard work. This is my first LatCrit conference and it has been a very special experience. Because of LatCrit's broad theoretical concerns and inclu- sive political project to expand coalition strategies,1 I trust my remarks today on culture and language across a transnational fame will not sound too "foreign." I'd like to take advantage of these supportive, critical and challenging conversations, to think out loud about a couple of ideas that might not fit neatly within traditional legal discourses. -

Sholette.CV.WINTER.2010 Copy

Gregory Sholette [email protected] 646-319-6387 Assistant Professor Art Department Queens College: CUNY 65-30 Kissena Boulevard Flushing, NY 11367 EDUCATION The Whitney Museum Independent Studies Program, Helena Rubinstein Fellow in Critical Studies, NYC. 1995. University of California San Diego, Visual Art Department, 1992-1995, Master of Fine Arts, CA, 1995. The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science & Art, 1977-1979, Bachelor of Fine Arts, NYC, 1979. Bucks County Community College, 1974-1976, Associate Degree (Fine Arts), Newtown, PA, 1976. TEACHING Queens College, Assistant Professor, Department of Art, 2/06/08 to the present. Harvard University, Visiting Professor, Dept. of Visual & Environmental Studies, Visiting Professor, Spring 2011. Geneva University of Art & Design, Seminar Leader, CCC: Critical,Curatorial,Cybermedia Research Program (ongoing Spring). Tromsø, Art Academy, Norway, Seminar Leader and final studio critiques, 5/26/09. Central European University, Budapest, Theory Seminars, Tranzit Free School/Art Theory/Practice. HU, 10/10-11/08. The Cooper Union, NYC, Art Department, Adjunct Professor, multiple semesters: 1997, 99, 07, 08. Malmö Art Academy, Sweden, Seminars, Post-Graduate Critical Studies Program, 4/8-10/07. Parsons School of Design, Adjunct Professor, Dept. of Art & Design Studies, Fall, 2006. New York University, Adjunct Professor, Art & Public Policy;Visual Studies Programs, Spring 2005, 06, 07. Eddin Foundation, Cairo, Egypt, Workshop Seminar for the Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), 12/05. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Assistant Professor, Arts Administration & Visual Critical Studies.9/99–5/04. Colgate University, Hamilton, NY, “The Distinguished Batza Family Chair in Art and Art History,” Spring, 2004. -

TRACING the INDEX: 4 DISCUSSIONS, 4 VENUES March 2Nd – March 31St, 2008

INDEX OF THE DISAPPEARED PRESENTS TRACING THE INDEX: 4 DISCUSSIONS, 4 VENUES March 2nd – March 31st, 2008 The series: Tracing the Index is a four-part series of roundtable discussions organized by Index of the Disappeared (Chitra Ganesh + Mariam Ghani), hosted and co-sponsored by the Bronx Museum of the Arts, NYU’s Kevorkian Institute, the New School’s Vera List Center for Art + Politics, and Art in General. The series brings together artists, activists and scholars to discuss ideas and areas of inquiry central to their work and to our collaborative project. All roundtables in the series will be recorded and made freely available online. We will also transcribe, edit and eventually publish the discussions, both online and in a forthcoming Index print publication. The roundtables: Collaboration + Feminism, Bronx Museum of the Arts, 3/2 at 3 pm Impossible Archives, Kevorkian Center, NYU, 3/3 at 5:30 pm Collaboration + Context, Art in General, 3/26 at 6:30 pm Agency and Surveillance, New School, 3/31 at 6:30 pm The format: This series is primarily focused on fostering the exchange of ideas, rather than introducing new work to new audiences (though we hope you may be intrigued enough by these artists’ ideas to seek out their work). For this reason, all the programs will have a roundtable rather than a presentation panel format. Participants will briefly introduce themselves and/or their work, and then participate in a moderated discussion focused on topical questions. The second hour of each roundtable will be open to questions from the audience.