Beyond the Streets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sholette.CV.WINTER.2010 Copy

Gregory Sholette [email protected] 646-319-6387 Assistant Professor Art Department Queens College: CUNY 65-30 Kissena Boulevard Flushing, NY 11367 EDUCATION The Whitney Museum Independent Studies Program, Helena Rubinstein Fellow in Critical Studies, NYC. 1995. University of California San Diego, Visual Art Department, 1992-1995, Master of Fine Arts, CA, 1995. The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science & Art, 1977-1979, Bachelor of Fine Arts, NYC, 1979. Bucks County Community College, 1974-1976, Associate Degree (Fine Arts), Newtown, PA, 1976. TEACHING Queens College, Assistant Professor, Department of Art, 2/06/08 to the present. Harvard University, Visiting Professor, Dept. of Visual & Environmental Studies, Visiting Professor, Spring 2011. Geneva University of Art & Design, Seminar Leader, CCC: Critical,Curatorial,Cybermedia Research Program (ongoing Spring). Tromsø, Art Academy, Norway, Seminar Leader and final studio critiques, 5/26/09. Central European University, Budapest, Theory Seminars, Tranzit Free School/Art Theory/Practice. HU, 10/10-11/08. The Cooper Union, NYC, Art Department, Adjunct Professor, multiple semesters: 1997, 99, 07, 08. Malmö Art Academy, Sweden, Seminars, Post-Graduate Critical Studies Program, 4/8-10/07. Parsons School of Design, Adjunct Professor, Dept. of Art & Design Studies, Fall, 2006. New York University, Adjunct Professor, Art & Public Policy;Visual Studies Programs, Spring 2005, 06, 07. Eddin Foundation, Cairo, Egypt, Workshop Seminar for the Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), 12/05. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Assistant Professor, Arts Administration & Visual Critical Studies.9/99–5/04. Colgate University, Hamilton, NY, “The Distinguished Batza Family Chair in Art and Art History,” Spring, 2004. -

TRACING the INDEX: 4 DISCUSSIONS, 4 VENUES March 2Nd – March 31St, 2008

INDEX OF THE DISAPPEARED PRESENTS TRACING THE INDEX: 4 DISCUSSIONS, 4 VENUES March 2nd – March 31st, 2008 The series: Tracing the Index is a four-part series of roundtable discussions organized by Index of the Disappeared (Chitra Ganesh + Mariam Ghani), hosted and co-sponsored by the Bronx Museum of the Arts, NYU’s Kevorkian Institute, the New School’s Vera List Center for Art + Politics, and Art in General. The series brings together artists, activists and scholars to discuss ideas and areas of inquiry central to their work and to our collaborative project. All roundtables in the series will be recorded and made freely available online. We will also transcribe, edit and eventually publish the discussions, both online and in a forthcoming Index print publication. The roundtables: Collaboration + Feminism, Bronx Museum of the Arts, 3/2 at 3 pm Impossible Archives, Kevorkian Center, NYU, 3/3 at 5:30 pm Collaboration + Context, Art in General, 3/26 at 6:30 pm Agency and Surveillance, New School, 3/31 at 6:30 pm The format: This series is primarily focused on fostering the exchange of ideas, rather than introducing new work to new audiences (though we hope you may be intrigued enough by these artists’ ideas to seek out their work). For this reason, all the programs will have a roundtable rather than a presentation panel format. Participants will briefly introduce themselves and/or their work, and then participate in a moderated discussion focused on topical questions. The second hour of each roundtable will be open to questions from the audience. -

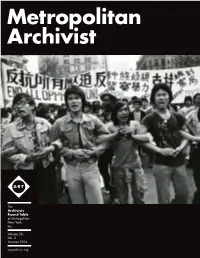

The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. Volume 20, No. 2 Summer 2014

Metropolitan Archivist The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. Volume 20, No. 2 Summer 2014 nycarchivists.org Welcome! The following individuals have joined the Archivists Round Table We extend a special thank you to the following of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) from January 2014 to June 2014 members for their support as A.R.T. Sustaining Members: Gaetano F. Bello, Corrinne Collett, New Members Anthony Cucchiara, Constance de Ropp, Barbara John Brokaw Haws, Chris Lacinak, Sharon Lehner, Liz Kent Cynthia Brenwall León, Alice Merchant, Sanford Santacroce Maureen Callahan The Michael Carter Thank you to our Sponsorship Members: Archivists Celestina Cuadrado Ann Butler, Frank Caputo, Linda Edgerly, Chris Round Table of Metropolitan Jacqueline DeQuinzio Genao, Celia Hartmann, David Kay, Stephen New York, Elizabeth Fox-Corbett Perkins, Marilyn H. Pettit, Alix Ross, Craig Savino Inc. Tess Hartman-Cullen Carmen Lopez The mission of Metropolitan Archivist is to Sam Markham serve members of the Archivists Round Table of Volume 20, Brian Meacham Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) by: No. 2 Chloe Pfendler - Informing them of A.R.T. activities through Summer 2014 David Rose reports of monthly meetings and committee Angela Salisbury activities nycarchivists.org Natalia Sucre - Relating important announcements about Marissa Vassari individual members and member repositories - Reporting important news related to the New York Board of Directors New Student Members metropolitan area archival profession Pamela Cruz Carlos Acevado - Providing a forum to discuss archival issues President Elizabeth Berg Ryan Anthony Thomas Cleary Metropolitan Archivist (ISSN 1546-3125) is Donaldson Vice President Rina Eisenberg issued semi-annually to the members of A.R.T. -

Forging Asian American Identity Through the Basement Workshop By

Title Page Out of the Basement: Forging Asian American Identity through the Basement Workshop by Christina Noelle Ong Bachelor of the Arts in Political Science, University of California, Irvine, 2014 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Christina Noelle Ong It was defended on June 12, 2019 and approved by Dr. Suzanne Staggenborg, Professor, Department of Sociology Dr. Melanie Hughes, Professor, Department of Sociology Thesis Advisor: Dr. Joshua Bloom, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology ii Copyright © by Christina Noelle Ong 2019 iii Abstract Out of the Basement: Forging Asian American Identity through the Basement Workshop Christina Noelle Ong, MA University of Pittsburgh, 2019 This thesis uncovers how and to what extent the establishment and early organizing activities of Basement Workshop (1969-1972) influenced the construction of an Asian American identity in juxtaposition to members’ identities that originated in their ethnic heritage. Through my research, I disrupt binary conceptions of the Asian diaspora as either a menace to white America or as bodies of docile complicity to white supremacy through an in-depth case study of Basement Workshop, the East Coast’s first pan-Asian political and arts organization. Using interviews with former members of Basement Workshop and historical discourse analysis of the organization’s magazine publications, arts anthology, and organizational correspondences, I demonstrate how Basement Workshop developed an Asian American identity which encompassed ideas about anti-imperialism, anti-racism, and anti-sexism. -

Un-Glitz: Art Activism and Global Cities” Location: A/P/A Institute at NYU, 8 Washington Mews, New York, NY Time: 6Pm-8Pm

“Un-glitz: Art Activism and Global Cities” Location: A/P/A Institute at NYU, 8 Washington Mews, New York, NY Time: 6pm-8pm Presented by Steinhardt Global Integration Fund in collaboration with A/P/A Institute at NYU and the NYU Global Asia/Pacific Art Exchange this discussion will focus on ongoing artistic production on land use in global cities in a comparative conversation between artist practitioners working on gentrification issues in New York’s lower east side, the rural reconstruction movement in rural villages on the outskirts of Shanghai, and West Kowloon Cultural District and other development in Hong Kong. The Lower East Side and Chinatown from the 1970s to the present has seen a drastic shift from art studios, grassroots arts organizations and multiple migrant communities to becoming the home of The New Museum, a new grouping of commercial art gallery spaces, and high-end condo developments. Both Chinatown and the Lower East Side has been caught in this change, and artist spaces and artists have moved and relocated to spaces such as Brooklyn. Artist Tomie Arai’s “Portraits of New Chinatown” is a project inspired from interviews with local residents to learn about the lived experience of those within the changing community of Chinatown. Artist Bing Lee, who will participate in the program via Skype, was the founder of Epoxy Group and co-founder of Godzilla: Asian American Artist Network and lived and worked in Chinatown along with artists including Ming Fay, Kwok Frog King, Ik-Joong Kang, Arlan Huang, HN Han among others of the 1970s and 1980s Lower East Side and Chinatown arts scene. -

Enrique Chagoya • Punk Aesthetics and the Xerox Machine • German

March – April 2012 Volume 1, Number 6 Enrique Chagoya • Punk Aesthetics and the Xerox Machine • German Romantic Prints • IPCNY / Autumn 2011 Annesas Appel • Printmaking in Southern California • Alex Katz • Renaissance Prints • News • Directory TANDEM PRESS www.tandempress.wisc.edu Doric a recent print by Sean Scully Sean Scully Doric, 2011 Etching and aquatint, ed. 40 30 1/4 by 40 inches http://www.tandempress.wisc.edu [email protected] 201 South Dickinson Street Madison, Wisconsin, 53703 Phone: 608.263.3437 Fax:608.265.2356 image© Sean Scully March – April 2012 In This Issue Volume 1, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Anarchy Managing Editor Sarah Kirk Hanley 3 Julie Bernatz Visual Culture of the Nacirema: Enrique Chagoya’s Printed Codices Associate Editor Annkathrin Murray David Ensminger 17 The Allure of the Instant: Postscripts Journal Design from the Fading Age of Xerography Julie Bernatz Catherine Bindman 25 Looking Back at Looking Back: Annual Subscriptions Collecting German Romantic Prints Art in Print is available in both digital and print form. Our annual membership Exhibition Reviews 30 categories are listed below. For complete descriptions, please visit our website at M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp Proof: The Rise of Printmaking in http://artinprint.org/index.php/magazine/ Southern California subscribe. You can also print or copy the Membership Subscription Form (page 63 Susan Tallman in this Journal) and send it with payment IPCNY New Prints 2011 / Autumn in US dollars to the address shown -

T He a Ndy W a Rh Ol F Ounda Tio N Fo R Th E V Is Ual a Rts

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts 20-Year Report 1987–2007 Grants and Exhibitions The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts 20-Year Report 1987–2007 Grants and Exhibitions List of Grants 04 Program Grants 04 Warhol Initiative 65 Arts Writing Initiative 67 9/11 Emergency Fund For Lower Manhattan Visual Arts Organizations 67 Katrina Relief Emergency Fund 68 List of Exhibitions 70 Solo Exhibitions 70 Group Exhibitions 77 ©2007 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. 65 Bleecker Street, 7th Floor New York, NY 10012 telephone 212-387-7555 fax 212-387-7560 www.warholfoundation.org Works appearing in this publication may not be reproduced without authorization from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. ISBN 0-9765263-1-X List of Grants 1989 Program Grants 1989 Cardinal Hayes High School Exit Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology, The New York Studio School Bronx, NY New York, NY List Visual Arts Center New York, NY American Federation of Arts Art materials and equipment New York City Tableaux: Tompkins Square Cambridge, MA Scholarship support New York, NY $25,000 Krzysztof Wodiczko exhibition and James Coleman residency $12,000 1989 Whitney Biennial of Film and Video tour catalogue $20,000 $15,000 Cathedral High School $25,000 P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center New York, NY MTA Arts for Transit Long Island City, NY American Museum of the Moving Image Art and computer equipment The Film Society of Lincoln Center New York, NY Publications program Astoria, NY $36,500 New York, NY Permanent Pat Steir installation for Eastern $25,000 Video equipment 1990 New Directors/New Films Parkway/Brooklyn Museum Transit Station $25,000 Checkerboard Foundation, Inc. -

Asian American Matters

ASIAN AMERICAN MATTERS A NEW YORK ANTHOLOGY Tomie Arai | Artist Tomie Arai, Tomorrow’s World Is Yours to Build DITOR EONG | E (2017). Photo by Cheung Ching Ming RUSSELL C. L ASIAN AMERICAN AND ASIAN RESEarCH INSTITUTE THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AsiAn AMericAn MAtters Why Do Asian American Matters, Matter? Russell C. Leong, Editor 11 1 TAKING ON A Post-9/11 WORLD WITH ASIAN American STUDIES 19 Asian American Studies, the War on Terror, and the Changing University: A Call to Respond Moustafa Bayoumi 21 Who are Asian Americans? Prema Kurien 25 Seize the Moment: A Time for Asian American Activism Rajini Srikanth 28 ‘Why Do You Study Islam?’: Religion, Blackness, and the Limits of Asian American Studies Sylvia Chan-Malik 31 Caught in a Racial Paradox: Middle Eastern American Identity and Islamophobia Erik Love 34 Why Asian Americans Need a New Politics of Dissent Eric Tang 38 Coalition-Building in the Inter-Disciplines and Beyond Mariam Durrani 40 Beneath the Surface: Academic and Practical Realities Raymond Fong 42 2 Fifty YEARS OF Pasts & FUTURES 47 Demographics, Geographies, Institutions: The Changing Intellectual Landscape of Asian American Studies Shirley Hune 49 Betty Lee Sung: Teaching Asian American Studies at CUNY An Interview Antony Wong 53 Forty-Five Years of Asian American Studies at Yale University Don T. Nakanishi 57 Why Asian Pacific Americans Need Liberatory Education More Than Ever Phil Tajitsu Nash 67 Asian American Matters 5 Asian Americans at The City University of New York: The Current Outlook Joyce O. Moy 77 Steps