Lexicon Dreams and Chinese Rock and Roll: Thoughts on Culture, Language, and Translation As Strategies of Resistance and Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Red Sonic Trajectories - Popular Music and Youth in China de Kloet, J. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): de Kloet, J. (2001). Red Sonic Trajectories - Popular Music and Youth in China. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:08 Oct 2021 L4Trif iÏLK m BEGINNINGS 0 ne warm summer night in 1991, I was sitting in my apartment on the 11th floor of a gray, rather depressive building on the outskirts of Amsterdam, when a documentary on Chinese rock music came on the TV. I was struck by the provocative poses of Cui Jian, who blindfolded himself with a red scarf - stunned by the images of the crowds attending his performance, images that were juxtaposed with accounts of the student protests of June 1989; and puzzled, as I, a rather distant observer, always imagined China to be a totalitarian regime with little room for dissident voices. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Above Ground or Under Ground: The Emergence and Transformation of "Sixth Generation" Film-Makers in Mainland China by Wu Liu B.A., Renmin University, 1990 M.A., Beijing Film Academy, 1996 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Pacific and Asian Studies © Wu Liu, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40466-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40466-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development

THE SAXOPHONE IN CHINA: HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE AND DEVELOPMENT Jason Pockrus Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Eric M. Nestler, Major Professor Catherine Ragland, Committee Member John C. Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pockrus, Jason. The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 222 pp., 12 figures, 1 appendix, bibliography, 419 titles. The purpose of this document is to chronicle and describe the historical developments of saxophone performance in mainland China. Arguing against other published research, this document presents proof of the uninterrupted, large-scale use of the saxophone from its first introduction into Shanghai’s nineteenth century amateur musical societies, continuously through to present day. In order to better describe the performance scene for saxophonists in China, each chapter presents historical and political context. Also described in this document is the changing importance of the saxophone in China’s musical development and musical culture since its introduction in the nineteenth century. The nature of the saxophone as a symbol of modernity, western ideologies, political duality, progress, and freedom and the effects of those realities in the lives of musicians and audiences in China are briefly discussed in each chapter. These topics are included to contribute to a better, more thorough understanding of the performance history of saxophonists, both native and foreign, in China. -

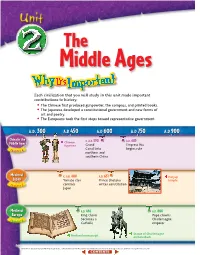

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

Maintaining the Rage

China Supplement 41 appearance. It should be noted, of the neighbourhood committees higher echelons of the party would however, that the mass-line in polic will aid the police in maintaining require a degree of political move ing was strengthened, not as a result social order in the community. What ment the current leadership is clear of the triumphant march forward of the mass line in policing is less com ly not willing to countenance. In socialism but, on the contrary, of a petent at doing—and in the present place of reform, the current leader crisis in policing brought on by political climate this is possibly a ship offers to resurrect Lei Feng and economic reform. fatal flaw— is policing middle and Mao. For all too many Chinese, how high ranking party and government ever, Lei Feng and Mao are not a Will such resurrections, then, lead officials who are involved in corrupt means by which China can go ‘back China ‘back to the future’, back to a practices. to the future' but are themselves popular/populist form of socialism? back in the past. For all too many Probably n ot, althou gh these The ultimate question, then, is not Chinese, it's now time to move for measures will continue to function whether we go ‘back to the future’ ward. adequately, to be maintained and but whether the mass line in polic even extended. Campaigns will ing is capable of doing anything lower—albeit temporarily—certain other than policing the masses. To MICHAEL DUTTON1 teaches in political science at Melbourne University. -

Following the Footprints of Music in Tiananmen Square Protests Wang Meng

From the Highest Court to the Furthest Wasteland: Following the Footprints of Music in Tiananmen Square Protests Wang Meng Music has always been an important component of social movements. As the one and only protest of its scale and influence in China, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests was a lively music venue. Protesters sang revolutionary songs and played rock music on cassette tapes players in the tent city. At night, the square turned into a concert and dance floor. (Gordon & Hinton, 1995) Cui Jian and Hou Dejian, the two most popular musicians at the time, performed for the protesters on the square. The singers’ featured songs, “Nothing to My Name” (Yiwusuoyou) and “Descendants of the Dragon” (Long de chuanren) became unofficial anthems of the protesters. Hou was deeply involved in the protest by joining the hunger strike initiated by Liu Xiaobo and was one of the negotiators at the dawn of June 4th with the military. In an interview with Tiananmen student leader Wuer Kaixi, he emphasized the importance of singers in the movement: “The people who are most influential among young people are not (the dissident intellectuals) Fang Lizhi and Wei Jingsheng, but singers such as Cui Jian.” (Huang, 2001) In Hong Kong, Concert for Democracy in China was held for 12 hours nonstop to raise money for the protesters on May 27th. After the crackdown, music became an important means of commemorating the protests and preserving memories and protecting legacies against state propaganda and collective amnesia. Even new generations who were born after 1989 wrote songs in memory of the protest. -

Two Generations of Contemporary Chinese Folk Ballad Minyao 1994-2017

Two Generations of Contemporary Chinese Folk Ballad Minyao 1994-2017: Emergence, Mobility, and Marginal Middle Class A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC July 2020 By Yanxiazi Gao Thesis Committee: Byong Won Lee, Chairperson Frederick Lau (advisor) Ricardo D. Trimillos Cathryn Clayton Keywords: Minyao, Folk Ballad, Marginal Middle Class and Mobility, Sonic Township, Chinese Poetry, Nostalgia © Copyright 2020 By Yanxiazi Gao i for my parents ii Acknowledgements This thesis began with the idea to write about minyao music’s association with classical Chinese poetry. Over the course of my research, I have realized that this genre of music not only relates to the past, but also comes from ordinary people who live in the present. Their life experiences, social statuses, and class aspirations are inevitably intertwined with social changes in post-socialist China. There were many problems I struggled with during the research and writing process, but many people supported me along the way. First and foremost, I am truly grateful to my advisor Dr. Frederick Lau. His intellectual insights into Chinese music and his guidance and advice have inspired me to keep moving throughout the entire graduate study. Professor Ricardo Trimillos gave frequent attention to my academic performance. His critiques of conference papers, thesis drafts, and dry runs enabled this thesis to take shape. Professor Barbara Smith offered her generosity and support to my entire duration of study at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. -

Title the Cultural Politics of Introducing Popular Music Into China's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub The cultural politics of introducing popular music into China's Title music education Author(s) Ho, WC; Law, WW Citation Popular Music And Society, 2012, v. 35 n. 3, p. 399-425 Issued Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/175532 This is an electronic version of an article published in Popular Music And Society, 2012, v. 35 n. 3, p. 399-425. The Journal Rights article is available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03007766.2011.5679 16 1 The Cultural Politics of Introducing Popular Music into China’s Music Education The Cultural Politics of Introducing Popular Music into China’s Music Education Wai-Chung Ho and Wing-Wah Law Since embarking on its course of economic reform and opening up to the world in the late 1970s, China has moved from a planned economy to a socialist-market economy; the resultant social and cultural changes have been many, and are reflected in the country’s school music curriculum. This paper first introduces the historical background of popular music in the community and in school music in China in the twentieth century. Second, it explores the reform of music education that has, from the turn of the millennium, included popular music in school music education. This is followed by a discussion of the integration of popular music into the school curriculum in terms of how music education and cultural politics are shaped by the social and political relationships between: (i) contemporary cultural and social values and traditional Chinese ideologies; (ii) collectivism and individualism; and (iii) nationalism and globalism. -

Rock and Roll and Its Cultural Legacy in Post-Socialist China" (2013)

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College East Asian Languages and Cultures Department East Asian Languages and Cultures Department Honors Papers 2013 Rock and Roll and its Cultural Legacy in Post- Socialist China Cameron Ruscitti Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/eastasianhp Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ruscitti, Cameron, "Rock and Roll and its Cultural Legacy in Post-Socialist China" (2013). East Asian Languages and Cultures Department Honors Papers. 5. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/eastasianhp/5 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the East Asian Languages and Cultures Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Asian Languages and Cultures Department Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Rock and Roll and its Cultural Legacy in Post-Socialist China An Honors Thesis Presented by Cameron Ruscitti To The Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 3, 2013 Ruscitti 2 I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to: Professor Yibing Huang Professor Dale Wilson Professor Tek-wah King The Department of EALC CISLA Modern Sky Entertainment Peter Donaldson Jackie Zhang Mengyou Zhang and, of course, my family and friends Ruscitti 3 Introduction It has been said many times over that the current generation doesn’t need rock. -

Cui Jian: Extolling Idealism Yet Advocating for Freedom Through Rock Music in China Zhaoxi Liu Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Communication Faculty Research Communication Department Spring 2016 Cui Jian: Extolling Idealism Yet Advocating for Freedom Through Rock Music in China Zhaoxi Liu Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/comm_faculty Part of the Communication Commons Repository Citation Liu, Z. (2016). Cui Jian: Extolling idealism yet advocating for freedom through rock music in China. International Communication Research Journal, 51(1), 3-20. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cui Jian: Extolling Idealism Yet Advocating for Free- dom through Rock Music in China By Zhaoxi Liu Examining Cui Jian’s songs as text, this study attempted to provide a reading of its political meaning that is diferent from many previous studies. Through a textual analysis of the revolutionary symbols in four of Cui’s hits, this study found that the political meaning of Cui’s songs is much more nuanced than a simple oppositional message, as he simulta- neously endorses the Communist rule for its idealism and disavows it for its political suppression. Being China’s frst rocker, Cui Jian is politicized by the social discourse surrounding him as well as his own expressions, as he pursues his idealism and identity in the particular political and social context of China. Cui Jian (Cui is the last name) is known as “the Father of Chinese Rock ‘n Roll” (Ho, 2006; Jones, 1992; Matusitz, 2010). -

Bulletin CHINESE HISTORICAL SOCIETY of AMERICA | MARCH APRIL 2006 | VOL

Bulletin CHINESE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA | MARCH APRIL 2006 | VOL. 42, NO. 2 James Leong Mar/Apr Confronting My Roots 2006 APRIL 18 - AUGUST 20, 2006 CALENDAR OF CHSA CHSA FRANK H. YICK GALLERY EVENTS & EXHIBITS n 1956, artist James Leong March 30 Talk Story set sail for Norway, never to Family Panel I Artist Flo Oy I Wong discusses her family-orient- live again in his native San ed installation with her prolific Francisco. His work returns to siblings: writer Li Chinatown in the Keng Wong, poet exhibition James Nellie Wong, jour- Leong: Confronting nalist and author My Roots, opening William Wong, and April 18 at the Lai G. Webster. Chinese Historical CHSA Learning James Leong’s Tiananmen Center, 7 pm, free Society of America to the public. Museum and Learning Center. and feeling stifled by an overstimu- April 2 Chinese American Curated by Irene Poon Andersen, lating Beat-era North Beach art Voices Book Launch Party I Join co- the show features Leong’s most scene, Leong sought opportunities editors Judy Yung, Gordon Chang, recent paintings, which meld his to work and paint elsewhere. and Him Mark Lai in celebrating the guiding theme, nature, with the Following his graduation from the recent publication of Chinese American Voices. See article in issue of Chinese ethnic identity California College of Arts and Bulletin for more information. in America. Crafts, he received a Fulbright Chinese Culture Center, 750 Kearny, James Leong was born in Fellowship to live and study in 3rd Fl., San Francisco, 1 pm, free to 1929 in San Francisco Chinatown. -

TIANANMEN: CHINA's STRUGGLE for DEMOCRACY ITS PRELUDE, DEVELOPMENT, AFTERMATH, and Impacf

OccAsioNAl PApERS/ REpRiNTS SERiES iN CoNTEMpoRARY AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 2 - 1990 (97) TIANANMEN: CHINA'S STRUGGLE FOR , DEMOCRACY , •• ITS PRELUDE, DEVELOPMENT, AFTERMATH, AND IMPACT Edited by Winston L. Y. Yang and Marsha L. Wagner Scltool of LAw UNivERsiTy of 0 MARylANd. c ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Chih-Yu Wu Managing Editor: Chih-Yu Wu Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies, Korea University, Republic of Korea All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $18.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and $24.00 for Canada or overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS. Price for single copy of this issue: US $8.00.