Brhatkatha Studies: the Problem of an Ur-Text Author(S): Donald Nelson Source: the Journal of Asian Studies, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

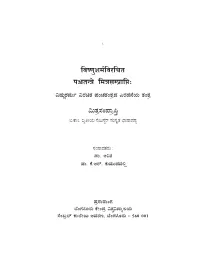

Mitrasamprapthi Preliminary

i ^GÈ8ZHB ^GD^09 QP9·¦R ^B¦J¿ºP^»f ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ )¶X¶À» ˶Ç˶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç· 2·Ç¦~º»À¥»¶Td¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶U¶ ¶Ç·¶2¶¶» X· #˶ X· 2À$d 2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ ¶··Ç9¶ ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇQ¡d2·¡ÀºI»$¤¶¶^ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» ii Blank iii ¤¶»»¶»Y ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» 2ÀºÇ¶ ¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» )¶X¶Àº À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ¶¶¥ ˶¶9¶~» ¶Ç¶}˶ ¥·Æ9¶´9À¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶·9¶¤¶¶»¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®À ·¶~º» ¶Ç¶}~» ¶J·P¶ °·9¶½ ¤¶¸¶¥º» ¤¶¿Â 9¶³¶¶C¶»2À4¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶»¶#˶¤¶§¶2¶¤·:À ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» & ¶U¶¤¶¶» #·¶2¶ °·9¶½ ¥·Æ¤¶ÄǶ2À4 #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ ¶2· 2À4®¶y¶Y®2À½QTX·#˶°·9¶½X·2À$d2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ #¤¶9À¶¶¤·¶9¶³¶» ¶Ç¶}˶ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶³¶» & 2¶Ä~»¶» ¶¶»¶½º9¶¶XÀ»»¤¶ÀǶ»$¨¶»ËÀºÀ À¾vJ·ÀRd '¶2¶» ¶~9¶³¶» ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» iv Blank v ¶Ç·¶2¶¶¶»Y ¶Ç¶}˶ ·±Ë¶ ¶2·¶9¶³¶¢£ ,Ç·¶ 2¶··±Ë¶¤¶¼ ¥§¶¦¶®¶y¤·¶»¶»%Ç˶°¶·±Ë¶¶#¶»¶¤¶¼%Ç9¶½#˶Ç˶ ¶¶»Ë¶¤·:À & 2¶··±Ë¶ 9¶Ç¶9¶³¶¢£ ¶¤¶»»5¤·¶ ,Ƕ» 2¶Ä~ ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶vÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» Àº §ÀÁ2¶¬`2¶ ¤¶ª¶ÆǶ J·9À z¶»¤¶ÇËÀ ¦~º» À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ˶¶9¶~9À ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» ,Ƕ» ·9¶¤¶¶» ¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®Ë¶» %¶¶ ¶Ç·¶·2·»Æ¤¶¶»¶¤¶»9À¤¶±®Ë¶»¤¶»ÇX¶´»¶½C¶À»ÇËÀ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶´9À #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ & ¶U¶¤¶¶»®¶y¶Y¶¡·:À ¤¶»½ ¶Ç¶}˶ ¶U¶·9¶¤¶¶» 2¶Äª¶|·¶ #2·X¶¥» ¤·¶1·® ¶2¶Q¶Y®¶»¤¶X·¶»·2¶¶¤¶¸ ¥º»%¤¶¶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d )Çz2¶Ä~»Ç¶®¦º2¶¶¡·:À &¶U¶2À4JÀ¶£¨Ç9d°ÂdÀ°¶¢X·¶¥ºd2¶»¤¶¸d ¶M¸ ¤¶»Ë¶» X· #ÇI· %¤¶¶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d ¶¼¶2¶¶ $Ç9¶£ #¶»¤·¶¤¶¶» »·¤¶Ë·: ®¦º2¶¶¡·:À & ¶U¶¶¼¶2¶¶ ¶C¶À»¢£ #Àº2¶ 2¶Ä~9¶³¶ ¶°·»¤¶¶» ¶XÀ»¡·:À & )¡·£ 9¶Ç¶2¶Ë¶ÄÆ9¶´9¶½·¤¶¼$·¸:¶»ËÀº¤À & ¶U¶¶ 2¶¶X¶ -

Kanvas (73 BC – 28 BC) Cheti Dynasty (Kalinga) Satavahanas

Kanvas (73 BC – 28 BC) As per the puranas, there were four kings of the Kanva dynasty namely, Vasudeva, Bhumimitra, Narayana and Susarman. The Kanvas were Brahmins. The Magadha Empire had diminished by this time considerably. Northwest region was under the Greeks and parts of the Gangetic plains were under different rulers. The last Kanva king Susarman was killed by the Satavahana (Andhra) king. Cheti Dynasty (Kalinga) The Cheti or Chedi dynasty emerged in Kalinga in the 1st century BC. The Hathigumpha inscription situated near Bhubaneswar gives information about it. This inscription was engraved by king Kharavela who was the third Cheti king. Kharavela was a follower of Jainism. Other names of this dynasty are Cheta or Chetavamsa, and Mahameghavahana. Satavahanas The Satavahana rule is believed to have started around the third century BC, in 235 BC and lasted until the second century AD. Some experts believe their rule started in the first century BC only. They are referred to as Andhras in the Puranas. The Satavahana kingdom chiefly comprised of modern-day Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra. At times, their rule also included parts of Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Their capital cities varied at different times. Pratishthana (Paithan) and Amaravati were its capitals. Simuka founded the dynasty. They were the first native Indian rulers to issue their own coins with the portraits of the rulers. This practice was started by Gautamiputra Satakarni who derived the practice from the Western Satraps after defeating them. The coin legends were in Prakrit language. Some reverse coin legends are in Telugu, Tamil and Kannada. -

Türkġye Cumhurġyetġ Ankara Ünġversġtesġ Sosyal Bġlġmler Enstġtüsü Doğu Dġllerġ Ve Edebġyatlari Anabġlġmdali

TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ DOĞU DĠLLERĠ VE EDEBĠYATLARI ANABĠLĠMDALI HĠNDOLOJĠ BĠLĠM DALI HĠNT SĠNEMASININ EDEBĠ KAYNAKLARI: KATHĀSARĠTSĀGARA ÖRNEĞĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Hatice Ġlay Karaoğlu ANKARA-2019 TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ DOĞU DĠLLERĠ VE EDEBĠYATLARI ANABĠLĠMDALI HĠNDOLOJĠ BĠLĠM DALI HĠNT SĠNEMASININ EDEBĠ KAYNAKLARI: KATHĀSARĠTSĀGARA ÖRNEĞĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Hazırlayan Hatice Ġlay Karaoğlu Tez DanıĢmanı Prof. Dr. Korhan Kaya ANKARA-2019 TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ DOĞU DĠLLERĠ VE EDEBĠYATLARI ANABĠLĠMDALI HĠNDOLOJĠ BĠLĠM DALI HĠNT SĠNEMASININ EDEBĠ KAYNAKLARI: KATHĀSARĠTSĀGARA ÖRNEĞĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Tez DanıĢmanı: Prof. Dr. Korhan Kaya Tez Jüri Üyerileri: Adı Soyadı Ġmzası ………………………… ..…………………………. …………………………. …………………………… …………………………. …………………………… …………………………. ……………………………. …………………………. ……………………………. Tez Sınav Tarihi………………… TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE Bu belge ile bu tezdeki bütün bilgilerin akademik kurallara ve etik davranıĢ ilkelerine uygun olarak toplanıp sunulduğunu beyan ederim. Bu kural ve ilkelerin gereği olarak, çalıĢmada bana ait olmayan tüm veri, düĢünce ve sonuçları andığımı ve kaynağını gösterdiğimi ayrıca beyan ederim. (24/06/2019) Tezi Hazırlayan Öğrencinin Adı ve Soyadı Hatice Ġlay Karaoğlu Ġmzası ÖNSÖZ Bir sinema filmi, yazılı bir eserin konusundan yararlanabildiği gibi konunun eserdeki sunumundan da yararlanabilmektedir. Burada bahsi geçen sunum, hikâyenin -

Sanskrit and Prakrit*

CHAPTER 1—SANSKRIT AND PRAKRIT* Sanskrit and Prakrit. THE WORD MAHARASHTRA OCCURS FAIRLY LATE IN SANSKRIT LITERATURE and its earliest occurrence does not go beyond the early centuries of the Christian Era. But particular parts of the region which comprise the State of Maharashtra appear to have been colonized by speakers of Indo-Aryan at a much earlier age. Thus while Vidarbha by itself occurs not earlier than in the Maha- bharata and the Puranas, Vidarbhi-Kaundinya ' name of a preceptor ' occurs in the Satapatha Brahmana and Vaidarbha ' name of a king of the Vidarbhas ' occurs in the Aitareya Brahmana. Thus, towards the close of the Brahmana period of Vedic literature Vidarbha seems to have been colonized by the speakers of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan, and a new secular literature seems to have grown there developing certain regional features in its style to have been specifically recognized as the Vaidarbhi Riti or Vaidarbhi style, in opposition to similar regional dictions or styles referred to as Gaudi, Panchali, Lati, Avantika and Magadhi. These names are indicative of the fact that there was a growing secular literature which developed certain regional styles, one of which, the Vaidarbhi was highly praised by critical readers of literature and style. The development of Middle Indo-Aryan literature which appears to have taken place alongside that of Sanskrit also gives us names of Middle Indo-Aryan languages which are geographically oriented. The earliest Prakrit grammars, those of Chanda and Vararuchi, probably not later than the 2nd century A. D., already recognize Maharashtri as the Prakrit par excellence, and is the first to be analysed and described in their grammatical treatises. -

A Musical Marriage

A Musical Marriage Durga Bhagvat Introduction The legend of the 'musical' marriage of the future Gandharva monarch, Naravahanadatta, (son of the famous Udayana, King of Vatsa, and the re nowned beauty Vasavadatta) to the Gandharva maiden, Gandharvadatta, is both unique and entertaining. The legend is found in the Brihat Katha-Shloka-Samgraha by Budha svamin of Kashmir. The only p.ublished edition of the first seventeen chapt_,ers of the work, with notes and translation in French, was that of Felix Lacote. It was published in Paris in 1 908. Lacote has also written an analysis of the same work and compared it to other important versions of the Brihat. Katha by Gunadhya. The work, Essai sur Gunadhya et Ia Brihat Katha (Paris, 1 908). is an exhaustive study of 335 pages. The legend of Naravahanadatta and Gandharvadatta is given in the main in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth chapters of the Brihat Katha-Shloka-Samgraha. Before presenting the legend it would be appropriate to consider very briefly certain important data about the Brihat Katha of Gunadhya, and its versions, inclusive of the work of Budhasvamin. The original Brihat Katha of Gunadhya was reckoned by eminent literary figures in medieval India to be as important as the great epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Gunadhya thus occupied the revered position accorded to Vyasa and Valmiki. He was at the court of King Satavahana of Pratishthana and is supposed to have lived either in the second or the third century of the Chris~ian era . Gunadhya's work was written in the Paishachi language, a variety of Prakrit, considered to be spoken by barbarians and goblins. -

SOCIAL SCIENCE (Revised Textbook)

Government of Karnataka SOCIAL SCIENCE (Revised Textbook) 8 EIGHTH STANDARD KARNATAKA TEXT BOOK SOCIETY (R) 100 Feet Ring Road, Banashankari, 3rd stage Bengaluru-85. I Preface The Textbook Society, Karnataka has been engaged in producing new textbooks according to the new syllabi prepared which in turn are designed based on NCF – 2005 since June 2010. Textbooks are prepared in 11 languages; seven of them serve as the media of instruction. From standard 1 to 4 there is the EVS and 5th to 10th there are three core subjects namely mathematics, science and social science. NCF – 2005 has a number of special features and they are: • Connecting knowledge to life activities • Learning to shift from rote methods • Enriching the curriculum beyond textbooks • Learning experiences for the construction of knowledge • Making examinations flexible and integrating them with classroom experiences • Caring concerns within the democratic policy of the country • Make education relevant to the present and future needs. • Softening the subject boundaries-integrated knowledge and the joy of learning. • The child is the constructor of knowledge The new books are produced based on three fundamental approaches namely. Constructive approach, Spiral Approach and Integrated approach The learner is encouraged to think, engage in activities, master skills and competencies. The materials presented in these books are integrated with values. The new books are not examination oriented in their nature. On the other hand they help the learner in the total development of his/her personality, thus help him/her become a healthy member of a healthy society and a productive citizen of this great country, India. -

A History of Sanskrit Literature

A History of Sanskrit Literature Author: Arthur A. MacDonell Project Gutenberg's A History of Sanskrit Literature, by Arthur A. MacDonell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A History of Sanskrit Literature Author: Arthur A. MacDonell Release Date: December 5, 2012 [EBook #41563] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE *** Produced by Jeroen Hellingman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net/ for Project Gutenberg (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) A HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE By ARTHUR A. MACDONELL, M. A., Ph. D. Of Corpus Christi College, Oxford Boden Professor of Sanskrit and Fellow of Balliol New York D. Appleton and Company 1900 PREFACE It is undoubtedly a surprising fact that down to the present time no history of Sanskrit literature as a whole has been written in English. For not only does that literature possess much intrinsic merit, but the light it sheds on the life and thought of the population of our Indian Empire ought to have a peculiar interest for the British nation. Owing chiefly to the lack of an adequate account of the subject, few, even of the young men who leave these shores every year to be its future rulers, possess any connected information about the literature in which the civilisation of Modern India can be traced to its sources, and without which that civilisation cannot be fully understood. -

Encyclopedia-Of-Hinduism-Pt.02.Pdf

Jyoti, Swami Amar 215 J birth and rebirth but remains alive. Most Shaivite Jnanasambanthar See SAMBANTHAR. traditions, and the VEDANTA of SHANKARA, accept the possibility of jivanmukti (living liberation). Other Hindu traditions, such as VAISHNAVISM, do jnana yoga See BHAGAVAD GITA. not accept the concept; they insist that full libera- tion occurs only at death. Neither Jains nor Sikhs believe in jivanmukti. jnanedriya See SAMKHYA. Historically, many of the earlier philosophies of India, such as SAMKHYA, had no place for the idea. A strict reading of YOGA SUTRA would not Jnaneshvara (1275–1296) poet-saint allow for it either. Jnaneshvara was a Vaishnavite (see VAISHNAVISM) poet-saint from Maharashtra, who wrote hymns Further reading: Andrew O. Fort, Jivanmukti in Transfor- of praise to VITHOBA and RUKMINI, the Maha- mation: Embodied Liberation in advaita and Neo-Vedanta rashtran forms of KRISHNA and RADHA who are (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998). worshipped at Pandharpur. He is most famous for his commentary on the BHAGAVAD GITA writ- ten in old Marathi, a beloved and revered text jivatman See VEDANTA. in Maharashtra. It is said that Jnaneshvara died at the age of 22, at Alandi on the Krishna River. This is now an important pilgrimage site; his jnana shrine is visited there at the time of the poet’s Jnana (from the root jna, “to know”) literally death in November. means “knowledge” but is better translated as “gnosis” or “realization.” Specifically, it is the Further reading: P. V. Bobde, trans., Garland of Divine knowledge of the unity between the highest real- Flowers: Selected Devotional Lyrics of Saint Jnanesvara ity, or BRAHMAN, and the individual self, or JIVATMAN. -

The Monomyth of Vikramaditya

SMART MOVES JOUNRNAL IJELLH e-ISSN 2582-3574 p-ISSN 2582-4406 VOL 8, ISSUE 3, MARCH 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24113/ijellh.v8i3.10626 The Monomyth of Vikramaditya Dr. Shreeja Tripathi Sharma Assistant Professor of English Department of Higher Education Government of Madhya Pradesh India [email protected] Abstract The legendary king Vikramaditya, revered in India as an epitome of valour and justice is an enigmatic paradox of historical reality and mythic truth. Despite several textual references, his historical presence, is ambiguous and lacking in epigraphic evidence. The credibility of the Vikramaditya legend has often been disregarded by factual historians sniffing and screening out elements of fantasy in the tales. However, the eternal spirit of Vikramaditya is beyond what eyes can see and beyond what the mind can prove. While from a historical standpoint an accurate account of the King would inevitably remain incomplete, Vikramaditya, the archetypal hero is absolute and ephemeral. His identity as an archetypal the hero, typically confirms to the archetypal structure of the ‘mono-myth’ and is analogous to mythic parallels of several cultures. This paper undertakes to examine king Vikramaditya with respect to the archetypal manifestation of his existence, in the mythic perspective. Keywords: Vikramaditya, Vetaal Panchavinshati, Archetypal Hero, Monomyth The relationship between the historicity of Vikramaditya and the reality of his legendary story is complex and disputed. There are two broad categories of theories centred www.ijellh.com 322 SMART MOVES JOUNRNAL IJELLH e-ISSN 2582-3574 p-ISSN 2582-4406 VOL 8, ISSUE 3, MARCH 2020 around the legendary king. -

Sanskrit Literary Criticism - Basic Terminologies in Sanskrit Literary Criticism Related to Kavisiksa

1 SREE SANKARACHARYA UNIVERSITY OF SANSKRIT KALADY – 683 574. CREDIT COURSES FOR M. PHIL / PH.D. Approved by Research Council and theBoard of Studies 2 CONTENTS 1. SSS 101 - KAVISIKSA: WORKSHOP CRITICISM IN SANSKRIT Dr. Reeja B. Kavanal 2. SSS 102-LOKAYATA – PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICS Dr. P. K. Dharmarajan 3. SSS 103 - WOMEN IN GRHYASUTRAS Dr. K. G. Ambika 4. SSS 104 -READINGS OF CLASSICS: CONTEMPORARY READINGS ON THE WORKS OF KALIDASA Dr. T. Vasudevan 5. SSS 105- Core Course – RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND TECTUAL CRITICISM Dr. N. V. Kunjamma 6. SSS 106 – SANSKRIT LITERATURE AS A SOURCE MATERIAL FOR THE STUDY OF INDIAN CULTURE. Dr. K.M. Sangamesan 7. SSS 107 - ENVIRONMENTAL WISDOM IN SANSKRIT Dr. K.M. Sangamesan 8. SSS 108 - MANUSCRIPTOLOGY AND TEXTUAL CRITICISM Dr. P. V. Narayanan 9. SSS 109 - ABHINAVAGUPTA’S AESTHETICS Dr. K. M. Sangamesan 10. SSS 110 - SANSKRIT SANDESAKAVYAS FOR HISTORICAL STUDIES Dr. K. V. Ajithkumar 11. SSS 111 - PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN ANCIENT INDIA Dr. P. V. Narayanan 12. SSS 112- YASKA’S NIRUKTA AND THE INTERPRETATION OF VEDA Dr. K. G. Ambika 13. SSS 113- SANSKRIT HISTORIOGRAPHY Dr. P. K. Dharmarajan 14. SSS 114- ANCIENT INDIAN MATHEMATICS AND ASTRONOMY Dr. V. R.Muralidharan 15. SSS 115- SANDHI AND SANDHYANGAS IN SANSKRIT PLAYS Dr. T. Mini 16. SSS 116- SANSKRIT LANGUAGE AND KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS Dr. P. K. Dharmarajan 17. SSS 117- INDIAN POETICS AND MODERN TEXTS Dr. T. Vasudevan 18. SSS 118- INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH METHODS Dr. T. Vasudevan 19. SSS 119- SANSKRIT FOR LITERARY AND CULTURAL STUDIES Dr. T. Vasudevan 20. SSS 120- WOMEN IN INDIAN EPICS Dr. -

![NCERT Notes: Satavahana Dynasty - Post Mauryan Period [Ancient Indian History Notes for UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4981/ncert-notes-satavahana-dynasty-post-mauryan-period-ancient-indian-history-notes-for-upsc-7684981.webp)

NCERT Notes: Satavahana Dynasty - Post Mauryan Period [Ancient Indian History Notes for UPSC]

NCERT Notes: Satavahana Dynasty - Post Mauryan Period [Ancient Indian History Notes For UPSC] The Sunga dynasty came to an end in around 73 BC when their ruler Devabhuti was killed by Vasudeva Kanva. The Kanva dynasty then ruled over Magadha for about 45 years. Around this time, another powerful dynasty, the Satavahanas came to power in the Deccan area. The term "Satvahana" originated from the Prakrit which means " driven by seven" which is an implication of the Sun God's chariot that is driven by seven horses as per the Hindu mythology. NCERT notes on important topics for the UPSC IAS aspirants. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like bank PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on. This article talks about Post-Mauryan India with a particular focus on the Satavahana Dynasty. Origin & Development of Satavahana dynasty The first king of the Satavahana dynasty was Simuka. Before the emergence of the Satavahana dynasty, a brief history of the other dynasties are mentioned below: Kanvas (73 BC – 30 BC) ● As per the Puranas, there were four kings of the Kanva dynasty namely, Vasudeva, Bhumimitra, Narayana and Susarman. ● The Kanvas were Brahmins. ● The Magadha Empire had diminished by this time considerably. ● The Northwest region was under the Greeks and parts of the Gangetic plains were under different rulers. ● The last Kanva king Susarman was killed by the Satavahana (Andhra) king. Cheti Dynasty ● The Cheti or Chedi dynasty emerged in Kalinga in the 1st century BC. ● The Hathigumpha inscription situated near Bhubaneswar gives information about it. ● This inscription was engraved by king Kharavela who was the third Cheti king. -

Narratives Across Borders

Narratives Across Borders Narratives Across Borders By Manju Jaidka Narratives Across Borders By Manju Jaidka This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Manju Jaidka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8811-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8811-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Telling the Tale Chapter I ...................................................................................................... 9 Immortal Classics The Panchatantra: Stories with a Lesson The Kathasaritsagar The Epics: Immortal Tales The Ramayana The Mahabharata 1001 Arabian Nights: Revisions and Re-workings Oedipus Rex: The Courage to Know Chapter II ................................................................................................... 53 Recurrent Patterns (i) The Wanderer Divine Comedy: The Soul in Search of Light Don Quixote: Of Picaros and Puzzles Huckleberry Finn: The Journey Continues (ii)