A Peep Into the Early History of India: from the Foundation of the Maurya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

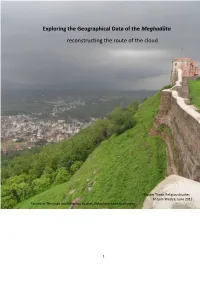

Exploring the Geographical Data of the Meghadūta Reconstructing the Route of the Cloud

Exploring the Geographical Data of the Meghadūta reconstructing the route of the cloud. Master Thesis ReligiousStudies Mirjam Westra, June 2012 Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 PART I: Kālidsa ‘s religio- geocultural imaginaire: The itinerary of the cloud from Rmagiri to Da.apura. 7 Introduction 7 Rmagiri 8 The land of Mla 11 The mountain mrakūa 13 The river Rev at the foot of the Vindhya Mountains 15 Da.ra and its capital Vidi. on the Vetravatī 16 Nīcair-hill 18 The land of Avanti and its rivers 20 The city of Vi.l and the Mahkla temple 21 Devagiri 23 Da.apura 25 Part II: Kālidsa’s mythological imaginaire: The itinerary of the cloud from Brahmvarta to the city of Alak 27 Introduction 27 Brahmvarta & Kuruketra 27 Sarvasvatī 31 Kanakhala and the holy river Ganges 33 Himlaya and the Source of the Ganges 35 iva’s footprint 36 Himlaya and the Krauca Pass 39 Mount Kailsa and Lake Mnasa 41 The celestial city of Alak 43 Conclusion 44 Appendix A: list of Geographical data of the Meghadūta 47 Appendix B: The itinerary of the cloud from Rmagiri to Da.apura 48 Appendix C: Detailed map of the itinerary of the cloud from Rmagiri to Da.apura 49 Appendix D: The itinerary of the cloud from Brahmvarta to Alak, mount Kailsa 51 References 52 2 Introduction The Meghadta tells about a certain Yaka who was banished by his master Kubera from Alak, city of the gods in the Himlayan mountains, for a period of one year after he was grossly neglectful of his duty. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Research Paper Sociology Vamana–Trivikrama in Badami Chalukya Sculpture

Volume : 2 | Issue : 9 | Sept 2013 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Research Paper Sociology Vamana–Trivikrama In Badami Chalukya Sculpture Smt. Veena Muddi Research Scholar,Dept of Ancient Indian History and Epigraphy, Karnatak University, Dharwad Introduction Padma Purana Until the time of Vikramaditya I the rulers of the Chalukya dynasty of Vishnu was born as a son of Aditi. Knowing about sacrifice being per- Badami (543-757 CE) were the inclined towards Vaishnavism. The re- formed by Bali, Vishnu went to the place of sacrifice along with eight cords of Mangalesa (Padigar:2010:9-11,12-15) and Polekesi II (Padi- sages. Vamana told the reason for his arrival and asked for a piece of gar:2010:42-45) are vocal in describing them as parama-bhagavatas, land measured by his three steps. Sukracharya advised Bali not to grant ‘great devotees of Vishnu’. The fact that two of the four caves excavated Vamana’s request. But Bali would not listen to his guru. He washed the by them at their capital Badami, all of them dating from pre-620 CE feet of Lord and granted Vamana’s wish. After that Lord abandoned his period, are dedicated to god Vishnu is further evidence of the situation. dwarfish form, took the body of Vishnu, covered the whole universe In 659 CE Virkamaditya I was initiated into Mahesvara brand of Saivism and sent Bali to netherworld.(Bhatt:1991:3211-3215) through a ritual called Sivamandala-diksha. (Padigar:2010:67-70) Henceforth he came to be called a parama-Mahesvara, ‘a great devo- Narada Purana tee of Mahesvara or Siva’. -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

Cape Comorin Volume II Issue II July 2020

ISSN: 2582-1962 Cape Comorin Volume II Issue II July 2020 An International Multidisciplinary Double-Blind Peer-reviewed Research Journal Maurya Dynasty. Myth, Legend or History Daya Dissanayake, Novelist, Poet and Blogger, Udumulla Road, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka Abstract: Over the past two centuries we have created a Maurya dynasty, or which should have been called a Chandragupta dynasty. Though Rama was deified, and the deification extended to Hanuman and Valmiki as we find at Ram Tirth in Amritsar, even Asoka Maurya has not been deified yet, leaving us the freedom to discuss the historicity of the Mauryas. In India Buddha and Mahavira have become founders of two great religious traditions. They are accepted as historical characters, and their biographies cannot be questioned, because it would amount to questioning the faith of people. About other people we come across in the long history of India, specially those who are believed to have lived Before the Common Era, we do not have any solid evidence of writing or archaeological remains to determine their historicity, chronology or about their lives. Their biographies are accepted by many as history, by a few as legends, and could even be considered myths only. We call him Chandragupta assuming he is the same Sandracottus of the Greeks. Bindusara is claimed to be his son, identified as Amitrocades. Aśoka/Devanampiya/Piyadassi is accepted as his grandson, but never mentioned by the Greeks, by any name, Greek or Indian. Chandragupta‟s biography was created by the British, selectively picking from secondary and tertiary Greek sources, and from a drama produced about eight centuries after Chandragupta. -

The Heritage of India Series

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES T The Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, t [ of Dornakal. E-J-J j Bishop I J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.). Already published. The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Asoka. J. M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting. PRINCIPAL PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A., D.Litt. The Karma-MImamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Hymns of the Tamil Saivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Rabindranath Tagore. E. J. THOMPSON, B.A., M.C. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gotama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Subjects proposed and volumes under Preparation. SANSKRIT AND PALI LITERATURE. Anthology of Mahayana Literature. Selections from the Upanishads. Scenes from the Ramayana. Selections from the Mahabharata. THE PHILOSOPHIES. An Introduction to Hindu Philosophy. J. N FARQUHAR and PRINCIPAL JOHN MCKENZIE, Bombay. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Sankara's Vedanta. A. K. SHARMA, M.A., Patiala. Ramanuja's Vedanta. The Buddhist System. FINE ART AND MUSIC. Indian Architecture. R. L. EWING, B.A., Madras. Indian Sculpture. Insein, Burma. BIOGRAPHIES OF EMINENT INDIANS. Calcutta. V. SLACK, M.A., Tulsi Das. VERNACULAR LITERATURE. and K. T. PAUL, The Kurral. H. A. POPLBY, B.A., Madras, T> A Calcutta M. of the Alvars. -

Mitrasamprapthi Preliminary

i ^GÈ8ZHB ^GD^09 QP9·¦R ^B¦J¿ºP^»f ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ )¶X¶À» ˶Ç˶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç· 2·Ç¦~º»À¥»¶Td¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶U¶ ¶Ç·¶2¶¶» X· #˶ X· 2À$d 2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ ¶··Ç9¶ ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇQ¡d2·¡ÀºI»$¤¶¶^ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» ii Blank iii ¤¶»»¶»Y ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» 2ÀºÇ¶ ¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» )¶X¶Àº À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ¶¶¥ ˶¶9¶~» ¶Ç¶}˶ ¥·Æ9¶´9À¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶·9¶¤¶¶»¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®À ·¶~º» ¶Ç¶}~» ¶J·P¶ °·9¶½ ¤¶¸¶¥º» ¤¶¿Â 9¶³¶¶C¶»2À4¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶»¶#˶¤¶§¶2¶¤·:À ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» & ¶U¶¤¶¶» #·¶2¶ °·9¶½ ¥·Æ¤¶ÄǶ2À4 #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ ¶2· 2À4®¶y¶Y®2À½QTX·#˶°·9¶½X·2À$d2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ #¤¶9À¶¶¤·¶9¶³¶» ¶Ç¶}˶ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶³¶» & 2¶Ä~»¶» ¶¶»¶½º9¶¶XÀ»»¤¶ÀǶ»$¨¶»ËÀºÀ À¾vJ·ÀRd '¶2¶» ¶~9¶³¶» ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» iv Blank v ¶Ç·¶2¶¶¶»Y ¶Ç¶}˶ ·±Ë¶ ¶2·¶9¶³¶¢£ ,Ç·¶ 2¶··±Ë¶¤¶¼ ¥§¶¦¶®¶y¤·¶»¶»%Ç˶°¶·±Ë¶¶#¶»¶¤¶¼%Ç9¶½#˶Ç˶ ¶¶»Ë¶¤·:À & 2¶··±Ë¶ 9¶Ç¶9¶³¶¢£ ¶¤¶»»5¤·¶ ,Ƕ» 2¶Ä~ ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶vÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» Àº §ÀÁ2¶¬`2¶ ¤¶ª¶ÆǶ J·9À z¶»¤¶ÇËÀ ¦~º» À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ˶¶9¶~9À ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» ,Ƕ» ·9¶¤¶¶» ¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®Ë¶» %¶¶ ¶Ç·¶·2·»Æ¤¶¶»¶¤¶»9À¤¶±®Ë¶»¤¶»ÇX¶´»¶½C¶À»ÇËÀ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶´9À #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ & ¶U¶¤¶¶»®¶y¶Y¶¡·:À ¤¶»½ ¶Ç¶}˶ ¶U¶·9¶¤¶¶» 2¶Äª¶|·¶ #2·X¶¥» ¤·¶1·® ¶2¶Q¶Y®¶»¤¶X·¶»·2¶¶¤¶¸ ¥º»%¤¶¶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d )Çz2¶Ä~»Ç¶®¦º2¶¶¡·:À &¶U¶2À4JÀ¶£¨Ç9d°ÂdÀ°¶¢X·¶¥ºd2¶»¤¶¸d ¶M¸ ¤¶»Ë¶» X· #ÇI· %¤¶¶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d ¶¼¶2¶¶ $Ç9¶£ #¶»¤·¶¤¶¶» »·¤¶Ë·: ®¦º2¶¶¡·:À & ¶U¶¶¼¶2¶¶ ¶C¶À»¢£ #Àº2¶ 2¶Ä~9¶³¶ ¶°·»¤¶¶» ¶XÀ»¡·:À & )¡·£ 9¶Ç¶2¶Ë¶ÄÆ9¶´9¶½·¤¶¼$·¸:¶»ËÀº¤À & ¶U¶¶ 2¶¶X¶ -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Peshawar Museum Is a Rich Repository of the Unique Art Pieces of Gandhara Art in Stone, Stucco, Terracotta and Bronze

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Peshawar Museum is a rich repository of the unique art pieces of Gandhara Art in stone, stucco, terracotta and bronze. Among these relics, the Buddhist Stone Sculptures are the most extensive and the amazing ones to attract the attention of scholars and researchers. Thus, research was carried out on the Gandharan Stone Sculptures of the Peshawar Museum under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, the then Director of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP, currently Vice Chancellor Hazara University and Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar. The Research team headed by the authors included Messrs. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Muhammad Ashfaq, Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Muhammad Zahir, Asad Raza, Shahid Khan, Muhammad Imran Khan, Asad Ali, Muhammad Haroon, Ubaidullah Afghani, Kaleem Jan, Adnan Ahmad, Farhana Waqar, Saima Afzal, Farkhanda Saeed and Ihsanullah Jan, who contributed directly or indirectly to the project. The hard working team with its coordinated efforts usefully assisted for completion of this research project and deserves admiration for their active collaboration during the period. It is great privilege to offer our sincere thanks to the staff of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums Govt. of NWFP, for their outright support, in the execution of this research conducted during 2002-06. Particular mention is made here of Mr. Saleh Muhammad Khan, the then Curator of the Peshawar Museum, currently Director of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP. The pioneering and relevant guidelines offered by the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP deserve appreciation for their technical support and ensuring the availability of relevant art pieces. -

Kanvas (73 BC – 28 BC) Cheti Dynasty (Kalinga) Satavahanas

Kanvas (73 BC – 28 BC) As per the puranas, there were four kings of the Kanva dynasty namely, Vasudeva, Bhumimitra, Narayana and Susarman. The Kanvas were Brahmins. The Magadha Empire had diminished by this time considerably. Northwest region was under the Greeks and parts of the Gangetic plains were under different rulers. The last Kanva king Susarman was killed by the Satavahana (Andhra) king. Cheti Dynasty (Kalinga) The Cheti or Chedi dynasty emerged in Kalinga in the 1st century BC. The Hathigumpha inscription situated near Bhubaneswar gives information about it. This inscription was engraved by king Kharavela who was the third Cheti king. Kharavela was a follower of Jainism. Other names of this dynasty are Cheta or Chetavamsa, and Mahameghavahana. Satavahanas The Satavahana rule is believed to have started around the third century BC, in 235 BC and lasted until the second century AD. Some experts believe their rule started in the first century BC only. They are referred to as Andhras in the Puranas. The Satavahana kingdom chiefly comprised of modern-day Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra. At times, their rule also included parts of Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Their capital cities varied at different times. Pratishthana (Paithan) and Amaravati were its capitals. Simuka founded the dynasty. They were the first native Indian rulers to issue their own coins with the portraits of the rulers. This practice was started by Gautamiputra Satakarni who derived the practice from the Western Satraps after defeating them. The coin legends were in Prakrit language. Some reverse coin legends are in Telugu, Tamil and Kannada. -

Notes on the Yuezhi - Kushan Relationship and Kushan Chronology”, by Hans Loeschner

“Notes on the Yuezhi - Kushan Relationship and Kushan Chronology”, by Hans Loeschner Notes on the Yuezhi – Kushan Relationship and Kushan Chronology By Hans Loeschner Professor Michael Fedorov provided a rejoinder1 with respect to several statements in the article2 “A new Oesho/Shiva image of Sasanian ‘Peroz’ taking power in the northern part of the Kushan empire”. In the rejoinder Michael Fedorov states: “The Chinese chronicles are quite unequivocal and explicit: Bactria was conquered by the Ta-Yüeh-chih! And it were the Ta-Yüeh-chih who split the booty between five hsi-hou or rather five Ta-Yüeh-chih tribes ruled by those hsi-hou (yabgus) who created five yabguates with capitals in Ho-mo, Shuang-mi, Hu-tsao, Po-mo, Kao-fu”. He concludes the rejoinder with words of W.W. Tarn3: “The new theory, which makes the five Yüeh- chih princes (the Kushan chief being one) five Saka princes of Bactria conquered by the Yüeh- chih, throws the plain account of the Hou Han shu overboard. The theory is one more unhappy offshoot of the elementary blunder which started the belief in a Saka conquest of Greek Bactria”.1 With respect to the ethnical allocation of the five hsi-hou Laszlo Torday provides an analysis with a result which is in contrast to the statement of Michael Fedorov: “As to the kings of K’ang- chü or Ta Yüeh-shih, those chiefs of foreign tribes who acknowledged their supremacy were described in the Han Shu as “lesser kings” or hsi-hou. … The hsi-hou (and their fellow tribespeople) were ethnically as different from the Yüeh-shih and K’ang-chü as were the hou… from the Han.