Monument to a to a Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition BY JENNIFER CLARK The seven-person jury seated around a table in the Old Courthouse with competition advisor George Howe in 1947. The jury met twice to assess designs and decide what the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial would look like. The designs included far more than a memorial structure. A landscaped 90-acre park, various structures, water features, a campfire theater, museum buildings, and restaurants were also part of the designs. (Image: National Park Service, Gateway Arch National Park) 8 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2018 Today it is hard to conceive of any monument Saint Louis Art Museum; Roland A. Wank, the chief that could represent so perfectly St. Louis’ role architect of the Tennessee Valley Authority; William in westward expansion as the Gateway Arch. The W. Wurster, dean of architecture at MIT; and Richard city’s skyline is so defined by the Arch that it J. Neutra, a well-known modernist architect. George seems impossible that any other monument could Howe was present for the jury’s deliberations and stand there. However, when the Jefferson National made comments, but he had no vote. Expansion Memorial (JNEM) was created by LaBeaume created a detailed booklet for the executive order in 1935, no one knew what form competition to illustrate the many driving forces the memorial would take. In 1947, an architectural behind the memorial and the different needs it was competition was held, financed by the Jefferson intended to fulfill. Concerns included adequate National Expansion Memorial Association, parking, the ability of the National Park Service a nonprofit agency responsible for the early to preserve the area as a historic site, and the development of the memorial idea. -

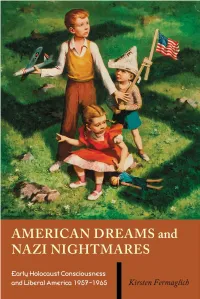

Fermaglich's I-Xiv-123

Fermaglich: American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares page i American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares Fermaglich: American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares page ii Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor Kirsten Fermaglich Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: “How Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Early Holocaust Consciousness and Liberal Camps as Jewish Socializing Experiences America, 1957–1965 Ori Z. Soltes Andrea Greenbaum, editor Fixing the World: Jewish American Painters Jews of South Florida in the Twentieth Century Sylvia Barack Fishman Gary P. Zola, editor Double or Nothing: Jewish Families and The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Mixed Marriages Jacob Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Jewry George M. Goodwin and Ellen Smith, David Zurawik editors The Jews of Prime Time The Jews of Rhode Island Ranen Omer-Sherman Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, Diaspora and Zionism in American Jewish editors Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, editors Jews of Brooklyn Michael E. Staub, editor The Jewish 1960s: An American Sourcebook Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, editors Judah M. Cohen Women and American Judaism: Historical Through the Sands of Time: A History of Perspectives the Jewish Community of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands Annelise Orleck, with photographs by Elizabeth Cooke Naomi W. Cohen The Soviet Jewish Americans The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 Steven T. Rosenthal Seth Farber Irreconcilable Differences: The Waning of the An American Orthodox Dreamer: Rabbi American Jewish Love Affair with Israel Joseph B. -

Brenda Wawok Kinsella Horton Wildfang Family Tree

Brenda Wawok Kinsella Horton Wildfang Family Tree Ancestors of Mary Elizabeth Wiltfong, my grandmother ―The Chosen‖ We are the chosen. In each family there is one who seems called to find the ancestors. To put flesh on their bones and make them live again. To tell the family story and to feel that somehow they know and approve. Doing genealogy is not a cold gathering of facts but, instead, breathing life into all who have gone before. We are the story tellers of the tribe. All tribes have one. We have been called, as it were, by our genes. Those who have gone before cry out to us: Tell our story. So, we do. In finding them, we somehow find ourselves. How many graves have I stood before now and cried? I have lost count. How many times have I told the ancestors, "You have a wonderful family; you would be proud of us.". How many times have I walked up to a grave and felt somehow there was love there for me? I cannot say. It goes beyond just documenting facts. It goes to who I am, and why I do the things I do. It goes to seeing a cemetery about to be lost forever to weeds and indifference and saying - I can't let this happen. The bones here are bones of my bone and flesh of my flesh. It goes to doing something about it. It goes to pride in what our ancestors were able to accomplish. How they contributed to what we are today. It goes to respecting their hardships and losses, their never giving in or giving up, their resoluteness to go on and build a life for their family. -

De Nakomelingen Van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE

een genealogieonline publicatie De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE door Didi Joppe 7 augustus 2021 De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE Didi Joppe De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE Generatie 1 1. Cornelis Pieters JOPPE, is geboren 1651. Hij is getrouwd 1670 met Pieternella CORNELISSEN. Zij kregen 4 kinderen: Pieter Cornelisse JOPPE, volg 2. Cornelis Cornelisse JOPPE, volg 3. Neeltje JOPPE, volg 4. Leendert JOPPE, volg 5. Cornelis Pieters is overleden. Generatie 2 2. Pieter Cornelisse JOPPE, zoon van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE en Pieternella CORNELISSEN, is geboren 1671. Hij is getrouwd (1) 1691 met Dingetje Marinusse JAGT. Zij kregen 7 kinderen: Cornelia Pieterse JOPPE, volg 9. Marinis Pieterszn JOPPE, volg 10. Pieter Pieterse JOPPE, volg 11. Marietje Pieters JOPPE, volg 12. Cornelis Pieters JOPPE, volg 13. Rachel Pieterse JOPPE, volg 14. Tannetje Pieters JOPPE, volg 15. Hij is getrouwd (2) op 5 mei 1708 in Stavenisse,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS met Susanna Marinus TAMBOER, dochter van Marinus Jacobs TAMBOERS en Susanna Leunisdr HAGE. Zij is geboren 1665. Susanna Marinus is overleden op 1 oktober 1708 in Sint Annaland,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS. Zij kregen 1 kind: Marinus JOPPE, volg 16. Hij is getrouwd (3) op 6 December 1710 in Sint Annaland,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS met Dina Marinus GOEDEGEBEURE. Zij kregen 3 kinderen: Leendert Pieterszn JOPPE, volg 6. Isak Pieterszn JOPPE, volg 7. Pieternelletje JOPPE, volg 8. Pieter Cornelisse is overleden op 17 juni 1719 in Sint Annaland,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS. https://www.genealogieonline.nl/stamboom-joppe/ 1 De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE Didi Joppe 3. Cornelis Cornelisse JOPPE, zoon van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE en Pieternella CORNELISSEN, is gedoopt op 21 juni 1676 in Colijnsplaat,,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS. -

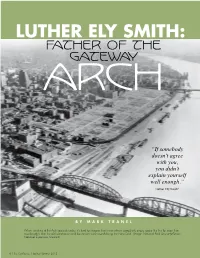

Father of the Gateway Arch | the Confluence

LUTHER ELY SMITH: Father of the Gateway Arch “If somebody doesn’t agree with you, you didn’t explain yourself well enough.” Luther Ely Smith1 BY MARK TRANEL When standing at the Arch grounds today, it’s hard to imagine that it was almost completely empty space like this for more than two decades after the old warehouses and businesses were razed during the New Deal. (Image: National Park Service-Jefferson National Expansion Museum) 6 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2012 As St. Louis pursues an initiative established a Civil Service to frame the Gateway Arch with more Commission in 1941, he was active and esthetic grounds, and with appointed to leadership roles, first as a goal of completing the project by vice-chairman until 1945 and then 2015, the legacy of Luther Ely Smith as chairman until 1950. From 1939 and his unique role in the creation to 1941, Smith was chairman of of the Jefferson National Expansion the organization committee for the Memorial (the national park Missouri non-partisan court plan, surrounding the Arch) is a reminder of which successfully led an initiative the tenacity such major civic projects petition to amend the Missouri require. What is today a national park Constitution to appoint appellate was in the mid-nineteenth century the court judges by merit rather than heart of commerce on the Missouri Trained as a lawyer, Luther Ely Smith political connections.3 He was also and Mississippi rivers; forty years (1873-1951) was at the forefront of urban president of the St. Louis City Club.4 later it was the first dilapidated urban planning. -

Rochester Sentinel 2017 January 1, 2017 Holiday-No Paper January 2, 2017 Holiday-No Paper January 3, 2017 Teresa L. Honeycutt Se

Rochester Sentinel 2017 January 1, 2017 Holiday-No Paper January 2, 2017 Holiday-No Paper January 3, 2017 Teresa L. Honeycutt Sept. 25, 1955 – Jan. 1, 2017 Teresa L. Honeycutt, 61, of rural Akron, passed away at 4:50 a.m. Sunday, Jan. 1, 2017, at her residence after being in failing health for six months. She was born on Sept. 25, 1955, in Paintsville, Ky., to Willis Roby and Ellen Arlene (Murry) Fairchild. On Sept. 23, 1972, in Paintsville, Ky., she married Billy R. Honeycutt. He survives. She worked at Comfort Inn of Rochester and Peabody Retirement Community of North Manchester and was a loving wife and mother. Teresa was a member of the House of Prayer church of Akron since 1989. She loved spending time with family and enjoyed shopping for all kinds of things. She also enjoyed country and gospel music. Survivors include her husband, Bill Honeycutt, Akron; her daughters, Lisa Honeycutt, Akron, Mandy and husband Justin Gearhart, Akron, and Tonya and husband Ryan Kirksey, Akron; six grandchildren, Dylan, Deziree, Madison, Jake, Blake and Breanna; her sisters, Paula and Sheila; and her brothers, Lee, Phillip and Mike. She was preceded in death by her parents; her daughter, Sherry; her sisters, Francis, Mag and Brenda; and her brother, Victor. Funeral service is 2 p.m. Wednesday, Jan. 4, 2017, at Hartzler Funeral Home, 305 W. Rochester St., Akron, with Pastor Danny Honeycutt officiating. Burial is at Akron Cemetery. Visitation is from 11 a.m. until the time of the service Wednesday at the funeral home. Memorial contributions may be made to Teresa’s family. -

A Programmatic Assessment of the U.S. Department of Energy Low-Income Weatherization Assistance Program

A PROGRAMMATIC ASSESSMENT OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY LOW-INCOME WEATHERIZATION ASSISTANCE PROGRAM Prepared by Shiva RaissiCharmakani A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science (Natural Resources and Environment) University of Michigan April 2018 Faculty Advisor: Tony G. Reames Table of Contents Abstract ii Dedications iii Acknowledgements iv Acronyms v Introduction 1 Background and Literature Review 7 Methodology 14 Discussion of the Results 19 Conclusions and Policy Implications 35 References 37 i ABSTRACT Performing energy efficiency measures in aging housing stock could save on energy bills especially in communities burdened by utility costs. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Weatherization Assistance Program has helped more than 7 million income-qualified households during over 40 years since its implementation in 1976, under title IV of the Energy Conservation and Production Act. The purpose of this study is to look at this program from a perspective other than benefit-cost analysis. This paper is based on analyzing the interviews conducted with leaders, supervisors, and chairpersons at four local Community Action Agencies (CAAs) in Southeast Michigan. It examines the barriers in implementing the program as well the opportunities to assist CAAs with those barriers. It also discusses the positive impacts of the program and the consequences of potential budget cuts. Currently, lack of sufficient federal funding, high number of application deferrals known as “walk-aways”, -

2018 Fact Sheets

GATEWAY ARCH A Symbol of Westward Expansion for More Than 50 Years America’s tallest man-made monument at 630 feet, the Gateway Arch has beckoned visitors for more than 50 years with its iconic, awe-inspiring shape. The vision of renowned architect Eero Saarinen, the Arch commemorates Thomas Jefferson and St. Louis’ role in the westward expansion of the United States. Along with the Old Courthouse, it makes up the 90.96-acre Gateway Arch National Park (formerly Jefferson National Expansion Memorial). The CityArchRiver project, a $380-million plan to enhance the Arch visitor experience, is nearly complete. Visitors can now enjoy 11 new acres of parkland and over five miles of bike and walking paths, as well as the North Gateway, an outdoor natural amphitheater for events and performances. The redesigned Luther Ely Smith Square located between the Gateway Arch and Old Courthouse boasts an expanded park that stretches over the highway, leading to the Gateway Arch’s new west-facing entrance connecting the Arch directly to downtown St. Louis for the first time. The Museum at the Gateway Arch will celebrate its grand opening on July 3, 2018. Visitors to the Arch can enjoy the Tram Ride to the Top; watch the award- winning documentary Monument to the Dream, which details the Arch’s construction; take part in National Park Service interactive educational programs; and shop for memorabilia, gifts and even homemade fudge at The Arch Store, located in the Arch Visitor Center. Private events at the Gateway Arch will be available once again beginning Fall 2018. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Major Jethro (Jesse) Yates 1 Major Jethro (Jesse) Yates 1776 - 1851 d: 27 Oct 1851 in Nails Creek, Dickson County, Tennessee b: Abt. Aug 1776 in Wake Co, North Carolina .... +Nancy Harwood - 1843 d: Abt. 1843 in Dickson (Piney), Tennessee b: in Wake Co, North Carolina ........ 2 Rosanah (Rosey) Yates 1801 - d: in Humphreys County Tennessee b: 1801 in Wake County, North Carolina .............. +O'Kelley McGhee 1798 - d: in Humphreys County Tennessee b: 1798 in Wake County, North Carolina ................... 3 Henry McGhee 1834 - b: 1834 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 William McGhee 1837 - b: 1837 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 Frances McGhee 1838 - b: 1838 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 John McGhee 1841 - b: 1841 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 Dilly McGhee 1842 - b: 1842 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 James Vernon McGhee 1843 - b: 1843 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 Joshua McGhee 1847 - b: 1847 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ................... 3 Kidrey McGhee 1850 - b: 10 May 1850 in Humphreys County, Tennessee ........ 2 John Yates 1804 - 1884 d: Abt. 1884 in Water Valley, Kentucky b: 1804 in Wake County, North Carolina .............. +Addeline Cumby 1807 - 1890 d: Abt. 1890 in Dickson, Dickson County, Tennessee b: 1807 in Virginia ................... 3 Margaret (Maggie) Yates 1825 - d: in Hickman County, Tennessee b: 1825 in Limestone County, Alabama ......................... +William B. (Baldy Bill) Dunnagan 1821 - d: in Hickman County, Tennessee b: 02 Sep 1821 in Hickman County, Tennessee ............................. 4 Dizie Adeline Dunnagan 1851 - 1894 d: Apr 1894 in Dickson County, Tennessee b: 28 Dec 1851 in Hickman County, Tennessee ................................... +James McFarland (Mac) Davidson 1846 - b: 25 Dec 1846 in Dickson County, Tennessee ....................................... -

Education and Training for the World of Work, a Vocational Education Program for the State of Michigan

REPOR TRESUMES ED. 011926 VT 000 410 EDUCATION AND TRAINING FOR THE WORLD OF WORK, A VOCATIONAL EDUCATION PROGRAM FOR THE STATE OF MICHIGAN. BY- SMITH, HAROLD T. W. E. UPJOHN INST. FOR EMPLOYMENT RESEARCH FUS DATE JUL 63 EDRS PRICEMF-$0.27 HC-$6.56 164P. DESCRIPTORS- SECONDARY EDUCATION, *POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION, ADULT EDUCATION, VOCATIONAL EDUCATION, *TECHNICAL EDUCATION, FEDERAL LEGISLATION, SUPERVISION, FEDERAL AID, EDUCATIONAL FINANCE, COMMUNITY COLLEGES, *AREA VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS, MICHIGAN, CONNECTICUT, NEW YORK, PENNSYLVANIA, FLORIDA, OHIO, KENTUCKY, NORTH CAROLINA, CALIFORNIA, ILLINOIS, MINNESOTA, RECOMMENDATIONS ARE PRESENTED FORDEVELOPING A MATURE SYSTEM OF VOCATIONAL AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION IN MICHIGAN.,THE NEEDS OF EDUCATION ARE PRESENTED. SECONDARY I.NSTITUTIPNS4 POSTSECONDARY PROGRAMS, FINANCING, STATE SUPERVISION, TEACHERS, RESEARCH, AND COUNSELING ARE DISCUSSED. THE HUB OF THE VOCATIONAL EDUCATION SYSTEM OF TOMORROW WILL BE THE COMPREHENSIVE AREA POSTSECONDARY AND ADULT EDUCATION INSTITUTION WHICH SHOULD BE IN EVERY COMMUNITY IN THE STATE. WHEN AN AREA IS NOT ABLE TO SUPPORT A POSTSECONDARY INSTITUTION, A COOPERATIVE AREA VOCATIONAL FACILITY OR EDUCATION CENTER SHOULD BE ESTABLISHED WITHIN A COMMUTING AREA AS AN EMBRYO POSTSECONDARY AND ADULT EDUCATION. INSTITUTION. REPORTS ON WHAT IS BEING DONE OR CONSIDERED IN VOCATIONAL EDUCATION ARE GIVEN FOR SUCH SELECTED AREAS AS CALIFORNIA, CONNECTICUT, FLORIDA, KENTUCKY, ILLINOIS, MICHIGAN, MINNESOTA, NEW YORK, NORTH CAROLINA, OHIO, AND PENNSYLVANIA. INCLUDED IN THE APPENDIX IS "EXAMPLE OF ABASIC CLASSROOM UNIT FOUNDATION FORMULA FOR DETERMINING STATE SUPPORT OF ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION IN A HYPOTHETICAL STATE." THIS DOCUMENT IS ALSO AVAILABLE FROMTHE W.E. UPJOHN INSTITUTE FOR EMPLOYMENT RESEARCH,7(39 SOUTH WESTNEDGE AVENUE, KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN 49250. (SL) Education and Training for the World ofWork A Vocational Education Program for the State of Michigan By Harold T. -

Marshaling Citizen Power

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. MARSHALING CITIZEN POWER . TO .. MODERNIZE . , ',. : \,I ! t! 'I: . THE PRESIDENTIAL CALL FOR ACTION TO MODERNIZE CORRECTIONS "At long last, this nation is coming to realize that the process of justice can,lot end with the slam ming shut of prison gates. "Ninety-eight out of every hundred criminals who are sent to prison come back out into society. t' That means that American concerned with every l stopping crime must ask this question: Are we " doing all we can to make certain that many more I men and women who come out of prison will become law abiding citizens? "The answer to that question today, after centuries r of neglect, is no. We have made important strides in the past two years, but let us not deceive our I selves: Our prisons are still colleges of crime, and not what they should be-the beginning of a way f back to a productive life within the law. "To turn back the wave of crime, we must have more effective police work, and we must have I court reform to ensure trials that are speedy and I fair. But let us also remember that the protection of society depends largely on the correction of the crimiral." President Richard M. Nixon First National Conference nn Corrections December 6, 1971 Order from: Chamber of Commerce of the United States 1615 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 (The foHowing includes mailing and handling) 1.9 copies .................... oc ......... 51.00 each 9.100. -

Gateway National Park's Arch Is America's Tallest Monument. It Reaches a Height of 630 Feet (63 Stories Hi

Gateway National Park’s arch is America’s tallest monument. It reaches a height of 630 feet (63 stories high) above the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri. It is an engineering marvel. The St. Louis landmark had its beginning in 1933, when local business leaders wanted to enhance the city’s waterfront, which had suffered an economic downturn and dilapidation. The group’s vision was to revise the waterfront area and place a landmark there which would become known as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. It would celebrate President Thomas Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1935, an association, with the same name, was created to work on that vision. A political fiasco took place during the ensuing years. It caused a tearing down of a 40‐block area of the city, which contained 290 businesses. In 1940, St. Louis rivaled New York City; it was then the 8th largest city in the United States. The city of St. Louis covers a 62 square mile area. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of July 2016, it ranks 61st. Crime, poverty, racial tensions and an inability to infuse new business have been some of the criticisms for its drop in population and stature. However, the erection of the monument‐ arch has made it a national landmark. The monument‐arch became a reality when Eero Saarinen won a nationwide competition from 172 submissions in 1947, but delays took place. On June 23, 1959, a ground‐breaking ceremony took place, however construction didn’t begin until February 1963.