Prevention Program Management. Participant Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generation One 1. Reuben Burlingham #116989. He Married

Family of Reuben Burlingham compiled by John A. Brebner for the Friends of Sandbanks 26th October, 2020 Generation One 1. Reuben Burlingham #116989. He married Elizabeth (unidentfied) #116990. Children: 2. i. Reuben Burlingham #73590 b. 27 March 1784. 3. ii. Varnum Burlingham #82688 b. c. 1793. Generation Two 2. Reuben Burlingham #73590, b. 27 March 1784 in New York State, United States,1,2,3 occupation 1851 Farmer, religion Society of Friends/Quakers, d. 27 April 1857 in Prince Edward County, Ontario,1,4 buried in Bloomfield Friends' Cemetery, Hallowell Township, Prince Edward County, Ontario.5 . 1851: Lived in Blenheim (Hallowell Township), Prince Edward County with family. He married Phoebe Leavens #73591, 09 September 1805 in Hallowell Township, Prince Edward County, Ontario,6 b. 04/05 February 1791 in Nine Partners, Dutchess County, New York State,1,2,6 (daughter of Benjamin Leavens #70964 [Shoemaker and Farmer] and Sarah Cunningham #70965), d. 16 January 1881 in Bloomfield, Hallowell Township, Prince Edward County,1,7 buried in Bloomfield Friends' Cemetery, Hallowell Township, Prince Edward County, Ontario.5 Phoebe: 1871: Was she living with son David and wife Jane in Hallowell Township? Or was that Phoebe BULL? Children: 4. i. Catherine Burlingham #74245 b. 02 February 1807. 5. ii. Caroline Burlingham #74620 b. 1808. 6. iii. Daniel Leavens Burlingham #74486 b. 1810. 7. iv. Mary (Polly) Burlingham #70888 b. 14 May 1813. 8. v. Benjamin Leavens Burlingham #73596 b. 02 October 1816. 9. vi. David Burlingham #73597 b. 1818. 1 10. vii. Jonathan Burlingham #69589 b. 1816 - 1818. 11. viii. Cornelius Burlingham #73598 b. -

Descendants of William Hayward 20 May 2018

Descendants of William Hayward 20 May 2018 First Generation 1. William HAYWARD was born in 1550 in England,. Ancestral File Number: WWTL-V8. William HAYWARD had the following child: 2 i. John William HAYWARD, born 1583, England, London. Second Generation 2. John William HAYWARD (William-1) was born in 1583 in England, London. Ancestral File Number: V6JH-2C. Mrs. John William HAYWARD was born in 1589 in England, Middlesex, London. Ancestral File Number: V6JH-3J. John William HAYWARD and John William HAYWARD had the following child: 3 i. William HAYWARD, born 6 Feb 1617, England, Middlesex, London; died 10 May 1659, Massachusetts, Norfolk, Braintree. Third Generation 3. William HAYWARD (John William-2, William-1) was born on 6 Feb 1617 in England, Middlesex, London. He died on 10 May 1659 at the age of 42 in Massachusetts, Norfolk, Braintree. Ancestral File Number: 4JG8-BH. Margery KNIGHT was born in 1621 in England, Gloucaster, Thornbury. Ancestral File Number: 4JG8-CN. William HAYWARD and Margery KNIGHT had the following children: 4 i. Huldah HAYWARD, born 7 Oct 1636, England, Middlesex, London; married Ferdinando THAYER, 14 Jan 1652, Massachusetts, Norfolk, Braintree; died 1 Sep 1690, Massachusetts, Norfolk, Mendon. ii. Jonathan HAYWARD was born in 1641. He died on 21 Nov 1690 at the age of 49 in Massachusetts, Norfolk, Braintree. AFN: 4JGB-8F. 5 iii. Samuel HAYWARD, born 4 Jan 1642; died 20 Jul 1713, Massachusetts, Norfolk, Mendon. 6 iv. William HAYWARD, born 1647, Massachusetts, Norfolk, Braintree; died 17 Dec 1718, Massachusetts, Norfolk, Braintree. Fourth Generation 4. Huldah HAYWARD (William-3, John William-2, William-1) was born on 7 Oct 1636 in England, Middlesex, London. -

Monument to a to a Dream

Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle Monument 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~37 1 Manifest Destiny 38~63 2 The Spirit of St. Louis To A 64~134 3 On the Riverfront 135~229 4 The Competition 230~293 5 Wunderkind Dream 294~391 6 Post-Competition Blues 392~478 7 Two Weaknesses 479~536 8 Topsy-Turvy 537~582 9 Peripheral Development 583~600 10 Legacy 1 2 Part 1 Corps of Discovery Manifest Destiny 3 4 Thomas Jefferson had a long interest in western expansion and in 1780s met John Ledyard who discussed with him an expedition to the Pacific Northwest. Two years into his presidency, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition through the Louisiana Purchase and beyond; to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition’s goals were: • Explore the Louisiana Purchase; • Establish trade and U.S. sovereignty over the native peoples along the Missouri River; “To find the most direct & • Establish a U.S. claim of “Discovery” to the Pacific Northwest and practicable water communication Oregon Territory by documenting an American presence there before across this continent, for the Europeans could claim the land; purposes of commerce.” • Seek out a “Northwest Passage” Thomas Jefferson,POTUS Jefferson also understood the U.S. would have a better claim of RE: the Lewis and Clark Expedition, ownership to the Pacific Northwest if the expedition gathered scientific a.k.a. the Corps of Discovery data on indigenous animals and plants. The U.S. mint prepared special Expedition (1804–1806). It was the first silver medals (with a portrait of Jefferson) which had a message of transcontinental expedition to the friendship and peace, called Indian Peace Medals or Peace Medals.The Pacific coast undertaken by the United Corps was entrusted to distribute them to the Indian nations they met States. -

Excursions 6 Day Cruise "Rhine-Mosselle-Romance"

Excursions 6 Day Cruise "Rhine-Mosselle-Romance" 2nd Day: City Tour of Koblenz with the fortress “Ehrenbreitstein” / 39 € per person The trip starts with a tour of the imperial city in the "German corner". Koblenz is one of the oldest cities in Germany. The trip takes you past the historic town hall with the “Schängelbrunnen” (fountain) and many other interesting points of the city. For example you will see the “Coin Master House“called “Alte Münze“(old coin) which is located on “Münzplatz”(coin square). At this location is the birthplace of Prince Metternich too. Also, worth seeing is the “Balduinbrücke”, the second oldest, still maintaining bridge that crosses the river Moselle. The bridge dates from the 14th century. Then it goes up with the cabin cable car - to the “Ehrenbreitstein” fortress, which is situated on a 118-m high mountain spur. The inclined lift (opened in 2011) in the District of “Ehrenbreitstein” connects the Mill Valley with the East side of the fortress. Be mesmerized by a breath taking panoramic view of the city. 2nd Day: Excursion “Castle Sayn and garden of butterflies” / 49 € per person This excursion will bring you by bus from the pier to the castle Sayn. During a guided tour through the royal rooms you will be able to imagine how life was for the family Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn. The Great Salon, which is still available for weddings and other gatherings, is lined with portraits of Prince Ludwig and Princess Leonilla. The Russian salon you are able to see a bust of Princess Charlotte of Prussia. -

Claims Resolution Tribunal

CLAIMS RESOLUTION TRIBUNAL In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation Case No. CV96-4849 Certified Award to Claimant [REDACTED 1] also acting on behalf of [REDACTED 2], [REDACTED 3], and [REDACTED 4], to Claimant [REDACTED 5], to Claimant [REDACTED 6], to Claimant [REDACTED 7], to Claimant [REDACTED 8], to Claimant [REDACTED 9], to Claimant [REDACTED 10], to Claimant [REDACTED 11], represented by Erez Bernstein and to Claimant [REDACTED 12] in re Account of Lina Czerny Claim Numbers: 219538/HS, 222548/HS, 501235/HS, 501249/HS, 501370/HS, 501529/HS, 501564/HS, 501813/HS, 790482/HS1 Award Amount: 26,750.00 Swiss Francs This Certified Award is based upon the claim of [REDACTED 1] ( Claimant [REDACTED 1] ) to the published account of Icek Goldstein; the claim of [REDACTED 5] ( Claimant [REDACTED 5] ) to the published accounts of Lina Czerny and Dawid Czerny; the claims of 1 Claimant [REDACTED 12] ( Claimant [REDACTED 12] ) did not submit a CRT Claim Form. However, in 1997 he submitted an ATAG Ernst & Young claim form ( ATAG Form ), numbered C-BUD-D-50-198-134-059, to the Claims Resolution Tribunal for Dormant Accounts in Switzerland ( CRT I ), which arbitrated claims to certain dormant Swiss bank accounts between 1997 and 2001. On 30 December 2004, the Court ordered that claims submitted to but not treated by either CRT I, the Independent Committee of Eminent Persons ( ICEP ), or ATAG Ernst & Young shall be treated as timely claims under the current Claims Resolution Process (the CRT ) as defined in the Rules Governing the Claims Resolution Process, as amended (the Rules ). -

Freiburg, 31.05.2020 Umsetzung Der EG-Wasserrahmenrichtlinie in Ba.-Wü. Dritte Bewirtschaftungsperiode 2021 Bis 2027 „Vorgezo

regioWasser e.V. – Freiburger Arbeitskreis Wasser im Bundesverband Bürgerinitiativen Umweltschutz e.V. (BBU) Mitglied im Klimaschutzbündnis Freiburg Grete-Borgmann-Straße 10 79106 Freiburg Tel.: 0761/275693, 4568 7153 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.akwasser.de Freiburg, 31.05.2020 Umsetzung der EG-Wasserrahmenrichtlinie in Ba.-Wü. Dritte Bewirtschaftungsperiode 2021 bis 2027 „Vorgezogene Öffentlichkeitsbeteiligung“ INKA-Eintragungen Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebes WRRL-Team, zunächst ein großes Dankesschön für die viele Arbeit, die in der digitalen Öffentlich- keitsbeteiligung steckt! Bei unseren Kontakten in die anderen Bundesländer heben wir bei jeder Gelegenheit die traditionelle Vorbildfunktion von Ba.-Wü. bei der „vorge- zogenen Öffentlichkeitsbeteiligung“ hervor. Für unseren großen Themenkatalog eignet sich jedoch das INKA-System nur be- grenzt. Deshalb greifen wir die von Ihnen genannte Möglichkeit auf, Ihnen zunächst unsere allgemeinen Vorschläge und ganz untenstehend die speziellen Maßnahmen- vorschläge zur Rench, zur Kinzig, zur Elz und zu einigen der Hochrheingewässer via E-Mail zukommen zu lassen. (Bei der Vielzahl unserer Anmerkungen und Hinweise geht es als Fließtext deutlich einfacher und schneller, als wenn wir über INKA jeden betreffenden Maßnahmenpunkt anklicken und das Hinweisfenster öffnen müssten.) Warum scheitert die Umsetzung der EG-Wasserrahmenrichtlinie? Nachdem in den ersten beiden Bewirtschaftungszyklen „die tiefhängenden Früchte“ abgeerntet worden sind, haben wir jetzt zu Beginn der dritten Bewirtschaftungsperio- -

GIA Reader, Volume 31, Number 3 (Winter 2021)

Vol. 31 No. 3, Fall 2020/Winter 2021 A Journal on Arts Philanthropy 2 Grantmakers in the Arts Reader: Volume 31, No. 3, Fall 2020/Winter 2021 RESEARCH Foundation Grants to Arts and Culture, 2018: A One-Year Snapshot ...................................................5 Reina Mukai Public Funding for the Arts 2020 ............................................................................................................12 Ryan Stubbs and Patricia Mullaney-Loss READINGS Centered. Elevated. Celebrated. Well Resourced. Welcome to Nonprofit Wakanda. .........................16 David McGoy DEI Work is Governance Work ................................................................................................................18 Jim Canales and Barbara Hostetter The Equity Builder Loan Program: Looking Toward Autonomy and Freedom from the Crisis Cycle ................................................................................................................................20 Quinton Skinner Equity. Equity. Equity. ..............................................................................................................................25 Shaunda McDill Arts Funders Should Build Stability and Resilience for Black Artists and Cultural Communities .......................................................................................................................26 Tracey Knuckles A Question of (dis)Trust: Lessons When Your Institution Gets Taken Down ....................................27 Anida Yoeu Ali and Shin Yu Pai San Diego/Tijuana: -

Lloyd E. Rigler

Lloyd E. Rigler Send Flowers loyd Eugene Rigler, a California industrialist and investor whose arts philanthropy ranged from L music in Los Angeles to ballet in his native Northern Plains to the New York City Opera to public television, died Dec. 7 at his home in Los Angeles. He was 88. His death was announced by the Rigler-Deutsch Foundation in Hollywood, of which he was president, and the New York City Opera, of which he was vice chairman. Mr. Rigler was the founder of Classic Arts Showcase, an eclectic television service that distributes performing arts lms at no cost to public television stations, and of the American Association for Single People, which ghts for the economic rights of the unmarried. Mr. Rigler, who built a fortune with Adolph ' s Meat Tenderizer as its foundation, started as a salesman during the Depression. His connection with television also started early, with the 1939-40 New York World ' s Fair, at which he demonstrated RCA ' s new television technology to astonished audiences. He and a partner, Lawrence E. Deutsch, who joined him in making Adolph ' s Meat Tenderizer a national brand, began their philanthropy modestly in the early 1950s, when they formed the Lloyd E. Rigler-Lawrence E. Deutsch Foundation. The foundation was an innovative venture that helped make the matching funds concept a powerful fund-raising tool. Their foundation contributed to the creation of the Los Angeles Music Center and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. Deutsch died in 1977 and willed his holdings to the foundation. -

Fermaglich's I-Xiv-123

Fermaglich: American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares page i American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares Fermaglich: American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares page ii Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor Kirsten Fermaglich Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: “How Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Early Holocaust Consciousness and Liberal Camps as Jewish Socializing Experiences America, 1957–1965 Ori Z. Soltes Andrea Greenbaum, editor Fixing the World: Jewish American Painters Jews of South Florida in the Twentieth Century Sylvia Barack Fishman Gary P. Zola, editor Double or Nothing: Jewish Families and The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Mixed Marriages Jacob Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Jewry George M. Goodwin and Ellen Smith, David Zurawik editors The Jews of Prime Time The Jews of Rhode Island Ranen Omer-Sherman Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, Diaspora and Zionism in American Jewish editors Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, editors Jews of Brooklyn Michael E. Staub, editor The Jewish 1960s: An American Sourcebook Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, editors Judah M. Cohen Women and American Judaism: Historical Through the Sands of Time: A History of Perspectives the Jewish Community of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands Annelise Orleck, with photographs by Elizabeth Cooke Naomi W. Cohen The Soviet Jewish Americans The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 Steven T. Rosenthal Seth Farber Irreconcilable Differences: The Waning of the An American Orthodox Dreamer: Rabbi American Jewish Love Affair with Israel Joseph B. -

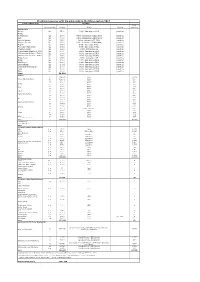

Stocking Measures with Big Salmonids in the Rhine System 2017

Stocking measures with big salmonids in the Rhine system 2017 Country/Water body Stocking smolt Kind and stage Number Origin Marking equivalent Switzerland Wiese Lp 3500 Petite Camargue B1K3 genetics Rhine Riehenteich Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue K1K2K4K4a genetics Birs Lp 4.000 Petite Camargue K1K2K4K4a genetics Arisdörferbach Lp 1.500 Petite Camargue F1 Wild genetics Hintere Frenke Lp 2.500 Petite Camargue K1K2K4K4a genetics Ergolz Lp 3.500 Petite Camargue K7C1 genetics Fluebach Harbotswil Lp 1.300 Petite Camargue K7C1 genetics Magdenerbach Lp 3.900 Petite Camargue K5 genetics Möhlinbach (Bachtele, Möhlin) Lp 600 Petite Camargue B7B8 genetics Möhlinbach (Möhlin / Zeiningen) Lp 2.000 Petite Camargue B7B8 genetics Möhlinbach (Zuzgen, Hellikon) Lp 3.500 Petite Camargue B7B8 genetics Etzgerbach Lp 4.500 Petite Camargue K5 genetics Rhine Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Old Rhine Lp 2.500 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Bachtalbach Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Inland canal Klingnau Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Surb Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Bünz Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Sum 39.300 France L0 269.147 Allier 13457 Rhein (Alt-/Restrhein) L0 142.000 Rhine 7100 La 31.500 Rhine 3150 L0 5.000 Rhine 250 Doller La 21.900 Rhine 2190 L0 2.500 Rhine 125 Thur La 12.000 Rhine 1200 L0 2.500 Rhine 125 Lauch La 5.000 Rhine 500 Fecht und Zuflüsse L0 10.000 Rhine 500 La 39.000 Rhine 3900 L0 4.200 Rhine 210 Ill La 17.500 Rhine 1750 Giessen und Zuflüsse L0 10.000 Rhine 500 La 28.472 Rhine 2847 L0 10.500 Rhine 525 -

Brenda Wawok Kinsella Horton Wildfang Family Tree

Brenda Wawok Kinsella Horton Wildfang Family Tree Ancestors of Mary Elizabeth Wiltfong, my grandmother ―The Chosen‖ We are the chosen. In each family there is one who seems called to find the ancestors. To put flesh on their bones and make them live again. To tell the family story and to feel that somehow they know and approve. Doing genealogy is not a cold gathering of facts but, instead, breathing life into all who have gone before. We are the story tellers of the tribe. All tribes have one. We have been called, as it were, by our genes. Those who have gone before cry out to us: Tell our story. So, we do. In finding them, we somehow find ourselves. How many graves have I stood before now and cried? I have lost count. How many times have I told the ancestors, "You have a wonderful family; you would be proud of us.". How many times have I walked up to a grave and felt somehow there was love there for me? I cannot say. It goes beyond just documenting facts. It goes to who I am, and why I do the things I do. It goes to seeing a cemetery about to be lost forever to weeds and indifference and saying - I can't let this happen. The bones here are bones of my bone and flesh of my flesh. It goes to doing something about it. It goes to pride in what our ancestors were able to accomplish. How they contributed to what we are today. It goes to respecting their hardships and losses, their never giving in or giving up, their resoluteness to go on and build a life for their family. -

De Nakomelingen Van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE

een genealogieonline publicatie De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE door Didi Joppe 7 augustus 2021 De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE Didi Joppe De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE Generatie 1 1. Cornelis Pieters JOPPE, is geboren 1651. Hij is getrouwd 1670 met Pieternella CORNELISSEN. Zij kregen 4 kinderen: Pieter Cornelisse JOPPE, volg 2. Cornelis Cornelisse JOPPE, volg 3. Neeltje JOPPE, volg 4. Leendert JOPPE, volg 5. Cornelis Pieters is overleden. Generatie 2 2. Pieter Cornelisse JOPPE, zoon van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE en Pieternella CORNELISSEN, is geboren 1671. Hij is getrouwd (1) 1691 met Dingetje Marinusse JAGT. Zij kregen 7 kinderen: Cornelia Pieterse JOPPE, volg 9. Marinis Pieterszn JOPPE, volg 10. Pieter Pieterse JOPPE, volg 11. Marietje Pieters JOPPE, volg 12. Cornelis Pieters JOPPE, volg 13. Rachel Pieterse JOPPE, volg 14. Tannetje Pieters JOPPE, volg 15. Hij is getrouwd (2) op 5 mei 1708 in Stavenisse,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS met Susanna Marinus TAMBOER, dochter van Marinus Jacobs TAMBOERS en Susanna Leunisdr HAGE. Zij is geboren 1665. Susanna Marinus is overleden op 1 oktober 1708 in Sint Annaland,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS. Zij kregen 1 kind: Marinus JOPPE, volg 16. Hij is getrouwd (3) op 6 December 1710 in Sint Annaland,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS met Dina Marinus GOEDEGEBEURE. Zij kregen 3 kinderen: Leendert Pieterszn JOPPE, volg 6. Isak Pieterszn JOPPE, volg 7. Pieternelletje JOPPE, volg 8. Pieter Cornelisse is overleden op 17 juni 1719 in Sint Annaland,Gemeente Tholen,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS. https://www.genealogieonline.nl/stamboom-joppe/ 1 De nakomelingen van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE Didi Joppe 3. Cornelis Cornelisse JOPPE, zoon van Cornelis Pieters JOPPE en Pieternella CORNELISSEN, is gedoopt op 21 juni 1676 in Colijnsplaat,,ZEELAND,NETHERLANDS.