The Metropolitan Project: Leadership, Policy, and Development in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y: Lawrence Halprin and Harland Barholomew's Master Plans for Charlottesville, VA, 1956-1976

Designing Identity: Lawrence Halprin and Harland Barholomew's Master Plans for Charlottesville, VA, 1956-1976 Sarita M. Herman B.A., Hollins University, 2008 School of Architecture University of Virginia May 2010 Thesis Corn,, ittee: y��Richard Guy Wilson, Director Daniel Bluestone u _u� ,.t ,� { ElizabethJeyer 0 Table of Contents List of Illustrations .................................................................................................................... , Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................. ,v Introduction................................................ .................................................................... ..1 Chapter I· History of City Planning in Charlottesv,lle ........................................................ 8 Chapter II: Harland Bartholomew, Urban Renewal, and the First Mall Plan .............. 16 Chapter Ill: Lawrence Halprin Associates and the Downtown Mall........................ 42 Chapter IV: The Legacy of Planning and Preservation in Charlottesville •........•........... 70 Bibliography.......................................... .. .......... ................................................................ 76 Illustrations .... ................................... .................................................................. ............ 83 Illustrations: 1 Map of Charlottesville, VA. Orange Star indicate ocatIon of Charlottesville in Virg nia. Detail of the central business district. Topographical -

Monument to a to a Dream

Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle Monument 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~37 1 Manifest Destiny 38~63 2 The Spirit of St. Louis To A 64~134 3 On the Riverfront 135~229 4 The Competition 230~293 5 Wunderkind Dream 294~391 6 Post-Competition Blues 392~478 7 Two Weaknesses 479~536 8 Topsy-Turvy 537~582 9 Peripheral Development 583~600 10 Legacy 1 2 Part 1 Corps of Discovery Manifest Destiny 3 4 Thomas Jefferson had a long interest in western expansion and in 1780s met John Ledyard who discussed with him an expedition to the Pacific Northwest. Two years into his presidency, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition through the Louisiana Purchase and beyond; to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition’s goals were: • Explore the Louisiana Purchase; • Establish trade and U.S. sovereignty over the native peoples along the Missouri River; “To find the most direct & • Establish a U.S. claim of “Discovery” to the Pacific Northwest and practicable water communication Oregon Territory by documenting an American presence there before across this continent, for the Europeans could claim the land; purposes of commerce.” • Seek out a “Northwest Passage” Thomas Jefferson,POTUS Jefferson also understood the U.S. would have a better claim of RE: the Lewis and Clark Expedition, ownership to the Pacific Northwest if the expedition gathered scientific a.k.a. the Corps of Discovery data on indigenous animals and plants. The U.S. mint prepared special Expedition (1804–1806). It was the first silver medals (with a portrait of Jefferson) which had a message of transcontinental expedition to the friendship and peace, called Indian Peace Medals or Peace Medals.The Pacific coast undertaken by the United Corps was entrusted to distribute them to the Indian nations they met States. -

William Jennings Bryan and His Opposition to American Imperialism in the Commoner

The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner by Dante Joseph Basista Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2019 The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner Dante Joseph Basista I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Dante Basista, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Donna DeBlasio, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT This is a study of the correspondence and published writings of three-time Democratic Presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan in relation to his role in the anti-imperialist movement that opposed the US acquisition of the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War. Historians have disagreed over whether Bryan was genuine in his opposition to an American empire in the 1900 presidential election and have overlooked the period following the election in which Bryan’s editorials opposing imperialism were a major part of his weekly newspaper, The Commoner. The argument is made that Bryan was authentic in his opposition to imperialism in the 1900 presidential election, as proven by his attention to the issue in the two years following his election loss. -

EX ALDERMAN NEWSLETTER 137 and UNAPPROVED Chesterfield 82 by John Hofmann July 26, 2014

EX ALDERMAN NEWSLETTER 137 and UNAPPROVED Chesterfield 82 By John Hofmann July 26, 2014 THIS YEAR'S DRIVING WHILE BLACK STATS: For some reason the Post-Dispatch did not decide to do a huge article on the Missouri Attorney General's release of Vehicle Traffic Stop statistical data dealing with the race of drivers stopped by police. The stats did not change that much from last year. Perhaps the Post-dispatch is tired of doing the same story over and over or finally realized that the statistics paint an unfair picture because the overall region's racial breakdown is not used in areas with large interstate highways bringing hundreds of thousands of people into mostly white communities. This does not mean profiling and racism doesn't exist, but is not as widespread as it was 30 years ago. Traffic stop statistics for cities are based on their local populations and not on regional populations. This can be blatantly unfair when there are large shopping districts that draw people from all over a region or Interstate highways that bring people from all over the region through a community. CHESTERFIELD: Once again the Chesterfield Police come off looking pretty good. The four largest racial groups in Chesterfield are: Whites (84%) Asians (9%), Hispanics (2.9%) and Blacks (2.6%). If you believe in these statistics they show the Chesterfield Police are stopping too many whites and blacks and not stopping enough Asians and Hispanics. That is what is wrong with the Missouri Collection of Traffic data. The County wide population data comes into play since there is a major Interstate Highway going through Chesterfield and four major shopping districts. -

Current, October 30, 1980

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (1980s) Student Newspapers 10-30-1980 Current, October 30, 1980 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current1980s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, October 30, 1980" (1980). Current (1980s). 25. https://irl.umsl.edu/current1980s/25 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (1980s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CXT08ER 30 1980 ISSUE 382 UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI j'SAINT LOU1S Architects meet; plans finalized Volsko said. "The menu will be B~b DePalma subject to change at any time according to my discretion and A group of UMSL representa to the interests of customers." tives met with Hageman Inte The sweet shop will include a riors Inc. and W . Milt Santee variety of pies, cakes and cook Oct. 23 and 24 to draw up plans ies that will be baked in the for the renovation of the cafete cafeteria kitchen. Ice cream and ria and snack bar. shakes will also be sold. The group was headed by In the middle of the shopping John Perry, vice chancellor of area will be a soup and salad Administrative Services. Other bar along with a beverage island members included Bill Edwards, for coffee and sodas. University Center director, Another major change in the Charlotte McClure, University cafeteria will be an increase in Center assistant director, Greg the amount of people it will seat. -

Gerald R. Ford Administration White House Press Releases

-. Digitized from Box 33 of the White House Press Releases at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library- FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OCTOBER 29, 1976 OFFICE OF THE WHITE HOUSE PRESS SECRETARY (St. Louis, Missouri) THE WHITE HOUSE REMARKS OF THE PRESIDENT AT THE LUTHER ELY SMITH MEMORIAL PARK 12 : 2 7 P . M. CDT Thank you very, very much Jack Danforth. May I say at this point, nothing would make me happier than to have Jack Danforth as your next United States Senator. You need Jack Danforth, and I need him, so let's go work and make sure he is elected November 2. It is great to be back in Missouri, to have the opportunity of being in a State so wonderfully han1led~ by your fine, fine Governor, Kit Bond, and hi~ very, very able Lieutenant Governor, Bill Phelps. I am indebted, of course, to your good f:.:"iend and mine, Gene McNary. Gene, thank you. But there are two wonderful people here who have made extraordinary efforts. Peter Graves has been your master of ceremonies. Peter, thank you very, very much; and one of my all-time favorites, Al Hirt. Al, thank you. A very dear friend of mine and a great person who was born and brought up right here in St. Louis has been traveling with me for the last ten days. Unfortunately, he had a prior commitment that prevented him from coming here to St. Louis. But, I have gotten to know I think one of the most fabulous people in this whole country. Do any of you remember the name of Joe Garagiola? Joe has taken about ten days of his time and is out campaigning on behalf of Jerry Ford and Bob Dole. -

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition BY JENNIFER CLARK The seven-person jury seated around a table in the Old Courthouse with competition advisor George Howe in 1947. The jury met twice to assess designs and decide what the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial would look like. The designs included far more than a memorial structure. A landscaped 90-acre park, various structures, water features, a campfire theater, museum buildings, and restaurants were also part of the designs. (Image: National Park Service, Gateway Arch National Park) 8 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2018 Today it is hard to conceive of any monument Saint Louis Art Museum; Roland A. Wank, the chief that could represent so perfectly St. Louis’ role architect of the Tennessee Valley Authority; William in westward expansion as the Gateway Arch. The W. Wurster, dean of architecture at MIT; and Richard city’s skyline is so defined by the Arch that it J. Neutra, a well-known modernist architect. George seems impossible that any other monument could Howe was present for the jury’s deliberations and stand there. However, when the Jefferson National made comments, but he had no vote. Expansion Memorial (JNEM) was created by LaBeaume created a detailed booklet for the executive order in 1935, no one knew what form competition to illustrate the many driving forces the memorial would take. In 1947, an architectural behind the memorial and the different needs it was competition was held, financed by the Jefferson intended to fulfill. Concerns included adequate National Expansion Memorial Association, parking, the ability of the National Park Service a nonprofit agency responsible for the early to preserve the area as a historic site, and the development of the memorial idea. -

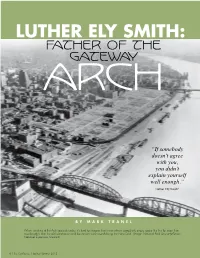

Father of the Gateway Arch | the Confluence

LUTHER ELY SMITH: Father of the Gateway Arch “If somebody doesn’t agree with you, you didn’t explain yourself well enough.” Luther Ely Smith1 BY MARK TRANEL When standing at the Arch grounds today, it’s hard to imagine that it was almost completely empty space like this for more than two decades after the old warehouses and businesses were razed during the New Deal. (Image: National Park Service-Jefferson National Expansion Museum) 6 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2012 As St. Louis pursues an initiative established a Civil Service to frame the Gateway Arch with more Commission in 1941, he was active and esthetic grounds, and with appointed to leadership roles, first as a goal of completing the project by vice-chairman until 1945 and then 2015, the legacy of Luther Ely Smith as chairman until 1950. From 1939 and his unique role in the creation to 1941, Smith was chairman of of the Jefferson National Expansion the organization committee for the Memorial (the national park Missouri non-partisan court plan, surrounding the Arch) is a reminder of which successfully led an initiative the tenacity such major civic projects petition to amend the Missouri require. What is today a national park Constitution to appoint appellate was in the mid-nineteenth century the court judges by merit rather than heart of commerce on the Missouri Trained as a lawyer, Luther Ely Smith political connections.3 He was also and Mississippi rivers; forty years (1873-1951) was at the forefront of urban president of the St. Louis City Club.4 later it was the first dilapidated urban planning. -

Forsite195153univ.Pdf

710-5 FO 1351-53 The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library SEP -4 JUL 1 5 m JUL J S FEB 2 9 /:> NOV 1 O L L161— O-1096 kaw 951 THE LIBRARY Ot THE UNIVERSITY OE ILLINOIS forsite STAFF FORSITE ! 5I nancy seith editor jerry harper assistant editor bob giltner student work ralpn synnestvedt business brad taylor cover page wait keith faculty advisor student staff publishers INTRODUCTION nancy seith edi tor 1 la 5 FORSITE is the students 1 attemot to reach out into the profession and gain knowledge from a source long rec- ognized as the best — - experience With this first issue of FORSITE we hope to open a chan- nel for the exchange of ideas between the practicing members of the profession and those who are learning it. This will also be a place for the interchange of per- sonal views and current trends among practicing land- scape architects. We want to form a closer tie between the profession and education,. The student in education today will be in the profession tomorrow working with you. Will that person stepping out of education be equipped with the practical knowledge and ability necessary to adapt to the professional world? He will be if his preparatory work is geared to professional practice. We hope that this publication will oil the gears by bringing your ideas and achievements to the students while they are still news. -

Congressional Record—Senate S5613

May 24, 2001 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S5613 EC–2042. A communication from the Acting dren with disabilities when federal law au- By Mr. REED for the Committee on Armed Chief of the Marine Mammal Conservation thorizes the appropriation of up to forty per Services. Division, National Marine Fisheries Service, cent; and The following named officer for appoint- Office of Protected Resources, Department of Whereas, the Hawaii Department of Edu- ment in the Reserve of the Air Force to the Commerce, transmitting, pursuant to law, cation received approximately $23,500,000 in grade indicated under title 10, U.S.C., section the report of a rule entitled ‘‘Taking of Ma- federal funds during fiscal year 1999–2000 for 12203: rine Mammals Incidental to Commercial what was then referred to as ‘‘education of To be brigadier general Fishing Operations; Atlantic Large Whale the handicapped’’. If this figure represented Col. Fred F. Castle Jr., 0000 Take Reduction Plan Regulations’’ (RIN0648– an appropriation of funds for ten per cent of AN88) received on May 21, 2001; to the Com- special education and related services for The following named officers for appoint- mittee on Commerce, Science, and Transpor- children with disabilities, then an appropria- ment in the Reserve of the Air Force to the tation. tion of forty per cent would have equaled grade indicated under title 10, U.S.C., section EC–2043. A communication from the Acting $94,000,000; and 12203: Chief of the Marine Mammal Conservation Whereas, the difference between an appro- To be major general Division, National Marine Fisheries Service, priation of forty per cent and an appropria- Brig. -

Bartholomew (Harland) and Associates

BARTHOLOMEW (HARLAND) AND ASSOCIATES. A REPORT UPON POPULATION GROWTH AND DISTRIBUTION, CITY OF ATLANTA AMD FULTON COUNTY, GEORGIA HB 3527 -A74 B37 1953 WILLIAM RUSSELL PULLEN LIBRARY Georgia State University University System of Georgia WILLIAM RUSSELL PULLEN LIBRARY GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY MUNICIPAL PLANNING BOARD JfcriiANTAv 3j, CeoRD|A^ July 6, 1953- ( M CUBA AIRMAN R. JOUNG v E-CHAIRMAN s Asbell Mayor and General Co vine il 3ERT G. Henduey of the City of Atlanta JL I Miller J. N icholson Commissioners of Roads and NRY J. Toombs Revenues of Fulton County Gentlemen: 'ONT B. Bean PI ANNINQ ENGINEER Proceeding on the authority of an Ordinance by the Mayor and General Council of the City of Atlanta and a Resolution by the Commissioners of Roads and Revenues of Fulton County, the Municipal Planning Board, on January 16, 1953> initiated a program to prepare new land use plans, modernize the zoning laws and regulations, and to prepare a major street plan for the City of Atlanta and Fulton County. Ihe Municipal Planning Board and its consultants have been studying population trends and factors influencing population distribution in order to anticipate future growth and the areas affected by this growth in Atlanta and Fulton County. We believe that the several conclusions which have led to the estimates of growth and the proposed uses of land to accom modate the anticipated growth are sound, and, together, they make a conservative, realistic basis upon which new zoning regulations and land use and major street plans may be made. We submit "Population, Growth and Distribution" as the first report toward the accomplishment of our objectives. -

United States Conference of Mayors

th The 84 Winter Meeting of The United States Conference of Mayors January 20-22, 2016 Washington, DC 1 #USCMwinter16 THE UNITED STATES CONFERENCE OF MAYORS 84th Winter Meeting January 20-22, 2016 Capital Hilton Hotel Washington, DC Draft of January 18, 2016 Unless otherwise noted, all plenary sessions, committee meetings, task force meetings, and social events are open to all mayors and other officially-registered attendees. WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20 Registration 7:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. (Upper Lobby) Orientation for New Mayors and First Time Mayoral Attendees (Continental Breakfast) 8:00 a.m. - 9:00 a.m. (Statler ) The U.S. Conference of Mayors welcomes its new mayors, new members, and first time attendees to this informative session. Connect with fellow mayors and learn how to take full advantage of what the Conference has to offer. Presiding: TOM COCHRAN CEO and Executive Director The United States Conference of Mayors BRIAN C. WAHLER Mayor of Piscataway Chair, Membership Standing Committee 2 #USCMwinter16 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20 (Continued) Membership Standing Committee 9:00 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. (Federal A) Join us for an interactive panel discussion highlighting award-winning best practices and local mayoral priorities. Chair: BRIAN C. WAHLER Mayor of Piscataway Remarks: Mayor’s Business Council BRYAN K. BARNETT Mayor of Rochester Hills Solar Beaverton DENNY DOYLE Mayor of Beaverton City Energy Management Practices SHANE T. BEMIS Mayor of Gresham Council on Metro Economies and the New American City 9:00 a.m. - 10:00 a.m. (South American B) Chair: GREG FISCHER Mayor of Louisville Remarks: U.S.