Father of the Gateway Arch | the Confluence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monument to a to a Dream

Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle Monument 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~37 1 Manifest Destiny 38~63 2 The Spirit of St. Louis To A 64~134 3 On the Riverfront 135~229 4 The Competition 230~293 5 Wunderkind Dream 294~391 6 Post-Competition Blues 392~478 7 Two Weaknesses 479~536 8 Topsy-Turvy 537~582 9 Peripheral Development 583~600 10 Legacy 1 2 Part 1 Corps of Discovery Manifest Destiny 3 4 Thomas Jefferson had a long interest in western expansion and in 1780s met John Ledyard who discussed with him an expedition to the Pacific Northwest. Two years into his presidency, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition through the Louisiana Purchase and beyond; to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition’s goals were: • Explore the Louisiana Purchase; • Establish trade and U.S. sovereignty over the native peoples along the Missouri River; “To find the most direct & • Establish a U.S. claim of “Discovery” to the Pacific Northwest and practicable water communication Oregon Territory by documenting an American presence there before across this continent, for the Europeans could claim the land; purposes of commerce.” • Seek out a “Northwest Passage” Thomas Jefferson,POTUS Jefferson also understood the U.S. would have a better claim of RE: the Lewis and Clark Expedition, ownership to the Pacific Northwest if the expedition gathered scientific a.k.a. the Corps of Discovery data on indigenous animals and plants. The U.S. mint prepared special Expedition (1804–1806). It was the first silver medals (with a portrait of Jefferson) which had a message of transcontinental expedition to the friendship and peace, called Indian Peace Medals or Peace Medals.The Pacific coast undertaken by the United Corps was entrusted to distribute them to the Indian nations they met States. -

Dedication to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

STUDY, LEARN AND LIVE (continued) SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY JESUIT MISSION “WHAT WE DO HERE, WHICH IS ESPECIALLY UNIQUE, IS TO The Mission of Saint Louis University is the pursuit of truth for the greater PROVIDE A COMMUNITY WITHIN THE COMMUNITY FOR OUR glory of God and for the service of humanity. The University seeks excellence in UNDERREPRESENTED MINORITY STUDENTS. THE FEELING OF the fulfillment of its corporate purposes of teaching, research, healthcare and service to the community. It is dedicated to leadership in the continuing quest BELONGING ENHANCES SOCIAL, ACADEMIC AND EMOTIONAL DEDICATION TO for understanding of God’s creation and for the discovery, dissemination and DEVELOPMENT.” – MICHAEL RAILEY, M.D. integration of the values, knowledge and skills required to transform society in the spirit of the Gospels. As a Catholic, Jesuit university, this pursuit is motivated DIVERSITY, EQUITY You’ll love our city! Check out the new sports-anchored entertainment district by the inspiration and values of the Judeo-Christian tradition and is guided by in the heart of downtown Ballpark Village St. Louis! Attend one of the over 150 the spiritual and intellectual ideals of the Society of Jesus. events scheduled each year including concerts, family shows, community events AND INCLUSION and Saint Louis University men’s and women’s Billiken basketball games at the on Saint Louis University celebrating over 200 years in Jesuit education. campus 10,600 seat Chaifetz Arena. Check out the trendiest boutiques and upscale dining establishments in Clayton and the Central West End. If live music is your OFFICE OF DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION thing, Soulard boasts some of the best blues venues in town. -

1 a Premier Class a Office Building in Downtown St. Louis with Rich Amenities and Spectacular Views

800 MARKET STREET | ST. LOUIS, MO 63101 A premier Class A office building in Downtown St. Louis with rich amenities and spectacular views Jones Lang LaSalle Americas, Inc., a licensed real estate broker 1 BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS Bank of America Plaza provides a premium tenant experience with spectacular views of the city. The building's common areas bring people together with convenient and comfortable lobbies and lounges. The tech-equipped conference center provides meeting space for up to 250 people. While boasting amazing views of Citygarden, the fully-staffed fitness center focuses on employee well-being with top-of-the-line equipment, personal training and group classes. » 30-story designated BOMA 360 Performance Building » Beautiful multi-million dollar renovations of atrium, café, common areas and amenities » On-site amenities + Fitness center + Conference center + Retail banking + 24-hour security + Sundry shop + Café (serves breakfast and lunch) » Attached and covered 2,100-car parking garage with reserved spots available » On-site property management » On-site building engineering staff » Unobstructed views of Citygarden, Busch Stadium, Kiener Plaza and the Gateway Arch » Excellent highway access » Lease rates from $20.00 - $22.00 per SF 2 MORE THAN 32,000 SF OF COMMON AREAS AND TENANT AMENITIES fitness center | conference center | on-site café | sundry shop | large tenant lounge 3 LARGE BLOCK OF CONTIGUOUS SPACE 30 29 Bank of America Plaza currently offers up to 72,876 sf of contiguous 28 space across 3 full floors and 1 partial floor. These upper tier floors offer 27 excellent views of downtown St. Louis from every angle - Citygarden, 26 Busch Stadium, the Gateway Arch and Union Station. -

Bus and Motorcoach Drop-Off for Gateway Arch Bus Drop-Off Is Located on Southbound Memorial Drive Behind What Was Previously the Millennium Hotel

Effective Summer 2016 Bus and Motorcoach Drop-Off for Gateway Arch Bus drop-off is located on Southbound Memorial Drive behind what was previously the Millennium Hotel. Allows for accessible path for those visiting the Gateway Arch. Bus drop-off available for a MAXIMUM of 15 minutes. No parking is allowed in this space. Located South of the Gateway Arch on Leonor K. Sullivan Blvd. between Poplar Street Bridge and Chouteau Ave. From Illinois: Poplar Street Bridge Heading WEST on the Poplar Street Bridge, continue on Interstate 64 West. Take exit 40A toward Stadium/Tucker Blvd. Continue straight off the exit (slightly LEFT) onto S. 9th Street. Continue one block north then take the next RIGHT turn on Walnut Street. Continue EAST on Walnut Street then turn RIGHT on Memorial Drive. Bus drop-off inlet will be on the right immediately after turning onto southbound Memorial Drive. From Illinois: MLK Bridge Heading WEST on the Martin Luther King Bridge, make a SLIGHT RIGHT to stay on N 3rd Street. Turn LEFT on Carr Street. Turn LEFT on Broadway. Continue South on Broadway then turn LEFT on Walnut St. Turn RIGHT on Memorial Drive. Bus drop-off inlet will be on the right immediately after turning onto southbound Memorial Drive. From Illinois: Eads Bridge Heading WEST on Eads Bridge, continue straight onto Washington Avenue. Turn left on Broadway. Continue South on Broadway then turn LEFT on Walnut St. Turn RIGHT on Memorial Drive. Bus drop-off inlet will be on the right immediately after turning onto southbound Memorial Drive. From Illinois: Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge Heading WEST on the Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge, take the LEFT exit for N. -

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition BY JENNIFER CLARK The seven-person jury seated around a table in the Old Courthouse with competition advisor George Howe in 1947. The jury met twice to assess designs and decide what the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial would look like. The designs included far more than a memorial structure. A landscaped 90-acre park, various structures, water features, a campfire theater, museum buildings, and restaurants were also part of the designs. (Image: National Park Service, Gateway Arch National Park) 8 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2018 Today it is hard to conceive of any monument Saint Louis Art Museum; Roland A. Wank, the chief that could represent so perfectly St. Louis’ role architect of the Tennessee Valley Authority; William in westward expansion as the Gateway Arch. The W. Wurster, dean of architecture at MIT; and Richard city’s skyline is so defined by the Arch that it J. Neutra, a well-known modernist architect. George seems impossible that any other monument could Howe was present for the jury’s deliberations and stand there. However, when the Jefferson National made comments, but he had no vote. Expansion Memorial (JNEM) was created by LaBeaume created a detailed booklet for the executive order in 1935, no one knew what form competition to illustrate the many driving forces the memorial would take. In 1947, an architectural behind the memorial and the different needs it was competition was held, financed by the Jefferson intended to fulfill. Concerns included adequate National Expansion Memorial Association, parking, the ability of the National Park Service a nonprofit agency responsible for the early to preserve the area as a historic site, and the development of the memorial idea. -

Thank You, George & Melissa Paz Caring for Your Museum

GATEWAY ARCH PARK FOUNDATION CONNECTION www.archpark.org @GatewayArchPark TERF ¯ BLUES AT THE ARCH E SUNRISE YOGA IN S Looking Join us online every As we all look forward T Tuesday at 7 a.m. The fih annual to Blues at the Arch W at the Gateway Arch Winterfest will return 2021, you can still Ahead 11 Park Foundation to Kiener Plaza in 2020 WINTERFESTrelive the great GATEWAY ARCH PARK FOUNDATION Gateway Arch Facebook page. featuring a whimsical moments G of this N Our “Salute to Veterans” tribute is presented by walk-through holiday A O Park Foundation T I Sco Credit Union. For more information, visit the light display. Stay tuned year’s E T W A A D signature events Gateway Arch Park Foundation Facebook page to www.archpark.org event on Y N A U R F O continue. and website. for more information. our website. C H P A R K Caring for Your Museum The Museum at the Gateway Arch receives an update. ICE RINK MARKET IGLOO VILLAGE The Gateway Arch Westward Expansion period of the United States with National Park is a more perspectives from the cultures involved. Visitors can learn how events that took place in downtown St. Louis the 90+ acres of Gateway Arch National Park shaped oasis. Amid the American history. beautifully forested The new Museum was designed to be a hands-on surroundings found experience with many tactile exhibits and, as anticipated, within one of the it requires regular maintenance and repairs. Gateway Arch Park Foundation serves our National few urban national Park in many ways, including funding ongoing exhibit parks west of the maintenance. -

Our Facilities Meetings and Events Our Rooms Eat and Drink out and About

T: +1 314 421 1776 E: [email protected] OUR ROOMS EAT AND DRINK GUEST ROOMS LOBBY BAR Our standard guest rooms are a field of sweet dreams thanks to the Hilton Serenity Bed Meet your friends or just people watch in Collection™. All rooms also feature high speed internet access and spectacular views of the Lobby Bar and savor a cocktail, beer or the city, Busch Stadium, and the Gateway Arch. glass of wine along with a selection of sandwiches, salads or soups. ACCESSIBLE ROOMS Appointed like our standard guest rooms, our accessible rooms also feature options such MARKET STREET BISTRO AND BAR as roll-in shower or low tub with grab bars and wide doorways. Enjoy American-style breakfast, lunch or dinner prepared with fresh seasonal EXECUTIVE LEVEL Guests staying in our fully appointed Executive Level rooms enjoy breakfast and evening ingredients and accented with views of appetizers in our Evecutive Level Lounge. downtown St. Louis. THREE SIXTY ROOFTOP BAR SUITES With separate living and sleeping areas, our suites are perfect for families or guests Perched on the 26th Floor, our rooftop bar preferring more space or for hospitality suites. Watch the game at Busch Stadium from with seating indoors and out oers soaring the two-bedroom Presidential Suite. views of the St. Louis skyline, the Gateway Arch and an easy base inside Busch Stadium. OUR FACILITIES HILTON FITNESS BY PRECOR © Full equipped with the latest generation cardio and strength training machines, Hilton Fitness by Precor© takes a personalized approach that provides the idea balance to demanding daily lives. -

STLRS Fact Sheet

HYATT REGENCY ST. LOUIS AT THE ARCH 315 Chestnut Street St. Louis, Missouri 63102, USA T +1 314 655 1234 F +1 314 241 9839 stlouisarch.regency.hyatt.com ACCOMMODATIONS RESTAURANTS & BARS 910 guestrooms, including 62 suites / parlors, 388 kings, • Red Kitchen & Bar: daily breakfast buffet, seasonal menu and and 442 double / doubles creative cocktail concoctions All Accommodations Offer • Starbucks®: full service one-stop coffee shop; conveniently located • Free Wi-Fi is available in guestrooms and social spaces like lobbies on the lobby level and restaurants, excluding meeting spaces • Brewhouse Historical Sports Bar: a huge selection of local craft beers, • Hyatt Grand Bed® in-house smoked meats and BBQ • Spectacular Gateway Arch or Downtown view rooms • Ruth’s Chris Steak House: fine dining; famous sizzling steaks, seafood • 50-inch flat-screen television with remote control, in-room pay movies and signature cocktails • Video checkout RECREATIONAL FACILITIES • Telephone with voicemail and data port • StayFit™ Center featuring the latest equipment such as Life Fitness® cardio • Deluxe bath amenities and hair dryer and strength-training machines complete with flat-screen televisions • Coffeemaker • In-room refrigerator MEETING & EVENT SPACE • Iron / ironing board • A total of 83,000 square feet of indoor / outdoor stacked meeting • iHome® alarm clock radio and event space • Dog friendly • Grand Ballroom offers 19,758 square feet of space with 14,600 square feet of prefunction space SERVICES & FACILITIES • Regency Ballroom offers 16,800 -

Mississippi – Louisiana Rhythms of the River

RHYTHMS OF THE RIVER ILLINOIS – MINNESOTA – WISCONSIN – IOWA MISSOURI – TENNESSEE – MISSISSIPPI – LOUISIANA RHYTHMS OF THE RIVER START OPTION 1 Chicago to Springfield, Illinois 3 hours and 11 minutes / 325km Springfield, Illinois to St. Louis, Missouri 1 hour and 30 minutes / 155km START OPTION 2 Minneapolis & Bloomington, Minnesota to Dubuque, Iowa 4 hours and 39 minutes / 406km Dubuque, Iowa to Hannibal, Missouri 3 hours and 48 minutes / 392km Hannibal, Missouri to St. Louis, Missouri 1 hour and 54 minutes / 188km CONTINUING FROM ST. LOUIS St. Louis, Missouri to Nashville, Tennessee 4 hours and 35 minutes / 497km Nashville to Memphis, Tennessee 3 hours and 12 minutes / 341km Memphis, Tennessee to Cleveland, Mississippi 2 hours and 1 minute / 185km Cleveland to Natchez, Mississippi 3 hours and 13 minutes / 290km Natchez, Mississippi to New Orleans, Louisiana 2 hours and 50 minutes / 283km The Cloud Gate at Millennium Park Option 1: Start your trip in Chicago, Illinois BEGIN IN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Start with a visit to some of Chicago’s iconic attractions such as the every night of the week. In Chicago, you’ll be able to choose from Cloud Gate sculpture (a.k.a The Bean) at Millennium Park, the more than 200 live music venues and clubs – with everything from Ledge glass balcony at Skydeck Chicago off the 103rd floor of Willis intimate musical experiences to major concert venues and historic Tower, and the new Centennial Wheel at Navy Pier. Interactive, music halls. Enjoy a deep-dish pizza at Gino’s East or Lou Malnati’s, educational museums abound in Chicago, from The Field Museum or enjoy a Chicago hot dog at locations throughout the city. -

Group Tour St

Group Tour St. Louis Convention & Visitors Commission 701 Convention Plaza, Suite 300 St. Louis, MO 63101 www.explorestlouis.com/groups-reunions [email protected] GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 15 WHAT’S INSIDE 1 WELCOME 2 WEATHER INFORMATION – FOUR SEASONS OF ST. LOUIS 3 GROUP TOUR SERVICES 5 TRANSPORTATION INFORMATION Airport Motorcoach Parking – Policies Car Rental Metro & Trolley 7 MAPS Central Corridor Metro Forest Park Downtown 31 33 36 15 FUN FACTS – (Escort Notes) 17 ATTRACTIONS 31 SIGHTSEEING 33 TECHNICAL TOURS 35 PARADES 36 ANNUAL EVENTS 37 SAMPLE ITINERARIES welcome St. Louis is a place where history and imagination collide, and the result is a Midwestern destination like no other. In addition to a revitalized downtown, a vibrant, new hospitality district continues to grow in downtown St. Louis. More than $5 billion worth of development has been invested in the region, and more exciting projects are currently underway. The Gateway to the West offers exceptional music, arts and cultural options, as well as such renowned – and free – attractions as the Saint Louis Art Museum, Zoo, and Science Center, the Missouri History Museum, Citygarden, Grant’s Farm, Laumeier Sculpture Park, and the Anheuser-Busch brewery tours. Plus, St. Louis is easy to get to and even easier to get around in. St. Louis is within approximately 500 miles of one-third of the U.S. population and within 1,500 miles of 90 percent of the people in North America. Each and every new year brings exciting additions to the St. Louis scene–improved attractions, expanded attractions, and new attractions. Must See Attractions There’s so much to see and do in St. -

History – 1960 Thru 1979

This Time in History NOTABLE EVENTS IN WORLD/U.S. HISTORY - CONTINUED 1968 Martin Luther King assassinated on April 4th 1960 – 1979 1966 Miranda Rights established; Department of Transportation created IMMANUEL MILESTONES Robert F. Kennedy presidential candidate assassinated on June 6th German services were conducted on the first and third Sundays of the month until 1965 when 1969 Neil Armstrong & Buzz Aldrin were the first men to walk on moon (Apollo 11) the German services were discontinued. Woodstock Festival - attended by more the 450,000,held in Bethel, NY 1960 Stained windows installed in church My Lai massacre 1963 Dedication of school: the lower grade school building moved to the present site 1970 Kent State shootings; first Earth Day observed; Apollo 13 mission Built an addition for second classroom, entire building housed grades 1-8 Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) signed into law Church alter carpeted 1971 26th Amendment lowered the voting age to 18 1964 Church centennial celebration 1972 Watergate Scandal 1972 Church carpeted 1973 U.S. ends its involvement in the Vietnam War 1974 Fourth Parsonage built Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned 1977 Final payment on parsonage Oil Crisis - gasoline prices skyrocketed (ended in 1974); Sears Tower completed Many sons of the congregation served in the Viet Nam war, all returned safely except Lyle 1974 President Richard Nixon resigned Mackedanz who became MIA in 1968. 1975 Construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System began; Fall of Saigon Pastors 1976 United States Bicentennial -

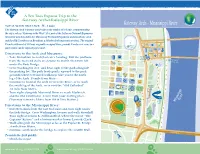

Gateway Arch

A Ten Toes Express Trip to the Gateway Arch-Mississippi River TOTAL WALK DISTANCE: .75 - 3 miles Gateway Arch - Mississippi River The Gateway Arch is known world-wide as the symbol of St Louis, commemorating the city’s role as ”Gateway to the West”. It is part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial which includes the Museum of Westward Expansion underneath the Arch e Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Bridg and the Old Courthouse at Broadway & Market (both museums are free). The original Laclede's Landing Blvd. P ey French settlement of St Louis originally occupied these grounds. Lovely river views in a Edward ll America’s A Jones . Morgan Street St Center cial park setting can be enjoyed year-round. er . Convention Plaza. P th 2nd 2nd th r Comm 7th St No N. Lucas Street Directions to the Arch and Museums: Lucas Ave. Laclede's P P • Take MetroLink to Arch/Laclede’s Landing. Exit the platform Landing Eads Bridge Washington Ave. Wasing MetroLink The Captains’ to y n Ave. Station from the west end stairs or elevator to 2nd St. then turn left wa Return Stat h ue ad rc o A y g Br P in wa k under the Eads Bridge. e N. at ar Locust St. G P • Cross Washington Ave. and bear right to the path alongside 6th St N. the parking lot. The path leads gently upward to the park Olive St. 4th St grounds where tree-lined walkways take you to the north N. Pine St. leg of the Arch .35 mile from Metro.